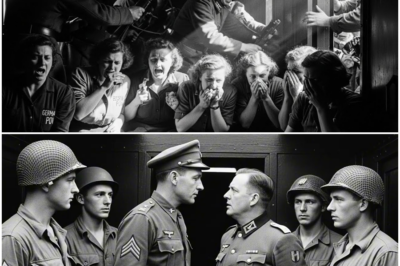

When German POW Generals First Stepped Off The Train And Saw American Small-Town Cafés, Black GIs In Uniform And Supermarkets Overflowing With Food, Their Secret Reactions To The Country They’d Been Taught To Despise Left Their American Interrogators Stunned Silent

By the time the ship nosed into New York Harbor through the gray morning haze, General Heinrich von Falk had already decided what America would look like.

The propaganda back home had been very clear.

America was chaos.

A land of gangsters and cowboys.

Factories drowning in greed.

Streets ruled by money and noise.

He expected crude bigness, not beauty.

He expected vulgarity, not order.

He did not expect the quiet.

From the transport ship’s deck, ringed with guards, he saw it first in the water.

Harbor tugboats moved in precise patterns. No frantic circling, no collisions. The cranes along the docks rose like tall skeletal trees, moving containers with surprising grace.

Behind them, the skyline rose in layers—modern towers, older brick buildings, church spires, all stacked together in a way that felt strangely… deliberate.

He’d seen cities from above before. From aircraft. Through bombsights.

This was different.

This time, he had no illusion of control.

He was a prisoner.

So were the other generals standing with him under the watchful eyes of American guards.

Some clung to their dignity like a uniform they didn’t have anymore—backs straight, hands clasped behind them, faces carefully blank. Others stared openly, unable to hide their curiosity.

“Look at the bridges,” murmured General Krüger under his breath in German, unable to stop himself. “So many. All intact.”

Von Falk followed his gaze.

The bridges were long, spanning water he knew was wider than the rivers he’d grown up beside. Trucks moved steadily across, uninterrupted. No bomb craters. No twisted metal.

No ruins.

His own country’s cities, last he’d seen them, had burned.

Here, everything looked… untouched.

“Gentlemen,” said the American officer escorting them, glancing from one lined face to another. “Welcome to the United States.”

He might as well have said, Welcome to the test you didn’t know you were taking.

Because for the first time—quietly, stubbornly—Heinrich von Falk began to suspect that the war hadn’t told him the whole truth about this place.

From “Victors’ Ship” To “Cattle Car”

The journey across the ocean had been miserable.

They’d been loaded onto the ship in a cold drizzle, herded up gangplanks under shouted orders. Their luggage—what little they’d been allowed—had been searched and sorted. Their names had been checked and rechecked against lists.

“Generals, over here,” the guard had said in accented German, separating them from the line of enlisted prisoners.

He’d expected harshness.

Instead, he’d been mostly ignored.

A guard pointed to a section of deck where cots had been set up under a canvas roof.

“You sleep there,” the guard had said. “Food at 0800 and 1800. Latrines down the stairs. No trouble, no problems.”

“You call this treatment for officers?” Krüger had fumed later. “We are not… cattle.”

Von Falk had said nothing.

He’d remembered railcars jammed with men he had never seen again.

Compared to that, this was almost… comfortable.

The food wasn’t plentiful.

But it arrived.

Bread that was not yet stale.

Soup that was thin, but hot.

Coffee that tasted like burned bitterness—but was coffee nonetheless.

He watched the American sailors move around them.

They didn’t jeer.

They didn’t spit.

They were wary, yes.

But they also seemed oddly… bored.

As if transporting captured generals across an ocean was just one more task on a long, practical list.

The ship’s loudspeakers sometimes played music.

Not the martial pieces he was used to.

Jazz.

Crooning voices.

Songs about faraway lovers and places he’d never heard of.

He listened because there was nothing else to do.

He thought of his own sons, both teenagers, who had probably heard similar songs in secret.

He wondered, not for the first time, what it meant to fight a land whose voices sounded like that.

After days of gray water and colder wind, the sudden appearance of land jolted everyone.

Officers stood up straighter.

Prisoners lined the rails.

The harbor came into view—and with it, something none of them had expected.

Color.

The flags along the dock snapped in the wind.

Trucks in fresh paint stood in neat rows.

