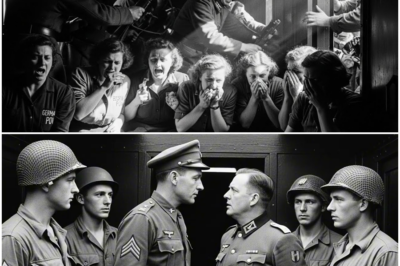

“Sleep Without Your Clothes,” The British Soldier Ordered The Terrified German Women Prisoners, But When Their Nightmares From Other Camps Exploded Into Panic, The Real Reason For The Rule — And Who Finally Changed It — Shocked Everyone On Both Sides Of The Wire

When the order first came down, it was only a line in a file.

“Effective immediately: female internees in Hut C will sleep without clothing. Underwear only. Clothes to be collected each evening for delousing and inspection. Return in the morning. Purpose: hygiene and security.”

To the British captain at Camp Greyford, it seemed practical.

The lice problem in the women’s sector had flared again.

There had been a rumor of a contraband knife stitched into a hem.

Someone higher up had muttered about “standardizing procedures.”

He initialed the memo, passed it to the sergeant, and went back to wrestling with food inventory.

He didn’t hear the sentence the way the women did when the sergeant translated it that evening through the bars.

He heard: “Hygiene, security, clothing check.”

They heard something else entirely.

“Sleep without your clothes.”

Words that tasted like humiliation in their mouths.

Words that echoed, in far too many minds, with scenes from other places.

Places that did not have British flags outside.

Places where “take off your clothes” had meant something very different.

The Camp At The End Of The Map

Camp Greyford sat on a wind-swept patch of English countryside that never made it onto postcards.

A few low huts.

Watchtowers.

A double run of wire.

By the autumn of 1945, it held a collection of women nobody had quite known what to do with when the war ended:

Former nurses.

Clerks.

Auxiliary staff snapped up in sweeps with retreating units.

Civilians from the wrong zones at the wrong times.

Some had volunteered eagerly for service years earlier.

Some had been pulled in with the tide and dropped here.

The British called them “internees” on paper.

The women called themselves many things, depending on the day:

Prisoners.

Survivors.

Fools.

Sinners.

Just tired.

They’d been through other camps.

German transit centers.

Evacuation barracks.

Once, for two of them, a place whose very name had become a hissed warning: Ravensbrück.

They did not talk about that much.

They didn’t have to.

The flinch in their shoulders when anyone slammed a door spoke enough.

The women’s compound at Greyford was, technically, humane.

They had cots with blankets, not lice-infested straw.

Two meals a day, thin but predictable.

Access to a latrine that didn’t overflow every week.

A small patch of yard where they were sometimes allowed to walk under watchful eyes.

They also had rules.

So many rules.

Roll call at dawn.

Lights out at nine.

No loitering near the fence.

No hoarding bread.

No speaking to guards unless spoken to.

Most of the rules were bearable.

They were used to carrying other people’s orders around like extra layers of clothing.

They wrapped them around themselves and moved.

Then came the new one.

The one that felt like someone had reached under all the layers and grabbed skin.

“Without Your Clothes”

Sergeant Michael Hughes was not a cruel man.

He’d joined the army at nineteen, fought in Italy, and seen enough blown-apart towns and bodies to last several lifetimes.

When they posted him to Greyford as “senior NCO, women’s sector,” he’d joked bitterly to a mate:

“From mortars to laundry duty. My career’s really on fire.”

He didn’t speak German, beyond a handful of phrases.

“Raus.”

“Schnell.”

“Essen.”

He relied on Corporal Blake, whose grandmother had been from Hamburg and who’d learned enough of her language as a boy to muddle through.

That evening, standing on the packed dirt outside Hut C, Hughes unfolded the order and frowned.

“Clothes off at night?” he muttered to Blake. “Bloody hell. What next, bedtime stories?”

“It’s for the fumigation, Sarge,” Blake said. “Lice are back. And you heard about the razors they found sewn into the seams. They want everything on hooks so they can spray the lot. Fewer places to hide nonsense.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Hughes grumbled. “I know the why. Doesn’t make the how any less awkward.”

He glanced at the door.

On the other side, forty-odd women waited.

Some were older than his mother.

