When a Cocky Soldier Lashed Out at a Disabled Recruit in the Hallway and Went Pale as the Base General Stormed In, the Fight That Followed Rebuilt Their Entire Idea of Strength, Respect, and Command

Specialist Ryan Doyle didn’t wake up that morning planning to make the worst choice of his career.

He woke up to the usual: the blare of his phone alarm at 0500, the faint buzz of the barracks’ ancient fluorescent lights, and the symphony of complaints from Bravo Company’s second floor.

“Turn that off, Doyle!”

“Five more minutes!”

“Who stole my other boot?”

He rolled out of bed, bare feet hitting cold tile, and did a quick mental scan of the day.

PT. Formation. Weapons maintenance. An afternoon brief that would almost certainly be death-by-slide deck. Same old.

He brushed his teeth, pulled on his uniform, and checked his reflection in the tiny mirror someone had duct-taped to the inside of his locker.

Tan skin, dark hair cropped short, brown eyes that could look intimidating or bored depending on the day. He practiced the bored look, just to be sure.

He liked being the guy nobody worried about. Solid PT scores, good with his rifle, not enough ambition to be suspicious. He did his job. He stayed out of trouble.

Or at least, he had.

“Let’s go, hero,” his roommate, Specialist Cruz, said, tossing him a granola bar. “If we’re late again, Sergeant Mills will eat us for breakfast instead of the mystery eggs.”

“I’m not scared of Mills,” Doyle said automatically, stuffing the bar in his pocket. “I’m scared of the eggs.”

They stepped into the hallway, joining the flow of uniforms. Boots thudded, someone laughed too loud, someone else was already chugging an energy drink like it might save their soul.

That was when he saw her.

She was halfway down the hall, moving slower than the rest of the formation river. Shorter than most, dark hair in a tight bun, uniform pressed within an inch of regulation perfection.

And a brace running from her right knee down into her boot.

She walked with a slight hitch—more than a limp, less than a stagger. The kind of gait people either pretended not to notice or got weird about.

Doyle had heard there was a new recruit in Alpha Company. A prior-service re-enlist. Medical clearance had been a whole thing, rumor had it. She’d fought to come back after an accident. Now here she was, real, not just a story.

That should have been all he thought: huh, respect.

Instead, something prickled under his skin. He couldn’t have said what. Annoyance, maybe, at the way traffic bottlenecked behind her. The line slowed, people tried to go around, someone bumped into his shoulder.

He was tired. Hungry. Not in the mood to be late and get chewed out.

“Come on,” Cruz muttered behind him. “We doing a stroll or what?”

The recruit glanced back quickly, as if she could feel the pressure. She shifted closer to the wall to give people room.

Most soldiers flowed around her without comment. A couple shot her curious looks. One guy in the back snickered under his breath.

Doyle felt the bottleneck close in front of him, and something ugly flickered in his chest.

Say something, some petty part of his brain whispered. Move it along.

He stepped forward as he reached her, irritation spilling faster than his sense.

“Hey,” he snapped, louder than he meant to. “You planning on clearing the hall sometime this year, or are we just doing parade pace now?”

She turned her head.

Up close, her face was younger than he’d expected, mid-twenties maybe. Dark eyes, steady and alert. No hint of the apology he’d unconsciously expected.

“Sorry, Specialist,” she said, the word clipped but not weak. Her nametape read NGUYEN. Her rank: PFC. “I’m moving as fast as I can.”

“She’s fine, man,” Cruz muttered. “Chill.”

But Doyle’s temper had already found a target.

“As fast as you can?” he said. “We’ve got ten minutes to formation. You can’t just—”

He gestured, annoyed, and his boot clipped the back of her brace.

It wasn’t a full kick. Not the way he’d remember it later, sick to his stomach.

It was a frustrated, careless swing of a foot meant to send a message: Hurry up.

But the brace locked for just a second, her weight shifted, and the physics didn’t care about intent.

Her leg buckled.

She went down hard on one knee, hand slamming against the wall to catch herself. The metal of the brace scraped the tile with a sound that made Doyle’s teeth ache.

The hallway went instantly, horribly quiet.

Someone sucked in a breath. Someone else muttered, “Oh, hell no.”

Doyle froze.

He hadn’t meant—

“Hey!” Cruz snapped, shoving Doyle’s shoulder. “What the hell is wrong with you?”

PFC Nguyen’s knuckles were white where she gripped the wall. Her head dipped for a second, breath coming fast, the pain clearly sharp despite her silence. Then she pushed herself back up, using the wall and her good leg, and squared her shoulders.

She didn’t look at Doyle.

“Excuse me,” she said, her voice even but tight. “I don’t want to make anyone late.”

She started walking again, the hitch more pronounced now.

Heat flooded Doyle’s face. His stomach twisted.