Civilians—dockworkers, office clerks, women in coats and scarves—moved along streets in a rhythm that felt… normal.

Not the hollow, desperate trudge of a city under siege.

Normal.

It was, in its way, more shocking than rubble.

“Perhaps this is just for show,” Krüger whispered. “The first port. They want to impress us.”

“Perhaps,” von Falk replied.

He wasn’t sure who he was trying to convince.

The Train Ride That Undid A Story

They didn’t stay in the port city.

Barely had their boots touched American soil before they were marched—under guard but without being shoved—toward a line of railway cars.

Cattle cars, von Falk thought bitterly.

Then he looked again.

Passenger cars.

Benches.

Windows.

“On,” the American sergeant said. “Keep moving. No pushing.”

The generals were ushered into one compartment.

Other officers into others.

The enlisted prisoners into separate cars.

Von Falk sat by the window.

He watched as the port city slid away.

Electric streetcars rattled along tracks.

Children in coats chased each other across a small park.

He saw a man in a suit stop at a street kiosk, hand over coins, and walk away with a newspaper folded under his arm—like an illustration from a life he’d once thought of as normal.

The train moved steadily.

Within an hour, the scenery changed.

Factories rose, chimneys smoking steadily, but without the frantic repair crews and bomb damage he’d come to expect as a backdrop.

Then came suburbs.

Rows of small houses with tidy front yards.

Wash lines.

A bicycle leaning against a porch.

“Look,” murmured one of the older generals. “They have… everything.”

Von Falk thought of the ration lines back home.

Of the cities where house fronts were just facades now.

Of the letter from his wife, months ago, saying they had moved into a cousin’s apartment after their building was hit.

He shook the image away.

He had to live in the present now.

This present felt indecently intact.

Further inland, the trip grew stranger.

He had never truly understood how vast America was.

Hours passed.

Fields.

Rivers.

Small towns with names he couldn’t pronounce.

Water towers painted with cheerful slogans.

Each one seemed to say, “We are untouched. We are fine.”

At one station, as the train slowed, he saw something that made him sit up straighter.

A group of soldiers on the platform.

American.

Black.

Their uniforms were the same color and cut as the white soldiers’ around them.

Their insignia.

Their boots.

Their rifles.

Everything matched.

Von Falk had heard stories—snippets from foreign radio, whispered rumors—that America had its own deep divides.

None of that prepared him for the sight of a Black sergeant casually flipping through a magazine while a white private adjusted a pack nearby.

The two spoke briefly.

Equal.

No one else on the platform seemed surprised.

“You see that?” Krüger hissed quietly, shifting on his bench. “They arm them.”

Von Falk watched the Black soldiers laugh at some shared joke, one of them tossing a packet of cigarettes to another.

“It appears they do,” he said.

Something in his carefully constructed picture of “how the world works” cracked.

If the propaganda had been wrong about that—

What else had it been wrong about?

Arrival At The Camp

They arrived at their destination after dark.

They couldn’t see much of the landscape when the train finally squealed to a stop.

Only the outline of low buildings and a fence.

Same wire.

Different sky.

“Out,” the guard ordered. “One at a time.”

They climbed down.

The air was cooler here.

Smelled of pine and dust.

As their eyes adjusted, they saw the sign above the gate.

CAMP ASHFORD.

The name meant nothing to them.

Inside, a colonel in a neatly pressed uniform waited.

He had an interpreter at his side.

“Gentlemen,” the colonel said. “You will be processed tonight and assigned quarters. This is not a punishment camp. You have responsibilities under international conventions. We do too. If you follow the rules, your time here will not be… unpleasant.”

The interpreter relayed the words in clear German.

Krüger snorted softly.

“American hospitality,” he muttered.

Von Falk didn’t reply.

He was watching the nurses.

Two of them stood near the gate.

White armbands with red crosses.

They were scanning the faces of the arriving prisoners with a practised eye.

Noting limps.

Pale skin.

Coughs.

One of them—dark hair tucked neatly under her cap—stepped forward when an older general stumbled.

“Easy,” she said to the guard. “He’s not a sack of flour. Let him sit a moment. We’ll check him.”

The guard nodded, actually nodded, and steered the older man toward the medical hut instead of shoving him.

Kindness, von Falk thought, can be more disorienting than cruelty.

He’d prepared himself to be hardened. To endure.

