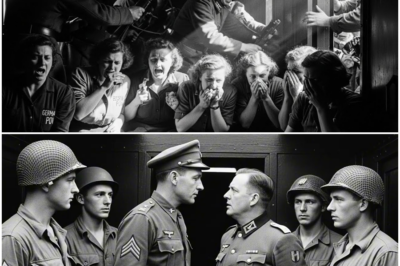

“She’s Only Eighteen And She’s Pregnant!” The Sergeant Whispered In Disgust When The Terrified German POW Collapsed, But What The American Nurses Secretly Did For The Young Enemy Woman Behind Barbed Wire Would Change How Everyone In That Camp Understood Mercy Forever

The first time Anna heard the word out loud in English, it sounded like an accusation.

“Pregnant.”

The American medic said it under his breath, half in surprise, half in exasperation, as he knelt in the mud of the camp yard beside her limp body.

“She’s only eighteen, and she’s pregnant,” he muttered. “For God’s sake…”

The woman lying unconscious at his feet didn’t understand his words exactly.

But she knew that word.

Pregnant.

It existed in her language too.

Schwanger.

She’d heard it whispered about girls in the village back home.

She’d heard it hissed angrily at women in the city.

She’d heard it prayed over quietly at kitchen tables, hands folded around cups of weak coffee.

Now, it applied to her.

And she was lying in the dirt of a prisoner-of-war camp, in a uniform that no longer meant anything, while foreign hands checked her pulse.

If anyone had told her that the next people to lift her, bathe her, and protect the child she wasn’t sure she even wanted to keep alive would be American nurses—the “enemy”—she would have laughed in their face.

She didn’t laugh much anymore.

War had taken that from her long before it took her freedom.

The Girl Who Tried To Disappear

Anna Bauer had not started the war as a soldier.

She’d started it as a student.

At fifteen, she’d sat in a schoolroom near Bremen, conjugating verbs, sketching in the margins of her notebook, dreaming vaguely of teaching or nursing or anything that would let her leave the tiny apartment over the bakery where flour dust settled in her hair every day.

By seventeen, school had shrunk.

Then vanished.

Shelves replaced textbooks.

Orders replaced lessons.

“You can help,” the posters said.

“You should help,” the people in uniforms said.

They were very convincing.

So she signed forms.

Took a short training course.

Stood in a line with other girls as a woman with a clipboard assigned them roles.

“Signals,” the woman said to one.

“Kitchens,” she said to another.

“Transport,” she said when she got to Anna. “You’re tall. You can lift. You can see.”

The transport unit was supposed to be “safe.”

Behind the front.

Moving boxes, not bodies.

The first time they handed her a clipboard with a list of names instead of supplies, she understood exactly how much she hadn’t understood before.

She didn’t ask questions out loud.

She saved them for her diary.

For the nights when she lay on her narrow cot and stared at the wooden slats above, mouthing words she’d never say in daylight.

“This is wrong,” she whispered into her thin pillow. “But I am a small piece. If I leave, another piece will fit into my space. Maybe at least I can be gentler.”

War, she discovered quickly, did not care about her efforts to be “gentle.”

War cared about numbers, fuel, movement.

And then, one night, it cared enough to find her convoy.

Bombs had punctuated her life for months.

Always somewhere else.

Falling on other cities, other people’s streets.

That night, they fell on the road outside the depot where her unit slept.

In the explosion, everything blurred.

Fire.

Screams.

Orders shouted and unheard.

When she woke, she was lying in a ditch with mud in her mouth and a ringing in her ears.

The ring dissolved into a shout.

“Hands up!”

The voice was English.

She raised her hands.

The war was over, someone said later in the camp.

They said it as if that made sense of anything.

The Camp With Too Many Questions

The camp was nothing like the posters back home had promised would never happen to girls like her.

It was rows of low huts.

Barbed wire.

Guards who were young and old at the same time.

At first, Anna moved through it in a daze.

She followed the other women—clerks, drivers, nurses, some barely older than she was, some old enough to be her mother—as they lined up for meals, for roll call, for latrines.

She learned quickly:

Don’t linger.

Don’t argue.

Don’t attract attention.

She tried to disappear into the crowd.

