Christmas Eve 1944: 300 British Teen POWs Were Told They’d “Disappear” Before Dawn—Until One German Officer Locked the Gate, Destroyed the Transfer Orders, and Risked His Rank to Move Them to Safety, Leaving a Secret Note Unread for Decades Today

The cold had its own sound in December 1944.

It wasn’t just the wind. It was the way breath turned tight, the way boots squeaked on frozen ground, the way metal seemed louder than it should have been—gate hinges, canteens, keys. The kind of cold that made teenage faces look older, because the skin around the eyes hardened first.

That night, the British boys were huddled in a drafty outbuilding behind a wire fence—three hundred of them, give or take, depending on who counted and when. Some were seventeen. Some said eighteen because it sounded stronger. A few were younger than they admitted, the way boys sometimes are when the world starts demanding adulthood at gunpoint.

They weren’t in a clean camp with a permanent routine. This was a temporary holding place, the kind that appeared near a rail spur or a repurposed depot when the front moved faster than the paperwork could follow. Straw covered the floor in thin patches. The air smelled of wet wool, old wood, and the faint sourness of bodies that had gone too long without proper warmth.

The boys had been told—by guards, by rumors, by the tone of men who no longer cared to explain—that they would be moved again before dawn.

Moved where? Nobody said.

But “moved” wasn’t the word that scared them. They’d been moved before. Marches, trucks, train cars, lines that never ended. They knew the geography of captivity: you go where you’re sent. You do what you’re told. You learn to stop asking “why,” because “why” is a luxury.

What scared them was the other word—never spoken directly, but carried in glances and half-heard phrases:

No witnesses.

In war, that phrase doesn’t need an official stamp to feel real. It lives in the fear of people who have seen how quickly the world can decide you are inconvenient.

And on Christmas Eve—while the rest of Europe waited for midnight bells or simply waited for morning—300 British teenage prisoners believed they were minutes from a transfer that many of them would not survive.

Then the German officer arrived.

And instead of speeding the transfer, he locked the gate.

The Boys Who Didn’t Look Like “Enemy”

The first thing Captain Karl Ritter noticed, according to a later recollection from his driver, was that the prisoners were too young to hate properly.

Hate requires a certain stability: enough food, enough sleep, enough ideological certainty. The boys in that shed had none of those things. They sat close to each other, shoulders touching, sharing whatever warmth their bodies still knew how to generate. Their coats were mismatched. Their hands were raw. When they tried to look brave, it came out as stiffness.

They looked like schoolboys who’d wandered into a nightmare.

Ritter was not a saint, and he wasn’t a secret rebel in a dramatic movie sense. He was a professional officer in a collapsing military system, tasked with keeping order in a region that was dissolving into confusion as the winter offensive raged and supply lines broke. He had spent years following orders. He understood chain-of-command. He understood consequences.

He also understood something else: when chaos rises, the worst decisions often hide inside “routine transfers.”

Especially when the prisoners are young.

Especially when the transport paperwork is vague.

Especially when nobody wants extra mouths to feed.

Ritter had been told to escort a group of British prisoners to the railhead and “ensure the movement is completed quickly.”

Quickly is a dangerous word in wartime.

It can mean efficiency. It can also mean: don’t ask questions.

Ritter asked a question anyway.

“How old are they?” he asked the sergeant on duty.

The sergeant shrugged. “English boys,” he said, unimpressed. “Soldiers.”

Ritter stepped closer to the fence and looked at them again.

A boy met his eyes—wide, stubborn, trying to look like a man. His cheeks were hollow in the cold. His hands were stained with dirt that no amount of rubbing would remove.

Ritter spoke in clipped English—enough to get by.

“How old?” he repeated.

The boy hesitated, then answered with the most common lie of teenage captives:

“Eighteen.”

Ritter’s gaze didn’t soften into sentimentality. It sharpened into calculation.

Because the lie confirmed what he already knew.

The Transfer Order That Didn’t Add Up

Paperwork is the quiet engine of war.