Some were younger than his little sister.

He’d been shot at by their countrymen.

He’d lost friends to their countrymen.

He also had no interest in seeing them without clothes.

“Let’s get this over with,” he said.

He banged on the door.

It opened a crack.

Elsa, the informal leader inside by virtue of being loudest and least afraid to argue, peered out.

“Hurry up,” Hughes said. “Fall in. Schnell. You know the drill.”

They shuffled out in their usual lines, cardigans pulled tight.

The autumn air had teeth.

Blake cleared his throat.

“Instrucciones nuevas,” he said in clumsy half-Spanish out of long habit, then corrected himself, “Neue Anweisung. New instruction.”

Forty faces turned toward him.

“From today,” he read, “you will, at night, sleep without clothes. Nur Unterwäsche. Underwear only. You will give outer clothes to the guard at lights-out. We fumigate. We inspect. In the morning, clothes back.”

A ripple went through the group.

A physical shiver.

Elsa’s eyes narrowed.

“You want us naked?” she demanded in German, voice sharp.

“Nein,” Blake said quickly, flushing. “No. Not naked. Under things only. Like… pyjamas. You keep your… shirts you sleep in. Just no uniforms. No dresses. Clothes go to cleaning.”

“Why?” another woman—Lotte—asked tightly.

“Hygiene,” Blake said. “Lice. Bugs. And… security. No place to hide razors. Nebelkerzen. No sneaking outside in full clothes at night. Regeln.”

Rules.

He thought that would explain it.

He didn’t see the way two of the older women went suddenly pale.

He didn’t hear the words that detonated quietly in their heads.

“Clothes off.”

Not here.

Before.

Barking in a foreign language.

Hands.

Eyes.

Cold.

“No,” one of them, Frieda, said, shaking her head. “No. I will not.”

Hughes bristled.

“This isn’t optional,” he said, voice hard. “You’re in our camp. Our rules. Clothes off at night, laundry gets sorted, you get them back. It’s not complicated.”

He thought he sounded firm.

In control.

Inside Hut C that night, his words mutated.

Night Terrors In Hut C

When the guards collected the clothes at lights-out, the hut became a new landscape.

Piles of dresses, cardigans, skirts disappeared into sacks.

Hooks rattled as uniforms came down.

In the sudden chill, bare arms goosepimpled.

Some women slipped into their long under-slips.

Others wore vests and knickers, shivering as blankets went up around them like flimsy walls.

The single bulb overhead cast everything in hard yellow.

“We did this before,” Frieda whispered, sitting on her bunk, arms wrapped around herself. “I will not do this again. I will not let them—”

“Hush,” Elsa snapped, more sharply than she meant. “This is not there. This is here. They do not shout. They do not laugh. They just… take clothes.”

Her own heart hammered.

At Ravensbrück, clothes had been a rare comfort.

They hid hollows.

They provided tiny illusions of privacy in overcrowded rooms.

They were the only barrier between skin and eyes.

Here, at least, they still had blankets.

Pillows.

But for many, the act of handing over outer garments felt like stepping back toward a line they thought they’d left behind.

“What if they don’t bring them back?” Lotte whispered in the dark. “What if this is the first step? Today clothes. Tomorrow… what?”

“Tomorrow we still have knickers,” muttered Greta from the other end, trying for humor and landing in bitterness.

Some women lay stiffly.

Others curled into themselves.

Memories shifted under their skins.

Even those who had never been in the worst camps had heard enough.

Lists.

Numbers.

“Undress, schnell!”

Here, no one shouted.

No one pointed.

But the echo was loud anyway.

In the guard hut, Hughes took the sacks of clothing from the night duty private, dumped them in the fumigation shed, and lit a cigarette.

“Reeks in there,” the private said, wrinkling his nose. “Like vinegar and dead moths.”

“Better dead moths than live lice,” Hughes said.

He tried not to think about the women in their bunks, shivering.

He tried not to picture his own mother, who always slept in a full nightgown “in case of fire.”

His mind did it anyway.

He ground the cigarette out harder than necessary.

“This is temporary,” he muttered to himself. “Soon as the fumigation’s done, we’ll calm it down.”

He underestimated how fast fear grows in the dark.