It was easier than she thought it would be.

She was one of so many.

Names on lists.

Faces behind numbers.

The first missed period didn’t even register.

She told herself it was stress, bad food, too much walking.

Her body had never felt entirely like hers since she’d joined the transport unit.

The second missed period made her stomach lurch.

The third made her throw up behind one of the huts one morning.

“Again?” whispered Lotte, the girl who slept on the bunk above hers. “Maybe it’s the stew.”

“It’s not the stew,” Anna whispered back.

She didn’t say what it was.

She didn’t have to.

Lotte’s eyes widened.

“Oh,” she breathed. “Oh, Anna…”

They didn’t speak of it again for a week.

Not until a new problem arose: the morning sickness wasn’t just mornings anymore.

One afternoon, lining up for soup, Anna’s vision narrowed to a tunnel.

The pot at the front swayed.

The ladle blurred.

The world tilted.

She went down without even feeling her knees hit the ground.

“She’s Only Eighteen”

The American medic’s name was Private Sam Turner.

He’d grown up in a small town in Ohio, where the only foreign words he’d ever heard regularly were on the menu at the diner.

War taught him others.

Kaputt.

Schnell.

Gefangene—prisoner.

He’d learned enough German to understand “Headache,” “Stomach,” “Pain.”

He hadn’t expected to say “Pregnant” in a muddy camp full of German POWs.

He knelt in the dirt beside Anna, fingers searching for a pulse.

It fluttered.

“Get her up,” he told the two women nearest her. “Careful. Not by the arms—under the shoulders.”

They obeyed.

She was light.

Too light.

He glanced at her face.

Pale.

Beads of sweat on her forehead.

The dark rings under her eyes.

“She’s only eighteen,” one of the guards muttered, checking her file card later in the makeshift infirmary. “Hell of a time to pick for this.”

Sam shook his head.

“It’s not like she got to pick much of anything,” he said under his breath.

“Still. Pregnant,” the guard said, as if the condition were somehow more outrageous than the war that had dropped her here.

Sam didn’t reply.

He was thinking of his sister back home.

Seventeen.

Last letter full of talk about dances and maybe a boy.

He imagined her in this bed.

Flinched.

The camp had a small medical hut.

It wasn’t meant for complicated cases.

It had cots, a few cabinets, a hand-washing station, and a smell of carbolic that never quite left anyone’s nose.

What it had now, uniquely in this sector, was a small team of American nurses.

They weren’t supposed to be here long.

They’d been sent “temporarily” to organize vaccinations, treat minor infections, and consult on sanitation.

None of them had planned on involving themselves too deeply in the lives of prisoners.

They ended up knowing those lives better than they knew their own schedules.

The Nurses

Lieutenant Jane Parker had been a nurse for four years.

She’d spent them in a pressure cooker.

Field hospitals.

Triage tents.

Rows of men with missing limbs, missing eyes, missing pieces of themselves.

She thought she’d seen every way a body could break.

Then she saw the camp.

She saw women whose breaking wasn’t visible.

Not at first.

Shadowed eyes.

Careful postures.

The odd mix of relief and shame that came with surviving when others hadn’t.

“We can’t fix everything,” she told her small team the first day they arrived. “We’re here to keep people alive, prevent infection, and not make things worse.”

“Not making things worse” turned out to be more complicated than she’d thought.

One afternoon, when Sam carried Anna into the hut, Jane’s first thought was, “Too young.”

Her second was, “Of course.”

War didn’t pause for pregnancy.

Her third thought was practical.

“Get her on bed three,” she said. “Elsie, start water going. Ruth, I need the blood pressure cuff.”

While they worked, the guard hovered.

“You know she’s a prisoner,” he said, as if they might have missed that detail.

“Yes,” Jane said. “And she’s also carrying a baby.”

He shifted uncomfortably.

“What are we supposed to do with… that?” he asked, gesturing at Anna’s midsection without quite looking at it.

“Treat her,” Jane said flatly. “Like any other patient. The politics above our heads don’t change the fact that her body is doing what women’s bodies have done, inconveniently, since forever.”

He opened his mouth.

Closed it.

Walked out.

“Doesn’t like the idea of enemy babies,” Elsie muttered, adjusting the blanket.

