When General George S. Patton Walked Into the Flaming Chaos of Europe’s Darkest Winter, Everyone Thought He’d Break—Instead He Turned Hell Into Momentum and Came Out Driving an Entire Continent Toward Freedom

On the morning George S. Patton first tasted what he would later call “hell,” the desert sky over Tunisia was clean and bright and utterly indifferent.

The air was sharp. The light was hard. The news was worse.

He stood on a low rise near Thala, boots grinding in the grit, binoculars pressed so tightly against his eyes they left red rings afterward. Down in the valley, American vehicles burned—half-tracks, tanks, trucks—scattered like toys a careless child had kicked and forgotten.

Smoke curled up in lazy, twisting columns.

Farther off, slender German tanks moved with practiced purpose, silhouettes crisp against the yellow-brown earth. Every so often, a flicker of light on one of their gun barrels was followed, seconds later, by another bloom of fire among the American wrecks.

Behind Patton, a young staff captain cleared his throat softly.

“Sir,” the captain said, “General Eisenhower’s last message said—”

“I know what Ike said,” Patton cut in. His voice was low, tight. “Read it again.”

The captain unfolded the flimsy, hands trembling just enough that the paper rustled audibly.

“EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY,” he read, “YOU ARE IN COMMAND OF II CORPS. STABILIZE THE SITUATION. STOP THE RETREAT. RESTORE CONFIDENCE. G. C. EISENHOWER.”

Patton let the glasses drop to his chest, hanging from their strap. For a few seconds he just looked at the message, as if the ink itself might explain how an army had come to bleed like this.

German forces had lashed out at Kasserine Pass—the first serious encounter between the Wehrmacht’s desert veterans and America’s green troops—and II Corps had buckled. Units had fallen back without orders. Road junctions had clogged with vehicles and men. Radios had choked with overlapping, panicked calls.

The men were brave enough. He could see that. bravery was not the issue.

Direction was.

“‘Stabilize the situation,’” Patton repeated under his breath. “As if we’re fixing a leaky roof.”

Behind him, engines idled. A jeep’s door slammed. Somewhere, a chaplain murmured over a blanket-covered shape.

He felt, for the first time in years, something like claustrophobia.

Not from the open desert.

From the size of the task.

He had wanted a real war. Now it had him by the lapels.

“All right,” he said aloud, as much to himself as to anyone else. “Let’s start walking.”

They began with helmets.

It seemed absurd, even to some of his own officers.

On his first full day in command of II Corps, Patton rode through shattered bivouacs in a dusty command car, standing in the back holding onto the windshield frame with one gloved hand.

Confusion was visible in everything: tents sagging, vehicles parked at odd angles, men wandering in undershirts and dog tags as if they’d just woken from a bad dream.

Patton’s face flushed.

He pointed with his riding crop.

“You, soldier!” he barked at a private carrying a mess tin. “Where’s your helmet?”

The man blinked, startled. “Sir, I left it by my—”

“On your head,” Patton snapped. “From now on, if it isn’t on your head, you might as well bury it, because I’ll have you out of this army before Rommel gets the chance to do it for me.”

He repeated the routine all morning.

At motor pools: “Park your damn trucks nose out, not sideways. You think this is a county fair?”

At field kitchens: “Clean this up. We’re not pigs. Men who live like pigs fight like pigs.”

At a tank maintenance area, he ran a finger along a greasy track.

“Who’s responsible for this vehicle?” he demanded.

A sergeant stepped forward. “I am, sir.”

“You keep it ready to move, Sergeant,” Patton said quietly. “The next time the Germans come, I want them to find engines running and guns loaded, not a pile of excuses.”

Behind him, one of his colonels muttered to another, “This is all well and good, but helmets and clean camps aren’t going to stop panzers.”

Patton heard him.

He turned.

“Colonel,” he said, “when you see a man who can’t button his shirt straight and can’t keep track of his own gear, you are looking at a man who will panic when shells land. Discipline is not decoration. It’s armor.”