Misunderstanding As A Third Language

The next morning, when the guards returned the clothes, a few women almost cried with relief.

Frieda hugged her faded dress as if it were back from the dead.

Elena, who had sewn her own blouse in a camp sewing room with stolen thread, pressed the fabric to her face.

For two days, the routine repeated.

Clothes off.

Clothes fumigated.

Clothes back.

The lice problem improved.

The contraband problem diminished.

The women’s anxiety did not.

On the third night, one of the younger women, Marta, refused to hand over her skirt.

“It goes,” Hughes said, gesturing.

She shook her head, eyes wild.

“Nein,” she said. “No. It was mine. Before. I made it. I keep it. I am not—” Her voice broke.

Elsa intervened.

“Give it,” she hissed in German. “Better to be cold than marked as trouble.”

Marta shook.

Then yanked the skirt off, throwing it into the sack as if it had burned her.

That night, she woke screaming.

Elsa caught her before she fell from the bunk.

“It’s not there!” Marta sobbed. “They took Petra. They took—”

“Hush,” Elsa said, rocking her. “You’re here. England. Greyford. Not there.”

The next morning, Elsa marched to the wire.

Hughes was on duty.

He saw her striding toward the fence and stiffened automatically.

“Back from the wire,” he barked. “You know the rules.”

“I know too many rules,” she snapped in German. “We need to talk.”

Blake, sensing an explosion, came over.

“She wants to… talk,” he translated.

“Nothing to talk about,” Hughes said. “Orders are orders.”

“Orders are breaking them,” Elsa retorted. “You think you are being clever with your rules. Fewer tools. Less lice. You don’t see what it does in their heads.”

She tapped her own temple.

“In here,” she said. “Kopf. Head. It is not just cloth. It is…”

She groped for the right English word, found none.

Blake watched her face, saw the strain.

He’d seen men with eyes like that after heavy fighting.

“What does it do?” he asked gently, in German.

Elsa inhaled.

“It makes… ghosts,” she said. “From other camps. Other showers. Other… rooms. They hear ‘clothes off’ and they are back there. You say ‘sleep without clothes’ and you think of laundry. They hear… something else.”

Hughes frowned.

He knew, in a vague way, about the worst stories from the other camps.

He also knew that thinking about them too much made sleep harder.

“We’re not them,” he said stiffly. “We’re not… doing those things.”

“I know,” Elsa said. “In the day. The brain knows. In the night? It does not. All it hears is, ‘You have no layer left.’”

Blake translated, haltingly.

The sergeant rubbed his face.

The fumigation shed had been a neat solution on paper.

Reality was messier.

“I’ll talk to the captain,” he said finally. “See if we can… adjust.”

Elsa snorted.

“You have that power?” she asked.

“No,” he admitted. “But he does. Someone has to tell him what it looks like from your side of the fence.”

He surprised himself with the last sentence.

He hadn’t realized until he said it how different the hut looked in his mind versus hers.

The Captain Who Didn’t Know

Captain Andrew Miles prided himself on being efficient.

He’d organized supply runs in North Africa, coordinated troop movements in Italy, and handled a small mutiny over tea rations in a way that had only cost him one broken mug and a few sharp words.

Running a POW camp wasn’t what he’d imagined doing when he first put on a uniform.

But it was work that needed doing.

He approached it like a logistics problem.

Food in.

Waste out.

Health monitored.

Security maintained.

It never occurred to him, initially, that emotional safety should be part of the equation.

When Hughes knocked on his prefab office door and said, “We may need to rethink the clothing order,” Miles frowned.

“Already?” he asked. “Hasn’t even been a week.”

“Sir, it’s doing their heads in,” Hughes said. “They’re having nightmares. Proper ones. Elsa—that tall German woman—came to the wire this morning looking like she’d bite the fence. Says it’s… reminding them of other camps.”

Miles stared.

“We’re fumigating,” he said. “We’re meeting hygiene standards. We’re not… doing anything untoward. If they can’t tell the difference, that’s hardly our problem.”

Hughes shifted.

“With respect, sir,” he said carefully, “if we can reduce their agitation without making more work for ourselves, it might be worth it. Less screaming at night means less stress, fewer incidents. Maybe we can tweak it. Let them keep one outer layer. Or issue some of our surplus shirts as ‘night clothes’ so they don’t feel… stripped.”

