When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

The first rumor whispered through the barracks just after midnight.

Natsuko heard it in the dark, between the rasp of someone’s breathing and the soft, broken sobs of a woman three mats away.

“Tomorrow,” a voice breathed in Japanese, close enough that Natsuko felt warm air on her ear. “At dawn. They will line us up against the wall.”

She didn’t answer at first.

The night pressed in, thick and humid, the air sour with sweat and damp canvas. Far outside the makeshift compound, the jungle murmured: insects, distant waves, a wind that had finally remembered this island existed.

Natsuko stared up into the blackness above her straw pallet.

“You heard that from whom?” she whispered back.

“From Ishikawa,” the voice said. It belonged to Tomiko, a clerk from the logistics office back at the base hospital. “She heard an American guard say it to another. ‘Tomorrow morning, no more trouble with the Jap women.’ She’s sure she heard ‘shoot’ in there.”

The word settled between them.

Natsuko’s hands curled into fists.

They had been told, over and over, what would happen if they were captured alive. The instructors back in Japan, the angry men with armbands on the docks, the officers on the transport ships—they’d all painted the same picture.

Enemies took no prisoners.

Especially not Japanese.

Especially not women.

“Better to die by your own hand,” her training officer had said, eyes hard, “than to live as a plaything of the enemy.”

She had believed him.

In the end, she’d done something else.

Natsuko swallowed.

“At dawn?” she asked.

Tomiko nodded in the dark. Natsuko heard the rustle of fabric.

“They say it will be cleaner that way,” Tomiko whispered. “Quick.”

The strange thing, Natsuko thought, was that they spoke about it now with a kind of exhausted practicality. Not like a legend, or something dramatic from a newsreel. Just another task on tomorrow’s schedule, like checking bandages or counting supplies.

She realized she was too tired to be as terrified as she should be.

On the far side of the room, someone muttered a prayer. Someone else told her to be quiet. Mats rustled as women turned toward the wall, toward each other, toward nothing.

Natsuko shifted and felt the roughness of her borrowed uniform against her skin. The Americans had given them these clothes when they’d taken their own—sapphire blue nurse’s smock, name tag torn away, replaced with an armband marked with a black “P” and a number.

Prisoner.

She exhaled slowly.

If dawn meant a line of rifles and a sudden, sharp nothing, then this was her last night.

She found that her mind did not reach for the Emperor, or slogans, or speeches.

It reached for the small things: the bitter taste of over-steeped tea in the nurse’s station at Rabaul, her father’s hands stained with ink from the newspaper stand he’d run, the way her little sister’s laughter had filled their old wooden house like sunlight.

And lately, confusingly, it reached for an American face.

A young one, with tired eyes and a lopsided smile who’d handed her a canteen two days ago when she’d been stumbling from heat and hunger.

“You drink,” he’d said in clumsy Japanese, pointing to the water. “No… uh… no collapse. Okay?”

He’d grinned as if they were sharing a joke instead of occupying opposite sides of a war.

Natsuko squeezed her eyes shut.

By dawn, she told herself, he would probably be one of the men raising his rifle.

She turned onto her side, listening to the rustling, the whispered prayers, the quiet weeping. Tomiko’s hand found hers and squeezed.

“Natsuko,” Tomiko breathed, “if they ask whether we are afraid…”

“We are not,” Natsuko lied automatically. “We are daughters of Japan.”

Tomiko gave a tiny, shaky laugh.

“In that case,” she whispered, “I am a very unworthy daughter.”

Natsuko didn’t answer.

Instead, she stared toward where she knew the thin canvas wall stood, beyond which the Americans paced under a foreign flag.

Waiting for dawn.

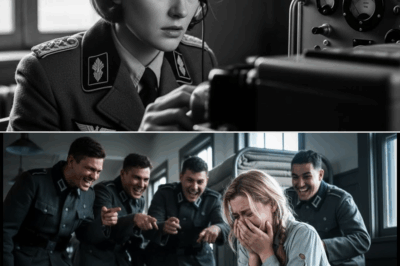

On the other side of that wall, an American captain leaned over a rickety table, arguing with his commanding officer for what felt like the hundredth time that night.

“Sir, we’re out of our minds if we think we can just treat them like crates in a warehouse,” Captain Jack Mercer said, jabbing a finger at the map between them. “They’re not supplies. They’re people. Seventy-eight of them. We have to decide what we’re doing with them before the sun comes up, not after.”

Major Whitaker rubbed his forehead.

His uniform was sweat-stained despite the lateness of the hour, collar askew, eyes red-rimmed from too many nights like this. The tent lantern threw harsh shadows across his face, making him look older than his thirty-eight years.