The colonel grunted, chastened.

Patton climbed back into the car.

He knew this was only the start. The outward details mattered because they were symptoms of something deeper: a confusion of purpose.

The American army had come to North Africa with modern equipment and patriotic slogans and very little sense of how to turn those into a fighting instrument.

Patton walked into that chaos and, for the first time, felt just how close an army can get to falling apart.

If this was hell, he intended to rearrange it.

Within a week, II Corps looked different.

Not victorious.

Not yet.

But different.

Heretofore casual salutes snapped into place when Patton’s polished helmet appeared. Mess lines were organized. Vehicles were parked in rows. Radios followed protocols instead of panicked babble.

He walked into an operations tent one afternoon to find his staff huddled around a map of the El Guettar sector.

The atmosphere in the tent was thick—officers leaning over the table, voices overlapping, ash from cigarettes dusting the edges of the paper. The tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng—the argument had become serious and tight.

“We should counterattack now,” one brigadier insisted, jabbing a finger at a ridge. “Hit them before they regroup.”

“We’re not ready,” another said. “Our armor’s still mauled. If we go forward without proper artillery support, we’ll get chewed up again.”

“The men need to see we’re not just sitting,” a third officer added. “After Kasserine, they’re spooked. Giving ground again will break their spirit.”

Patton listened for a minute, letting the tension climb.

Then he slapped his riding crop on the table.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “we tried hasty attacks without proper coordination. The result is burning on that hillside.”

He jabbed at the map where he’d watched vehicles cook off days earlier.

“Rommel expects us to come charging,” he went on. “He thinks all Americans are the same. Brave, loud, disorganized. We’re going to give him a surprise. We’re going to sit and dig and make him come to us for a change.”

The brigadier who’d argued for immediate attack frowned.

“That sounds defensive, sir,” he said carefully. “I thought your philosophy was always to attack.”

Patton’s eyes flashed.

“This is an attack,” he said. “We’re attacking his expectations. His supply lines. His nerves. He doesn’t have infinite fuel. Every mile he drives, his tanks get thirstier. We’ll make them cross all those miles under our guns.”

He pointed at the map again.

“Put the armor hull-down here and here,” he ordered. “Anti-tank guns in these draws. Artillery pre-registered on every line of approach. And when he comes, don’t you fire one damn round until he’s close enough for his crews to see the whites of their own eyes in your scopes.”

Silence, then a slow nod from his G-3.

“It might work,” the operations officer said. “If our artillery can keep up.”

“It will work because we’ll make it work,” Patton said. “Now stop wringing your hands and start placing your batteries.”

As the officers bent over the map with renewed focus, Patton stepped back, feeling the strange calm that sometimes took him when decisions finally cut through argument.

He was, against his instincts, asking his men to wait in prepared positions instead of charging.

Walking into hell had taught him one thing already: hell rewards those who surprise it.

El Guettar did not turn into an American triumph overnight.

German armor still hit hard. American units still made mistakes. The desert still punished everyone equally.

But when Rommel’s spearheads drove into II Corps’s sector, they encountered something that had not been present at Kasserine: a coherent plan.

Tanks dug in on reverse slopes spat fire, then pulled back in controlled bounds. Artillery batteries shifted fire with surprising speed. Infantry stayed in their foxholes and fought instead of scattering.

Afterward, reading the captured German reports, Patton saw words like “stubborn” and “well-coordinated” used to describe his once-shaken command.

He allowed himself a brief smile.

“One step out of hell,” he murmured.

He didn’t believe in progress as a straight line. He believed in it as a series of fights—some external, some internal.

The external ones left marks on the earth.

The internal ones left marks on men.

Sicily was another kind of hell.

Not in the sense of collapse.

In the sense of hunger.

Not for food—though the supply situation was often tight.

For speed. For the next objective. For the thing just beyond reach.