He had not prepared for being treated like a human being by people he had been told were “degenerate.”

It left him nowhere to put his anger.

Nowhere to hang his shame.

The Laundry Room Reveal

It wasn’t just the soldiers and nurses that shocked the generals.

It was the details.

The next day, after a bland but filling breakfast (porridge, bread, coffee—real coffee), von Falk was allowed, with two others, to see the section of the camp where their uniforms would be laundered.

An American logistics officer walked them through the “facilities” as if giving a tour of a factory.

It was, in its own way, impressive.

Rows of washing machines.

Drying lines inside a heated building.

Organized bins.

“You’ll send your clothes once a week,” the officer said through the interpreter. “You will receive a ticket. You will get your same clothes back. We will repair what we can.”

“One could eat off this floor,” Krüger muttered in German, half-sarcastically, as they walked through.

One of the American laundry women glanced at them.

“We try,” she said in English, catching the tone even if not the words.

Later, when the generals were back in their barracks, one of them—General Meyer, who had commanded an entire division—sat on his bunk, staring at the clean shirt in his hands.

“They wash our clothes,” he said quietly. “They have machines just for this. Back home, my wife queues for hours at a pump. And here, the enemy is washing my shirt.”

He sounded less impressed than… bewildered.

“What did you expect?” von Falk asked before he could stop himself. “A cage and cold bread?”

Meyer looked up.

“I expected to see a country stretched to breaking,” he said. “Like ours. I expected ration lines, bomb scars, worry. Instead, I see order. Plenty. And women who smile while washing uniforms of men who tried to break them.”

The Library And The Farm

The shocks kept coming.

The camp had a library.

Not large.

But real.

Books donated by local organizations.

Some in English.

Some in German.

“If you want to read,” the monotone interpreter had said during orientation, “you may request a pass. No political materials. No maps. Novels, mostly.”

“Novels,” Krüger had scoffed later. “We are supposed to pass the time with stories while the world rebuilds without us.”

Von Falk had picked up a battered copy of “Moby-Dick” the first week.

Partly out of curiosity.

Partly because he had more time now than he’d had in years.

The camp also had a small farm project.

“Agricultural work,” the American captain explained. “Voluntary. You get fresh vegetables. We get help. The war will end with hunger here too if we don’t plan ahead.”

Watching generals who’d once commanded thousands of men bend over bean rows was a quiet humiliation.

It was also… grounding.

Within weeks, some of them began to take pride in the straightness of their furrows.

“Look at this,” one said, holding up a carrot. “We are very nearly peasants again.”

The Americans didn’t mock.

They worked alongside them sometimes, sweating under the same sun.

At lunch, they ate similar food.

Same bread.

Same soup.

The main difference was who had the guns afterward.

It was not equality.

But it was a kind of shared reality.

And that unsettled the generals more than open hostility would have.

“I was told they were soft,” Krüger muttered one day, watching a group of American guards play baseball with a ball and bat cobbled from camp materials. “That they lacked discipline. That they were lazy.”

“Soft men don’t run supply lines like this,” Meyer replied quietly, nodding toward the well-stocked camp stores. “Soft men don’t feed their prisoners this well while sending food to Europe.”

Von Falk said nothing.

He was thinking about the train again.

The bridges.

The lack of ruins.

The obvious wealth.

He was also thinking about the library.

About a conversation he’d had with one of the American nurses in a rare moment of shared language.

The Nurse’s Question

His English was good enough.

Her German was not.

They met somewhere in the middle.

“You were… university?” she asked one day, glancing at the book in his hands as he sat waiting for a blood pressure check.

“Yes,” he said. “History. Before.”

“History,” she repeated. “Now you… live history.”

He gave a humorless smile.

“Not the way I imagined,” he said.

She nodded.

“Me too,” she replied. “I read about wars in school. It was… dates. Lines on a map. Now I see… bodies. Minds. It is very different.”

He hesitated.

“You chose this,” he said. “Nursing.”

“Yes,” she said simply.

“Even for… us?” he asked, nodding at the rows of cots.

She didn’t flinch.

“I chose to be a nurse,” she said. “Not… a judge. There are people whose job is to decide why you are here, what you did, what happens to you. That is not mine. My job is to see if you have fever and if your cough needs medicine.”

He studied her face.

“So you feel nothing?” he asked. “No anger? No… contempt?”