“Enemy babies don’t stay enemies if you don’t raise them that way,” Ruth replied, checking Anna’s pulse.

Jane pressed her lips together.

She’d seen the aftermath of civilians caught between fronts.

She’d also seen the way some of her colleagues hardened their faces when treating anyone with the wrong uniform.

She refused.

“Pain doesn’t wear a flag,” she’d told her commanding officer when he’d raised an eyebrow at her casualty lists.

Now, as she examined Anna, she frowned.

There was a bruise along the ribs.

Old.

Another on the upper thigh.

Newer.

Her stomach was small.

Too small for how many weeks along she suspected she might be.

“Malnourished,” Jane murmured. “Dehydrated. Overdue for rest.”

“How can someone be both over- and under-?” Elsie asked.

“War,” Jane said. “It does that to people.”

The Secret Nobody Wanted To Discuss

When Anna woke, it was to the unfamiliar feeling of clean sheets and a roof that didn’t leak.

Her first instinct was to tense.

To protect the space around her.

Then a hand touched her shoulder—gentle, but firm.

“Easy,” a woman’s voice said. “You’re safe. No one’s going to hurt you here.”

Anna blinked.

The nurse leaned into view.

Brown hair tucked under a cap.

Lines at the corners of her eyes from squinting in too much bright light over too many bandages.

She spoke slowly.

“You’re in the medical hut,” she said, in English, then repeated in halting German. “Sanitätsbaracke. You fainted. Now we help.”

Anna understood enough.

“How… long?” she asked, German making her throat feel dry.

“Only a few hours,” the nurse said. “You’ve been asleep. You needed it.”

Anna’s hand fluttered, almost of its own accord, toward her abdomen.

The nurse saw.

“Yes,” she said gently. “Pregnant.”

The word hung between them.

Anna swallowed.

“For how… long?” she whispered.

“Hard to say without proper tests,” the nurse replied. “Four, five months, perhaps. Far enough that we must be careful. Not so far that it’s too late to help.”

Help.

That word was new in this context.

She’d been avoiding thinking about the baby.

When they’d been captured.

When they’d been marched.

When they’d been processed.

She’d told no one.

Not even Lotte.

She hadn’t wanted anyone to put their opinions, their judgments, their fear on top of the weight she already carried.

Now a stranger had put a name to it.

Pregnant.

Anna felt panic rise.

“What… happens… now?” she asked, the words stumbling out.

Jane inhaled.

“We take care,” she said simply. “For you. For baby.”

“But I’m… prisoner,” Anna said. “Feind. Enemy.”

“Yes,” Jane said. “And also a young woman whose body needs support. Both can be true.”

Anna’s eyes filled.

“I didn’t want…” she began, then stopped.

She didn’t have the vocabulary to explain everything that had led to this.

The night.

The officer.

The “favor” she “owed.”

The way saying no had never really felt like an option.

The shame.

The stubborn, irrational hope that maybe, if she carried the child, it would somehow redeem the wrongness that had started it.

Or maybe she just hadn’t had the energy to get in anyone else’s way.

“Doesn’t matter how it happened,” Jane said, misreading the hesitation but not the depth of emotion behind it. “Right now, our job is simple. Food. Rest. Check your blood. Make sure you don’t collapse again in the latrine line.”

She offered a small smile.

“You’re not the first,” she added. “We’ve seen women with babies in worse places than this. War doesn’t stop life from happening. It just makes us more responsible for how we handle it.”

Kindness Where It Wasn’t Expected

Kindness in a POW camp was risky.

On both sides.

For the prisoners, accepting it could feel like betrayal.

For the staff, offering too much of it could draw suspicion or reprimand.

The nurses found ways around that.

They couched their extra efforts in the language of necessity.

“Pregnant women need more calories,” Jane told the kitchen officer. “If we want her to carry to term without complications, she needs extra rations.”

“Extra?” he repeated. “For them?”

“For her,” Jane emphasized. “And the baby. Healthy babies mean fewer medical complications. Fewer complications mean less strain on our limited resources. Think of it as cost-saving.”

He’d grunted.

“Fine,” he’d said. “What do you want?”

“Lentils,” she’d replied. “And whatever fresh you can spare when shipments come.”

