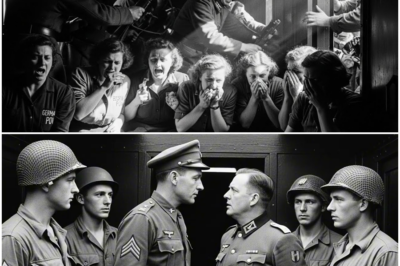

They Were Told Britain Was Ruined And Hated Them, But When German Child POWs Stepped Off The Train On Their First Day There, What They Saw In The Fields, Shops And Schoolrooms Left Them Utterly Speechless And Changed Them Forever

The ship smelled of metal, salt, and fear.

Jonas pressed his forehead against the cold rail and squinted at the line of gray that was slowly becoming land. England. Britain. The island they had been taught to picture as a place of smoke and rubble, of angry faces and empty shops, of people who would never, ever forgive them.

He was twelve years old.

He had never been this far from home.

He had never seen the sea before last week.

He had definitely never imagined arriving in another country as someone counted, tagged, and listed under the heading internee, minor.

Behind him, other children fidgeted, shivered, or stared.

Lisel, eleven, whose braids had come loose days ago.

Karl, who claimed he was fourteen but still looked like he should be climbing trees, not ship gangways.

Elsa, only eight, fingers locked around her older brother’s sleeve so tightly her knuckles were white.

They had been gathered in a transit camp in northern Germany—children and teenagers attached to retreating units, families pulled away from certain zones, youngsters who had followed older siblings west and ended up in the same surrender piles.

Some had uniforms that didn’t quite fit.

Some had none, just whatever clothes they’d been wearing the day the last air raid siren blew.

All of them had one thing in common: they belonged to the losing side of a war they hadn’t chosen.

“Don’t look like you’re impressed,” hissed one boy quietly as a coastline came into focus. “They expect us to be grateful.”

Grateful.

It was not the word Jonas would have picked for this moment.

Tired.

Confused.

Hungry.

Those fit better.

Still, when the ship slowed and the harbor widened around them, his eyes widened despite himself.

He saw cranes.

Warehouses.

Tidy rows of houses.

He did not see ruins.

No shattered walls.

No gaping craters.

No people picking through rubble.

“Where are the bomb craters?” he blurted before he could stop himself.

His older cousin, Lina, standing beside him, answered under her breath.

“Not every city looks like ours,” she said. “We were told… many things.”

Her tone made it clear that they would have to rethink some of those things.

Off The Ship, Onto The List

The British soldiers on the pier did not shout.

They didn’t smile either.

They moved the children down the gangplank in careful lines, checking the small tags pinned to their clothes, comparing them to the long lists on clipboards.

“Name?” one asked.

“Jonas Keller,” he replied, the German syllables thick in his mouth.

The soldier squinted at the card around his neck.

“Keller, Jonas,” he repeated. “Twelve?”

“Yes.”

“Any family with you?”

He gestured at Lina.

“Cousin,” he said in halting English that he’d picked up from radio voices and school lessons that had never been finished.

The soldier nodded.

“Keep close,” he said. “Stay in line. No trouble, we’ll get you fed and sorted.”

Fed.

The word made Jonas’s stomach tighten.

It had been hours since they’d had anything more than thin soup and a crust.

They were herded into a warehouse for initial processing—men at one end, women and children at the other, then the younger ones split off again.

Inside, tables were set up.

Nurses in white, with red crosses on their sleeves.

Men in khaki with pencils.

A woman from the Red Cross with a stack of forms.

They took names.

Ages.

Any illnesses.

There were no beatings. No dogs. No shouting in the ears.

Just tired, practiced questions.

“How old?”

“When did you last see your parents?”

“Do you know where your home is now?”

For some, there were answers.

For many, there were shrugs.

After the forms came the thing that shocked Jonas first.

Food.

Not just a ladle of broth and a tired piece of black bread.

In the big hall at the back of the warehouse, long tables had been set up.

On them: bread so white it looked almost unreal to children used to darker loaves. Bowls of steaming stew. Enamel mugs ready for something hot.

“Form lines,” the sergeant called. “No pushing.”

They lined up.

They tried not to stare.

“You first,” a British cook said, handing Jonas a plate. “You look like the wind could take you.”