“I didn’t—” he started.

Cruz’s voice cut through him like a blade.

“Don’t even,” he said. “You just kicked a disabled soldier in the leg. In front of everyone. You think ‘I didn’t mean to’ fixes that?”

The word disabled hit Doyle harder than the shove.

He opened his mouth, grasping for something—apology, excuse, anything—but before he could speak, a voice barked down the hall.

“What’s the hold-up?”

Sergeant Mills stomped into view, face already in a familiar scowl.

Then he saw Nguyen’s slow steps, the brace, the weird, charged silence, and his scowl sharpened.

“What happened?” Mills demanded.

No one answered.

Doyle felt every eye on him.

Mills followed the staring line, landing squarely on Doyle’s face.

“Specialist,” he said. “You want to explain why my hallway feels like a funeral home?”

Doyle’s mouth went dry.

“Nothing, Sergeant,” he said. “We’re just moving.”

It was the worst possible answer.

Mills’ gaze dropped to Nguyen’s brace, then zeroed in on the scuff on the back.

His nostrils flared.

“PFC Nguyen,” he said, voice cooling. “You good?”

“Yes, Sergeant,” she said, though she wasn’t. “Just lost my balance for a second.”

Mills’ eyes flicked back to Doyle.

“That right?” he asked. “She ‘just lost her balance’?”

Doyle hesitated.

This was the moment, some distant, clear part of his mind said. You tell the truth now or you become the guy who lies about kicking someone who already has to fight to walk.

He swallowed.

“Yes, Sergeant,” he heard himself say. “She just—”

Cruz exploded.

“Bull,” he snapped. “He clipped her brace. Saw it with my own eyes. So did half the hallway.”

Murmurs. A couple of people nodded, eyes hard.

Mills’ gaze could’ve melted steel.

“Doyle,” he said softly. “To my office. Now. Cruz, you too. Nguyen, get to formation. We’ll talk later.”

“Yes, Sergeant,” she said.

She started moving again, jaw clenched, and the flow of the hallway resumed, less noisy than usual.

Doyle followed Mills, stomach in knots, wishing he could rewind the last sixty seconds and choose any other words, any other steps.

He’d made a mistake. A bad one. He knew that.

But he didn’t yet know how serious it would become.

General Amelia Reyes wasn’t supposed to be on base that morning.

She was scheduled for a video conference with division staff miles away, followed by a briefing with some visiting legislators who wanted to take photos with “real soldiers” and talk about budgets they didn’t fully understand.

She hated missing drill days. There was something grounding about standing in front of her formation, feeling the collective breath of people who’d signed up to do hard things in uncomfortable places.

But the Army didn’t revolve around her preferences.

She was halfway through her second cup of coffee, watching a presentation slide about infrastructure funding, when her aide, Captain Larkin, slipped her a folded note.

URGENT – INCIDENT IN BARRACKS – DISABLED RECRUIT HARMED – ALPHA/BRAVO – DETAILS SKETCHY

Reyes felt the muscles in her jaw tighten.

She stood up.

“Ladies, gentlemen,” she said, cutting off the major on screen mid-sentence. “I’m afraid I have a situation on my installation. We’ll have to reschedule.”

The faces on the video call blinked, startled.

“General, we were just getting to—”

“You were just getting to the part where you tell me you need more money for the same plan as last year,” Reyes said. “You can email me the slides. I’ll respond with comments. Have a good day.”

She ended the call, ignoring the flicker of disapproval on one colonel’s face.

“Talk,” she said to Larkin, already moving.

Larkin fell into step beside her.

“Ma’am, initial report from Sergeant Mills says a specialist from Bravo physically struck a new private in Alpha Company in the hallway,” he said. “The private uses a brace on her right leg. The specialist ‘clipped’ it. She went down. It may have been intentional. Or reckless. We’re not sure yet.”

Reyes’ stomach dropped.

“How bad is she hurt?” she asked.

“Medics haven’t seen her,” Larkin said. “She insisted she was fine and went to formation. Mills pulled the specialist and one witness into his office. He’s waiting on guidance.”

Reyes’ eyes narrowed.

“Name?” she asked.

“The private is PFC Mai Nguyen,” Larkin said, glancing at his tablet. “Re-enlist. Prior service. Injury from a training accident two years ago. Fought hard to get back in. Just transferred here last week.”

Of course, Reyes thought. She remembered the file. The waivers. The medical board notes.

“And the specialist?” she asked.

“Ryan Doyle,” Larkin said. “Battalion knows him. Decent record. No prior incidents. Not a repeat problem on paper.”

“On paper,” Reyes repeated.

She changed course toward the barracks without slowing.