For the guards, they explained Anna’s time in the infirmary as “medically necessary” to avoid fainting in roll call and “not a luxury.”

For the other women in the hut, the nurses tried to set a tone.

They spoke to Anna not like to a child, but like to someone whose body had taken on a heavy task without asking permission.

“Here,” Ruth would say, handing her a cup of watered-down milk. “Not much, but it helps.”

“Sit,” Elsie would insist when Anna tried to stand in line too long. “You’re not skipping. You’re making a human. That’s enough to earn a seat.”

At first, the other prisoners were suspicious.

“She gets more soup,” a woman grumbled.

“She was fainting,” another pointed out. “Would you rather she collapse on your bunk?”

“She’s carrying more,” Lotte said one evening, when whispering drifted through the barracks. “Let her carry less of everything else.”

Slowly, the envy turned to something else.

Protectiveness.

If someone jostled Anna in line, a hand would reach out to steady her.

If someone tried to cut in front of her, an older woman would snap, “Let the girl eat.”

She didn’t understand all the English words the nurses used.

But she understood tone.

She heard her name—“Anna”—used gently, without ranking, without barked orders.

She heard “baby” said with a softness she hadn’t expected from the other side of the barbed wire.

She watched, stunned, as Jane argued with a superior one day in low, fierce English when a supply of prenatal vitamins was misallocated to a different unit.

“We are not talking about giving chocolate to prisoners,” she said. “We are talking about preventing anemia. This is basic. If we deny basic care because we dislike their uniforms, we’re no better than what we claim to fight.”

The officer had grumbled, but relented.

Later, Jane had shrugged when Ruth praised her.

“I didn’t join up to be a selective nurse,” she said. “Either we’re here to protect life, or we’re just mechanics with bandages.”

News From Outside

News in the camp came in fragments.

Announcements over loudspeakers.

Whispers from new arrivals.

Bits of newspaper used as packing.

Germany had surrendered.

The war in Europe was ending.

For some prisoners, this news was a crack of light.

Repatriation.

Home.

Rebuilding.

For others, it was a shadow.

Uncertain futures.

Destroyed cities.

Families they might not find.

For Anna, it was both.

Freedom for her might mean being sent back to a place that no longer existed in the form she’d left it.

It also meant a question:

What would happen to the child inside her under a different flag?

She asked Jane one day, in halting words, the fear she carried like a stone.

“When I… leave,” she said, hand on her stomach, “what about… him? Or her?”

Jane wiped her hands on her apron and considered.

“We don’t decide that,” she said honestly. “Officially, you’ll be processed like other POWs. But we’ve made notes in your file. Medical. Someone in admin will see them.”

“Will they… take it?” Anna whispered.

The idea had haunted her.

That someone might see her baby as property. As a problem to be solved by separation.

“No one has that right,” Jane said firmly. “Not anymore. Not if we can help it.”

She wasn’t naïve.

She knew policies could be cruel.

She also knew people.

And she’d seen, recently, the way some officers’ eyes softened when they passed the infirmary window and saw Anna knitting tiny socks from scraps of wool Lotte had bartered.

“We may not be able to change everything,” Jane said. “But we can put your story in ink in places where decisions are made. It’s harder to ignore ink than it is to ignore faces.”

She kept that promise.

On the day a delegation came to review the camp’s medical records before beginning repatriation, Jane handed over a file.

“Pregnant POWs,” she said. “We have three. This one”—she tapped Anna’s name—“is due in late autumn.”

The delegate frowned.

“Repatriation might take longer than that,” he said. “Transport lines are a mess. Paperwork too.”

“Then we either make exceptions,” Jane said, “or we plan for one more birth here. But we do not let her slip through cracks because no one wanted to bother.”

He nodded slowly.

“I’ll flag it,” he said.

Later, in another tent, he looked at Anna through the window as she sipped soup, one hand unconsciously cradling her belly.

She looked younger than his own daughter.

He made a note with a firmer pen stroke than usual.

The Birth

Anna did not go home before the baby came.

Logistics, as predicted, were slow.

The war had ended on paper.

On the ground, it kept echoing in shortages, missing trains, confusing orders.