Miles tapped his pen on the desk.

“What, give them our shirts?” he said. “We have enough problems getting proper kit for our own side.”

He thought of the requisition forms, the memos about shortages.

He also thought of the last quarterly report.

It had a section on “prisoner disturbances.”

Hut C had been quiet until this week.

Now, the nurse had noted an increase in anxiety.

Night terrors.

One woman who’d started refusing to undress at all, even for washing.

Practicality warred with pride.

“This is why we have rules,” he said slowly. “To avoid improvisation. First we let them keep jumpers, then they’ll be hiding contraband again.”

“Sir,” Hughes said, “they’re not asking to keep everything. Just… something. So they don’t feel like they’re waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

Miles raised an eyebrow.

“The other shoe?” he repeated.

“You know what I mean,” Hughes said.

He didn’t.

Not really.

He only knew that every instinct that had kept him alive so far said, Listen to the people closest to the problem.

“Fine,” he said at last. “We’ll issue camp nightshirts. Plain. No pockets. They hand in their own outer clothes. That covers hygiene and blades. But at least they’re not lying there with nothing but their smalls between them and the whole world.”

He picked up his pen.

“I’ll need to ask requisitions,” he grumbled. “They’ll complain. Again.”

He signed the change order anyway.

The Nightshirts

Requisitions hated him for a full week.

“This is a prisoner-of-war camp, not a blooming holiday camp,” the quartermaster complained as he handed over a stack of coarse cotton shirts. “What next, slippers?”

“That’s not a terrible idea,” muttered the nurse under her breath.

“Shut up, Nurse Green,” Miles said, not unkindly.

The nightshirts were simple.

Long.

Unflattering.

Made from the same material as standard issue undershirts, just extended.

When Hughes and Blake carried them to Hut C and explained the revised order, a ripple went through the women again.

This time, different.

“From tonight,” Blake said in German, reading from the new note, “you will still give your own clothes at lights-out. But you will be issued camp shirts to sleep in. Long. No pockets. Clothes will be deloused, inspected, and returned. Shirts will remain in the hut.”

He held up one of the garments.

It looked, to him, like a large pillowcase with a neck.

To the women, it looked remarkably like something they remembered from before.

A shift.

A nightgown.

Not elegant, but decent.

Marta, who had refused to remove her skirt three nights before, reached out and touched the fabric.

“Wie ein… Nachthemd,” she murmured. “Like a nightshirt.”

“Exactly that,” Blake said. “Camp Nachthemd. Not from home, but… something.”

Elsa’s shoulders sagged slightly.

Relief?

Or just exhaustion?

“You listened,” she said in English, surprising him. “You changed.”

He shrugged.

“Sergeant complained for you,” he said. “Captain listened. That is new for us too.”

That night, when the clothes sacks went around, there was still tension.

There would be for a while.

But when the women pulled the nightshirts over their heads, the feeling was… different.

They still felt the vulnerability of being outside their own garments.

But there was a barrier again.

Thin, scratchy, uniform.

But theirs, in a new way.

Not taken from them.

Given.

It mattered.

It didn’t erase memories.

Nothing could.

But it softened their edges.

The nightmares didn’t vanish.

Trauma doesn’t take orders from cotton.

They did lessen.

And in the guard hut, when Hughes heard only one scream instead of four, he considered it proof enough that the paperwork had been worth it.

What The Order Really Meant

On the surface, “Sleep without your clothes” had been just another camp regulation.

A line on a form meant to address practical concerns.

Hygiene.

Contraband.

Standardization.

The shock came from what it meant when it collided with history.

For the British, it was a procedure.

For many of the German women, it was a trigger.

It made them relive rooms where “clothes off” had been the prelude to humiliation, violence, dehumanization.

The British didn’t intend that.

But intent doesn’t cancel impact.

What mattered in the end wasn’t that the original order had been written.

It was that it didn’t stay unexamined.

A sergeant listened to a shouted complaint through a fence.

A corporal translated not just words, but tremors beneath them.

A captain, trained to care more about rules than feelings, was persuaded—grudgingly—to adjust.

A small, stupid thing, some would say.

Issuing nightshirts.