“Ma’am?” Larkin asked. “Do you want me to call JAG? We can let the company handle the Article 15 process. We don’t usually—”

“I am not ‘usually’,” Reyes said, the words sharp. “A soldier under my command put their boot on another soldier’s disability. That’s not just a discipline issue. That’s culture.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Larkin said, falling silent.

Reyes’ father had walked with a limp from the time she was six.

A training accident, they’d told her. An explosion. Shrapnel. Words she didn’t fully understand then, just that the man who’d once carried her on his shoulders now moved more slowly, had to plan his route around stairs, and sometimes stared at his leg like it had betrayed him.

She remembered the way some people had looked at him when he struggled with doors. Pity. Annoyance. Occasionally, resentment—as if his existence with a cane was an inconvenience.

She’d learned early how thin the line was between “hero” and “burden” in other people’s eyes.

Years later, when she’d joined the Army herself and climbed through the ranks, she’d promised herself any installation she led would be different.

She’d kept that promise. As much as one person could.

Today would test that.

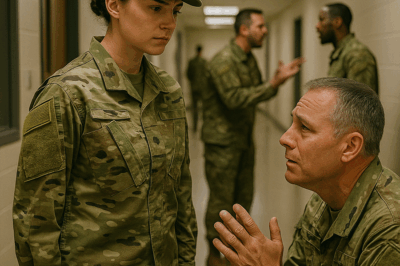

Sergeant Mills’ office felt too small for the weight in the air.

Doyle sat on a metal chair that wobbled every time he shifted. Cruz leaned against the wall, arms crossed, jaw clenched. Mills sat behind his desk, hands folded, eyes icy.

“How long have you been in my army, Specialist?” Mills asked Doyle.

“Three years, Sergeant,” Doyle said.

“And in three years,” Mills said, “did it ever once cross your mind that using your boot on another soldier is a great way to end your career?”

“I didn’t mean to kick her,” Doyle said. “I just—”

“Stop,” Mills said.

The word hit the room like a slap.

“You can tell yourself whatever story you want in your own head,” Mills said. “But you don’t get to sell it here. You raised your voice at a new private because she was slowing you down, then swung your foot and knocked her off balance. It doesn’t matter if you were aiming for her brace or the air near it. You used your body to make a point. That’s not leadership. That’s bullying.”

Doyle’s chest burned.

“I know I messed up,” he said. “I’m not saying I didn’t. I just— it wasn’t like I went in planning to—”

“Intent matters,” Mills said. “But impact matters more. Especially when there’s a thousand pounds of pressure behind a boot and one misstep between standing and the floor.”

He took a breath, visibly reining himself in.

“Regulation is clear,” he said. “Assault on another soldier is a serious offense. Doing it to someone with a documented medical condition? That’s… extra serious.”

Cruz spoke up, his tone sharp.

“She told him she was moving as fast as she could,” Cruz said. “He could’ve just gone around. Or shut up. Instead he—”

“Cruz,” Mills said. “I heard your initial statement. I appreciate you speaking up. You’re not in trouble. But I need to hear from Doyle now.”

He turned back to Doyle.

“Last chance to be completely honest, Specialist,” Mills said. “Because once this goes up the chain, any ‘I forgot to mention’ stuff is going to bite you.”

Doyle’s foot jiggled.

He could feel his heartbeat in his throat. Shame, fear, stubbornness—they all tangled.

He thought of his record. Clean. Boring, even. He thought of his mother’s face if she heard her son had been punished for kicking a disabled woman in uniform.

He thought of Nguyen’s face as she pushed herself back up, refusing to look at him. That hurt more than Mills’ anger.

“I was mad about being slowed down,” he said finally. The words tasted like sand. “I said something I shouldn’t. I swung my foot. I didn’t aim to knock her down, but I also… I didn’t care enough in that second if it would. I just wanted her to move.”

Silence.

Mills nodded once, slowly.

“That’s the first honest thing you’ve said,” he said. “It’s ugly. But it’s real.”

He opened his mouth to say more.

There was a knock on the door.

Mills frowned. “Come in.”

Captain Larkin opened the door, then stepped aside.

General Reyes filled the frame.

Every molecule of air in the room seemed to snap to attention.

“On your feet!” Mills barked.

Doyle shot up so fast his chair nearly tipped. Cruz did the same. Mills stood at rigid attention, eyes front.

“At ease,” Reyes said, stepping in. Her voice was calm, but not soft. “But not relaxed.”

They shifted to parade rest, shoulders still braced.

Reyes took in the scene in one sweep: the cramped office, Doyle’s pale face, Cruz’s clenched jaw, Mills’ guilt-ridden eyes.

“Sergeant Mills?” she said.

“Yes, ma’am,” he replied.

“Where is PFC Nguyen?” she asked.

“On the training field, ma’am,” he said. “She insisted she could still participate. I told the platoon sergeant to keep an eye on her. Medics are on standby.”