“We are treating them like people,” the major said, though the tired edge in his voice undercut the words. “We’re feeding them. We’ve given them shelter. We’re guarding them from our own hotheads. You want me to do what—open the gate and invite them to breakfast in the officers’ mess?”

Mercer didn’t flinch.

“Something like that, sir.”

Whitaker sat back, staring at him.

Outside, the camp murmured: crickets, distant surf, a truck backfiring somewhere up the road. In the compound, beyond the light, seventy-eight women lay awake and waited for a dawn that might be their last.

Whitaker tapped the butt of his pencil against the map.

“We’ve got wounded stacked on cots in a tent that reeks of gangrene,” he said. “We’ve got a supply ship two days late because some idiot admiral misread a schedule. I’ve got orders to be ready to move this whole outfit inland on twenty-four hours’ notice. And you’re in here at midnight arguing about… breakfast.”

Mercer’s jaw worked.

“With respect, sir, I’m arguing about what happens at dawn,” he said. “The men out there are scared. Those women in there are terrified. And if we don’t get ahead of what they think is going to happen, someone’s going to do something stupid.”

Whitaker’s eyes narrowed.

“Something like what?” he asked.

Mercer hesitated.

He thought about the conversation he’d overheard between two of his own men at the perimeter an hour earlier.

“You know what they say,” Corporal Pike had muttered, thumbing the bolt on his rifle. “Jap soldiers never surrender. These ones… they’re only alive ’cause we grabbed ’em too fast. Should’ve let ’em do their ‘honor’ thing. Now we got to babysit ’em and watch our backs.”

“Command’s just soft,” another had replied. “If they try anything, I say we line ’em up and settle it before it gets ugly.”

Mercer had stepped out of the shadows then, his voice low and sharp.

“You say that within my hearing again, Corporal, and I’ll have you breaking rocks until the war is over.”

Pike had snapped to attention, eyes wide, but the look on his face hadn’t been exactly repentant.

Now, in the tent, Mercer chose his words carefully.

“Something like somebody deciding to take ‘precautions’ we didn’t order,” he said. “Sir, half our guys have spent the last two years hearing that the enemy fights to the last man, that surrender is a trick. If those women so much as move wrong at dawn, some trigger-happy kid might decide he’s doing us all a favor.”

Whitaker’s shoulders sagged.

“And you think giving the prisoners breakfast will fix that?” he asked.

“I think,” Mercer said, “that if we treat those women like we plan on shooting them, that’s exactly what’s going to happen—whether we mean it to or not. If we treat them like human beings who are going to live through this day, my men will take their cue from that.”

The major was silent for a moment.

“Jack,” he said finally, using Mercer’s first name in the way he did only when he was very tired or very sincere, “these women… they’re not just any prisoners. Some of them worked on that airfield that cost us thirty guys last month. Some of them may have been marking targets, carrying messages. They’re the enemy. They’re not civilians we rounded up by mistake.”

“No, sir,” Mercer agreed. “They’re enemy personnel. And they surrendered. Unarmed. We put our flag over this place, that means the way we treat them says something about what that flag stands for.”

Whitaker looked at him.

“You think the flag stands for breakfast?” he asked dryly.

Mercer managed a thin smile.

“On a good day, sir, yeah. A hot meal and not getting shot at.”

Whitaker’s own mouth twitched.

He sat there, pencil motionless, eyes drifting toward the flap of the tent as if he could see through it to the row of sleeping forms on the other side of the compound fence.

He’d seen the fear in their faces when they’d been herded into that old warehouse and told to sit. He’d also seen something else—defiance, yes, but also a kind of brittle, brittle resignation.

He had been a young lieutenant back in North Africa when a German POW, shivering and exhausted, had looked at him and said in hesitant English, “You hold the gun, so you hold my life. Please hold it like a man, not like an animal.”

Whitaker still remembered that.

He sighed.

“Who’s on the perimeter tonight?” he asked.

“Pike’s squad on the south side, Reilly’s men on the east,” Mercer said. “If I tell them what the plan is before first light, they’ll follow it.”

Whitaker pinched the bridge of his nose.

“All right, Captain,” he said at last. “You win this one. You want to bring them breakfast, you bring them breakfast. You make damned sure your men understand that nobody fires a shot unless someone gives a direct order. And that order won’t be me.”

Mercer’s shoulders loosened.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Thank you.”

“Don’t thank me yet,” Whitaker muttered. “If anything goes sideways, I’m going to be the one explaining to division why we turned a prison detail into a church picnic.”

Mercer hesitated.

“There’s one more thing, sir,” he said.

“Oh for—what now?” Whitaker demanded.

Mercer took a breath.