She paused.

“I feel many things,” she admitted. “Anger. Sadness. Especially when I read reports from Europe. When I see pictures. When I think of families here who lost sons because of decisions made by men with stars on their shoulders.”

His shoulders.

She continued.

“But I also feel something else when I listen to prisoners talk about their families,” she said. “A strange… sameness. Worry sounds similar in every language.”

He looked down at his hands.

“Does that make you… forgive us?” he asked.

She shook her head.

“Forgive is a big word,” she said. “Bigger than this hut. Bigger than me. I don’t know if I can carry it. But I can carry a tray. And I can decide that today, when you say your tooth hurts, I give you something for it. That is already… something.”

Forgive was indeed a big word.

Too big for him to hold then.

But he carried her smaller one with him.

“Same.”

Sameness.

Under the uniforms.

Letters Home

The first letters from America were hard to write.

“Where are you?” his wife asked in her last letter from a corner of bombed-out Germany.

“In a camp,” he wrote back.

“Is it terrible?” she asked.

He hesitated.

How to explain that it was both better and worse than he’d expected?

That he had enough to eat while she rationed?

That he slept in a clean bunk while she might be sleeping in rubble?

That he saw intact buildings every day while she saw smoking ruins?

He wrote:

“We are being treated according to conventions. There is enough food. Some work. Some reading. It is… organized.”

He did not write:

“I have seen supermarkets with more abundance in a single aisle than our village saw in a year.”

Because yes—one day, under escort, they had driven past an actual American supermarket.

It had happened when they were transferred to a different camp.

The truck had taken them along a main road in a small Midwestern town.

He’d seen it from the back of the vehicle—a big front window, rows of shelves visible through the glass.

Canned goods stacked neatly.

Signs advertising sales on things he hadn’t seen in months: sugar, coffee, fruit.

Women pushing carts.

Laughing.

“No rubble,” Krüger had said flatly.

“No rubble,” von Falk had echoed.

He also did not write:

“I have seen Black soldiers in uniform with lieutenant’s bars, walking beside white officers as equals. This is not the America we were taught.”

Nor:

“I am beginning to suspect we were lied to.”

Those thoughts stayed between the barracks boards and his insufficient sleep.

Quiet Shock, Loud Silence

One afternoon, months into their captivity, a senior American intelligence officer visited the camp.

He wanted to speak to the generals.

Not for interrogation.

Not officially.

Curiosity.

He sat with them in the camp’s small mess hall, an interpreter at his side.

“How do you find our country?” he asked.

There was a long pause.

Directness, von Falk thought. That is also something.

Krüger cleared his throat.

“It is… different from what we were told,” he said carefully.

“In what way?” the officer pressed.

“No ruins,” Meyer said bluntly.

The officer’s mouth twitched.

“We were luckier,” he said.

“Luck is not enough to build all of this,” von Falk interjected quietly. “The roads. The factories. The towns. The food in the shops. This took time. Planning. Will.”

The officer shrugged.

“Geography helps,” he said. “We have distance. You did not.”

“And yet,” von Falk said, “we were told you were soft. Disorganized. Your citizens decadent. Your government corrupt. Your army… improvising.”

He thought of the bridge from the train.

The laundry.

The library.

The farm project.

“If improvisation looks like this,” he said, “I misjudged badly.”

The officer studied him.

“Does that make you… angry?” he asked. “To realize your enemy was not what you thought, and your country’s calculations were off?”

Von Falk considered.

“In war,” he said slowly, “we train ourselves to simplify. To say, ‘They are this, we are that.’ It makes decisions easier. It also makes mistakes larger. Seeing your country now… yes. It makes me angry. Not at you. At what we were not told. And at what we did, thinking the world looked different than it does.”

There was a small silence.

The interpreter shifted.

The officer nodded.

“That’s more honesty than I expected,” he said.

“I have less to lose now,” von Falk replied. “The uniforms are gone. The myths can go too.”

After The Wire

When von Falk finally returned to Germany, it was to a land that looked more like the war photographs than the memories in his head.

Ruins.

Rubble.

Lines.

He’d lost weight, but not as much as people here.

His wife, thinner, older, hugged him and cried.

In the evenings, when the children were asleep, she asked him about America.

“Is it true?” she said. “Everything they say? Cars for everyone? Bananas in the shops?”