The invasion itself went well enough. Patton led Seventh Army ashore in July 1943 on the island’s southern shore. The landings were less messy than North Africa. The Americans were learning.

But the plan, as drawn in Allied headquarters, offended him.

“Montgomery drives up the east coast to Messina,” Bradley explained, tracing the route. “We protect his flank, clear the west, and secure his supply lines.”

“So we’re the bridesmaid,” Patton said flatly. “Hold his bouquet while he marries the headline.”

Bradley shrugged. “That’s the deal.”

Patton stared at the map.

He saw ports. Roads. Towns whose names meant little to most generals but much to a man who loved movement: Palermo. Enna. San Stefano.

He saw opportunities.

“We can do both,” he said finally. “Protect his flank—and take the island from the west.”

The argument that followed with higher command was sharp-edged.

“You’re to defend,” Alexander’s staff signaled. “Not to conduct independent operations toward Palermo.”

Patton replied: “Defense in depth requires offensive action. Enemy will be more occupied with our threat to his rear than with static lines on a paper flank.”

Montgomery, reading copies of those messages, shook his head.

“He’ll overextend,” Monty told his own staff. “He’ll make a spectacle of himself and then blame us when he stubs his toe.”

Patton took Palermo in ten days.

Then he swung east, hugging the north coast, taking town after town with a mix of armored thrusts and infantry outflanking the coastal road.

His men cursed the dust, the heat, the stubborn German and Italian rear guards who fought for every hill and every stone house.

Patton cursed the mines, the bottlenecks, and any officer whose unit was not exactly where he’d ordered it to be when he’d ordered it.

In Messina, when he walked through the shattered streets and stood by the harbor where the last Axis units had slipped away across the strait to mainland Italy, he felt a flicker of the old, dangerous satisfaction:

I did it. We did it.

Then the headlines came: “Patton Beats Monty to Messina!” “Yanks Win Race!”

The applause curdled.

Not because he didn’t like winning.

Because he knew, with the slight sick feeling of a man who sees a truth just behind a triumph, that too many people would remember the race and forget the price.

They would forget the hills taken one bloody yard at a time, the men who never saw the inside of Messina because a mortar shell or machine-gun bullet had written “full stop” on their stories at Gela or Troina.

He walked into that city and heard cheers.

He also heard, in the back of his mind, a quieter voice:

Careful, George. Hell has more than one shape.

The shape it took next nearly burned him.

The incident in the hospital at Nicosia—slapping a soldier who, in Patton’s narrow, unyielding view, had no business calling himself sick when others bled—spread through the ranks like a cold wind.

The first time, there was outrage and confusion.

The second time, when it happened again with another soldier, there was shock.

Eisenhower’s cable arrived soon after.

It did not mince words.

“YOUR BEHAVIOR TOWARD HOSPITALIZED SOLDIERS IS UNACCEPTABLE. IT JEOPARDIZES PUBLIC SUPPORT AND MORALE. YOU WILL APOLOGIZE. YOU WILL CORRECT THIS. FURTHER INCIDENTS WILL END YOUR COMMAND.”

Patton sat alone in his tent after reading it, the paper trembling slightly in his hand.

He knew, in that moment, that he had done what enemy shells had not yet managed.

He had wounded himself.

He’d walked into hell that day not in the desert, but in a white tent lined with cots.

He’d seen fear and weakness where there were only wounds he did not yet understand.

He had been wrong.

That truth sat with him like a stone.

When he walked into the hospital days later to apologize, boots ringing on the boards, he felt something he did not like to name.

The men watched him with a mix of anger and shame and hope.

He stood by the first soldier’s bed.

“I was wrong,” he said. “I misjudged you. I did you an injustice. I’m sorry.”

No speech. No deflection.

Just that.

He repeated the ritual beds down the line.

The newspapers would later skewer him; some politicians would sniff that his temperament was unfit.

He took the blows with his teeth clenched.

The men in the wards respected the apology more than the headlines.

