At Sunrise They Braced for Gunfire—But U.S. Troops Rolled In With Hot Bread, Canned Meat, and Blankets, Exposing a Secret “Feed-First” Order That Silenced a Village, Shamed a Local Boss, and Changed Who Lived to Tell It

The sunrise looked wrong.

Not because it wasn’t beautiful—sometimes the sky insists on beauty even when the ground is torn apart—but because the village had learned to associate dawn with danger. In the months before that morning, daylight didn’t mean safety. It meant visibility. It meant patrols. It meant trucks. It meant decisions made by strangers with authority.

So when the first band of light touched the rooftops, the people of Kleinwald did what they had trained themselves to do: they became quiet.

Doors stayed closed. Curtains stayed tight. Children were kept inside. Men stood in shadowed hallways, listening. Women moved through kitchens without lighting fires that might draw attention.

Even the dogs seemed to understand. They didn’t bark the way they used to. They watched.

The rumor in the village had been spreading for days—half information, half terror, carried on the backs of travelers and the whispers of people who had already seen too much.

“The Americans are coming,” someone said.

“They don’t take chances,” someone else replied.

“They’ll punish anyone they think helped the wrong side.”

In war, rumors become maps. They tell people where not to stand, what not to say, how to breathe without being heard.

So that morning, the villagers expected the worst.

They expected shouting.

They expected the sharp, fast language of commands.

They expected the crack of gunfire as “warning” became “message.”

They expected bullets.

Instead, they heard… engines.

Not one. Several.

And then, unbelievably, the sound of metal lids clinking and paper sacks being dropped gently onto wooden tables.

Food.

The Village That Had Learned to Fear Its Own Morning

Kleinwald was not famous. It wasn’t on postcards. It had no major military value. It was the kind of place history often forgets—small streets, stone houses, a church whose bell had been silent too often, fields that still tried to grow crops even when the world demanded war.

But Kleinwald had been trapped inside the logic of the front. Forces moved through, then moved on. Orders came, then changed. Young men were taken. Supplies were requisitioned. Houses were searched. People learned to cooperate with whoever stood at their door, not because cooperation meant loyalty, but because refusal could mean consequences.

By the time the Americans approached, the village was exhausted in a way that didn’t look dramatic. It looked like thinner faces and quiet children. It looked like empty pantries and careful firewood use. It looked like people who no longer argued loudly because arguments cost energy.

What they feared most wasn’t a specific army.

It was unpredictability.

When the rules change every week, you stop trying to understand morality. You focus on survival.

And that morning, survival seemed likely to be tested again.

The First Truck

The first U.S. truck rolled into the main square slowly, like the driver was trying not to provoke panic.

The villagers watched through narrow gaps in curtains. A few older men stood behind a half-collapsed stone wall near the churchyard, not armed, just present—too proud to hide completely.

A second truck followed. Then a jeep.

The vehicles stopped with controlled spacing. Soldiers stepped down, scanning the area with alert eyes. Their movements were deliberate, not sloppy. They carried rifles, yes—but their rifles were not raised in the posture of immediate threat.

A young lieutenant—Lt. David Mercer, according to later accounts—walked to the center of the square and raised one hand, palm down, the universal signal for “easy.”

An interpreter stood beside him.

Mercer didn’t shout. He didn’t bark. He spoke in a firm voice that carried without aggression.

“We’re here to secure the area,” the interpreter translated. “No one needs to run. Stay calm.”

The village stayed silent anyway, because calm is not a switch you can flip when you’ve lived in fear for months.

Then Mercer said the sentence that made people blink.

“Food distribution starts now,” the interpreter announced. “Children and elderly first.”

For a moment, nobody moved.

Because it sounded like a trick.

Why They Expected Bullets

Later, people asked the villagers why they expected gunfire from Americans specifically. The answer wasn’t ideological. It was experiential.

They had learned that arriving armies sometimes make examples. They had learned that civilians are often suspected of collaboration simply because they survived. They had learned that in the chaos of shifting fronts, misunderstandings can become tragedies quickly.

And they had heard stories—some true, some exaggerated—about villages punished for resisting or for hiding soldiers, about people being forced into lines and questioned harshly, about the way fear travels faster than facts.

So when the Americans came, the villagers prepared for the harshest interpretation.

They hid their radios. They hid photographs. They hid anything that could look like allegiance to the wrong side.

They were ready to be accused of things they didn’t fully understand.

Instead, they were being offered bread.

The “Feed-First” Order

The lieutenant’s unit had received a directive that most villagers would never see, and most soldiers would never describe in grand terms because it sounded too simple to be important:

Stabilize civilians by feeding them before questioning them.

It wasn’t a sentimental policy. It was a practical one. Hungry, terrified people panic. Panic creates chaos. Chaos creates accidents. Accidents create deaths.

So in places where civilians were depleted and tense, officers were encouraged—when supplies allowed—to lead with food and warmth.

It was a tactic of de-escalation.

But to the villagers, it looked like mercy.

Because most of them hadn’t been treated with de-escalation by anyone for a long time.