The plate was heavier than he expected.

He sat on the end of a bench.

Lina sat beside him.

For a moment, he just looked at the food.

Gravy.

Meat.

Potatoes.

He raised the spoon to his mouth.

The taste was… simple.

Salt. Fat. Something like home, but richer.

He swallowed.

His eyes stung suddenly.

He wasn’t sure why.

“Careful,” Lina murmured. “Not too fast. Or you’ll be sick.”

He nodded and slowed.

Around them, the hall hummed.

Some children wolfed down mouthfuls, unable to pace themselves.

Others ate slowly, suspiciously, as if expecting the plate to be yanked away.

One girl, about nine, pushed her portion toward her younger brother.

“More for you,” she said in German.

The British nurse noticed, frowned, and came over.

“Both,” she said, tapping the girl’s bowl and her chest alternately. “Du auch. You too. Eat.”

The girl blinked.

Then, very carefully, she took a bite for herself.

It was, for many of them, the first time in weeks someone had insisted on them eating, not just the smallest or weakest.

That first meal did not erase the years behind them.

But it planted a small, confusing question:

If this was the land they’d been told would be ruined and vengeful, why did it smell like stew and sound like spoons and offer second helpings?

The Train To Nowhere They’d Heard Of

After the food came movement.

Movement was all they seemed to do these days.

Lines to the ship.

Lines to the warehouse.

Lines to the trains.

“Where are we going?” someone asked.

The British sergeant shrugged.

“Camps,” he said. “Temporary.”

Everything was temporary now.

Temporary beds.

Temporary homes.

The only permanent thing seemed to be uncertainty.

They boarded the train in groups.

Carriages, not cattle cars.

That alone felt wrong.

The compartments had worn seats.

Dusty windows.

Overhead racks.

The doors weren’t locked.

Though soldiers stood at both ends of each carriage, rifles held loosely.

As the train pulled out of the harbor city, the children pressed their faces to the glass.

They saw streets with intact shop fronts.

Women in hats pushing prams.

Men in suits carrying briefcases.

Laundry flapping on lines like flags of normalcy.

Jonas watched a boy on a bicycle racing along a lane beside the tracks, his feet pumping, his hair a messy halo under his cap.

He looked about Jonas’s age.

He could be me, Jonas thought.

Or I could be him.

The idea was so strange it made his stomach flip.

“Do you think they hate us?” whispered Karl from the bench across.

Jonas looked at the villagers they passed.

Some glanced at the train and turned away.

A few waved, cautiously.

One old woman lifted a hand, palm out, not in salute but in something like a blessing.

He didn’t know how to read that.

“I don’t know,” he said.

Fields rolled by.

Green.

So green.

Not the cramped, exhausted patches between ruins he’d seen in the last months at home.

These looked like the textbook pictures from school before the war became the only curriculum.

“They told us everything here was destroyed,” Lina murmured. “But it looks… like a postcard.”

“A postcard with soldiers,” Jonas said.

He nodded toward a small station they slowed past.

Two British soldiers stood smoking on the platform.

Next to them, laughing at something, was a Black soldier in the same uniform.

Same boots.

Same insignia.

“That’s new,” Lina said under her breath.

They had heard rumors that America had many Black citizens.

They had not expected to see Black soldiers in European uniforms.

The British children on the platform didn’t stare at the Black soldier any more than at the others.

They stared at the train full of German children instead.

The worlds were shifting.

And the kids in the carriage were old enough to sense it, even if they didn’t fully understand.

The First Camp

Camp Brambleton was what the sign at the gate said.

It sounded to Jonas more like something out of a fairy story than a place with wire around it.

It wasn’t a big camp.

A ring of low huts.

A few watchtowers.

An open area that had clearly been used as a drill ground at some point.

Now, the drills were different.

The children tumbled off the train and onto the dusty yard, blinking in the bright light.

They were sorted again.

Younger children with mothers or relatives on one side.

Older teenagers and unaccompanied minors on another.

“Age?” the officer asked Jonas.

“Twelve.”

The officer glanced at his list.

“Group C,” he said, pointing. “With your cousin.”

Lina’s tag matched.

They moved to the indicated area.

A British corporal with sandy hair and an easy smile addressed them.

“Right,” he said, and paused.