It tells you where to march, what to move, who to count, who belongs to which category. When the paperwork is clean, systems function. When it’s messy, people vanish—sometimes by accident, sometimes because mess is convenient.

Ritter requested the transfer packet. It arrived in a thin folder stamped twice, signed once, and missing key details: destination listed only as a code; “escort” marked as “local”; prisoner classification ambiguous.

Ambiguous paperwork was normal that winter.

But it still bothered him.

Not because he was sentimental about the enemy. Because ambiguous paperwork meant liability. And Ritter had learned that in collapsing systems, liability always tries to attach itself to the nearest responsible person.

He scanned the roster. It listed “British personnel, captured during recent operations.” No mention of age. No mention of medical condition. No mention of oversight. No mention of Red Cross documentation—at least not in the packet he saw.

A second sheet—tucked behind the first—contained a short line of instructions: “Proceed immediately. No delays.”

Ritter’s jaw tightened.

“No delays” often meant someone higher up wanted the matter finished before anyone asked why.

He turned to the sergeant. “Where are the wagons?” he asked.

The sergeant pointed toward the yard—two trucks idling, their headlights off, their engines a low growl in the cold.

Ritter looked at them and felt the smallest, most dangerous thought appear:

If they leave in those trucks tonight, nobody will be able to prove what happened on the road.

That thought wasn’t certainty. It was possibility.

But in war, possibility is enough.

The Christmas Eve Factor

People love to imagine Christmas Eve as a pause in violence, a universal hush, a rare moment of humanity.

In 1944, it wasn’t a pause. It was a thin layer of tradition laid over exhaustion.

But tradition can still do something powerful: it can remind people they are not only machines.

When Ritter arrived at the holding site, he noticed a small detail that shouldn’t have mattered—but did.

A guard had hung a tiny pine branch near the administrative hut, more habit than celebration. It was barely visible in the darkness.

Ritter stared at it for a second longer than necessary.

A pine branch. A gesture. A reminder that the calendar insisted on meaning even when the world refused it.

He thought of his own younger brother, drafted late, barely trained, sent somewhere east months earlier. He thought of a letter he’d received weeks ago—short, hurried, full of optimism that felt forced.

He thought of how young people become “soldiers” in paperwork long before they become soldiers in the soul.

Then he did something that still shocks people who study wartime behavior.

He said, “Stop the transfer.”

The sergeant blinked. “Captain—”

Ritter cut him off. “Stop it. Now.”

The Gate That Didn’t Open

Orders get tested in small moments. A gate opens or it doesn’t. A key turns or it doesn’t.

Ritter walked to the outer gate himself. He took the keyring from the guard without asking. Then he locked the gate again, deliberately, and put the keys in his own pocket.

The guard stared. The sergeant frowned.

“Captain,” the sergeant said, lowering his voice, “we have instructions.”

Ritter looked at him. “Yes,” he said evenly. “I do too.”

He didn’t explain further, because explaining creates witnesses, and witnesses create complications.

Instead, he turned and walked back toward the administrative hut, the transfer folder in his hand.

Inside, he sat at a desk under a dim lamp, pulled out a pen, and began rewriting reality.

The Oldest Weapon: Bureaucracy

Most people imagine “saving” someone in war requires a dramatic confrontation.

Sometimes it requires a stamp.

Ritter knew the system well enough to use it against itself. He couldn’t openly defy higher authority—not without triggering immediate retaliation. But he could slow the machine with the machine’s own tools: documentation, classification, and procedure.

First, he reclassified the prisoners in a way that forced delays: he added a medical review requirement due to “exposure risks” and “youth status.” He didn’t write anything emotional. He wrote it like an officer protecting operational readiness: young prisoners in poor condition were a liability during transport, and liabilities create incidents.

Second, he changed the escort requirement: no local escort, only an officially logged escort with a specific signature from the regional command. That signature could not be produced overnight.