“Some of our men have got it into their heads that the women are going to be executed at dawn,” he said. “Word’s gotten around inside the compound, too. That’s why they’re so jumpy. If we don’t knock that rumor on its backside hard, the breakfast isn’t going to mean much.”

Whitaker stared at him.

“Where in God’s name did they get that idea?” he asked.

“Somebody running his mouth with a bad sense of humor,” Mercer said. “Or a worse sense of honor.”

Whitaker swore under his breath.

“All right,” he said. “I’ll address the guard platoon myself. You talk to the interpreters. Make sure the women know we’re not planning to shoot them at dawn. Do it before the sun’s up.”

Mercer nodded and turned to go.

“Jack,” Whitaker said, just as he reached the flap. “If this turns into a mess…”

“I’ll own it, sir,” Mercer said quietly. “All of it.”

Whitaker’s eyes held his for a moment.

“See that you do,” he said. “Dismissed.”

Mercer stepped out into the humid night, the heavy air wrapping around him like wet cloth.

Somewhere beyond the fence, a woman who’d treated wounded men on the other side of the war lay awake, counting the hours until she believed she would die.

He had five hours to change her mind.

In the dim light of the barracks, Natsuko’s eyes burned from lack of sleep.

The night crept by in fits and starts: a guard’s footsteps outside, the clink of metal, someone shifting on a mat that creaked louder than it should have. Every noise felt like a rehearsal for the morning.

At some point, exhaustion dragged her under.

She dreamed of corridors—white, clean hospital corridors back in Japan—filled with the echoes of boots and the distant boom of propaganda speakers.

“…the enemy will show no mercy…”

“…honorable death is preferable to shame…”

In the dream, she was carrying a tray of medicine cups when a voice behind her said, “Natsuko.”

She turned.

It was her father, wearing the shopkeeper’s apron he’d always worn at home.

“Papa?” she said.

He looked at the tray in her hands, at the cups rattling with her shaking.

“You’ve spent this war tending to other people’s sons and brothers,” he said quietly. “You did your duty.”

She swallowed.

“I am still afraid,” she said. “Does that make me a coward?”

He smiled sadly.

“It makes you human,” he replied.

The corridor shook. The lights flickered. Somewhere, an air raid siren began to wail.

“Natsuko,” her father said again. “Wake up.”

She jerked, and the barracks snapped back into focus.

Tomiko’s hand was on her shoulder.

“Natsuko,” she whispered urgently. “Somebody’s coming. I think… I think it’s an interpreter.”

From the far end of the room, a voice called in careful, accented Japanese:

“Ladies, please. Everybody listen, please.”

Natsuko pushed herself up on one elbow.

A man in American khaki stood at the front of the barracks, just inside the door. He wore an armband with the letters “INT” and held a clipboard. Beside him was the young American she remembered—the one with the lopsided smile. His helmet was pushed back slightly on his head, and he looked even more tired than the last time she’d seen him.

The interpreter cleared his throat.

“You are all prisoners of war,” he said, reading from the paper in his hand. “The American army does not… does not shoot prisoners of war. You will not be killed at dawn.”

A ripple ran through the room.

Some women stiffened.

Others exhaled so sharply it sounded like a sob.

Ishikawa, the clerk who’d brought the rumor earlier, spoke up.

“Then why are the guards cleaning their rifles?” she demanded. “Why did they say there would be no more trouble from us after sunrise?”

The interpreter winced.

“I do not know what some stupid soldier said,” he replied. “But the official order: no harm to you. Guards prepare their rifles because this is war, and they are soldiers, but there will be no firing squad.”

An older woman near the back—the one everyone called “Aiko-sensei” because she’d been a teacher before the war—raised her hand like a schoolgirl.

“Why should we believe you?” she asked quietly. “We were told for years that your people have no honor.”

The interpreter glanced at the American beside him, then back at the room.

He spoke more slowly now, more carefully.

“In my family,” he said, “my father taught me that honor means how you treat people when you hold power over them. Today, my army holds power over you. If we lie, we lose honor. If we keep our word, we keep it.”

He looked around, meeting as many eyes as he could.

“The sun will rise,” he said. “You will be given food. Not bullets.”

The words settled over the women like a light rain over parched soil—welcome, but almost painful in their strangeness.

Natsuko felt her heart beating faster.

It hurt to hope.

The American beside the interpreter—Mercer—said something in English. The interpreter nodded.

“He says,” the interpreter added, “if anyone mistreats you, tell him. He will stop it.”

Someone snorted in disbelief.

Someone else whispered, “Can they do that? Stop their own men?”

Natsuko found herself staring at the young officer’s face.

He looked nothing like the monsters from the posters back home.

He just looked like a man who hadn’t slept in three days.

The interpreter stepped back.