By the time leaves on the sparse camp trees began to yellow, her ankles had swollen.

Her back ached constantly.

The baby kicked against her ribs like a protest drum.

She was both terrified and oddly calm.

Life had given her no control over big things—war, capture, politics.

This, at least, was a process humans had walked through for millennia.

Pain, breath, pushing.

She clung to that thought during labor.

It started at night, with a cramp that made her hiss.

By morning, waves of pain rolled through her, each one stronger.

Jane, who had never delivered a baby without a full hospital’s worth of backup, found herself revisiting training she’d never thought she’d need here.

“Breathe,” she told Anna. “In. Out. Again.”

The other women in the barrack became a support crew.

Lotte wiped Anna’s forehead.

An older woman from another hut held her hand and told a story about giving birth in a cellar during an air raid.

“You’ll be fine,” she said in rough German. “At least this roof doesn’t shake.”

Anna wasn’t sure what “fine” meant anymore.

But she knew, in the peaks of pain, that she was not alone.

When the baby finally arrived, with a lusty cry that startled birds from the wire, everyone exhaled.

“A girl,” Jane announced, relief making her eyes shine. “Healthy. Loud. That’s good.”

She placed the tiny, squirming bundle on Anna’s chest.

For a moment, all the labels fell away.

There was no prisoner.

No enemy.

No camp.

Just a young woman staring at a pair of fists the size of walnuts, tiny fingernails, a mouth opening and closing like a small pink flower.

“She’s… real,” Anna whispered.

“Yes,” Jane said softly. “And she needs a name.”

Anna thought of names she’d heard shouted, whispered, prayed.

She chose one that had always sounded like a question mark and an exclamation point at once.

“Lena,” she said. “After my aunt. She survived everything. Twice.”

“Lena,” Jane repeated.

She wrote it in the file, under “Infant.”

Not “Baby of POW.”

Just “Lena Bauer.”

Leaving

Months later, when Anna finally stepped onto a truck that would take her and her daughter toward a border, the nurses stood by the gate.

“You’ll manage,” Ruth said, squeezing her arm. “You’ve been managing since before we met you.”

Jane handed her a small package.

“From the staff,” she said. “Diapers. A bit of ointment. Some powdered milk. I wish it were more.”

Anna’s throat closed.

“I have… nothing,” she said. “When I left home, I carried a bag. That’s gone. Everything is…”

She gestured vaguely—gone, burned, exploded, lost in a maze of logistics and artillery.

“You have her,” Jane said, nodding at Lena, whose head rested in a borrowed shawl tied at Anna’s chest. “And you have the fact that you kept her alive through all this. That’s not nothing.”

Anna swallowed.

In awkward English, she said, “Thank you. For… not hating me.”

Jane smiled sadly.

“I have seen too much pain to waste energy hating its victims,” she said. “Go. Make something different, if you can.”

The guard checked names.

Anna climbed onto the truck bed with other women.

As it rumbled away, she looked back.

Saw the nurses’ white caps shrinking.

Saw the barbed wire.

Saw the hut where her body had been treated kindly by people she’d been told were her enemies.

Her world had become complicated.

But one thing was simple:

When she whispered “She’s only eighteen and she’s pregnant” to herself those first days in the infirmary, it had been with fear and shame.

Now, with Lena’s warmth against her, she thought:

“She’s only eighteen and she had help.”

From hands that should have pushed her away.

From voices that should have stayed hard.

From nurses who had decided that their oath to care did not end at the flag on someone’s sleeve.

Years Later

In a small town in a country trying to rebuild itself, a woman in her thirties stirred soup on a stove that had dents in the enamel and a pot that had seen better days.

A little girl sat at the table, swinging her feet.

“Mama,” the girl said. “Tell me again about the place with the fence.”

Her mother, Anna, smiled wryly.

“Of all the stories in the world, you always choose that one,” she said.

“It’s my beginning,” Lena said. “You said so.”

“Yes,” Anna replied. “It is.”

She told it different ways, depending on the day.

Sometimes she spoke more about the hunger.

Sometimes about the fear.

Always, she included the nurses.

“The American women?” Lena would say, eyes wide.