The Table in the Square

Soldiers unfolded tables and set them near the church steps. They opened crates: canned meat, hard bread, dried milk packets, simple rations designed for portability. It wasn’t a feast. It was war food. But it was food that existed in quantity—enough to be shared, enough to be distributed deliberately.

One soldier handed a loaf to the interpreter, who held it up to show the crowd.

“Come,” he called in German. “Children first.”

A mother peeked out of her doorway, clutching her son’s hand.

She didn’t approach.

She just stared.

The boy, thin and curious, tugged at her sleeve. “Mama,” he whispered, “bread.”

The mother’s face tightened. Tears gathered—not from joy, but from the unbearable tension of deciding whether hope was safe.

The interpreter stepped toward her slowly, leaving space, not rushing.

“It’s okay,” he said gently. “He can come.”

The mother hesitated.

Then she took one step.

Then another.

She approached the table like it might explode.

A soldier placed bread into her hands without grabbing her, without forcing her to look up. Just a direct transfer—human to human.

The mother’s shoulders sagged.

She didn’t speak. She couldn’t.

She turned away quickly, as if staying too long might cause the kindness to be revoked.

Behind her, another mother stepped forward.

Then another.

And suddenly, the square began to fill—not with celebration, but with cautious movement. People emerging like animals from hiding, testing whether the world had changed.

The Moment People Started Crying

The first tears were quiet.

An old man—Herr Weiss, remembered by villagers—stood near the edge of the crowd, hands shaking. When the interpreter offered him a cup of hot liquid—coffee or soup, depending on the account—he refused at first, pride rising like a shield.

“I’m fine,” he said.

The interpreter didn’t argue. He simply waited, cup still extended.

Weiss’s eyes flicked to the steam. Then his face broke.

He took the cup with both hands and turned away, embarrassed.

And then he cried.

Not loud sobbing—just the kind of shaking, silent crying that happens when a person realizes they’ve been holding themselves upright with nothing but stubbornness.

A soldier nearby looked away deliberately, giving him privacy.

That detail mattered as much as the food.

Because privacy is part of dignity.

Soon, other villagers began crying too—women wiping their eyes with aprons, men staring at the ground too hard, children eating quickly as if afraid someone would take their bread away.

The tears weren’t only relief.

They were release.

Because the villagers had been prepared for impact. When the impact didn’t come, their bodies didn’t know what to do with the adrenaline.

So it came out as shaking and tears.

The Local Boss Who Was Suddenly Exposed

Kleinwald had its own internal power dynamics—every village does. During the war, local bosses often gained influence through control of supplies: who got extra flour, who got access to fuel, who received permits, who got protected.

In Kleinwald, a man known as Kurt Brandt—a local administrator—had positioned himself as a gatekeeper. Some villagers believed he had protected the town from worse. Others believed he had protected himself first.

When the Americans arrived with food, Brandt’s power changed instantly.

Because nothing weakens a small tyrant faster than a new supply chain.

Brandt appeared in the square wearing a clean coat that looked suspiciously clean compared to everyone else’s worn clothing. He tried to speak to the lieutenant, gesturing toward the distribution table as if it should be under his control.

The lieutenant listened briefly, then shook his head.

The interpreter translated the lieutenant’s response loudly enough for villagers to hear:

“No intermediaries. Direct distribution.”

Brandt’s jaw tightened.

The villagers watched, stunned. Many had never seen someone refuse Brandt openly.

Brandt tried again, voice rising. The lieutenant’s expression hardened.

“Step back,” he said.

Brandt stepped back.

It wasn’t a dramatic arrest or a public trial. It was something simpler: a visible shift in who held authority.

And the villagers understood immediately what it meant:

Brandt could no longer control who ate.

That was the “shame” the headline remembers—not humiliation for entertainment, but a collapse of the local power game that had thrived on scarcity.

The Questions That Came Later

After food distribution stabilized the square, the Americans did what occupying forces do: they began asking questions.

Not by rounding everyone up in a harsh line, at least not at first. The lieutenant spoke with village elders. The interpreter listened. Soldiers took notes. They asked about mines, about booby traps, about hidden weapons caches, about missing people.

But the order of events mattered.

By feeding the village first, the unit reduced panic. People were less likely to run. Less likely to lie out of pure fear. More likely to answer with clarity rather than frenzy.

Mercer’s unit didn’t do it because they wanted to be loved.

They did it because calm cooperation prevents casualties.

Still, the villagers experienced it as something else: the first time in a long time an armed arrival did not immediately treat them as guilty.

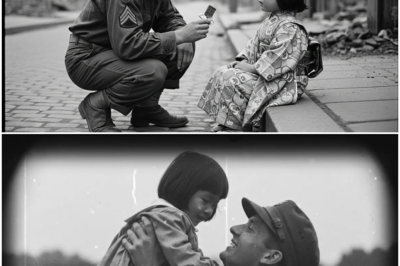

A Child’s Memory Becomes the Story’s Anchor

In later family retellings, the story often centers on one child.