When he walked back out into the Sicilian sun, he had no illusions.

His halo—if he’d ever truly had one—was gone.

He was tarnished metal now.

But metal is forged in fire.

Hell had marked him.

He would bear that mark into his next war.

That war reached him in England in 1944, not with explosions, but with absence.

He arrived to find no field command waiting.

No units. No front-line army.

Just a role: commander of a phantom.

First U.S. Army Group. FUSAG. A formation that barely existed except in the minds of German intelligence and the files of Allied deception officers.

His staff car rolled past fields of rubber tanks and dummy artillery. His boots trod past tents filled more with rumor than with men.

He wrote in his diary at the end of May:

“To be a general without an army is a peculiar kind of hell. My name moves divisions I do not command and fixes on a map an army that does not exist.”

Yet, when he looked at the intelligence summaries—the ULTRA intercepts, the reports from double agents like GARBO—he saw something uncanny:

The Germans believed.

They believed Patton was in Kent, poised to strike at Calais.

They believed Normandy might be a feint.

They held their Fifteenth Army in the Pas-de-Calais region for weeks after D-Day, waiting for a blow that never fell.

Those divisions did not march against Omaha or Utah. They sat, and fumed, and sent plaintive signals complaining of Allied air attack and lack of gasoline.

Patton, reading those intercepts, realized that his ghost war had real casualties for the enemy.

He was walking through a different kind of fire.

Not gunfire.

Misdirected fire.

He learned to live with it.

He learned, too, that being feared for what you might do can be as potent as being feared for what you have done.

When the word finally came in late July that Third Army would be activated and unleashed in France, he felt the iron gate swing open.

The hell of stillness ended.

The hell of motion began.

Normandy after the breakout looked, from the air, like the underside of a defeated god’s skin: pocked, torn, streaked with roads.

Cobra’s bombardment had blown a hole in the German front near Saint-Lô.

Bradley pointed at the gap and said, “That’s your door, George. Don’t break the frame on your way through.”

Patton grinned.

“I won’t break it,” he said. “I’ll widen it.”

Third Army rolled.

They pounded south through Avranches, then fanned out like a hand opening: one finger toward Brittany, one toward Le Mans, one toward the Seine.

In the fields and towns and narrow lanes of western France, Patton’s tanks found a new landscape of hell: hedgerows, villages fought over house by house, ambushes at crossroads, stubborn German rear guards with Panzerfausts and 88s.

He drove his men hard.

He drove his staff harder.

At one meeting in a chateau-turned-headquarters near Laval, the air in the map room was thick enough to chew.

G-4 officers protested that fuel stocks couldn’t keep up.

G-3 warned that the infantry was falling behind the armor.

Engineers waved lists of blown bridges and cratered roads.

The tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng. Voices rose. Fists thumped tables.

Patton listened for a while, then stood.

“We have been in hell before,” he told them. “Kasserine was hell. Sicily’s mountains were hell. This—” he jabbed at the map “—is opportunity.”

He looked at his logistics officer.

“You tell me we’re short of fuel,” he said. “Fine. Whose fuel is being wasted guarding sectors where nothing is happening? Move it. Take it. Logistics is just another form of combat. Beat the other man to the pump.”

He turned to the infantry liaison.

“You tell me the doughboys are tired,” he said. “Of course they’re tired. They’ve been fighting since June. But they will be more tired if they are still here in December. The faster we move now, the sooner they rest—or at least die on their feet instead of rotting in some winter hole.”

It was harsh.

Harshness was his second language.

“Gentlemen,” he concluded, “if you ever find yourself wondering whether we should stop because it’s hard, ask yourself this: Would the Germans stop? They didn’t when they were winning. Why in God’s name would we when we are?”

The room’s energy shifted.

The arguments resolved into plans.

Fuel convoys were rerouted.

Bridges were prioritized.

Third Army slipped through the gaps and rolled east.

French civilians cheered themselves hoarse in town after town as the stars on Sherman tanks appeared at the end of their streets.

