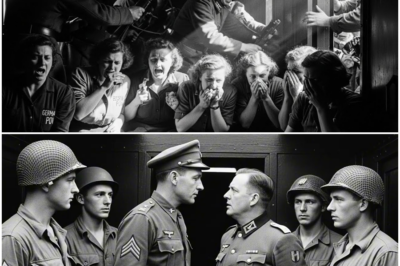

When German Child Prisoners First Tasted British Ice Cream Outside The Barbed Wire, Their Trembling Smiles And Shocked Tears Made Grown Soldiers Drop Their Tough Masks And Realize The Enemy’s Children Were No Different From The Ones Waiting Back Home

If you had asked Corporal James Carter, sometime in the winter of 1944, what might finally make him cry in uniform, he’d have given the obvious answers.

A letter with a black edge.

News of a friend gone.

Another village reduced to bricks and dust.

He wouldn’t have said “ice cream.”

And he certainly wouldn’t have said “German children eating it.”

Yet that, in the soft English summer of 1945, was the moment that knocked the breath out of him in a way no artillery ever had.

Not a battle.

Not an explosion.

Just a row of thin, wary children staring at something cold and sweet in their hands as if it might vanish if they moved too fast.

And then it was James, the tough sergeant, the veteran of beach landings and long marches, who turned away and blinked hard, hoping no one noticed.

Of course they noticed.

The whole camp noticed.

Because by then, nobody in Camp Harbury could pretend that the war had only been about maps and flags and words shouted in big rooms.

It had also been about these faces.

And what to do with them now that the guns were quiet.

The Camp Nobody Had Imagined

Camp Harbury wasn’t on any postcard.

It sat on a stretch of scrubby land a few miles inland from the southern English coast, ringed with wire and watchtowers that already looked slightly out of place under the gentle August sky.

It had been built quickly in 1944, when the army realized it needed more places to put the growing number of captured enemy personnel.

By the time the war in Europe had officially ended, the camp had changed.

The big influx of adult prisoners had slowed.

Instead, Harbury started receiving a different kind of transport.

Families.

Women and children from interned ships.

Teenagers picked up with retreating units.

Younger boys who had followed older brothers west and ended up in the same surrender pile.

They weren’t exactly “prisoners of war” in the classic sense.

But they were not yet civilians either.

Their papers were a mess.

Their homes—if they still had them—were somewhere across the sea, in a country now trying to figure out how to be something other than what it had been for twelve years.

So the British did what they often did in confusing situations.

They improvised.

“Temporary accommodation,” the orders said.

“Separate the adults from the children as little as possible.”

“Basic education and care to be provided when feasible.”

“Feasible” turned out to be a small miracle held together by overworked officers, tired nurses, and stubborn local volunteers.

A school hut went up near the back of the camp.

A patch of hard earth became a football pitch.

A part of the camp that had once held stern, uniformed men now had walls decorated with clumsy drawings in colored chalk and the sound of laughter mixed with sudden, sharp silences.

Because these were not ordinary schoolchildren.

They had learned to flinch at sudden noises.

They had learned not to ask for seconds.

They had learned, very quickly, that adults in unfamiliar uniforms might be angry, indifferent, or occasionally kind—but that guessing which was which was dangerous.

The British soldiers at Harbury had learned just as quickly that these “internees” were not the enemy they’d trained to fight.

When a three-year-old bursts into tears because a boot scraping on gravel sounds too much like something else, it is hard to feel triumphant.

When a ten-year-old swallows his food so fast he chokes because he expects the plate to be taken away, it is hard to stay comfortably distant.

The war in Europe was over.

The work of unlearning had only just begun.

The Sergeant And The Schoolteacher

James Carter had been in uniform since 1940.

He’d come ashore in Normandy, slogged through hedge-lined lanes and ruined towns, and watched friends vanish in flashes of earth and metal.

By 1945, the army had decided he’d earned a posting that involved more fences than shells.

“Harbury,” his commanding officer said. “Guard duty. Maintenance. Some overseeing of… other matters.”

