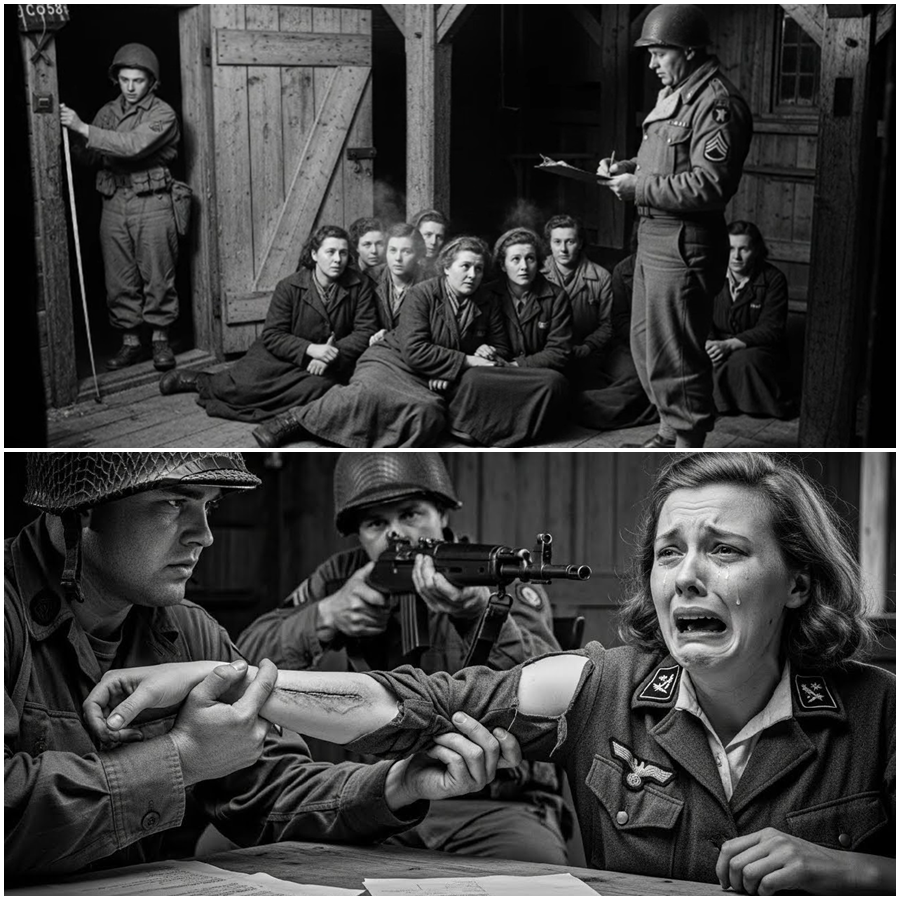

We Need To See Your Secret Marks,” The American Officer Announced, But When German Women POWs Were Marched Into A Locked Hut For A Mysterious Body Inspection, The Reason Behind The Search Left Them Shaking Long After The War Ended

By the time the order reached Barracks 12, the words had already changed shape three times.

“The Americans want to see our scars.”

“No, our tattoos.”

“No, they said secret marks. On the body. Everywhere.”

The women repeated the phrase like a bad taste they couldn’t spit out.

Secret marks.

It sounded like something from a story, not from the cracked loudspeaker that usually barked only roll call numbers and work details.

Anja Keller sat on the edge of her bunk, fingers knotted in the hem of her thin blanket, listening to the murmurs grow.

“They’re looking for traitors,” someone whispered.

“For party loyalists,” another hissed back.

“For those they can use,” a third muttered darkly. “Or punish.”

Nobody knew.

Knowing hadn’t exactly been part of their lives for a long time.

What Anja did know was this:

She had lived through enough inspections to be afraid of the word.

Inspections for lice.

Inspections for contraband.

Inspections for anything that could be counted, measured, controlled.

This one felt different.

Less like checking for disease.

More like looking for something someone expected to find.