Reyes’ mouth tightened.

“We’ll deal with that in a minute,” she said. “Right now, I want to hear what happened. From all of you. One at a time.”

She nodded to Mills.

He gave a concise version. No embellishment, no smoothing. Just facts and what he’d been told.

Cruz went next. His story matched Mills’, with a few more colorful adjectives about Doyle’s behavior that he swallowed in front of the general.

Then it was Doyle’s turn.

He knew the script he could say. The one that would be safe-ish.

He also knew, on some bone-deep level, that she’d smell it.

So he told the truth. The whole, ugly version. How irritated he’d been. How he’d snapped. How he’d not cared, in that hot flash of temper, whether she stumbled. Only that she got out of his way.

When he finished, the room was quiet enough to hear the hallway clock ticking.

Reyes studied him.

“How old are you, Specialist?” she asked.

“Twenty-three, ma’am,” he said.

“How long have you been in the Army?”

“Three years, ma’am.”

“Have you ever had an injury?” she asked. “Broken bone, sprain, anything that made walking hard?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, surprised. “Sprained my ankle in basic. Hurt like hell.”

“And when you were limping around that training ground,” she said, “if someone had put their boot near your foot to ‘make a point’ about your speed, how would that have felt?”

His throat tightened.

“Bad, ma’am,” he said. Understatement didn’t begin to cover it.

“Bad?” she repeated. “Or humiliating? Infuriating? Maybe dangerous? Because a worse fall could have taken you out of training. Out of the Army.”

“Humiliating, ma’am,” he admitted. “And dangerous. Yes.”

She nodded.

“Yes,” she said. “Now imagine that sprain is a brace you’ll wear every day because of an injury you already fought to come back from. Imagine how many times you’ve had to prove, again and again, that you belong in uniform. Imagine the courage it takes to walk down a hallway where you know people are staring and come to formation anyway.”

Doyle swallowed hard.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “I didn’t… think about that.”

“No,” she said. “You thought about yourself. Your schedule. Your irritation. You made her body and her disability obstacles in your way instead of realities of a teammate’s life. That is not what we do here.”

She didn’t raise her voice.

She didn’t have to.

Doyle felt smaller than he ever had in his life.

“Ma’am, I’m sorry,” he said. “I know that doesn’t fix—”

She held up a hand.

“Hold that sentence,” she said. “Apologies have their place. But right now, this isn’t just about you and her. It’s about everyone watching. Because there were witnesses. And I guarantee you, every one of them is now wondering what this Army really does when a soldier uses their strength to shove down instead of lift up.”

She looked at Mills.

“You did the right thing pulling them,” she said. “But this is not staying in this office.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Mills said.

Reyes turned back to Doyle.

“I could send this straight to JAG,” she said. “You’d very likely be facing charges formally. You still might. But before I decide that, I’m going to do something else.”

Her eyes shifted to Cruz.

“Specialist Cruz,” she said. “You spoke up. In the hallway. And in here. That’s not easy, especially when the person in the wrong is your roommate. You did, however, call him out in front of everyone instead of pulling him aside earlier when you saw his temper.”

Cruz blinked.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “I— I didn’t know he was going to actually—”

“I know,” she said. “I’m not blaming you for his choice. I am reminding you that looking out for your battle buddy includes noticing when they’re about to do something stupid. Being brave isn’t just about shouting after the fact. It’s about intervening before harm happens, if you can.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, swallowing.

She nodded.

“Sergeant Mills,” she said. “Have PFC Nguyen pulled from the exercise. I want her seen by medical immediately. When that’s done, I want her, you, Cruz, and Doyle in the conference room next to my office at 1400. We’re going to talk about what happened. All of us.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Mills said. “Should I notify the company commander?”

“Already did,” Reyes said. “He’ll be there too.”

Doyle’s mind raced.

A conference with the general. The commander. The sergeant. Nguyen.

He’d never dreaded anything more.

Reyes looked at him one last time.

“Specialist Doyle,” she said. “Until further notice, you are restricted to barracks, mess, duty, and appointments. No gym privileges, no pass, no extracurriculars. We’ll discuss formal consequences later. Between now and 1400, I suggest you think very carefully about the soldier you want to be—and whether that soldier has enough courage to face the person you hurt without excuses.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he whispered.

She left without another word.

When the door clicked shut, Mills exhaled.

“Well,” he said. “You heard the general. Get your heads straight. This just went way above my pay grade.”

No one argued.

The medical exam found no new structural damage to Nguyen’s leg.

“Brace did its job,” the physician’s assistant said, rolling up her pant leg with practiced efficiency. “Ligaments look okay. Bruising, though. And strain. I want you off it as much as possible for a few days. You can still do upper body and seated drills if you insist on being ridiculous.”

Nguyen managed a small smile.