He thought of the supermarket.

Of the Black lieutenant.

Of the nurse in the camp choosing careful words over easy hatred.

“Yes,” he said. “And no.”

She frowned.

“What does that mean?” she asked.

“It means,” he said slowly, searching for words, “that they are neither devils nor angels. They are… people, like us. With more space. More resources. Different faults. But their strength is real. Their industry, their logistics, their way of organizing… if we do not understand that, we will learn nothing.”

“Do you… hate them?” she asked quietly.

He thought of the guard sharing a cigarette outside the hut one snowy night.

Of the nurse arguing with her superior over vitamins.

Of the library’s worn books.

“I don’t have the energy to hate abstractions anymore,” he said. “I have enough to rebuild a house. Maybe a street. That’s it.”

She nodded.

They never talked about ideology again.

They talked about bricks.

Bread.

Schooling for their children.

Years later, when a granddaughter asked him, “Opa, what was America like, when you first saw it?” he’d answer,

“Too clean. Too intact. Too different from everything I’d been told to expect. And yet… it was also strangely familiar. People worked, worried, laughed. They washed clothes. They planted gardens. The biggest shock was not that they were powerful. It was realizing how normal they were.”

She’d frown, disappointed by the lack of drama.

“No cowboys?” she’d ask.

“Only in the films they eventually sent us,” he’d reply, smiling. “In real life, it was warehouses and laundries and nurses with stern faces and kind hands.”

What Shock Really Looked Like

The headline version of their story is simple and dramatic:

German POW Generals were shocked by their first sight of America.

But shock, in their case, wasn’t one moment of theatrical astonishment.

It was a slow accumulation of dissonances.

A harbor without ruins.

Bridges still standing.

Supermarkets with full shelves.

Black soldiers in command roles.

Nurses treating them with dignity instead of contempt.

Laundry done in machines instead of rivers.

Libraries in POW camps.

Guards who sometimes looked them in the eye and saw men, not monsters—or perhaps both.

Each small, unexpected thing chipped away at a worldview built on loud slogans and simplified enemies.

By the time they went home, most of them were not “converted” to any new creed.

They were, in many cases, quieter.

Less sure that the world could be easily sorted into categories.

More aware that their country’s myths had left out crucial details about the strength of the people they’d chosen to fight.

That might not be as satisfying as a dramatic conversion or an immediate renunciation of everything they’d believed.

But it was real.

And in a way, it was more dangerous to any future conflict than any single confession would have been.

Because it meant that behind the stories of flags and glory, there were men sitting in small German apartments, telling their grandchildren:

“Be careful when someone tells you that another country is weak, stupid, corrupt, or soft. I’ve seen one of those ‘soft’ countries up close. Its nurses were firm. Its docks were efficient. Its bridges were still standing when ours fell. Don’t underestimate what you don’t know.”

Shock, in other words, turned into memory.

And memory, passed quietly over kitchen tables, outlasted the wire at Camp Ashford.

The German generals had lost their battle.

They had lost their war.

But in losing, they had been forced to see a version of their enemy that was more complicated, more human, and more capable than the caricature they’d been handed.

And that, perhaps more than any interrogation or intelligence report, was the real intelligence they carried home:

A story about a country they’d once sworn to defeat—

and about the people in that country

who, when handed power over defeated adversaries,

chose discipline over arrogance,

and surprisingly often,

kindness over revenge.

News

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned on Them—and How Shocked U.S. Soldiers Intervened in a Mysterious Incident That Led to Three Sudden and Unexplained Dismissals”

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned…

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced U.S. Soldiers Returning Their Missing Children in a Mysterious Encounter That Transformed Fear Into an Unbelievable Wartime Revelation”

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced…

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII Camp and Left German POWs Whispering About a Night They Could Never Explain or Forget”

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII…

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before Their Wounds Worsened — Until American Soldiers Discovered the Hidden Scene Moments Before a Quiet Infection Threatened to Change Their Fate Forever”

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before…

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove Her — Until American Soldiers Intervened in a Stunning Rescue That Uncovered a Hidden Plot and a Wartime Mystery Buried for Decades”

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove…

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone in the Middle of the Night—But What Happened After I Walked Away Revealed a Hidden Secret That Completely Transformed Our Family’s Story Forever”

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone…

End of content

No more pages to load