“Other matters” turned out to be people like Greta.

She was twelve.

Thin.

Dark-haired.

She wore the same dress almost every day, washed and re-washed until the seams frayed.

The first week she’d arrived, she’d tried very hard not to be noticed.

James noticed.

Not because he was particularly sentimental.

Because he’d seen that look before.

On the faces of children in bombed-out French villages.

On the faces of his younger cousins during the Blitz.

The look of someone who had seen too much, too fast, and was now trying to be invisible in case the world decided to throw another catastrophe at them.

The camp schoolteacher noticed too.

Her name was Nora Bennett.

Before the war, she’d taught in a village school where the biggest problem had been boys throwing ink at each other.

During the war, she’d volunteered for civil defense and grown used to shepherding frightened children into shelters in the middle of the night.

When the war ended, she’d thought she might be able to go back to spelling tests and local harvest festivals.

Then the notice came from the Home Office.

“Temporary teacher needed for internment camp with German children. Patience essential.”

She’d gone.

Because, as she told her brother, who thought she was mad,

“These children didn’t choose anything. They just had the bad luck to be born in the wrong place at the wrong time. Someone has to talk to them about something other than rations and re-education.”

Greta ended up in her class.

Quiet at first.

Then, slowly, less so.

One afternoon in July, as the heat pressed down and the air tasted of dust, Nora wrote the English words for “colors” on the board.

“Red,” she said, tapping the word.

“Rot,” Greta murmured automatically.

“Blue,” Nora said.

“Blau.”

“Green.”

“Grün.”

The girl at the next desk giggled.

“See?” Nora said in English, smiling. “We are not so different. Just a few new sounds.”

Greta tried to smile back.

Then her stomach growled.

Loudly.

Even over the groan of the ceiling fan.

She flushed scarlet.

A few of the boys snickered.

Nora’s smile faded.

“Lessons are over for today,” she said briskly. “Out you go. Fresh air. Off with you.”

The children filed out.

Greta lingered, head down.

When they were alone, Nora walked to the cupboard where she kept supplies.

She pulled out a tin.

Biscuits.

Not many.

Donated by her sister, who’d battered the shopkeeper down to an extra packet “for the poor mites.”

Nora opened the tin and slid it toward Greta.

“Here,” she said. “For studying hard. That stomach of yours will ruin my lessons if it keeps making more noise than I do.”

Greta’s eyes widened.

She looked at the biscuit.

Then at Nora.

Then back at the biscuit.

“Can I… take it to Mama?” she asked in careful English.

“You can eat one and take one,” Nora said. “That’s the rule. Teacher’s orders.”

Greta picked the smallest one.

Broke it in half.

Ate one piece so slowly it barely seemed to crumble.

Wrapped the other in a handkerchief with ritual precision.

“Tanks,” she said, accent heavy.

“Thank you,” Nora corrected gently.

“Tank… you,” Greta tried again.

Nora smiled.

“Good,” she said. “Better.”

The next day, she overheard two of the soldiers joking.

“Those kids can smell sugar from a mile away,” one said. “Look at them, like my lot when the van comes.”

“The van?” Nora asked later in the mess.

“The ice cream van,” James said. “Back home. Summer. You hear that bell? Every kid in the street appears.”

Nora stirred her tea.

“No ice cream here,” she said. “Just watery barley and powdered milk if we’re lucky.”

James’s smile faded.

“Used to think that stuff would be miserable after a war,” he said. “Turns out ‘miserable’ is seeing a twelve-year-old act like half a biscuit is treasure.”

The conversation stayed with him that night.

As did the memory of his youngest brother, Tommy, at home in Birmingham, sticky-faced in the yard after chasing the ice cream man.

He thought of Tommy.

Then he thought of Greta.

Then he looked at the glass of warm beer in his hand and wondered how, in a country that could produce both, it had never occurred to him to connect the two.

The Idea That Should Have Been Obvious

It wasn’t one person’s idea.