To those civilians, Patton’s army was not hell.

It was the end of it.

And yet, hell was patient.

It waited in Lorraine.

The autumn rains turned that region into a slog so miserable even Patton’s optimism cracked along the edges.

Mud swallowed tanks.

Fog grounded planes.

The German army, though battered, knew the ground well and used it.

“Butcher’s bill is going up,” one of his division commanders said grimly as they stood under a dripping tree, rain pecking at their helmets.

“Then we adjust the menu,” Patton shot back. “No more charging villages head-on without proper artillery and infantry coordination. Practice what we preach. Make the Germans pay in delay instead of blood when we can.”

In the evenings, in chilly interrogation rooms and smoky billets, Patton’s officers gathered around tables and tore apart not German tactics, but their own.

Why had this battalion driven straight into an anti-tank nest instead of flanking through the woods?

Why had those tanks run ahead of their infantry in that foggy village?

Sharp words flew. Careers hung in the balance. Pride was dented.

Patton insisted on it.

“If hell won’t teach you,” he said, “I will.”

He walked into those sessions knowing that every mistake unexamined was a mistake repeated.

If he ever was going to “lead Europe,” as some of the more breathless newspaper columnists liked to write, he knew it wouldn’t be with slogans.

It would be with corrections.

The hell he walked into next was white.

In December 1944, Patton’s army faced east, straining to break through the Siegfried Line and into the industrial heart of Germany.

He dreamed of Christmas on the Rhine.

Hitler dreamed of something else.

The German offensive in the Ardennes hit like a fist in a dark theater.

Snow fell. Fog settled. German tanks and infantry punched through the thinly held American lines in Belgium and Luxembourg, driving a bulge into the Allied front.

At SHAEF headquarters in Versailles, the map changed overnight.

So did Eisenhower’s expression.

Patton was summoned.

He arrived with the mud of Lorraine still on his boots.

The conference that followed has been written about, dramatized, simplified.

What matters is this: Patton walked into a room of tired, worried men and told them something they did not expect from an army commander whose formations were already committed.

“I can turn my army ninety degrees and attack north in two days,” he said, standing before the map.

Bradley frowned. “You’d need at least a week to prepare,” he objected.

“No,” Patton said.

Montgomery’s liaison raised an eyebrow. “With respect, General, moving an entire army in winter conditions is not like shifting a battalion on a sand table,” he said. “This is serious. The risks—”

The tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng once again. Men who had fought side by side for months now snapped at each other over axes and supply lines, over priorities and prestige.

Eisenhower listened.

Then he looked at Patton.

“You really think you can do it?” he asked.

“I don’t think, Ike,” Patton replied. “I know. I’ve had plans for a pivot on the shelf since we saw those German tank counts go up in the east. All I need is the word.”

Eisenhower weighed the options.

He could throw more units piecemeal into the bulge from the north and west, hoping to slow the Germans by frontal weight.

Or he could bet on this difficult, infuriating, brilliant man who stood before him and promised the impossible.

Ike made his choice.

“All right, George,” he said. “Turn your army. Rescue Bastogne. Then keep going.”

Patton snapped a salute.

“Hell,” he said later to his staff, “we’ve been waiting our whole lives to do something like this.”

Turning an army in that weather was a kind of hell all its own.

Snow choked the roads. Ice turned hills into traps. Drivers went white-knuckled. Engineers cursed as they spread sand and cut new paths.

Patton drove the roads himself, barking at MPs to clear intersections, at quartermasters to push gasoline, at mechanics to keep engines alive in the deep cold.

“Tell your men they’re not retreating, they’re advancing in a new direction,” he told one division commander.

They laughed, but they moved.

The prayer he had drafted with his chaplain for better weather—“Almighty God… grant us fair weather for battle”—made its way into pockets and helmets.

When the sky finally cleared and Allied aircraft roared in to tear at German columns, Patton’s tanks were already pressing toward the besieged 101st Airborne in Bastogne.