“Body inspection,” Marta said flatly from the next bunk. “That’s what the guard called it. Private. In the hut near the gate. One by one.”

One by one.

Anja’s stomach twisted.

She wasn’t the only one.

Before The Wire

The faces in Barracks 12 belonged to women who, in another life, might have shared nothing more than a glance on a street or a brief conversation in a shop.

There was Anja, who had studied bookkeeping and ended up assigned to an office that moved closer and closer to the front until the front swept it up entirely.

There was Marta, the former schoolteacher whose classroom had emptied out one conscription notice at a time.

There was Lotte, who had driven trucks because nobody else in her village knew how to manage the gears on the old army lorries.

There were nurses, typists, signal operators, cooks.

By the end of the war, the lines between “front” and “rear” had blurred so much that they might as well not have existed.

When their unit surrendered, they had walked into captivity together: a column of gray uniforms that didn’t quite fit, carrying small bags and large silences.

The American-run POW camp they were brought to wasn’t the worst place they’d seen.

There were cots. Blankets. A mess line where thin soup and tougher bread appeared twice a day if the trucks arrived on time.

There was barbed wire, yes—but there were also rules pinned to the headquarters door promising that the Geneva Conventions would be observed.

They were registered. Given numbers. Assigned barracks.

“What happens now?” Lotte had asked Anja that first week, sitting beside her on the rough wooden steps.

“We wait,” Anja had said. “For someone to decide where we go.”

“Home?” Lotte had asked.

Anja had heard the hesitation in the single word.

“If home is still there,” she’d replied quietly.

They had gotten used to waiting.

They had not gotten used to surprise.

When the loudspeaker crackled one cool morning with an order none of them had heard before—

“All female prisoners from Barracks 10 to 14 will report in work groups to Inspection Hut 3. Bring identification tags. No bags.”

—surprise arrived hand in hand with dread.

Rumors In The Straw

They had little enough privacy as it was.

Every cough at night, every whispered nightmare was heard by at least ten other people in the crowded wooden building.

So it wasn’t hard for rumors to spread.

“They said ‘secret marks,’” whispered Klara, the youngest of them, eyes wide. “Marks on the upper arm. I heard an American talking to the interpreter.”

“That,” muttered Marta, “would be party tattoos. They’re looking for zealots.”

“Or for people to punish,” said someone else. “You think they will treat us all the same? No. They want to sort us. Good Germans. Bad Germans. Useful Germans. Useless Germans.”

“The ones with marks,” another woman added quietly, “might not come back.”

Silence swallowed that sentence like water around a stone.

Anja shifted on her bunk, feeling every old scar on her own body at once.

None of them were political.

A childhood fall from a tree. A burn mark from a kitchen accident during a blackout. A short, pale line across her thigh from slipping on ice running to a shelter.

None of them were the kind of mark the rumors meant.

But fear doesn’t care about details.

All it hears is inspection and secret and marks and starts writing its own script.

“Maybe they’re looking for numbers,” another voice said, lower. “Like on the arms of… those people they talk about.”

The barracks went very still.

No one said the word camp.

They didn’t need to.

All of them had, by the end, an uneasy awareness that there were other camps, worse camps, places where the wire and the rules had been arranged for purposes no one had explained to them and everyone had half-suspected.

“Why would they look for that on us?” Klara whispered.

“Because they don’t know who is who,” Marta said. “Because to them we are all in the same uniform.”

Even the women who had secretly hated the slogans. Even those who had never voted, never shouted, never raised a hand toward anyone.

The uniform made them all a single shape.

Now, the rumor said, the Americans wanted to see beneath it.

The American Officer

The man at the center of the order didn’t think of it as a terrifying body inspection.

To Captain James Walker, it was, at first, another ugly but necessary task on a list of things that had to be done before the camp could be reorganized.

His commanding officer had called him in two days earlier, a file open on the desk.

“You’ve worked with the interrogation teams before,” the major said. “You know the protocol for identifying certain… affiliations.”

Walker grimaced.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “We check identifiers. Paper trails. Testimony. In some cases, physical marks.”