“We will return at dawn,” he said. “Please be ready to come outside to eat.”

Then they were gone.

The door shut.

Silence hummed through the barracks, thick and buzzing.

Tomiko leaned close.

“Do you believe them?” she whispered.

Natsuko swallowed.

“I don’t know,” she said. “But if I only have a few hours more in this world, I would rather spend them imagining food than bullets.”

Tomiko’s laugh was half hysterical.

“I think I’ve forgotten what real food tastes like,” she said.

“Then we will find out,” Natsuko replied, a defiant note slipping into her voice before she could stop it. “Either in this life or wherever we go next.”

That earned her a scandalized glance from Aiko-sensei.

“Careful, Natsuko,” the older woman murmured. “The gods don’t like to be joked with.”

“Maybe they’re tired of being used in speeches,” Natsuko said quietly.

She lay back down, staring at the darkness, and felt something she hadn’t felt in days.

Not certainty.

Not trust.

Just… possibility.

It was almost more frightening than the alternative.

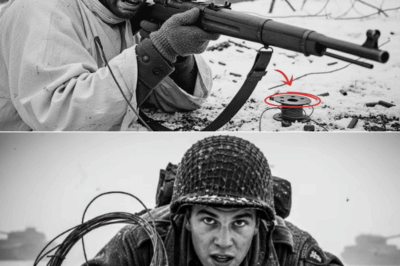

On the perimeter, Captain Mercer addressed the guards.

They stood in a loose semi-circle under the paling sky, helmets tilted back, faces lined with fatigue and sweat. Some were barely old enough to shave; others carried the set expression of men who had already seen too much.

“Listen up,” Mercer said. “There’s a rumor going around that the prisoners are going to be executed at dawn. That rumor is garbage.”

A murmur ran through the group.

Pike, arms crossed, frowned.

“Sir, nobody said—”

“I heard it myself, Corporal,” Mercer cut in. “We are not that kind of army. You see that flag?” He jerked his thumb toward the pole where the Stars and Stripes hung limp in the still air. “That flag doesn’t stand for lining prisoners up against a wall. Not women, not men, not anybody.”

“Sir,” another soldier spoke up, “they’re the enemy. You know what their guys did on the last island. Women, too. Some of ‘em were carrying grenades under their clothes. We lost people because we hesitated.”

Mercer nodded.

“I know,” he said. “Nobody is asking you to be stupid. You keep your eyes open. You keep your weapon ready. If somebody charges you with a weapon, you do what you have to do.”

He looked around the circle, making sure to meet Pike’s eyes.

“But unless that happens, nobody—and I mean nobody—touches a hair on their heads without an order. Nobody ‘takes initiative’ to ‘solve the problem.’ You get me?”

There were nods.

A few reluctant.

A few firm.

“You’ll be seeing those prisoners up close in a few minutes,” Mercer continued. “You’re going to watch them eat. You’re going to remember they’re human beings. They may have believed all kinds of things about us. Whatever they think, they’re about to find out that we don’t kill prisoners for sport.”

He paused.

“And if that doesn’t matter to you for their sake,” he said quietly, “let it matter to you for yours. Because someday, if you’re unlucky, you might be on the other end of that rifle. And you’ll want the man holding it to remember he’s a man.”

That landed.

Even Pike shifted his weight.

Mercer nodded once.

“Form up on your positions,” he said. “Breakfast detail in ten. Move.”

As they dispersed, Major Whitaker stepped out from the shadows near the back of the group.

“I should’ve been a preacher,” Mercer muttered under his breath.

“You’d have bored your congregation to death,” Whitaker said. But there was no heat in it.

“You meant that part about ‘for their sake or yours’?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” Mercer said.

“Well,” Whitaker replied, “let’s make sure nobody gets to find out which side of that equation they end up on.”

They walked toward the mess tent together.

The sky in the east was starting to lighten.

Dawn crept into the compound like a shy visitor.

The first light touched the tops of the palm trees beyond the fence, then slid down the trunks, then spilled over the packed dirt yard where a rough table had been set up.

Natsuko stood with the others near the barracks door, heart thumping.

The guards outside shifted positions.

There were more of them now, she noticed.

Rifles at the ready.

Faces set.

“If they lied,” Tomiko whispered, “this is the moment we’ll know.”

Natsuko nodded, throat too tight to speak.

The door opened.

The interpreter stood there again.

Behind him, Captain Mercer and two other Americans carried metal containers that steamed in the cool morning air.

The smell drifted in, unfamiliar but rich.

“Please come out,” the interpreter said. “Form a line. You will be given food. Then we will talk about… arrangements.”

His Japanese faltered slightly on the last word.

Aiko-sensei stepped forward first, spine straight as if she were walking into a classroom.