Like most good things in messy places, it arose from a jumble of small conversations.

Nora mentioned half biscuits to the camp nurse.

The nurse mentioned it to the captain.

The captain mentioned it to his wife when he went home for a weekend.

His wife mentioned it to a local shopkeeper.

The shopkeeper mentioned it to a relative who ran a small café.

The relative said, “We’ve got an old ice cream churn in the back. Haven’t used it since before the war. Cream’s rationed, but I’ve got connections.”

“Connections” turned out to be two dairy farmers and a women’s organization that had been browbeaten into making something “nice for once” instead of yet another sensible soup.

Within a week, there was a plan.

Nothing official.

Nothing in writing.

Just a flurry of quiet arrangements.

On the British side:

A day selected when the camp stocks were not at their lowest.

A time chosen when no major inspections were scheduled.

A space agreed upon just inside the wire, away from the main gate but visible from the barracks.

On the village side:

Milk collected.

Sugar saved from coupons.

Powdered flavoring scrounged from somewhere.

“It won’t be what we remember,” the café owner said, stirring the churn. “But it will be cold. And vaguely like feed.”

“That’s good enough,” Nora replied.

James, roped in by virtue of being “young enough to lift” and “soft enough to care,” delivered the last crate of ingredients.

He watched the churn spin.

The paddles scraping.

The ice and salt around the container.

He hadn’t realized how much he missed the smell of cream until that moment.

“Feels wrong,” he muttered, half to himself. “Cream. In a camp.”

The café owner, Mrs. Atkins, shoved her curls back with the back of her hand.

“Feels very right to me,” she said. “My son is still in a prisoner camp somewhere out there.” She jerked her head vaguely east. “If anyone ever gives him something cold and sweet, I’ll kneel and thank them from here. This is just me… starting the chain.”

He shut up.

Fair enough.

The Announcement

They didn’t tell the children in advance.

Partly because they didn’t want to raise hopes if something fell through.

Partly because it felt… wrong to make a big fuss.

“We’re not staging a pageant,” the captain said. “We’re just giving them something nice. No speeches.”

So on a bright Saturday afternoon, when the sun was high and the shadows short, Nora ended the impromptu English lesson early.

“We are going outside,” she said in her careful classroom voice. “All of you. Bring your cups. The metal ones.”

“Why?” asked Otto, a skeptical boy who’d developed a habit of questioning everything.

“If I wanted you to critique the plan,” she said dryly, “I’d ask the colonel. Just go.”

The children filed out of the school hut, muttering.

Greta fell into step beside her.

“Are we working?” she asked.

“Is eating work?” Nora countered.

“Yes,” Greta said seriously. “Since we came here, it always feels like work. To chew. To swallow. To say thank you. To hide the plate.”

Nora almost stumbled.

“You do not have to hide the plate here,” she said. “You know that.”

Greta shrugged.

“It is an old habit,” she said.

Nora made a mental note to talk to the therapist about that.

They reached the open yard.

A shape stood near the wire that hadn’t been there before.

A large, barrel-shaped contraption on wheels, painted white with fading letters on the side.

Most of the paint was gone.

But if you squinted, you could still make out what it had once said.

ICE CREAM.

The children froze.

Not because they recognized the words.

Because they recognized the reactions of the guards.

James, standing next to the contraption with a stack of metal scoops, looked almost… excited.

The captain had his arms crossed, trying for stern and landing somewhere near “awkwardly pleased.”

The camp nurse stood nearby with a rag and a bucket, prepared for sticky faces.

And Mrs. Atkins, apron on, hair pinned back, leaned over the churn, checking the consistency.

“What is that?” Otto whispered.

“Snow in a box,” Greta muttered.

“No,” said a boy who’d once been evacuated to the countryside before being sent back and then over here. “It’s better. It’s… ice cream.”

The last two words almost reverent.

“Eis?” someone repeated. “Real?”

“Sort of real,” James said, hearing the German word. “Not perfect. But cold.”

Nora clapped her hands.