“Yes,” Anna said. “The ones who told the men to give us extra soup. The ones who argued with their officers. The ones who handed me a screaming, wrinkled little creature and said, ‘She’s yours.’”

“Were they nice?” Lena asked.

“They were… kind,” Anna said. “Sometimes, there is a difference. ‘Nice’ smiles and leaves. ‘Kind’ stays and sees. They saw me. Even when I didn’t want anyone to.”

She didn’t romanticize the camp.

It had been what it was: a place of scarcity, of forced waiting, of too many questions and not enough answers.

But she held on to that thread of kindness like a lifeline.

Later, when Lena asked her, “How did you not hate them all?” she answered,

“Because someone in their uniforms held my hand when I was afraid, and someone in mine had caused their grief. It was not simple. So my feelings could not be simple either.”

In her old age, when Lena had children of her own, Anna would sit in a faded armchair and say,

“If people tell you kindness is weakness, you tell them about the nurses. They were surrounded by orders to stay hard. They chose soft hands anyway. That’s not weak. That’s strong in a different direction.”

What The Story Really Was

Years later, when historians interviewed former prisoners and staff, they often wanted big stories.

Escape attempts.

Sabotage.

Dramatic conversions.

Some of them missed the quieter ones.

Like the story of an American camp nurse arguing with an officer over vitamins for “enemy” pregnant women.

Or the story of a medic looking at an eighteen-year-old on a cot and thinking of his sister.

Or the story of soup ladled a little more generously into a certain bowl when no one official was looking.

Or the story of a German girl who learned, in the unlikeliest place, that care can come from where she’d been taught only threat lived.

“She’s only eighteen and she’s pregnant!” had been, originally, a whisper of exasperation.

Over time, in the retelling, it became a different kind of sentence.

A statement of fact that called for action, not judgment.

“She’s only eighteen and she’s pregnant—so what are we going to do about it, now that she’s in front of us, whether we like it or not?”

The American nurses answered with bandages and blankets.

With extra soup and firm boundaries.

With paperwork that recorded the existence of a baby who might otherwise have stayed a rumor.

They couldn’t stop the war.

They couldn’t fix every injustice that had put Anna in that bed in the first place.

They couldn’t even guarantee what kind of world Lena would grow up in.

But they could, in that small, smelly hut with its makeshift pharmacy and wobbly cots, do this much:

Refuse to let uniforms dictate who deserved care.

And in doing so, they gave an eighteen-year-old prisoner something the war had tried very hard to steal from her:

The idea that kindness was still possible—

even from the hands

she’d been taught to fear.

News

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned on Them—and How Shocked U.S. Soldiers Intervened in a Mysterious Incident That Led to Three Sudden and Unexplained Dismissals”

“Hidden Chaos Inside a Collapsing WWII POW Camp: Why Terrified German Women Begged for Help as Their Own Guards Turned…

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced U.S. Soldiers Returning Their Missing Children in a Mysterious Encounter That Transformed Fear Into an Unbelievable Wartime Revelation”

“They Prepared for the Worst Fate Imaginable, Yet Witnesses Say a Shocking Twist Unfolded When Terrified German POW Mothers Faced…

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII Camp and Left German POWs Whispering About a Night They Could Never Explain or Forget”

“The Midnight Command That Terrified Captive Women: Why a Mysterious Order From an American Guard Echoed Through a Hidden WWII…

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before Their Wounds Worsened — Until American Soldiers Discovered the Hidden Scene Moments Before a Quiet Infection Threatened to Change Their Fate Forever”

“Desperate German POW Girls Secretly Tried to Saw Off Their Shackles in a Remote Camp Building, Hoping to Escape Before…

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove Her — Until American Soldiers Intervened in a Stunning Rescue That Uncovered a Hidden Plot and a Wartime Mystery Buried for Decades”

“‘They’re Going to Take My Life!’ a Terrified German POW Woman Cried Moments Before a Secretive Group Tried to Remove…

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone in the Middle of the Night—But What Happened After I Walked Away Revealed a Hidden Secret That Completely Transformed Our Family’s Story Forever”

“My Stepmother Screamed ‘Leave This House Right Now or I’ll Call the Cops,’ Forcing Me to Pack My Bags Alone…

End of content

No more pages to load