“Those marks aren’t rumors,” the major said. “We have confirmed reports your… former adversaries… used certain tattoos and symbols to identify special units. We need to know if any of those people are hiding among the non-combatants.”

“And the women?” Walker asked.

The major hesitated.

“Intelligence believes some of them may have been assigned to units with… particular loyalties,” he said. “Their files are incomplete. The chaos at the end of the war shredded half the records. We don’t have time or resources to investigate each one in depth.”

“So we line them up,” Walker finished, “and ask them to prove they don’t have the marks we fear.”

He didn’t like the taste of the words.

“I don’t care for the sound of it either,” the major admitted. “But if we fail to find the worst actors, they slip away and cause trouble later. We’re trying to separate those who held rifles from those who held ledgers. This is one tool.”

Walker rubbed his face.

“If we do this,” he said slowly, “it has to be done… respectfully. They’re prisoners, not livestock.”

“That’s why I’m giving it to you,” the major said. “You still look people in the eye when you talk to them. Some of the others…” He shook his head. “Make sure there’s a female interpreter present. A nurse if you can get one. Keep your men outside the doors. You check arms, shoulders, backs. That’s all.”

“That’s all,” Walker repeated.

He left the office with the file under his arm and a knot between his shoulders.

He understood the logic.

He’d seen what some of those “secret marks” meant. He’d seen pictures and reports from towns where those marked men had been in charge.

But logic didn’t make the idea of ordering already frightened women to bare themselves any easier.

He told himself he would run it like a medical exam.

He hoped that would be enough.

March To The Hut

The women from Barracks 12 were called in the second group.

Barracks 10 and 11 had gone first.

They’d watched them line up, two columns, numbers called by a guard with a clipboard. They’d seen them walk toward the low wooden hut near the inner fence, guards flanking them but keeping a distance.

They’d watched them come back an hour later.

None of them were missing.

All of them were pale.

“What happened?” Anja asked one of them when the groups crossed paths near the water pump.

The woman looked away.

“They looked,” was all she said.

The way she said it made it sound like more than a simple glance.

Inside Barracks 12, they whispered and straightened their clothes as best they could.

“Wear your heaviest shift,” Marta advised Anja. “The one that’s least torn.”

“Why?” Klara asked. “They’re just going to make us take it off.”

“Sometimes how you start matters,” Marta replied. “You walk in like a person, not like a thing waiting to be examined. It changes the way they talk to you. A little.”

It sounded foolish.

It also sounded like the only shred of control they had.

When their numbers were called, they stepped out into the chilly air in two lines.

Anja stood toward the back, heart hammering.

The hut loomed ahead: low-roofed, with a door at either end and small, shuttered windows.

They could not see what was happening inside.

They could only hear the faint murmur of voices and, once, the sound of someone swallowing a sob.

“Forward,” the guard said, not unkindly, but without room for argument.

They marched.

Each step felt too loud.

Inside The Hut

The first surprise was the warmth.

After weeks of cold barracks and long outdoor roll calls, the air inside Inspection Hut 3 felt almost too warm. A stove glowed red in one corner.

The second surprise was who was not there.

No crowd of curious male guards.

No row of smirking faces.

Just three people:

Captain Walker behind a plain table, a German-speaking female interpreter standing slightly to his left, and an American army nurse in a white armband leaning against the wall with a clipboard.

Behind them, a canvas curtain divided the hut into two sections.

The front area had room for six or seven women to stand.

The back, behind the curtain, was hidden from view.

“Bring them in six at a time,” Walker had instructed before they started. “We explain the process. Then we take them one by one behind the curtain. No one is fully undressed in front of the others. We keep it as… decent as possible.”

“Is that necessary?” one of the younger lieutenants had asked. “They’re prisoners. They’ve seen worse.”

“Decency doesn’t stop at the wire,” Walker had replied sharply. “If you’re incapable of understanding that, I’ll find you another assignment.”

The lieutenant had shut his mouth.