“Line up,” she ordered. “Smallest first.”

They obeyed.

Because they’d had practice lining up for everything.

Food.

Roll call.

Inspections.

This line felt different.

Less like sorting.

More like… possibility.

The First Scoop

“Name?” Mrs. Atkins asked the first child.

“Lena,” she said, voice barely audible.

“Age?” Mrs. Atkins continued.

“Six.”

“Six!” Mrs. Atkins said, as if this were the most astonishing thing she’d ever heard. “Well. Six is an important number. It clearly requires a full scoop.”

She dipped the metal spoon into the churn.

Brought it up with a clump of pale, slightly grainy ice cream.

It was not perfect.

It had ice crystals and slightly uneven coloring.

But it held shape.

She nudged it into Lena’s metal cup.

“Careful,” she said. “It bites if you go too fast.”

Lena stared.

The coldness of the metal seeped into her fingers.

She held the cup up, sniffed.

Her eyes widened.

“It smells… sweet,” she whispered in German.

“Of course it does,” Otto grumbled behind her. “It’s what sugar looks like when it’s singing.”

“Go,” Nora said gently, giving Lena’s shoulder a small push. “Sit on the bench. Take small bites. Don’t waste.”

Lena took a step.

Two.

Then, with utmost seriousness, she sat on the edge of the bench.

She lifted the spoon.

Her hand trembled.

She put a tiny bit of ice cream on her tongue.

For a heartbeat, her face was still.

Then her whole expression shifted.

Her eyes went huge.

Her mouth formed a perfect “O.”

She made a sound that was half-gasp, half-sob.

“It’s cold,” she blurted in German. “It’s cold and… and…”

Her voice broke.

Tears spilled down her cheeks.

Everyone nearby froze.

Mrs. Atkins blanched.

“Oh love,” she said. “Did your teeth—did it hurt?”

Lena shook her head furiously, clutching the cup like a lifeline.

“It tastes like… nothing bad,” she said, words stumbling. “Like… like… visiting my aunt before the sirens. Like… like the day the river froze and we licked the icicles. I forgot… I forgot this feeling.”

She started to cry harder.

Not the hysterical wails of a child denied.

The strange, soft crying of someone whose body had remembered something her mind had set aside to survive.

Behind her, the line shifted.

Greta, second in line now, stepped up automatically, metal cup out.

Mrs. Atkins’ hands shook.

James cleared his throat.

“This was a bloody stupid idea,” he muttered to the captain, eyes bright.

The captain swallowed.

“No,” he said quietly. “It was the right one. That’s why it hurts.”

Soldiers Crying Over Ice Cream

By the time they’d served ten children, the yard had changed.

The air was full of small, involuntary sounds.

A sharp intake of breath.

A stifled giggle.

A muttered curse in German when someone bit too hard and gave themselves a “brain freeze” they didn’t have a word for.

“Too cold!” one boy yelped, pressing his hand to his forehead.

“Slow down,” Nora called. “It’s not running away.”

Laugher rippled.

Real laughter.

Tentative, as if the air might shatter.

Greta took her cup to the fence.

She sat on the ground, back against the post, cup in both hands.

She stared at the melting mound for a long time.

“Are you going to eat it?” James called over in English, trying for lightness.

“If I eat, it will be gone,” she replied in German.

He didn’t understand every word.

He understood enough.

“If you don’t eat, it will be gone too,” he said. “Just… in a sadder way. Better to have it inside you.”

It was Nora who translated, half shouting, half laughing.

“That is terrible poetry, Corporal,” she said. “But he’s right.”

Greta hesitated.

Then, very deliberately, she scooped up a small amount.

Put it in her mouth.

Closed her eyes.

When she opened them again, they were wet.

Not sobbing-wet.

Just… bright.

“It tastes like… nothing that happened since the bombs,” she whispered. “I… I feel like before. For a moment.”

The boy next to her, mouth smeared with white, nodded furiously.

“I didn’t think cold could be… good anymore,” he said.

James turned away.

He didn’t want them to see his face.