“Copy that, ma’am,” she said. “Ridiculous with conditions.”

When she stepped carefully into the hallway outside the clinic, General Reyes was leaning against the wall, arms folded.

“PFC,” Reyes said.

Nguyen straightened instinctively. “Ma’am.”

“At ease,” Reyes said. “How’s the leg?”

“Hurts, ma’am,” Nguyen said honestly. “But nothing’s broken. Again.”

“Good,” Reyes said. Her gaze softened slightly. “I read your file. You fought like hell to come back in. I remember your appeal.”

Nguyen’s cheeks warmed.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “I didn’t want my last memory in uniform to be a hospital ceiling.”

Reyes huffed a quiet breath that almost passed for a laugh.

“I understand that,” she said. “I also understand that having a brace in this environment comes with a thousand small battles, most of which the people around you never see.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Nguyen said.

“You didn’t report the incident,” Reyes said.

Nguyen swallowed.

“No, ma’am,” she said. “I didn’t want to be the ‘problem private’ on my second week. I figured I could handle it.”

“Handle being knocked down in a hallway by someone who outranks you?” Reyes asked. “You think that’s something you should have to ‘handle’ quietly?”

Nguyen looked down at the scuffed toe of her boot.

“I’ve had worse, ma’am,” she said softly. “People saying worse. I’m used to proving myself twice as hard.”

“Being used to something doesn’t make it right,” Reyes said.

Nguyen’s eyes flicked up.

“Ma’am, I don’t want him thrown out because of me,” she said quickly. “I just… I want him to understand it wasn’t okay. That I’m not—”

She broke off, searching.

“—a prop in whatever lesson he thinks he was teaching,” she finished.

Reyes nodded slowly.

“That’s fair,” she said. “At 1400, we’re going to have a conversation. Not another yelling match. A serious one. You deserve to be in the room where your experience isn’t talked about like a file. You up for that?”

Nguyen’s stomach twisted.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “I am.”

“Good,” Reyes said. “And PFC? This doesn’t make you ‘fragile.’ It makes you honest. That’s not weakness. It’s strength a lot of people never learn.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Nguyen said, voice barely above a whisper.

Reyes pushed off the wall.

“I’ll see you at 1400,” she said.

As the general walked away, Nguyen heard her grandmother’s voice in her head, in that lilting Vietnamese cadence from childhood arguments in cramped apartments.

Và cuộc tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng.

And the argument became serious.

Nguyen took a breath, shifted her weight on the brace, and headed back to the barracks to wait.

At 1355, Doyle stood outside the conference room, palms damp.

Through the frosted glass, he could see silhouettes—the commander, Captain Larkin, Sergeant Mills. An empty chair at the far end for the general.

His stomach lurched when Nguyen appeared at the end of the hall.

She walked a little slower than that morning, using the wall lightly for balance. Her face was calm, but her eyes flicked to him for the briefest second.

He saw the faint bruise on her cheek where it had met the wall. The newer discoloration around her knee.

Shame surged again, hot and choking.

He opened his mouth.

“PFC—” he started.

“Inside,” came a voice from behind him.

General Reyes.

He snapped to attention.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

They filed into the room.

The seating arrangement felt deliberate. Nguyen on one side of the long table, next to Sergeant Mills. Doyle opposite her, flanked by Cruz and Captain Larkin. The company commander at the head. Reyes at the far end.

A jug of water sat untouched in the center, like a prop.

Reyes waited until everyone was seated.

“Alright,” she said. “We’re here because something happened this morning that doesn’t align with who we say we are. We put a lot of words on posters about respect and inclusion. Those words don’t mean much if our behavior contradicts them.”

She glanced at Doyle.

“This is not a trial,” she said. “That may come later. This is a conversation. It will be uncomfortable. That’s the point.”

No one argued.

“PFC Nguyen,” Reyes said. “I want to start with you. If you’re willing, tell us what this morning felt like from your side. Not just what happened. What it meant to you.”

Nguyen’s fingers tightened in her lap.

She took a breath.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said.

She looked down the table, not at Doyle, but at a spot on the wood.

“I got up early,” she said. “I always do. It takes me a little longer to get ready. Shower, adjust the brace, check my leg for hotspots. It’s a habit. If I rush it, I pay later.”

She gave a tiny, humorless smile.

“I left the room early because I didn’t want to be ‘the slow one’ in the hallway,” she said. “But doors stick. Laces take longer. By the time I stepped out, everyone else was already moving.”

She squeezed her hands together.

“I could feel people behind me,” she said. “Impatient. I get it. I used to be fast. I know what it’s like to be stuck behind someone slower and feel trapped.”

Her gaze flicked up, briefly meeting Doyle’s.

“I hugged the wall to give space,” she continued. “People passed. Some kind of awkwardly, some without comment.”