He glanced at the interpreter.

The interpreter nodded.

The corporal started again, speaking slowly, gesturing to help the words.

“This is not… like prison,” he said. “You are not criminals. You are… how do we say it, sir?”

“Civilians under supervision,” the captain supplied.

“Yes,” the corporal said. “Civilians under… watch. You will have beds. Food. A bit of school.” He pointed at the low hut with a blackboard visible through the open door. “We will not… hurt you. But you must follow rules. No running to the fence. No throwing stones. No shouting at night. If you behave, you will have… some freedom.”

He mimed walking, arms swinging loosely.

The children watched his hands.

His face.

His rifle.

“Some of you,” he continued, “have seen very bad things. We know. We have, too.” He tapped his own chest. “We are… tired. You are tired. Let us not make new bad things here. Yes?”

It was not a stirring speech.

He stumbled over words.

The interpreter smoothed them out.

The kids heard the meaning anyway.

No promises of happiness.

No threat of deliberate cruelty.

A weird, fragile truce.

One of the littlest boys raised a hand.

The corporal nodded at him.

“Will there be… school?” the boy asked in German.

He missed school.

He missed normal.

The interpreter translated.

The corporal grinned.

“Yes,” he said. “We have… Miss Bennett. She will make you say words you do not know yet. You will hate it. And then you will be glad later. That’s how school works.”

A ripple of laughter moved through the group.

“He sounds like our teacher,” Lina whispered.

“Except he has a gun,” Jonas replied.

They were assigned bunks.

Three-tiered structures.

Mattresses.

Blankets folded at the foot.

“Two to a bunk,” the soldier said. “Keep it tidy. No fighting.”

The hut smelled of wood, old wool, and a faint hint of disinfectant.

That last smell made some of the older children flinch.

It reminded them of places where disinfectant had meant something entirely different.

But here, no one shouted for them to undress.

They kept their clothes.

Their tags.

Their thin little bags of possessions.

That night, lying on the middle bunk, Jonas stared at the slats above him.

He heard breathing.

A cough.

A snore.

The distant crunch of boots outside.

His own heartbeat.

No bombs.

The quiet felt wrong.

It also felt like something his body might eventually learn to not fear.

Breakfast: White Bread And Marmalade

“We get this every day?” Otto asked the next morning, eyes huge.

On the table in the dining hut:

Slices of white bread.

Margarine.

A large tin of marmalade, its orange jelly glistening in the weak light.

Porridge that glumped when spooned.

A British cook ladled porridge into bowls.

“Three spoonfuls each,” he said. “Don’t waste it.”

He watched carefully as the children took their portions.

Some, still wary, took only the porridge.

Others reached tentatively for the bread.

When Jonas spread the marmalade on his slice, the smell hit him.

Bitter orange.

Sugar.

He remembered the last jar his mother had managed to buy before the war devoured everything.

“I’m on Christmas duty,” she’d said then. “This will be for when it’s over.”

They had never opened that jar.

He lifted the bread to his mouth.

The taste was both too much and not enough.

Too much because his taste buds, dulled by months of bland and scarce food, lit up and sent memories flooding.

Not enough because no amount of sweet could cover the ghost of hunger.

He ate slowly.

Lina watched the marmalade tin.

“So much,” she whispered. “Do they know how much… that is?”

“Maybe to them it’s… normal,” Jonas said.

The idea was dizzying.

“Normal” was something that looked different in this place.

Normal here was food that arrived, if thin.

Normal here was guards who barked, but didn’t beat.

Normal here was a nurse who scolded a boy for not washing his hands properly.

“We’re not diseased,” the boy grumbled.

“Everyone is, until you prove otherwise,” she replied pragmatically, scrubbing his fingers with rough but not cruel motions.

Later, when Miss Bennett stood in front of the class hut and wrote the English words for “bread,” “jam,” and “plate” on the board, the children paid attention.

Not just because they wanted to learn the language.

Because they wanted to know how to ask for things without always relying on interpreters and guessing.

School And The Question

School felt like the strangest part of that first day.

It wasn’t that they thought they were too old, or too busy, or that learning was pointless now.

It was that school implied a future.

Miss Bennett—Nora, to the other adults, “Fräulein Lehrer” to the kids—walked into the hut with chalk on her fingers and a determined look.