He walked a few steps, pretended to adjust his bootlace.

The captain joined him.

“Soft, are you?” the captain asked quietly, not unkindly.

“Shut up,” James said, voice rough. “It’s the smoke.”

“There is no smoke,” the captain pointed out.

“Then it’s the bloody sugar,” James muttered.

From the corner of his eye, he saw the camp doctor, a man who’d seen more than his fair share of suffering, flick his hand quickly across his own face.

It wasn’t just the children.

Some of the older detainees watched too.

Women in their forties and fifties.

A man with a cane—too old to be called up, too stubborn to leave his sons—leaned on the fence.

They didn’t get ice cream.

Supplies were limited.

But they watched their children’s faces soften.

Some smiled.

Some turned away, shoulders shaking.

The British soldiers, hardened by years of training and months of combat, stood around the churn and the bench and the fence and pretended they weren’t all suddenly, painfully aware that the word “enemy” had never looked less useful.

Greta’s Question

Later that evening, after the cups had been washed and the churn wheeled away, Greta sat on her bunk with her mother.

“Mama,” she said, fingering the edge of the thin blanket. “Why did they… do that?”

“Do what?” Martha asked, rubbing her ankle.

“Give us that,” Greta said. “The cold… sweet… thing.”

“I believed you forgot the word,” Martha said, half-smiling.

“Eis,” Greta said. “Ice cream. I remember now. But… why? We are… theirs now. They won. They owe us nothing.”

Martha looked at her daughter.

At the shadows under her eyes.

At the faint smear of white near her ear she’d missed when washing.

She thought about answering with the simple things people liked to say.

Because they want to look good.

Because someone told them to.

Because they feel sorry for us.

She shook her head.

“I don’t know,” she said honestly. “Maybe because their children like it. Maybe because they had some milk and thought, ‘Why not?’ Maybe because someone told them we are people as well as prisoners.”

“That’s new,” Greta muttered.

Martha reached out.

Smoothed her daughter’s hair back.

“When I was your age,” she said slowly, “if someone had told me that someday I’d sit behind a fence and eat something sweet made by the hands of those I’d been told were my enemies, I would have called them crazy.”

“Would you have eaten it?” Greta asked.

“Yes,” Martha said. “I was never foolish enough to say no to sugar.”

Greta smiled.

“Do you… trust them now?” she asked softly.

Martha’s hand paused.

“Trust is a staircase,” she said. “Not a door. You climb it step by step. Today was a step. A small one. But it was not down.”

Greta thought about that.

She thought about the white mound in her cup.

About the guards watching, not with malice, but with something like… tenderness.

About the way the nurse had dabbed a drip off a child’s chin with the same care she’d used on a British boy the week before.

“Will there be more?” she asked.

“More ice cream?” Martha asked. “Probably not soon. These times… they don’t have much. Even here.”

“More steps,” Greta clarified.

Martha looked out the small hut window at the yard, now quiet.

“I think so,” she said. “For them. For us. As long as we don’t decide we like the fences more than the steps.”

The British Perspective, Years On

Decades later, in a small house in a quiet English town, an old man sat at his kitchen table, stirring sugar into his tea.

On the wall behind him, a photo hung slightly askew.

It was black and white, slightly blurred.

A group of children sitting on a bench, metal cups in their hands, faces caught between laughter and tears.

Beside them stood two figures in uniform.

One was a young woman in a nurse’s cap.

The other was a very young man in a British army jacket, his expression somewhere between awkward and proud.

“Granddad,” a child’s voice piped up. “Tell the ice cream story again.”

Thomas “Jacko” Jackson smiled.

“You lot never get tired of that one,” he said.

“It’s our favorite,” his granddaughter insisted, climbing onto the chair opposite. “You always cry.”

“I don’t cry,” he protested.

“You wipe your eyes,” she countered. “That’s secret granddad crying.”

He laughed.

“All right,” he said. “Once, a long time ago, after a very bad time the grown-ups called a war, there was a camp…”

He told it simply.

