They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell That Could Punch Through a U-Boat’s Pressure Hull and Send It Down With One Hit in the North Atlantic Night

If you stood on the windswept dock at Halifax in 1942, and listened to the officers at the officers’ club after a hard crossing, you’d hear the same grim jokes again and again.

“Three more ships gone.”

“Another convoy hit off Greenland.”

“Two corvettes fired everything they had—came back with empty racks and nothing but oil slicks to show for it.”

And, inevitably:

“Depth charges—great for scaring fish. Not so great for steel tubes that can swim.”

The Battle of the Atlantic was a war of nerves and acoustics.

German U-boats prowled like wolves. Merchant ships, loaded with food and fuel and machines, crept across gray water while escorts strained their ears and eyes. Each night was a gamble. Each dawn was a kind of miracle.

In Ottawa and London, admirals argued over escort routes and convoy sizes.

In Halifax, a handful of engineers and sailors argued over something much narrower and more stubborn:

The size and shape of a shell.

The Problem with Hitting Shadows

Lieutenant Commander Daniel “Dan” McLeod of the Royal Canadian Navy Reserve had seen his share of wakes and wreckage by the time someone handed him a pencil and a problem instead of a pair of binoculars and a ship.

He’d grown up in Lunenburg, son of a fisherman. He knew the sea could be cruel without any help from Germans. But the Germans had arrived anyway—long, low gray shadows with torpedo tubes and a taste for tonnage.

Dan had watched a torpedo hit a freighter once, through his binoculars on a crisp night east of Newfoundland.

A flash.

A plume.

Then the nose of the ship lifting, the stern sliding under.

His corvette had charged in, hurling depth charges overboard in carefully calculated patterns. The sea had boiled. Men had cheered. Then the water had gone still.

No debris.

No oil.

No U-boat.

“Too deep,” the asdic operator had muttered.

“Too late,” the captain had said.

Dan had chewed on that for months.

The problem was simple to describe and maddening to solve: depth charges worked best when you already had a nervous, well-trained enemy exactly where you wanted him.

They had to be set to just the right depth. They had to detonate close enough to deform a pressure hull.

Too shallow, and they kicked up impressive geysers without much else.

Too deep, and they lit up empty darkness.

The U-boats were learning.

They’d shoot, then dive hard and fast. Some would even slide underneath a convoy, betting that escorts wouldn’t dare drop charges beneath their own charges full of TNT and wheat.

“They’re not stupid,” one British liaison officer told him grimly at the Halifax naval base. “Clever chaps. Hard to kill.”

“So give us something better to kill them with,” Dan had snapped back before he could stop himself.

The liaison officer had raised an eyebrow.

“Why don’t you?” he’d replied.

The Shell on the Blackboard

The Naval Armament Depot in Dartmouth, across the harbor from Halifax, was not a glamorous posting.

It smelled of oil and paint and hot metal. On most days, its most exciting event was a test of a new fuse or the arrival of a ship to reload.

In June 1942, it gained one lanky, tired lieutenant commander with salt already burned into his skin.

“McLeod,” the depot’s deputy director, Commander Arthur Howe, said, peering over his glasses. “You’ve annoyed just enough people with your questions to be interesting. The British have this ‘hedgehog’ in development—forward-thrown projectiles that explode on contact. The Americans are working on improved depth charges. We,” he paused, “are going to design something a little different.”

He walked Dan to a blackboard.

On it were three sketches:

A U-boat profile.

A surface escort firing arcs of depth charges.

And, between them, a crude drawing of what looked like an oversized artillery round with fins.

“Guns we already have,” Howe said, tapping the sketch. “Four-inch, three-inch, even some of the old twelve-pounders. Depth charges we already have. But guns fire at periscopes and conning towers. Depth charges go after guesses. What if we put something in between?”

Dan frowned.

“A shell that goes underwater and explodes like a depth charge?” he asked.