“Good morning,” she said, slowly. “Guten Morgen.”

“Guten Morgen,” they echoed, some shy, some loud.

“We will learn English,” she said. “Anglais. Englisch. We will… read. Write. Play some games.”

She drew a stick figure on the board.

“Boy,” she said, underlining the word.

“Junge,” came the chorus.

She drew another.

“Girl.”

“Mädchen.”

She smiled.

“You see?” she said. “Half the work is already done. Brains like yours are… stubborn. That is good. You need that to push in new words.”

Someone snorted.

Greta raised a hand.

“Why?” she asked.

Nora blinked.

“Why what?” she said.

“Why do we need new words?” Greta clarified. “We are… locked. We are… enemy. We will go… home? One day? Maybe? Why not only… wait?”

Her question was not rude.

It was practical.

Why learn to say “tree” in English if you might be shipped back to a country where the trees had different names, but the same leaves?

Nora took a breath.

She had anticipated this.

She’d asked it herself when taking this post.

“Because,” she said slowly, “the war took many things from you. It does not have to take… everything. Reading, writing, new words… these are things no one can take out of your head once they are in there. They are yours. Whether you are in this hut, or back in your town, or somewhere else. They make you… less trapped. Even here.”

She tapped her temple.

“Freedom,” she said, “starts here, even when this,” she touched the wall, “is not free.”

Silence.

Then Otto rolled his eyes in exaggerated fashion.

“My head is already full,” he muttered. “Of dates and songs and speeches. If I push more words in, something else might fall out.”

“Good,” Nora said cheerfully. “Let them. We will replace.”

The children laughed.

That day, learning “cup, spoon, bread” in English was not a revolution.

It was, however, the first time in a long time that learning felt like something other than propaganda or survival training.

And that made it quietly radical.

First Evening, First Letters

That evening, after supper (more porridge, more bread, a ladle of thin stew that still tasted better than their last weeks back home), the children were given a surprise.

“Paper,” the interpreter announced, holding up a bundle. “Briefpapier. Letters.”

A hush fell.

“Each of you gets one sheet today,” he said. “You may write to family. Or to whoever you… think might be there. The letters will be read by censors. Some may not reach. But some will. Try.”

Not everyone knew addresses.

Not everyone had anyone left.

But the idea of being allowed to reach out, even in this limited way, moved them.

Jonas stared at the blank page.

What could he write?

“Dear Mother, I am in England. It is not what they said. There is marmalade. I had ice in my drink. I am in a hut. There is a teacher. I am afraid.”

He wrote instead:

“Liebe Mutter, I am safe. We have food. I am with Lina. There is school. If you get this, please write. I miss you.”

He folded the paper.

Signed his name carefully.

Handed it in.

Lina did the same.

Karl wrote to nobody in particular.

“Dear whoever reads this,” he scrawled. “I have not seen my father since the winter. If he is alive, tell him Karl is alive too. I am in a place called Brambleton. There is grass. I do not want to be here. But I am glad there are no bombs.”

He gave the letter to the interpreter, who glanced at it, eyebrows lifting, then put it with the others.

Later, in the guard hut, James sorted the letters for the censors.

His German was shaky.

But he understood enough to feel a sting.

“Glad there are no bombs.”

He thought of his little brother scribbling, “Dear James, Mum says hello. The Anderson shelter leaks.”

He thought of the symmetry.

He thought of the absurdity.

Then he put the letters in the post bag.

Because that was his job now too:

To help messages cross wires and water.

Not Heaven, Not Hell

By the time the children crawled into their bunks that night, their heads were buzzing.

Not from explosions.

From impressions.

England had not been the smoking, broken ruin some had pictured.

Nor had it been the golden land of abundance the sight of the supermarket shelves from the train had briefly suggested.

It was something in between.

The camp was not a holiday.

The wire was real.

So were the rules.

But so were the porridge, the nightshirts, the crayons Nora had set out in the classroom, the battered ball someone had produced for games.

In their first day, the German child POWs had seen things that scrambled their expectations:

British soldiers who carried heavy buckets, not whips.

British cooks who barked but slipped an extra spoonful onto small plates.

A British teacher who taught them new words without insisting they forget their old ones.