Allowing a thin layer of fabric.

But in that thin layer lived something larger:

A recognition that care in captivity is not only measured in calories and square meters.

It’s also measured in whether the people under your control feel like human beings or objects.

Years later, when former internees told their stories, they rarely mentioned the policy itself.

What they remembered, more often, was the change.

“The first days,” one woman would say, “we thought it was starting again. The taking. The stripping. Then they realized. They gave us shirts. It was… not nothing.”

On the British side, few official histories recorded this minor administrative adjustment.

But if you asked veterans who’d served at camps, some might say:

“You know what made the biggest difference? Not just food or letters. It was when we learned that our own procedures could hurt in ways we didn’t see, because we didn’t carry what they carried. Once we learned that, we became… better jailers. If such a thing exists.”

The Daughter’s Answer

Years later, Lina—no longer a frightened girl in a thin dress, but a woman with grown children—sat at her kitchen table in a reunified Germany.

Her daughter, Hannah, leafed through a university textbook about World War II.

“There’s nothing here about what it was like… there,” Hannah said, frowning. “In the smaller camps. The temporary ones. Only the big names. The very bad places.”

“They were very bad,” Lina said quietly.

“I know,” Hannah said quickly. “I’m not saying… I just mean. Your story. Greyford. That order. It’s not in the book.”

Lina smiled wryly.

“Why would it be?” she asked. “It doesn’t fit in timelines. It was only… a few weeks. A small place.”

“It mattered to you,” Hannah said. “Tell me again. About the clothes.”

Lina took a breath.

“When they said ‘sleep without your clothes,’” she began, “we thought… the worst. We had heard stories. Some had lived them. For a few nights, it was… as if the ghosts had been invited in. Then the sergeant did something strange. He listened. He told his captain. They changed the rule. They gave us shirts.”

She paused.

“In that moment,” she continued, “we realized that not every uniform was the same. Some could ‘just follow orders’ forever. Some could say, ‘This order hurts in a way we didn’t intend. We can change it.’”

“And you?” Hannah asked. “What did you do with that… realization?”

Lina stared at her hands.

“I kept it,” she said. “In the same drawer where I kept my anger. Sometimes one was on top. Sometimes the other. But when people later tried to tell me ‘they were all monsters’ or ‘we were all victims,’ I remembered the boy carrying your grandmother and the nightshirt being handed through the door. And I knew the truth was… more complicated.”

Hannah nodded slowly.

“Does that make forgiveness easier?” she asked.

Lina smiled sadly.

“Forgiveness is too big a coat for me to wear every day,” she said. “But it makes hatred… heavier. Harder to hold. Especially when I remember that in the worst years, even one stupid cotton shirt handed across a fence could mean the difference between reliving a nightmare and believing, just a little, that the world might someday be kinder.”

In the end, the British soldier’s order—“Sleep without your clothes”—terrified the German women POWs not because of what it was on paper, but because of what it echoed.

What changed everything wasn’t the initial command.

It was what happened when the women behind the wire asked, in their own way:

“Do you see what this does to us?”

And the men on the other side, for once in that terrible decade, answered by doing something very un-war-like:

They listened.

They adjusted.

They put a layer back between skin and world—

not to weaken discipline,

but to remember

that even in captivity,

even after everything,

dignity is a kind of security no fence can provide.

News

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned on Them—and How Shocked U.S. Soldiers Intervened in a Mysterious Incident That Led to Three Sudden and Unexplained Dismissals”

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned…

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced U.S. Soldiers Returning Their Missing Children in a Mysterious Encounter That Transformed Fear Into an Unbelievable Wartime Revelation”

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced…

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII Camp and Left German POWs Whispering About a Night They Could Never Explain or Forget”

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII…

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before Their Wounds Worsened — Until American Soldiers Discovered the Hidden Scene Moments Before a Quiet Infection Threatened to Change Their Fate Forever”

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before…

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove Her — Until American Soldiers Intervened in a Stunning Rescue That Uncovered a Hidden Plot and a Wartime Mystery Buried for Decades”

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove…

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone in the Middle of the Night—But What Happened After I Walked Away Revealed a Hidden Secret That Completely Transformed Our Family’s Story Forever”

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone…

End of content

No more pages to load