Now, as the women entered, the nurse and interpreter exchanged a quick look.

Fear was almost a physical presence in the room.

“Welcome,” Walker began in English, his voice low and calm.

The interpreter repeated in German.

“Welcome,” she said. “We will explain.”

“First,” Walker continued, “you are not in trouble simply for being here. This is not a punishment.”

The interpreter echoed him.

“We have been ordered to check for certain marks on the body,” he said. “Marks that were sometimes used to show membership in special military units.”

“Secret marks,” the interpreter translated, because that was the phrase the women themselves had already been using.

“We will look at your upper arms, shoulders, upper backs, and sides,” Walker said. “No one will touch you more than necessary. The nurse is here to assist if there are medical concerns. The interpreter is here so you can ask questions.”

He let that sink in.

“If you have such a mark,” he added, “we need to know. It does not automatically mean punishment. It does mean further questions. If you do not have such a mark, we will note that, and you will return to your barracks.”

“What about… scars?” one woman asked, voice trembling. “From… before?”

“Scars from life begin before war,” the interpreter softened. “They are not what we are seeking.”

Anja, standing in the back of the small group, tried to breathe slower.

It didn’t help much.

The nurse stepped forward.

“My name is Lieutenant Harris,” she said in careful German, clearly learned with effort. “I am here for medical reasons. If you feel faint, if something hurts, you tell me. You are allowed to stop if you need a moment.”

Her accent was strange. Her eyes were not.

They were the eyes of someone who had seen far too many bodies in far too many states over the last years and who still refused to stop caring.

“Behind the curtain,” Walker said, nodding to the divider, “we will call you one at a time by number. You will remove your blouse and undergarment on the upper body only. No one else will see you. The nurse and I will check for specific patterns. Then you will dress and leave.”

He didn’t say, We are trying to find the worst among you.

He didn’t say, We are trying to decide who will face more questions, more suspicion, maybe more trials.

He didn’t say, We are also, quietly, checking for signs of things no one wrote in your files—injuries, abuse, marks that might tell other stories.

He simply said,

“It will be quick.”

Quick was a relative term.

Fear made minutes stretch.

Being Seen

Anja’s number was called fourth in her group.

By then, she’d watched three women go behind the curtain and emerge again, faces pale but intact, buttoning their blouses with stiff fingers.

None of them had been marched out a different door.

None of them had shouted.

That should have reassured her.

It didn’t.

“Number 4821,” the interpreter called. “Keller, Anja.”

Her legs felt strangely heavy as she stepped past the curtain.

The space behind it was smaller than she’d imagined.

A wooden chair. A narrow bench. The same three people: Walker, nurse, interpreter.

The nurse offered a faint smile.

“Take your time,” she said in German. “You may face the wall.”

Anja did.

Her fingers fumbled with the buttons.

She told herself it was just like washing in the barracks washroom, just like changing clothes in the dark when everyone pretended not to see.

It wasn’t.

There was something in the air here—an awareness that these strangers were looking for something specific beneath her skin.

She slid her blouse off her shoulders, then, with a prickling sense of vulnerability, loosened the thin undergarment and let it fall to her waist.

“Arms,” the nurse said gently.

Anja lifted them.

The air felt cool against her bare skin.

Walker didn’t step closer than he had to.

He didn’t stare.

He scanned.

Right upper arm. Left upper arm. Shoulder blades. Upper back.

Professional. Brief.

Anja stared at the knot in the wooden wall and tried to pretend she was somewhere else.

“Scar here,” the nurse said quietly in English, gesturing toward the pale line along Anja’s side. “Old. No sign of infection.”

“Note it,” Walker murmured.

The interpreter wrote, speaking softly as she did so in German.

“Old scar,” she said. “No concerning marks.”

“Any ink?” Walker asked.

The nurse shook her head.

“Nothing,” she said. “Not even the usual birth marks.”

“Thank you,” Walker said, a phrase meant for Anja as much as for his team. “You may dress.”

Her hands shook as she buttoned her blouse.