Her voice flattened.

“Then I heard, ‘You planning on clearing the hall sometime this year?’” she said. “It was loud. Sharp. I turned and saw him.”

She nodded toward Doyle without saying his name.

“He outranks me,” she said. “He was bigger than me. And I knew everyone was watching. If I snapped back, I’d be ‘the mouthy private with a chip on her shoulder.’ If I ignored it, I’d be ‘the weak one who can’t take banter.’ So I did what we’re taught. I said, ‘Sorry, Specialist. I’m moving as fast as I can.’”

A small muscle twitched in her cheek.

“And then I felt his boot hit my brace,” she said. “It locked for a second. My knee gave out. I went down. It hurt. Physically, yes. But also… I can’t explain it. It felt like the thing I’ve been afraid of since I came back came true. That I’d be back on the floor, again, because of something I couldn’t fully control.”

She swallowed.

“I heard laughter stop,” she said. “I heard my brace scrape. I didn’t want to cry. I didn’t want to give anyone that kind of story. So I pushed up, said ‘excuse me,’ and kept walking. Because that’s what I do. I get up. I keep walking.”

She finally looked at Doyle.

“What it meant,” she said quietly, “was that someone in my own uniform saw my brace as an inconvenience, not as part of me. I was an obstacle, not a teammate.”

The room was utterly still.

Reyes nodded, expression grave.

“Thank you,” she said. “That took courage.”

She turned to Doyle.

“Specialist,” she said. “You heard that. Do you have anything to say before I ask you questions?”

Doyle’s throat felt too tight.

“Ma’am,” he said, voice hoarse. “I’m sorry.”

He looked at Nguyen.

“I’m sorry,” he said again, forcing the words out properly this time. “Not in the ‘oops, my bad’ way. In the ‘I was wrong’ way. I treated you like a speed bump. I didn’t think about your day, your leg, your fights. I thought about mine.”

Nguyen held his gaze, her own unreadable.

“I know ‘sorry’ doesn’t undo it,” he said. “If I were you, I wouldn’t want to hear it. But I mean it.”

Reyes let the moment hang, then intervened.

“Apologies are a start,” she said. “Now, Specialist Doyle, tell us why we should believe this is about more than you trying to save face.”

He swallowed.

“Because… I heard myself,” he said. “In my head. When I snapped. I sounded like the guys I used to hate in high school. The ones who shoved kids into lockers because they were too slow or too quiet or too different. I promised myself I’d never be that guy. But I was. Today.”

His shoulders sagged.

“I don’t want to be him,” he said. “Not once, not ever again.”

Silence stretched.

Captain Larkin spoke up.

“PFC Nguyen,” he said carefully. “Do you want to respond? You don’t have to.”

She took a breath, considering.

“I believe you mean it,” she said to Doyle. “That you’re sorry. I also believe you can’t just walk away from this thinking a few tears and a speech fixed it.”

He nodded quickly.

“I know,” he said. “I’m ready for whatever happens.”

“Good,” she said. “Because I’m not just worried about you. I’m worried about everyone who watched. The privates who saw a specialist kick someone with a brace and thought, even for a second, ‘Maybe that’s okay. Maybe that’s what power looks like.’”

Reyes’ eyes flashed approval.

“Exactly,” she said. “This is bigger than two people in a hallway. It’s about the story this unit tells itself about strength.”

She looked at Mills and the commander.

“Here’s what’s going to happen,” she said.

Everyone leaned in just a fraction.

“Specialist Doyle,” Reyes said, “you will receive an Article 15 for assaulting another soldier. Reduction in rank by one grade, forfeiture of half a month’s pay for two months, and extra duty. This will be on your record. Choices have consequences. This is one.”

Doyle’s stomach dropped, but he made himself nod.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “I understand.”

“You will also,” she continued, “complete a mandatory course on ethics and leadership, followed by three months of supervised mentorship with Sergeant Mills. During that time, you will not be in direct charge of any junior soldiers. You will earn that back, if you can, by proving this was a turning point, not a detour.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said again, a little stunned at the “if.”

She turned to Nguyen.

“PFC Nguyen,” she said. “You will not be required to work with Specialist Doyle if you don’t want to. You will not be asked to teach him how to be decent. That’s not your job. But if you’re willing, I would like your input on a training module we’re going to develop for this base about working with disabled soldiers—by which I mean soldiers with disabilities who are still soldiers.”

Nguyen blinked.

“Ma’am, I’m just a private,” she said.

“And you have lived experience neither I nor Mills nor your commander has,” Reyes said. “Rank gives authority. It doesn’t give omniscience. We need your perspective if we want to get this right.”

Nguyen hesitated, then nodded slowly.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said. “I can do that.”

Reyes looked around the table.