Third, he created a paper trail that would make the prisoners harder to erase: a roster copy placed in a separate envelope addressed to a neutral administrative office, with an instruction to log receipt by morning.

Then he did the most dangerous thing of all.

He took the original “immediate movement” sheet and tore it in half.

Not theatrically. Quietly. As if removing a splinter.

He folded the torn pieces into his coat pocket.

If anyone demanded the sheet later, he could claim it was missing, misfiled, lost in the chaos. That was believable in 1944. Paper vanished constantly.

But “missing paper” was different from “completed transfer.”

Missing paper buys time.

The Part Nobody Expected: Warmth First

Ritter left the hut and walked toward the outbuilding where the boys were held. A guard opened the inner door, hesitant.

Ritter stepped inside.

The boys fell silent.

He could feel their eyes on him. They were trying to read his face, because facial reading is what captives do when information is scarce. One wrong tone can mean everything.

Ritter’s voice came out flatter than he intended, because emotion is dangerous in a place like this.

“You will not move tonight,” he said in English.

The boys didn’t react at first. They didn’t trust it.

Ritter looked at the guard. “Hot water,” he ordered. “Now. And blankets. And soup if you can find it.”

The guard blinked again, confused by the priorities.

Ritter repeated it, sharper. “Now.”

Within minutes—time that felt unreal—the first pot of hot liquid arrived. Not a feast. Not a miracle. Just warmth delivered as a deliberate choice.

A soldier distributed cups under Ritter’s supervision. A blanket pile appeared—thin wool, worn, but real.

The boys accepted the cups the way starving people accept food: carefully, as if the offer might disappear if they moved too fast.

One boy whispered, “Is this a trick?”

Ritter didn’t answer. He didn’t need to.

He simply stayed there long enough for them to understand the gate was still locked.

The Rumor That Shifted: “Someone Up There Said No”

Prisoners are experts at rumor, because rumor fills gaps when truth is withheld.

By midnight, the rumor had changed.

It was no longer “they’re moving us at dawn.”

It was: “Someone up there said no.”

The boys didn’t know Ritter’s name. They didn’t know his rank. They didn’t know his motives.

But they knew the difference between chaos and restraint.

Restraint looks like warm water in a winter shed. Restraint looks like a guard told not to shout. Restraint looks like blankets distributed without humiliation.

And in 1944, restraint was shocking.

The Pressure Arrives

At around one in the morning, a vehicle arrived at the administrative hut.

An officer from a neighboring unit—hard-faced, impatient—stepped inside. His boots left wet marks on the floor.

“Why hasn’t the transport left?” he demanded.

Ritter kept his tone neutral. “Medical hold,” he said. “Youth group. Exposure. Paperwork needs correction.”

The officer sneered. “You’re delaying.”

“I’m preventing an incident,” Ritter replied.

The officer slammed a hand on the desk. “Do you know how many movements we’re coordinating? We don’t have time for your… sensitivity.”

Ritter didn’t flinch. He held up the revised packet.

“Read it,” he said.

The officer skimmed, then frowned. “This isn’t what command ordered.”

Ritter nodded once. “I’ve requested confirmation signatures,” he said. “Until then, movement is not compliant.”

It wasn’t a heroic argument. It was a bureaucratic trap.

If the officer forced the transfer without the signatures, he would become responsible for whatever went wrong. And “whatever went wrong” in winter transport could be many things—illness, collapse, escape attempts, accidents—none of which anyone wanted attached to their name.

The officer stared at Ritter for a long moment.

Then he did what many wartime officials do when the risk calculation changes.

He backed down.

“Fine,” he said, voice tight. “But in the morning, they go.”

Ritter nodded. “In the morning,” he agreed.

After the officer left, Ritter sat alone in the hut for a minute and stared at his hands.

He had bought hours.

Hours can be everything.

The Real Rescue: The Morning Reassignment

Ritter’s goal was never “keep them here.” This holding site was too exposed, too unstable. If higher command returned with fresh orders, the boys could be moved again—fast.