They had also felt things they weren’t sure how to name:

Relief at the absence of immediate danger.

Guilt at having full stomachs while imagining what might be happening in the rubble back home.

Suspicion that kindness might somehow be a trap.

As Jonas lay in the dark, listening to someone snore softly across the hut, he whispered to Lina on the bunk below.

“Is it… allowed,” he asked, “to like anything here?”

There was a pause.

Then she whispered back.

“It is allowed to breathe,” she said. “Start with that.”

Years Later: Remembering The First Day

Decades after the fences came down, Jonas sat at a kitchen table in a peaceful Germany, his grandson’s history book open in front of him.

“This says children were sometimes kept in camps in Britain,” the boy said, frowning. “Not just soldiers. Is that true?”

Jonas smiled wryly.

“Yes,” he said. “They called us ‘internees.’ As if the word made much difference.”

“Was it… awful?” his grandson asked. “Like the big camps we learn more about?”

Jonas shook his head slowly.

“Not the same,” he said. “Nothing was like those. Brambleton was… confusing. We were not free. But we were not… tortured. They fed us. They taught us. We were afraid anyway.”

“Is that when you first had marmalade?” the boy asked, eyes bright.

“Yes,” Jonas said. “On white bread. I thought it was a dream.”

He paused.

“And your first day?” his grandson prompted.

“What about it?” Jonas asked.

“You always say your first day in Britain is when you realized that the world was… bigger than you thought,” the boy said. “Why?”

Jonas leaned back.

He saw, in his mind, the harbor.

The cranes.

The houses.

The boy on the bicycle.

The guard handing him a plate without sneer or smile.

The green fields from the train.

The school hut.

The ice-cold pump in the yard where British and German children washed hands side by side.

“Because,” he said slowly, “I had been told many things about that island. That it was decadent, corrupt, collapsing. That its people hated us to the bone. That we would be lucky to get crusts. Then I stepped off the train and saw… life. Ordinary life. Pots on stoves. Children in streets. And I realized that most of what we fight over is in the heads of grown men, not in the faces of children.”

His grandson frowned.

“That’s not in the book,” he said.

“It rarely is,” Jonas replied.

He tapped the page.

“Books tell you about treaties and battles,” he said. “They don’t tell you about the taste of marmalade after months of watery soup. Or the shock of seeing your ‘enemy’ trip and bleed and make the same noises of pain you do. Or the way a teacher’s voice can sound the same whether you’re in Berlin or Brambleton.”

The boy nodded slowly.

“Will you tell my class?” he asked. “About the marmalade.”

“Only if they promise not to waste it,” Jonas said, eyes crinkling.

In the end, the first day in Britain for those German child POWs was not a single, neat moment of revelation.

It was a collection of disorienting, small experiences:

White bread.

Green fields.

A camp that smelled of porridge, not gas.

Guards who were wary but not gleeful.

A teacher who wrote their names on a board with care.

They had been told Britain was ruined, vengeful, almost mythical in its hunger for payback.

Instead, they found a tired country that, despite its own scars, had decided to give its former enemies’ children something scandalously simple:

Food.

Words.

Time.

And that, more than any speech, any poster, any later memorial, is what lodged in their memories:

That on their first day in Britain, they were treated not as symbols of a defeated nation—

but as what they had always been,

underneath uniforms and labels and fear:

children.

News

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned on Them—and How Shocked U.S. Soldiers Intervened in a Mysterious Incident That Led to Three Sudden and Unexplained Dismissals”

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned…

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced U.S. Soldiers Returning Their Missing Children in a Mysterious Encounter That Transformed Fear Into an Unbelievable Wartime Revelation”

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced…

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII Camp and Left German POWs Whispering About a Night They Could Never Explain or Forget”

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII…

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before Their Wounds Worsened — Until American Soldiers Discovered the Hidden Scene Moments Before a Quiet Infection Threatened to Change Their Fate Forever”

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before…

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove Her — Until American Soldiers Intervened in a Stunning Rescue That Uncovered a Hidden Plot and a Wartime Mystery Buried for Decades”

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove…

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone in the Middle of the Night—But What Happened After I Walked Away Revealed a Hidden Secret That Completely Transformed Our Family’s Story Forever”

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone…

End of content

No more pages to load