One by one, the women followed.

Natsuko stepped into the yard and blinked at the sudden brightness.

The sky above was washed in pink and gold. The flag on the pole—enemy flag, she reminded herself—stirred faintly in a breeze.

The guard line stood about twenty meters away, rifles held at a low ready. Their faces were younger than she’d expected.

Some looked away when the women appeared.

Others watched, wary.

The metal containers were set on the table.

A soldier with a ladle opened one.

The smell of hot food hit Natsuko like a physical blow.

It wasn’t rice.

It wasn’t miso.

But it was warm.

Mercer said something in English and the interpreter relayed it.

“We have porridge, some dried fruit, coffee,” he said. “We know this is not your usual food, but it is what we have. The cooks worked through the night to have enough.”

Natsuko stared as a tin plate was handed to Aiko-sensei, then to the woman behind her, then to Tomiko.

When her turn came, she stepped forward, hands trembling.

The American with the ladle—a freckled kid with a nose sunburned bright red—met her eyes for half a second.

“Good morning,” he said quietly, in heavily accented Japanese.

She almost laughed.

“What is good about it?” she asked before she could stop herself.

He shrugged, a ghost of a grin on his face.

“You are alive,” he said. “It is a start.”

He filled her plate.

Some kind of thick, creamy porridge.

A spoonful of dried fruit that looked like shriveled jewels.

A chunk of bread.

It was more food than she’d seen in one place in weeks.

She stepped aside, clutching the plate, and sank down on the packed earth with the others.

For a few seconds, nobody moved.

Then someone took a tentative bite.

Then another.

Some women began to eat as if they were afraid someone would snatch the food away. Others ate slowly, cautiously, as if the meal were a test.

Tomiko took a mouthful and made a face.

“It tastes like glue,” she muttered.

“It tastes like life,” Natsuko said, and shoveled in her own first bite.

It was bland.

And wonderful.

She swallowed too fast and had to cough.

Coffee came next in metal cups.

Bitter, dark, unfamiliar.

Aiko-sensei sniffed hers.

“It smells like burned beans,” she said.

“Don’t complain,” Tomiko told her. “If this is hell, at least they serve breakfast.”

Despite everything, a few women laughed.

The sound was thin and shaky—but it was laughter.

Captain Mercer watched from a few meters away, hands on his belt, gaze flicking between the prisoners and his own men.

He saw Pike, tense but not overtly hostile, standing near the gate.

He saw one of the younger guards watching a group of prisoners with something like confusion on his face—as if trying to match the women eating porridge with the enemy he’d trained to hate.

And he saw Major Whitaker walking toward him with a tight expression that said the first phase of this crazy idea had worked—but they were not out of the woods yet.

“You happy?” Whitaker asked under his breath.

Mercer didn’t take his eyes off the yard.

“Relieved,” he said. “Happy can wait.”

Whitaker grunted.

“Don’t get too comfortable,” he said. “Division just radioed. They want a status report on the prisoners. Intelligence is already sniffing around. They think some of these women might be useful.”

“Useful how?” Mercer asked.

“Interrogation,” Whitaker replied. “Intelligence, propaganda, you name it. The brass is suddenly very interested in Japanese women who can read, write, and count airplanes.”

Mercer’s jaw tightened.

“Sir, as long as ‘useful’ doesn’t mean ‘broken,’ we can talk,” he said. “If some interrogator comes down here thinking he can rough them up, we’re going to have a problem.”

Whitaker’s eyes flicked toward him.

“Is that a line in the sand, Captain?” he asked softly.

“Yes, sir,” Mercer said.

“What if the order comes from higher up?” Whitaker pressed. “What if someone with more stars than me decides these women are expendable?”

Mercer turned to face him.

“Then we’re going to have a very serious argument, sir,” he said.

Whitaker studied him.

“Oh, we’re already there,” he murmured.

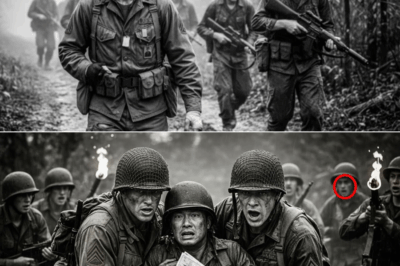

The argument arrived faster than either of them expected.

By mid-morning, the compound had taken on a strange rhythm.

The former prisoners—no longer quite sure what to call themselves—had been organized into small groups to help with basic tasks under guard: cleaning their own barracks, distributing extra blankets, tending to those too weak to move.

Natsuko found herself drafted, through a combination of language skill and remaining strength, to assist one of the American medical teams with triage.