On December 26th, when the lead elements of the 4th Armored Division shook hands with paratroopers at the edge of the town, Patton allowed himself, for once, a visible grin.

“We’re through,” they signaled. “Corridor open.”

He walked into that hell—snow, shellbursts, men frozen and exhausted, enemies who refused to yield—and came out the other side with a phrase attached to him forever:

“The man who saved Bastogne.”

He hadn’t sent those airborne boys into that trap.

He hadn’t written their famous “Nuts” reply to the German surrender demand.

But he had refused to let them become a memorial instead of a fighting division.

If he led Europe in any sense, it was here: by refusing to abandon the surrounded, even when logic whispered that the cost of rescue might be too high.

When people later said Patton “led Europe,” what they usually meant was that his army had moved faster across it than anyone else’s, that his tanks had appeared in more towns, that his name had been on more lips from Metz to Mainz.

But sitting in a cold room in Luxembourg in the winter of 1945, boots perched on a crate, a half-smoked cigar between his fingers, Patton would have given a different definition.

“Leadership,” he told a group of young officers gathered for yet another grim little seminar, “is making your men do what they hate, to achieve what they love.”

He flicked ash on the floor.

“Sometimes,” he added, “that means walking into hell first, so they know it can be done.”

He’d met hell in different guises:

In the sight of burning tanks and running soldiers at Kasserine.

In the taste of shame in a Sicilian hospital tent.

In the sick feeling of watching other men go to France while he stood in Kent, commanding an army of air.

In the rain-soaked frustration of Lorraine.

In the frozen roads of the Ardennes.

He never pretended to enjoy those moments.

He pretended to be unbreakable in them, which is not the same thing.

What broke, if anything, was his vanity.

What hardened was his sense of what he could demand—from himself, from others, from a continent.

When Fourth Armored’s spearheads finally crossed the Rhine and rolled into the heart of Germany, Patton sat in a commandeered German office one evening staring at a map not of roads, but of boundaries.

Borders between zones of occupation.

Lines that would, everyone knew, shape Europe’s next wars as surely as this one had been shaped by the last.

“Sir,” a colonel asked, “do you ever think about what happens after we stop?”

“Every damn day,” Patton said. “But that’s somebody else’s fight. Ours was here.”

He tapped the rivers they’d crossed, the towns they’d taken, the bastions they’d cracked.

“You can’t lead a continent out of hell in one stride,” he said. “You do it bridge by bridge, field by field, town by town.”

He smiled faintly.

“And sometimes with tanks full of air,” he added. “Don’t forget the ghosts—they did their part.”

The colonel looked confused.

Patton waved it off.

“Never mind,” he said. “The point is: we walked through it. And we dragged Europe with us. That will have to be enough for now.”

After the war, after the accident that took him not on a battlefield but on a quiet road, people would argue about George Patton.

They still do.

They argue about his temper, his judgment, his politics.

They argue about whether he could have led better, or said less, or chosen his battles differently.

Those tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng, even in peacetime.

But for the men who followed him from Tunisia to the Rhine, and for the people in the towns where his tanks first appeared with white stars on their flanks, the memory is simpler.

He walked into hell—not once, but many times.

He did not walk alone.

He came out of each fire a little more scarred, a little more tempered.

And when it mattered most—when the maps in Allied headquarters were covered in red arrows and black doubts—he stepped up to the edge of the flame, looked at the men behind him, and said the one thing any leader of Europe, in any age, must be able to say:

“Follow me.”

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

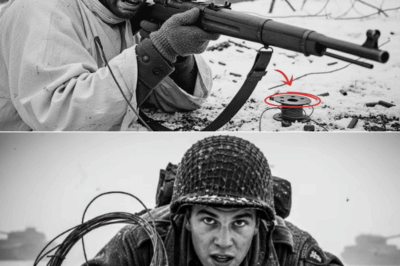

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load