“Everyone in this room will attend that training,” she said. “Company leadership will attend. We will not have a culture where people have to hide their braces, their scars, their canes to be taken seriously. We will not, under my command, let ignorance masquerade as toughness.”

She let that sink in.

Then she added, more quietly, “My father walked with a cane for thirty years after he got hurt in uniform. I watched people treat him like a burden and a hero in the same day. I know which version made him want to never leave the house again. I will not have this base be that sidewalk.”

Doyle’s chest tightened.

“Yes, ma’am,” the commander said, voice sincere. “We’ll enforce it.”

“See that you do,” Reyes said.

She turned back to Doyle once more.

“One more thing,” she said. “You said earlier you didn’t think about what it meant to kick near someone’s brace. I believe that. I also believe you’re not going to fully understand until you put some sweat behind your words.”

She nodded toward Nguyen.

“PFC Nguyen has PT restrictions,” she said. “She can’t do distance running. But she can do a lot of other things. For the next month, Specialist—in addition to your normal duties—you will accompany her to every PT session she’s cleared for. Not as her watchdog. As her partner. You will run when she rows. You will plank when she planks. You will do the adaptive versions of exercises alongside her. You will see what it takes for her to stay in this uniform. Do you accept that?”

Doyle stared, startled.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “If she’s okay with that.”

All eyes turned to Nguyen.

She studied him for a long moment.

“Ma’am,” she said slowly. “I’m not interested in being anyone’s punishment. But if this is about him learning, and about other people seeing that learning, then… yes. I can handle that.”

Doyle exhaled, a mix of relief and dread.

“Thank you,” he said quietly.

She didn’t answer, but she gave a tiny, almost imperceptible nod.

Reyes sat back.

“Alright,” she said. “We’ve said what needed saying. This is the hard part where words end and habits start. You’re all dismissed. Except you, Mills. Stay a minute.”

Chairs scraped.

As they filed out, Doyle paused near Nguyen.

“PFC,” he said.

She looked up at him.

“Yes, Specialist?” she said.

He flinched at the title. Soon, he wouldn’t have it.

“I know you said you’re not my teacher,” he said. “And I won’t make you be. But… thank you. For being honest. You didn’t have to. It would have been easier to say nothing.”

“It wouldn’t have been easier for me,” she said. “Just quieter.”

He nodded, not sure how to respond.

“I’ll see you at PT,” she added. “Don’t be late. It annoys me when people slow me down.”

There was the smallest glint of dry humor in her eyes.

He managed a weak laugh.

“Yes, ma’am— I mean, yes, PFC,” he said.

Cruz tugged his sleeve.

“Come on, man,” he murmured. “We’ve got forms to sign and pride to rebuild.”

They left the room.

Inside, with just Reyes and Mills, the atmosphere relaxed a fraction.

“Come on, Sergeant,” Reyes said. “Tell me honestly. Did I overstep?”

Mills shook his head.

“No, ma’am,” he said. “If anything, you probably saved the kid from spiraling into some self-justifying story about how it ‘wasn’t that bad.’”

He hesitated.

“And you gave Nguyen something she doesn’t get much of,” he added. “A say.”

Reyes nodded.

“I can’t fix every bad moment,” she said. “But I can make sure they don’t disappear into paperwork.”

Mills smiled faintly.

“Ma’am,” he said, “for what it’s worth… seeing you storm into my office scared the hell out of the whole floor. In a good way.”

“Good,” she said. “Fear of paperwork doesn’t change culture. Fear of disappointing something bigger than you sometimes does.”

They both knew it wouldn’t be enough on its own.

But it was a start.

The next morning at 0600, the gym looked the same as always: rubber mats, racks of weights, the smell of disinfectant and effort.

But the pairs on the floor were… different.

PFC Nguyen sat on a rowing machine, hands wrapped around the handle, feet strapped in. She’d already done a careful warm-up, checking her brace.

Next to her, Specialist Doyle—not yet demoted on paperwork, but feeling it in his bones—adjusted the settings on his own rower.

“You sure about this pace?” he asked, eyeing the numbers.

She raised an eyebrow.

“You saying I can’t out-row your perfectly functioning legs?” she asked.

He shook his head, a tiny smile tugging at his mouth despite everything.

“No, PFC,” he said. “I’m saying I’m about to get smoked.”

They started.

Pull. Breathe. Slide.

Nguyen’s movements were smooth, upper body strong, core tight. Doyle realized, fifteen seconds in, that he’d underestimated her. Fully.

By the one-minute mark, his shoulders burned.

By the three-minute mark, sweat dripped into his eyes.

“Total time, ten minutes,” she said between breaths. “Then we rest, then we do planks.”

He groaned.

“Cruel,” he said.

“You have no idea,” she said. “You haven’t met my physical therapist.”

Around them, other soldiers watched with varying degrees of curiosity.