It was absurd, she thought, to be standing under a foreign flag, wearing a prisoner’s armband, consulting in halting English with an American doctor over the best way to rehydrate one of her own countrywomen.

“Too fast, she will be sick,” Natsuko said, as the doctor prepared to hand over a full canteen. “Little. Slow.”

The doctor—a thin man with a wedding ring and worry lines—nodded.

“You’re a nurse?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said. “I was.”

He gave her a tired half-smile.

“You still are,” he said. “Help me with the next one.”

Across the yard, Captain Mercer watched that scene unfold while talking to the interpreter.

“They’re organized,” he said. “They’re used to taking orders. That could work for us or against us.”

The interpreter nodded.

“Aiko-sensei is helping keep order,” he replied. “They listen to her.”

“Good,” Mercer said. “The more they police themselves, the less my guys will feel jumpy.”

That was when the jeep rolled in.

Dust kicked up as the vehicle screeched to a stop near the command tent.

A tall officer climbed out—lean, sharp-faced, wearing the insignia of an intelligence major.

Mercer’s stomach sank.

He’d seen that look before.

Major Daniel Kerr strode across the yard with the air of a man arriving at a problem he’d already solved in his head.

“Whitaker,” he called, spotting the camp commander. “Heard you’ve got some interesting guests.”

Whitaker stepped forward.

“Kerr,” he said. “Didn’t expect to see you this far forward.”

“War’s moving fast,” Kerr replied. “So are we. I’ve got orders from division intelligence to debrief your prisoners. Especially the educated ones. We think some of them were clerks at that airfield command. Maybe even in signals.”

Mercer’s shoulders tightened.

“What does ‘debrief’ mean in this context, sir?” he asked.

Kerr’s gaze flicked to him, eyebrow lifting.

“And you are?”

“Captain Mercer. POW detail.”

“Ah,” Kerr said, as if spotting an interesting bug. “You must be the one who decided to turn this place into a breakfast buffet. Heard about that already.”

Whitaker’s jaw ticked.

“Captain Mercer has been following my orders,” he said. “You got a problem with the way I run my camp, Major, take it up with division.”

“Oh, I intend to,” Kerr said easily. “After I get what I need.”

He turned back to Mercer, eyes cool.

“To answer your question,” he said, “debrief means we talk to them. We ask questions. We get answers. We find out what units were here, what they were building, what codes they used. If they cooperate, maybe this goes easy. If they don’t…” He shrugged. “We have ways of encouraging cooperation.”

Mercer felt something cold settle in his chest.

“Sir,” he said carefully, “these women surrendered under the impression they’d be treated like POWs, not… suspects in a back alley.”

Kerr smiled without warmth.

“Captain, I’ve seen the reports from this sector,” he said. “You know what their side did on those last two islands. Prisoners machine-gunned, wounded bayoneted, nurses… well, let’s just say they didn’t fare well. You want me to lose sleep over making a few enemy auxiliaries a little uncomfortable so we can save our boys’ lives?”

Whitaker stepped between them.

“Nobody’s talking about ‘uncomfortable,’” he said. “And nobody is laying a finger on those prisoners without my approval. My orders from corps are to secure and hold, not to turn this place into your personal interrogation parlor.”

Kerr’s face hardened.

“Your orders from corps,” he said slowly, “do not override mine from division intelligence.”

He pulled a folded paper from his pocket and held it out.

Whitaker glanced at the letterhead, lips thinning.

The seal was genuine.

Intelligence had its own chain of command. Its own priorities.

Mercer felt the argument rising like a storm.

“Sir,” he said to Whitaker, “with respect, we both know what ‘ways of encouraging cooperation’ means in his line of work.”

Kerr turned on him.

“It means we do what it takes,” he snapped. “Do you think the enemy is out there playing by the grammar book? They’re starving our POWs, working them to death. We’ve got a camp full of potential gold mines and you two want to play schoolteacher and soup kitchen.”

Whitaker’s voice dropped.

“You lay a hand on those women in a way that violates the articles we signed,” he said, “and you won’t have to worry about the enemy. You’ll have to worry about me.”

Kerr laughed, but there was no humor in it.

“Oh, that’s rich,” he said. “You going to shoot me? Court martial me? Because I tried to get intel that might keep some of your boys alive?”

Mercer stepped closer.

He knew he was crossing a line.

He didn’t care.

“Sir,” he said to Kerr, “if we become the kind of army that thinks hurting prisoners is just another tool in the kit, then I’m not sure what we’re keeping our boys alive for.”

The air went very still.

Nearby, a group of guards paused in their work, watching.

On the far side of the yard, Natsuko glanced up from the woman she was helping, sensing the shift in mood even without understanding the words.

Whitaker’s eyes flashed.

“Captain,” he said sharply. “Stand down.”