He waited until she turned around, fully clothed again, before he met her eyes.

There was something in his gaze she hadn’t expected.

Not pity.

Not triumph.

A kind of weary apology.

“You’re finished, Miss Keller,” he said in German, his accent clumsy but understandable. “You may return to your barracks.”

She nodded, words stuck somewhere between her chest and her throat, and stepped back through the curtain.

Outside, the other women stared.

“Well?” Klara whispered.

“They… looked,” Anja said. “And then they let me go.”

“That’s all?” Lotte asked.

“For now,” Anja replied.

She left out the part where being seen—even briefly, even professionally—had felt like standing on the edge of something sharp.

Who Was Really Being Tested

The inspection went on for hours.

Group after group.

Number after number.

By midday, the nurses had a routine. So did Walker.

Arms. Shoulders. Upper backs. Torso sides.

Scars noted, injuries flagged, nothing else marked.

Once, the nurse stepped closer to inspect a jagged, purpled mark on a woman’s ribs.

“Broken,” she said quietly in English. “Healed badly.”

“From what?” Walker asked.

The woman understood enough to answer, her voice flat.

“From being kicked,” she said in German. “By someone very angry that he was losing the war.”

Walker’s jaw tightened.

“Note for follow-up,” he told the nurse in English. “We may need to bring in a doctor.”

He hadn’t anticipated finding such scars.

He should have.

War left marks everywhere.

Not just on battlefields.

Once, they found what the search had originally been ordered for: a small, stark tattoo in the soft skin of an upper arm, half-hidden by a faded uniform sleeve.

The woman holding that mark stared straight ahead, lips pressed together, as if daring them to comment.

The interpreter’s voice wavered as she translated Walker’s question.

“Were you… proud?” he asked, gesturing to the symbol.

“Once,” the woman said. “Then… afraid. Then… ashamed.”

“Were you forced?” he asked. “Or did you choose?”

“My brother joined,” she replied. “He said it was honor. He said we would be special. He said we would protect our people. Later… when I saw what they did… I wanted to cut it off.”

Walker believed her.

He also knew that belief wasn’t his alone to grant.

Her name went on a different list.

More questions. More investigation.

No immediate punishment.

When she left the hut, the other women in her group avoided her eyes.

Not because they hated her.

Because they were terrified that someone else’s choices might splash onto them.

For Walker, the long morning blurred into a monotonous rhythm of skin and ink and paperwork.

For the women, it was something else.

“It feels like they are deciding what we are,” someone said in Barracks 12 that evening, hugging her knees. “As if they cannot trust what we tell them, only what is written on our bodies.”

“Yes,” Marta said softly. “But remember this too: they also saw the marks made on us. Not just the ones we chose. The ones we did not.”

She rubbed her bad knee absently.

“I watched them today,” she went on. “They wrote down my old injury. They asked how it happened. When I told them it was from a factory collapse, they… looked angry. Not at me. At the idea of a whole building falling on girls like me while officers sat in safe rooms.”

“What good does their anger do us?” Lotte muttered.

“Maybe none,” Marta said. “But maybe it will mean something when they decide who gets what, later. Food. Passes. Transport. It is not nothing to be seen.”

Anja lay on her back, staring at the underside of the bunk above her.

She thought of the way Walker had looked at her after her inspection.

As if he’d been re-evaluating not just her, but himself.

In the hut, he had been the one giving orders.

But as the day had gone on, a strange feeling had settled over him.

It took him until late afternoon to name it.

He was not just testing them.

He was being tested too.

Every time he said, “You may dress,” and turned away politely instead of staring…

Every time he told a jittery guard outside, “No, you cannot come in and watch ‘just to be sure’”…

Every time he chose to note an injury with concern rather than dismiss it as “their problem”…

…he was answering a question the war itself had been asking of everyone in uniform for years:

What will you do with the power you’ve been given over someone who cannot say no?

After The Hut

By the third day, every woman in Barracks 10 through 14 had been through the inspection.

No one had disappeared.