Less about nationalities.

More about children.

More about how strange it had felt to watch kids who had known hunger and fear treat a spoonful of cold sweetness like something sacred.

“How did it make you feel?” his granddaughter asked, as she always did at that point.

He thought about saying the usual.

“Sad.”

“Happy.”

Both true.

But the older he got, the more he felt something more complicated.

“Small,” he said finally.

She frowned.

“Small?” she echoed.

“Yes,” he said. “Small in the best way. Like I realized that all the big words people use—victory, defeat, enemy, ally—are very big coats. And under them, everyone has the same skin that goes goosepimply when it’s cold. And the same eyes that go shiny when they taste something that reminds them of not being afraid.”

She considered that.

“That’s too many words,” she said. “You’re supposed to say ‘happy.’”

He laughed.

“Then put it this way,” he said. “It made me happy and sad at the same time. And it made me hope that somewhere, in some other camp, someone was giving your age’s version of an ice cream to a child who spoke a different language.”

She nodded seriously.

“I hope so too,” she said. “Because I like ice cream. And I like not being afraid.”

He raised his mug.

“That,” he said, clinking it lightly against her juice glass, “is the best combination there is.”

What The Ice Cream Really Was

On paper, the event at Camp Harbury was a tiny footnote.

“Local women provided frozen dessert to child internees. No disturbances.”

It didn’t change treaties.

It didn’t reverse any battles.

It didn’t erase any crimes.

But for the people who stood there—that day under the English summer sun—it did something important.

For British soldiers, hardened by years of fighting, it cracked the armor just enough for them to see that the small figures behind the wire were not just “Germans.”

They were kids who had gone without sweetness for too long.

For the children, raised on stories of brutal enemies, it offered a confusing but powerful new image:

The same uniform that had marched them into camps was now associated, in at least one memory, with a scoop of something cold and unexpectedly kind.

For adults like Nora and Mrs. Atkins, it was a way to push back against the narrative that the only thing you could do after a war was tally up debts and punishments.

Sometimes, you could also churn milk and sugar and generosity together and hand them out in metal cups.

And for Greta—who would one day tell her own grandchildren about the first time she tasted innocence after war—it was proof that joy could still happen in places that had been built for something else.

“Why did they give it to you?” one of those grandchildren might ask.

“Because someone remembered we were children,” she’d say. “Not just ‘them.’ And because someone had just enough cream left to make the world feel kind for five minutes.”

Five minutes isn’t much.

It doesn’t end conflicts.

It doesn’t rebuild cities.

But sometimes, it’s enough to plant a stubborn little belief in a young mind:

That if cold and sweet can show up in a camp built for hunger and suspicion, then maybe—just maybe—there is more room in the world for unexpected goodness than the uniforms and speeches would have you think.

And that is why, years later, grown soldiers like James and Jacko and captains and nurses and volunteers still found their eyes stinging when they remembered a sunny day, a battered churn, a row of metal cups—

and German child POWs whose first taste of British ice cream made them remember, for a moment,

what it felt like to be

just

children.

News

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned on Them—and How Shocked U.S. Soldiers Intervened in a Mysterious Incident That Led to Three Sudden and Unexplained Dismissals”

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned…

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced U.S. Soldiers Returning Their Missing Children in a Mysterious Encounter That Transformed Fear Into an Unbelievable Wartime Revelation”

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced…

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII Camp and Left German POWs Whispering About a Night They Could Never Explain or Forget”

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII…

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before Their Wounds Worsened — Until American Soldiers Discovered the Hidden Scene Moments Before a Quiet Infection Threatened to Change Their Fate Forever”

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before…

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove Her — Until American Soldiers Intervened in a Stunning Rescue That Uncovered a Hidden Plot and a Wartime Mystery Buried for Decades”

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove…

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone in the Middle of the Night—But What Happened After I Walked Away Revealed a Hidden Secret That Completely Transformed Our Family’s Story Forever”

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone…

End of content

No more pages to load