Mercer clenched his jaw.

“Respectfully, sir,” he said, “I can’t stand down from this.”

Kerr’s voice rose.

“You can, and you will,” he snapped. “You don’t get to decide how this war is fought, Captain. Men like me do. Men who see the big picture.”

“The big picture?” Mercer shot back. “Or just the one in your report folder?”

Kerr took a step forward.

For a moment, Mercer thought he might actually throw a punch.

Whitaker stepped between them, palm outstretched.

“Enough,” he said, louder now. “This stops here.”

He looked from one to the other, jaw set.

“This is how it’s going to go,” he said. “Major Kerr will be allowed to speak with the prisoners. In daylight. In the open. With my interpreter present. Any questions will be asked in a language the prisoners understand. There will be no ‘methods’ that require closed doors or raised voices.”

Kerr’s mouth opened.

“Sir—”

“I am the ranking officer in this camp,” Whitaker said, voice like steel. “You want to challenge my authority, you take it up the line. Until then, you play by my rules.”

Kerr stared at him.

A muscle jumped in his cheek.

“You’re going to regret this,” he said quietly.

“Maybe,” Whitaker replied. “But I’ll regret it a hell of a lot less than standing over some dead girl’s body trying to explain to my conscience why I let you do what you wanted.”

For a heartbeat, it looked like the argument might tip into something worse.

Then Kerr stepped back.

“Fine,” he said. “We’ll do it your way—for now. But when somebody up there starts asking why our reports are thin and our casualties are high, I’ll make sure they know who decided to go easy on the enemy.”

He turned on his heel and stalked back toward his jeep.

The engine roared.

Dust billowed.

Then he was gone.

Whitaker let out a breath.

Mercer realized he’d been holding his own.

“You just made a powerful enemy, sir,” Mercer said quietly.

Whitaker shot him a sideways look.

“You think I did that for you?” he asked. “I did it because I sleep badly enough as it is.”

He paused.

“Captain,” he added, “if you ever pull that ‘respectfully I can’t stand down’ routine in front of another officer again, I’ll have you scraping latrines with a toothbrush for a month.”

“Yes, sir,” Mercer said.

Whitaker’s mouth twitched.

“But,” he added, “for the record, you picked the right hill to make a stand on.”

He walked away, barking at a nearby sergeant to double-check the gate locks.

Mercer stood there for a moment, heart still pounding.

On the other side of the yard, Natsuko watched the two Americans separate.

She turned back to the woman she was helping and dabbed the cracked lips with water-soaked cloth.

“Do you think they will kill us after all?” the woman whispered.

Natsuko shook her head slowly.

“The tall one…” she said, searching for words. “He looks like he is fighting someone. But not us.”

She looked down at her own hands.

They were trembling.

Tomiko appeared at her elbow.

“What happened?” she asked. “They looked ready to tear each other apart.”

Natsuko glanced toward Mercer.

He was talking now to the interpreter, gesturing toward the barracks, the gates, the sky.

“I don’t know exactly,” she said. “But I think it was about us.”

Tomiko made a face.

“I hope we were worth shouting over,” she muttered.

Natsuko thought of the dawn, of the porridge and the bread, of the bitter coffee and the strange American jokes that had slipped out despite the fear.

“I think,” she said slowly, “we might be.”

The days that followed were not easy.

The war did not stop at the compound fence.

Artillery still rumbled in the distance.

Planes still droned overhead.

Orders still arrived over the radio, some clear, some not.

Major Kerr returned twice, each time with a stack of questions and a tighter expression. Under Whitaker’s watchful eye, he interviewed prisoners through the interpreter, pushing, probing, occasionally snapping when answers were vague or unhelpful.

Natsuko found herself called in once, asked about supply routes, radio schedules, the exact layout of a base that no longer existed.

She answered what she could and kept silent when she felt she had to.

Kerr’s eyes bored into her.

“You know more than you’re saying,” he said at one point.

“Probably,” she replied.

The interpreter almost choked translating that.

Kerr looked as if he wanted to shout.

Instead, he exhaled sharply.

“This isn’t over,” he told Whitaker on his way out.

It was, though, for that camp.

Because the war was moving, and it pulled even people like Kerr along in its current.

Within a week, new orders came.

The women were to be transferred to a larger, more permanent POW facility inland.

Trucks were lined up.

Belongings—such as they were—were gathered.

Guards formed up in columns.

On the morning of departure, Natsuko stood in the yard with Tomiko and Aiko-sensei, clutching a small bundle of clothes and a tin cup that now felt like an anchor.

“Do you think it will be worse there?” Tomiko asked.

“Probably different,” Natsuko said.

Aiko-sensei smiled faintly.