A handful had been called later for additional questioning—those with marks that matched specific patterns, or those whose scars told stories that needed more context.

The rest were left with their fear, their relief, and an odd sense of having been turned inside out and back again.

“What did they find?” Klara asked one evening when the guards were far enough and the barracks had settled into its night rhythm.

“Less than they feared,” Marta said. “More than they expected. That’s usually how it goes when you look closely at people.”

“They saw my childbirth scars,” one of the older women said abruptly, staring at her hands. “I hadn’t thought anyone but the midwife would ever see them. I felt… ashamed. Then the nurse said, ‘You have been brave before.’ It made me want to cry.”

“I have a birthmark on my shoulder,” another said. “I used to hate it. I thought it made me ugly. The interpreter smiled and said, ‘We call that a kiss from the sun.’ I didn’t know whether to laugh.”

Anja listened.

When it was her turn to speak, she surprised herself by telling them the truth.

“I thought,” she said slowly, “that when they said ‘secret marks,’ they were giving themselves another reason to hurt us. Another category to push us into: those with ink, those without. But in that hut… I think they also discovered things they hadn’t been told about us. Things their own files didn’t say.”

“Like what?” Lotte asked skeptically.

“Like the burn on my side,” Anja said. “From when I knocked over a pot in the blackout. All they had in my file was ‘typist, office staff.’ Today the nurse asked, ‘How did this happen?’ and when I told her, she wrote it down. It’s a small thing, but now somewhere, someone knows that once, I tried to make soup in the dark and ended up screaming instead.”

“That doesn’t sound like much of a victory,” Lotte scoffed.

“Maybe not,” Anja replied. “But it’s part of my story. Not one someone else put on me. One I lived.”

Marta nodded.

“Stories live in skin,” she said. “They just rarely get read with kindness.”

Years Later: The Marks That Mattered

In the years after the camp dissolved and the women went their separate ways back into a world trying to decide what to remember and what to forget, the Inspection Hut became a strange kind of milestone in their memories.

Not the worst thing that had happened to them.

Not the best.

A moment when they were forced to confront, literally, what the war had written on their bodies.

Some of them never talked about it.

Others mentioned it only in half-joking tones.

“Remember when the Americans went hunting for our secret marks,” Marta would say over coffee decades later, when a few of them managed to meet. “As if anything about our lives had stayed secret by then.”

In time, what stood out to them wasn’t the embarrassment.

It was the surprise.

The surprise that, when handed an opportunity to humiliate their prisoners, the Americans in charge had chosen instead to create privacy where they could have had none.

The surprise that a nurse had said, “You are allowed to stop if you feel faint,” in a world where they’d been taught that fainting was something to be ashamed of.

The surprise that an officer had said, “You may dress,” and then turned his head politely instead of devouring the sight of their vulnerability.

And, in a few cases, the surprise that someone had noticed marks no one had cared about before:

The cigarette burn on a wrist that turned out to be from a violent superior.

The deep, roped scar on a back that came not from battle, but from a collapsed factory roof no one had ever investigated.

The thin white line on a forearm where a woman had once, in a moment of despair, tried to carve herself out of the story altogether and been stopped by a friend.

Those marks changed some outcomes.

Not all.

There were trials. Questions. New governments that sometimes didn’t care about nuance either.

But when historians later sorted through the camp records, they found something curious in the inspection files from that week:

Alongside the dry notes—“no identifying marks,” “tattoo present,” “old injury”—there were occasional brief comments in another handwriting, smaller, squeezed into margins.

“Fearful. Needed reassurance.”

“Insists she tried to leave unit when she learned of civilian killings.”

“Scar pattern consistent with industrial accident, not fighting.”

“Birthmark on shoulder, not ideological symbol.”

In the key at the back of the file, another officer had scrawled in blue ink:

“Capt. Walker’s personal notes for later review / clemency considerations.”

Whether those notes ever directly saved anyone is hard to prove.

But their existence mattered.