A boy named Jakob, eight years old, who had been hiding behind his mother’s skirt when the trucks arrived. He had expected shouting. He had expected his mother to grip his shoulder hard and drag him away.

Instead, he saw a soldier kneel to his height and offer a piece of bread, palm open, no sudden movement.

Jakob hesitated.

The soldier smiled slightly—more with the eyes than with the mouth.

“Hungry?” the interpreter translated softly.

Jakob nodded.

The soldier placed the bread in Jakob’s hand.

Jakob later said the bread was warm, as if it had been guarded carefully on the journey. Whether it was truly warm or whether his memory warmed it doesn’t matter. What matters is what Jakob’s brain recorded:

The Americans came, and I ate.

For a child in a war-torn village, eating can be the most memorable form of safety.

The “Food First” Decision That Saved Lives

It’s easy to frame this as a feel-good story. But the deeper truth is more serious:

Leading with food may have prevented tragedy.

A frightened population can misread a soldier’s movement as threat. A soldier can misread a frightened man’s sudden motion as attack. In tense environments, misunderstandings can cascade.

By distributing food and keeping voices low, the Americans slowed the emotional tempo of the square. People’s hands were busy holding bread instead of clutching hidden objects. Children were eating instead of crying. Older people were sitting instead of standing rigid.

That shift reduced the chance of panic-driven escalation.

It didn’t erase danger. It reduced it.

And in wartime, reduction is often the difference between life and death.

The Night After: A Village Learns It Can Sleep Again

That evening, Kleinwald didn’t become joyful. It became exhausted in a new way—exhausted with relief, the kind that makes muscles finally loosen.

Families ate in their kitchens and listened for the familiar signs of night raids that didn’t come. Children fell asleep with full stomachs and woke briefly, confused by the unfamiliar sensation.

Older villagers whispered prayers. Some cried quietly in the dark.

And the village, for the first time in a long time, experienced something almost unbelievable:

A night where the loudest sound was not fear.

It was spoons against bowls.

What This Story Leaves Us With

“At sunrise they expected bullets… U.S. troops arrived with food instead” works as a dramatic headline because it captures the emotional reversal.

But the real story is about expectations—how civilians in war learn to anticipate harm, and how rare it is for armed power to choose restraint when restraint is possible.

This isn’t a claim that every unit in every place behaved the same way. War is uneven. Experiences vary. Some villages suffered terribly. Some endured harsh treatment. Some saw violence even at the end.

But in Kleinwald, on that specific morning, the American decision to lead with food created a different memory—one that survived precisely because it contradicted what the villagers had trained themselves to believe.

They expected bullets.

They received bread.

And for a village that had been living in fear of dawn, that single reversal became the moment the war—at least psychologically—began to end.

News

They Lined Up Expecting a Final Shot at Dawn—But U.S. Troops Led Them into a Warm Hall, Sat Them at Tables, and Served a Quiet Meal First, Exposing a Secret “No-Humiliation” Order That Changed Who Survived the night

They Lined Up Expecting a Final Shot at Dawn—But U.S. Troops Led Them into a Warm Hall, Sat Them at…

She Fell to Her Knees for One Crust of Bread—But the U.S. Soldier Opened His Rations, Led Her Behind a Ruined Church, and Uncovered a Hidden Ledger That Proved Who Was Hoarding Food, Triggering a Midnight Swap That Saved Her Child

She Fell to Her Knees for One Crust of Bread—But the U.S. Soldier Opened His Rations, Led Her Behind a…

She Thought Liberation Meant Freedom—Until Neighbors Dragged Her to the Town Square, Accused Her of Loving a German Soldier, and Shaved Her Head for Everyone to See, Forcing a Hidden Diary to Reveal Who Truly Betrayed Whom when silence broke

She Thought Liberation Meant Freedom—Until Neighbors Dragged Her to the Town Square, Accused Her of Loving a German Soldier, and…

They Braced for a Firing Squad at Dawn—But U.S. Guards Opened the Mess Hall, Lit a Hidden Grill, and Served German Women POWs Steak and BBQ, Unleashing Tears, a Secret “Feed-First” Order, and One Letter That Changed Everything Overnight

They Braced for a Firing Squad at Dawn—But U.S. Guards Opened the Mess Hall, Lit a Hidden Grill, and Served…

He Found a Silent Little Girl in Tokyo’s Ashes—Then an American Soldier Broke Every Rule, Signed One Hidden Paper at Midnight, and “Adopted” Her Before Dawn, Forcing a Secret Search for Her Real Name That Could Change Two Nations’ Story Forever

He Found a Silent Little Girl in Tokyo’s Ashes—Then an American Soldier Broke Every Rule, Signed One Hidden Paper at…

Christmas Eve 1944: 300 British Teen POWs Were Told They’d “Disappear” Before Dawn—Until One German Officer Locked the Gate, Destroyed the Transfer Orders, and Risked His Rank to Move Them to Safety, Leaving a Secret Note Unread for Decades Today

Christmas Eve 1944: 300 British Teen POWs Were Told They’d “Disappear” Before Dawn—Until One German Officer Locked the Gate, Destroyed…

End of content

No more pages to load