Ritter needed a safer destination: a recognized POW camp with oversight, routine, and records. A place where teenage prisoners could not easily “vanish” into winter roads.

So before dawn, Ritter sent a runner to the nearest command post with a request framed as a logistical necessity: re-route the prisoners to a proper facility due to “youth classification” and “transport risk.” He included a note that a delayed movement could reduce operational strain by consolidating prisoners with existing administrative infrastructure.

It was the kind of language commanders listen to.

At first light, a reply arrived—brief, reluctant, stamped.

Approved.

Not out of kindness, necessarily.

Out of paperwork logic.

Ritter had done it: he had moved the boys from the category of “temporary inconvenience” to the category of “logged responsibility.”

That shift—paper to paper—was the rescue.

The Walk That Felt Like a Second Chance

The boys were moved later that day, not in the shadowy trucks, not in the chaos of midnight, but in a more formal convoy with documented escort and a destination that could be tracked.

They still walked in the cold. They still shivered. They still didn’t know what the future held.

But they weren’t being moved as shadows anymore.

They were being moved as documented prisoners.

One boy—called “Tommy” in a later account—looked back at the gate and saw Ritter standing near the hut, face unreadable. Tommy raised a hand slightly, unsure if he was allowed.

Ritter didn’t wave like a friend.

He simply nodded once.

A small gesture, but one that meant: You’re still on the map.

The Secret Note

Years later, survivors would argue about whether Ritter left a note. Some swore he did. Others said that was legend.

But one version of the story persists because it’s so human it hurts:

Before the convoy departed, Ritter slipped a folded paper into the pocket of a teenage prisoner’s coat—a boy who spoke the best German and had been answering questions for the others.

The paper contained a single sentence in careful English:

“Tell your people you were treated as prisoners, not as a problem.”

No signature. No rank. Just a message.

Why would he do that?

Because in war, truth becomes contested territory. Ritter may have wanted a witness—one witness—who could say, later, that not everyone chose the worst option when the night offered it.

After the War: Why No One Spoke

After 1945, stories like this often sank into silence for decades.

British survivors didn’t always talk about captivity. When they did, they focused on endurance, on camaraderie, on the long wait to go home. “A German officer helped us” was not the kind of sentence that fit the public mood of neat moral categories.

And on the German side, speaking about “saving enemy teenagers” could be dangerous in a different way. In some circles, it could be framed as disloyalty. In others, it could be dismissed as self-serving.

So the story survived in fragments: in reunion conversations, in a letter tucked in a drawer, in a grandson hearing “Christmas Eve 1944” spoken with a strange pause.

What “Saved” Means in This Story

Did one officer “save” 300 boys by himself?

Not in the fantasy sense. Systems and circumstances mattered. Luck mattered. The chaos of winter mattered. The fact that Christmas Eve created a moment of hesitation in some people mattered.

But Ritter’s role matters because he made a sequence of choices when many would have chosen speed:

he questioned ambiguous paperwork

he prioritized warmth and stability over intimidation

he created documentation to prevent disappearance

he redirected the transfer to a safer, trackable facility

he absorbed personal risk by becoming the “responsible” name on the file

That’s what courage often looks like inside bureaucratic war: not loud resistance, but refusing to let human beings fall through administrative cracks.

The Moral That Refuses to Be Simple

This story is not offered to rewrite history into a comfortable tale.

The war in Europe was a catastrophe with enormous suffering, and no single act of restraint cancels that. A German officer doing one humane thing does not transform the system he served into a humane system.

But the story matters because it exposes a difficult truth:

Even in the worst machinery, individuals still make decisions.

And sometimes those decisions determine whether teenagers live long enough to become old men who can tell the story.

On Christmas Eve 1944, 300 British teenage prisoners expected the night to swallow them.

Instead, a German officer used the quiet weapons of restraint—keys, forms, stamps, and a refusal to rush—to keep them visible.

In war, visibility can be survival.