“Different is not always worse,” she said. “Remember when we arrived here?”

They all did.

Back when the walls had seemed like the last thing they would ever see.

The interpreter arrived with Mercer.

“Trucks will take you to the new camp,” the interpreter said. “There will be more people there. Better facilities.”

“More fences?” someone asked.

“Yes,” he admitted. “But also more… organization.”

It didn’t sound like a promise.

It sounded like the best he could make of something none of them had chosen.

As the women began to climb into the trucks, one by one, Natsuko hesitated.

She turned toward Captain Mercer.

He stood a few paces away, arms crossed, watching the loading.

She stepped closer.

“Captain,” she said in English, the word awkward in her mouth.

He blinked, then nodded.

“Yes?” he said.

She struggled for the next part.

Her English was rusty, lifted from textbooks and overheard fragments.

“When we come here,” she said, haltingly, “we think we die at morning.”

He nodded slowly.

“I figured,” he said.

“You… change that,” she continued. “You bring… food. You fight…”

She made a small punching gesture, searching for the word.

“…argue,” he supplied.

“Yes. Argue,” she said. “For us. I want say…”

She paused.

Her heart hammered, ridiculous for something as simple as two words.

“Thank you,” she said.

He smiled, just a little.

“You’re welcome,” he said.

She hesitated again.

“In my country,” she said, “they say you have no honor.”

He winced.

“Yeah,” he said. “In my country, we’ve heard a few things about yours, too.”

She tilted her head.

“And now?” she asked.

He looked out over the yard—the guards, the trucks, the flag, the jungle beyond.

“I think,” he said slowly, “honor’s not a flag or a uniform. It’s what you do when somebody can’t fight back. That’s when it shows.”

She considered that.

“It is… difficult,” she said.

“Yeah,” he agreed. “Most worthwhile things are.”

A guard called out from the truck bed.

“Captain! We’re ready!”

Mercer nodded.

He looked back at Natsuko.

“Good luck,” he said.

She nodded once.

“Maybe… after war… we eat breakfast again,” she said, surprising herself.

He laughed.

“I’d like that,” he said. “We’ll try to find something better than porridge.”

She climbed into the truck.

The engine growled.

The convoy rolled out, leaving behind the little camp by the sea where, for a brief moment, the war had paused long enough for people on opposite sides to argue fiercely about whether mercy was weakness—or the one thing worth fighting over.

Years later, on a quiet morning in a different country, an older woman would stand at a kitchen stove, stirring oatmeal in a pot.

Her granddaughter, hair in tangled braids, would wrinkle her nose.

“Grandma, why do you always make this?” the child would complain. “It’s so boring.”

The woman—Natsuko Mercer now, though very few people knew she’d once been someone else—would smile.

“You know,” she would say, “once upon a time, this was the best thing I ever tasted.”

The child would roll her eyes.

“You always say that,” she would mutter.

Natsuko would gently tap her spoon against the rim of the pot.

“And it will always be true,” she would reply.

When the child ran off, chasing some newer thrill, Natsuko would open a drawer and take out an old, dented tin cup.

She’d turn it over in her hands, feeling the tiny dings and scratches.

On the bottom, faint but still visible after all those years, was a set of stamped letters:

U.S. ARMY.

She’d think of a dawn on an island far away.

Of fear that tasted like metal.

Of porridge that tasted like salvation.

Of men in foreign uniforms arguing in heated tones about what kind of army they wanted to be.

She would remember the young captain’s face as he’d stood between his own major and an intelligence officer, voice tight but unshaken.

And she’d remember the way the rumor of execution had broken, not with gunfire, but with the clatter of metal cups and the smell of hot food.

She’d set the tin cup back in the drawer and close it.

Somewhere, on the other side of the ocean, an old man who’d once been Captain Jack Mercer would sit on his porch, sipping coffee, and tell his grandson about the morning he learned that sometimes the bravest thing you could do in a war was to refuse to become the kind of man the enemy propaganda claimed you already were.

He’d talk about how the argument that day had been one of the most serious and tense of his career.

How he’d almost pushed it too far.

How his commanding officer had backed him when it counted.

And how, in the end, the thing he was proudest of in all his campaigns wasn’t a hill taken or a bridge held, but a simple, stubborn insistence that in a world gone mad, bringing breakfast instead of bullets could be an act of courage.

He wouldn’t know that on the far side of the Pacific, a woman who’d once been his enemy stirred oatmeal and thought the same thing.

War had tried very hard to make them monsters to each other.

For one fragile, stubborn morning, they’d refused.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell That Could Punch Through a U-Boat’s Pressure Hull and Send It Down With One Hit in the North Atlantic Night

They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell…

End of content

No more pages to load