“Is that Doyle?” one whispered. “Working out with the new PFC?”

“Yeah,” another said. “Heard he got his rank knocked for being a jerk to her.”

“Damn,” the first said. “He actually looks like he’s trying, though.”

“Maybe he learned something,” a third said. “Weird, huh?”

Word traveled. It always did.

By the end of the week, the story had shifted: not “the guy who kicked the disabled recruit,” but “the guy who owns up to screwing up and is putting in the work to be better.”

Both were true.

Nguyen still had days where she braced herself before stepping into a crowded hallway. Doyle still had nights where he replayed that moment, wishing he’d shut his mouth and checked his temper.

They were not friends. Not exactly.

But they were teammates.

At the end of the month, after a particularly brutal PT session, they sat on the edge of the mat, drinking water.

“You know what my grandmother used to say when my mom and uncle argued?” Nguyen said suddenly.

“What?” Doyle asked, wiping his face with a towel.

“She’d wait until they moved past the petty stuff,” Nguyen said. “Then she’d lean back, sigh, and say in Vietnamese, ‘Và cuộc tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng.’ It means, ‘And the argument became serious.’”

He nodded slowly.

“This feels… serious,” he said.

“Yeah,” she said. “But serious doesn’t always mean bad. It just means no more pretending it’s about something small.”

He looked around the gym—the adaptive workouts, the subtle new signs reminding everyone of access protocols, the way people moved a little more mindfully around those with braces, canes, or scars.

“Guess we’re all in the serious part now,” he said.

“Good,” she replied. “Maybe that’s where the real work happens.”

He thought about that long after they left the gym.

Months later, when a new intake of recruits arrived, one of them—a kid barely out of high school with a hearing aid tucked behind one ear—hesitated outside the barracks, backpack clutched in hand.

He looked up as a tall sergeant with a limp walked by, nodding kindly.

Behind her, a specialist joked with a private using a cane, both of them adjusting their pace so they walked together.

The new kid’s shoulders relaxed a little.

Maybe, he thought, there was space here for all kinds of strength.

Inside the headquarters, General Reyes signed off on a new policy document: Inclusion and Respect for Soldiers with Disabilities – Fort Anders Implementation Plan.

She looked out the window at the drill field, where formations shifted with practiced precision.

She knew there would be more bad days. More mistakes. More thoughtless words in crowded hallways.

But she also knew there were people now who wouldn’t let those moments slide into silence.

Sometimes all it took was one serious argument, one stormed office, one painful, honest conversation to change the story people told about what it meant to serve.

Not from “toughness means stepping on the weak.”

But from “toughness means lifting together, even when it hurts.”

THE END

News

When an Arrogant General Shoved a Quiet Female Soldier in the Mess Hall, Her Hidden Combat Skills, Ironclad Evidence, and Refusal to Back Down Blew Up the Entire Base’s Power Games in Front of Everyone

When an Arrogant General Shoved a Quiet Female Soldier in the Mess Hall, Her Hidden Combat Skills, Ironclad Evidence, and…

Some recruits thought it was just a joke to shave a female soldier’s head in the barracks, but when her commanding general father walked in, the fallout exposed loyalty, abuse, and what real leadership actually looks like

Some recruits thought it was just a joke to shave a female soldier’s head in the barracks, but when her…

Our Hard-Charging Commander Cornered the Quietest Woman in the Platoon and Ordered Her to Drink from a Filthy Toilet — Thirty Seconds Later He Was Begging Her Not to Repeat His Exact Words to Anyone in the Chain of Command

Our Hard-Charging Commander Cornered the Quietest Woman in the Platoon and Ordered Her to Drink from a Filthy Toilet —…

When the Base General Caught a Female Sergeant Elbow-Deep in Dishwater Instead of at Morning Drill, Their Tense Confrontation Uncovered a Hidden Burden, a Failing System, and a Different Kind of Courage He’d Been Blind To

When the Base General Caught a Female Sergeant Elbow-Deep in Dishwater Instead of at Morning Drill, Their Tense Confrontation Uncovered…

A Ruthless Dealer Snatched the Motorcycle Club President’s Only Daughter Off the Street, and the Way the Club Hunted Him Down, Turned on Each Other, and Finally Delivered Justice Changed Their Brotherhood Forever

A Ruthless Dealer Snatched the Motorcycle Club President’s Only Daughter Off the Street, and the Way the Club Hunted Him…

Thugs Laid Hands on the Biker Club VP’s Quiet Wife One Night, and the Fierce, Unexpected Way the Entire Club Responded Exposed Their True Code—and Nearly Tore Our Family Apart

Thugs Laid Hands on the Biker Club VP’s Quiet Wife One Night, and the Fierce, Unexpected Way the Entire Club…

End of content

No more pages to load