And that is why, long after the snow melted and the gate rusted away, the men who lived through it remembered that night not as a miracle of emotion, but as a miracle of procedure:

A locked gate.

A destroyed transfer sheet.

Warm water before questions.

And a convoy that moved in daylight, on paper, to a place where their names could not be easily erased.

News

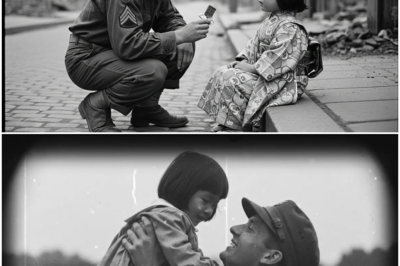

He Found a Silent Little Girl in Tokyo’s Ashes—Then an American Soldier Broke Every Rule, Signed One Hidden Paper at Midnight, and “Adopted” Her Before Dawn, Forcing a Secret Search for Her Real Name That Could Change Two Nations’ Story Forever

He Found a Silent Little Girl in Tokyo’s Ashes—Then an American Soldier Broke Every Rule, Signed One Hidden Paper at…

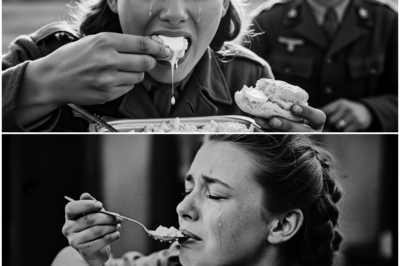

“‘Best Food of My Life!’—German Women POWs Expected Cold Rations, But a Texas Pitmaster Rolled Up to the Barracks, Lit a Secret Smoker, and Served BBQ So Tender It Sparked Tears, Rumors, and One Letter Home that changed everything overnight”

“‘Best Food of My Life!’—German Women POWs Expected Cold Rations, But a Texas Pitmaster Rolled Up to the Barracks, Lit…

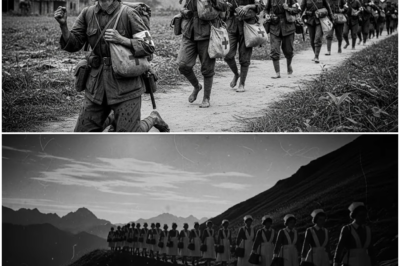

They Thought the Winter Would Finish Them in the Snow—Until U.S. Soldiers Formed a Human Chain, Lifted the Weakest onto Their Backs, and Carried Them for Miles Through Whiteout Darkness, Revealing a Quiet Order That Changed Who Survived by dawn

They Thought the Winter Would Finish Them in the Snow—Until U.S. Soldiers Formed a Human Chain, Lifted the Weakest onto…

511 Men Were Locked Behind Barbed Wire as a ‘No-Witnesses’ Order Spread—Until Rangers Slipped Through the Night, Cut the Power, and Unleashed a One-Minute Miracle That Saved a Camp and Exposed Who Lit the Fuse before dawn could erase them

511 Men Were Locked Behind Barbed Wire as a ‘No-Witnesses’ Order Spread—Until Rangers Slipped Through the Night, Cut the Power,…

They Expected Interrogations and Shame—But the First Thing Guards Handed 87 Italian Women Partisans Was Soap: A Quiet “Wash First” Order, a Locked Ledger, and a Missing Photograph That Explained Why They All Collapsed at Once inside the intake hall

They Expected Interrogations and Shame—But the First Thing Guards Handed 87 Italian Women Partisans Was Soap: A Quiet “Wash First”…

They Vanished Behind Enemy Lines for Two Years—Then a Chinese Nurse Smuggled a Blood-Stained Map Inside a Bandage Roll, Triggered a Midnight River Escape, and Returned Home With a Secret Ledger That Named a Traitor Nobody Dared Question Until Now

They Vanished Behind Enemy Lines for Two Years—Then a Chinese Nurse Smuggled a Blood-Stained Map Inside a Bandage Roll, Triggered…

End of content

No more pages to load