They showed that at least one man in that hut had understood the real truth behind “secret marks”:

That the most important ones weren’t the tattoos the war had stamped on arms in ink.

They were the scars it had left in flesh and bone.

The Question Behind “We Need To See Your Secret Marks”

From the outside, the order sounded clinical.

“We need to see your secret marks.”

From the inside, to the women who heard it echo through the barracks, it sounded like something else:

We want to see your shame.

We want to see your guilt.

We want to see what you cannot hide.

In the end, what the Americans actually saw was more complicated.

Yes, they found what they’d been sent to look for: a handful of symbols that had once meant loyalty to a cause they were determined to uproot.

But they also found:

Stretch marks from children born in basements and barns.

Scars from accidents in factories trying to meet impossible quotas.

Bruises so old they had become part of the landscape of a person’s body.

Bones that had knitted wrong when no one had had time to set them.

They found the physical evidence of lives squeezed between expectation and survival.

The inspection was terrifying.

It was invasive.

It was also, in an odd and uncomfortable way, an acknowledgement:

These women’s bodies existed.

They carried histories.

Those histories were worth reading, not just blaming.

When people later asked Anja what she remembered most from the camp, she didn’t say “the day they made us strip.”

She said,

“The day they asked to see our secret marks, and then, instead of deciding everything from those, they realized that some of what we carried had been put there by others.”

In the end, the biggest secret wasn’t what the women’s bodies revealed.

It was what the inspection quietly exposed about the men in charge:

Given the chance to treat power as a weapon, some of them chose to treat it as a responsibility instead.

That, more than any scar or symbol, was the mark that stayed.

News

Captured German POW Mother Clutched Her Newborn Certain American Guards Would Rip Him From Her Arms, But When The Camp Commander Quietly Slipped A Handwritten Birth Certificate Into Her Shaking Hands The Barracks Realized Their Lives Would Be Changed Forever

Captured German POW Mother Clutched Her Newborn Certain American Guards Would Rip Him From Her Arms, But When The Camp…

“We Haven’t Eaten In A Week,” The Female German Prisoners Whispered Through Tears, But When American Soldiers Opened Their Supply Crates At Midnight, What They Poured Into Shaking Hands Exposed An Act Of Compassion Command Still Tried Desperately To Hide

“We Haven’t Eaten In A Week,” The Female German Prisoners Whispered Through Tears, But When American Soldiers Opened Their Supply…

German Nurses Whispered “Please End Our Suffering” In A Bombed-Out Hospital Cellar, But The Unexpected Answer From A Battle-Hardened American Doctor Ignited A Secret Pact Of Mercy That Changed Every Life In That Ward Forever On Both Sides Of War

German Nurses Whispered “Please End Our Suffering” In A Bombed-Out Hospital Cellar, But The Unexpected Answer From A Battle-Hardened American…

They Laughed When He Bought That Cheap Mail-Order Rifle, But When A Hidden Enemy Sniper Started Dropping Men One By One, The Quiet Farm Boy Turned Into The Unlikely Hunter Whose Next Shot Would Decide Who Walked Away Alive Today

They Laughed When He Bought That Cheap Mail-Order Rifle, But When A Hidden Enemy Sniper Started Dropping Men One By…

Please… My Momma Hasn’t Eaten, The Starving Little Girl Whispered To A Shocked American Soldier, And His Secret Act Of Rule-Breaking Mercy That Night Quietly Rewrote One Occupied Town’s Fate In A Way No One Living There Ever Forgot Forever

Please… My Momma Hasn’t Eaten, The Starving Little Girl Whispered To A Shocked American Soldier, And His Secret Act Of…

German Nurses Watched Their Bombed-Out Village Collapse, Then American Medics Rushed In To Save Their Wounded Families, But The Secret Pact Those Former Enemies Revealed In A Dark Cellar That Night Still Terrifies Historians And Survivors To This Day Worldwide

German Nurses Watched Their Bombed-Out Village Collapse, Then American Medics Rushed In To Save Their Wounded Families, But The Secret…

End of content

No more pages to load