“Not turns into a depth charge,” Howe corrected. “Works as a shell underwater. Think of it as a bullet that doesn’t forget how to kill just because it hits water.”

He handed Dan the chalk.

“Design it,” he said.

The tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng almost immediately.

The depot’s senior ballistics officer, a compact man named Keltner, scoffed.

“Artillery shells are designed for air,” he said. “You fire them into water and you waste good cordite. The column collapses, you get a few metres of travel, and then it tumbles.”

The engineer sitting opposite him, a civilian named Margaret “Meg” Sinclair—who’d joined the depot after designing turbine blades for a Montreal firm—shook her head.

“Not necessarily,” she said. “Shape it right, and you can get a stable underwater flight. We’re not talking about kilometers. We’re talking about tens of metres. That’s enough if you aim correctly.”

“The U-Boat is not going to sit politely within tens of metres of where we’d like it,” Keltner replied dryly.

Howe let them go back and forth for a bit.

Then he looked at Dan.

“You’ve seen the real thing, McLeod,” he said. “What would make the most difference on a black night with one chance?”

Dan thought.

He thought of periscopes, of small flashes of steel in moonlight, of scopes vanishing an instant after you saw them.

“I want something,” he said slowly, “that I can fire at that last known position. Something the asdic can refine quickly enough to give me a line, even if not a depth. If the shell goes in within a few yards, and then travels down and forward… it doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to be close enough to hurt.”

He picked up the chalk.

“This,” he said, drawing quickly, “narrow nose, harder than a normal shell, to punch through a few metres of water with less deflection. Stabilizing fins for underwater travel. A fuse that doesn’t care when it leaves the barrel, but notices when pressure changes around it.”

Meg leaned forward.

“Pressure fuse,” she said. “Depth-sensitive.”

“Or better,” Keltner said slowly, “contact fuse that arms after it has passed through the air-water interface and slowed a bit. Otherwise it might go off right at the surface.”

“We could combine,” Meg suggested. “Impact on hull or set for a rough depth band. If it doesn’t hit anything solid by, say, thirty metres, it detonates anyway. A sort of short-range depth charge, but thrown at high speed.”

Howe smiled.

“There,” he said. “Now it’s a Canadian compromise. That means it might actually work.”

They argued late into the night.

About nose angles: “Too sharp and it’ll cavitate. Too blunt and it’ll slow too quickly.”

About explosive fillings: “We need something that doesn’t leak under high pressure and doesn’t disintegrate on impact with water.”

About fuses: “We want it simple enough to mass-produce, robust enough to work under punishing conditions, and clever enough to not blow our own gun mounts apart if it goes rogue.”

Dan watched numbers and diagrams bloom on the blackboard like frost.

He realized something then:

Hell was not only heat and fire and fear.

It was also thousands of small, stubborn problems between intention and effect.

And here, in a drafty building in Nova Scotia, hell looked like chalk dust.

A Shell With Two Lives

By December 1942, they had a prototype.

It was ugly.

It was beautiful.

Forty kilos of steel and explosive, roughly the length of a man’s arm, with a hardened pointed nose and a ring of short, stout fins at its base.

It did not look like an ordinary naval shell.

It looked like something between a spear and a torpedo.

“SN Mk I,” the paperwork called it.

“Submarine Neutralizer, Mark One.”

Sailors called it something else almost immediately.

“Snowball,” one petty officer suggested. “Because it’s Canadian and we’ll be throwing it down their throats.”

The name stuck—although officially it became “SNOWBELL” to give the censors less to chew on.

The first test was done under conditions as controlled as the Atlantic would never be.

A 4-inch gun on a training range fired a Snowbell shell into a calm basin at a measured angle.

Observers with stopwatches and hydrophones recorded everything: entry splash, underwater travel, final detonation.

On the first shot, the shell shattered on impact with the water, scattering fragments in a shallow cone.

“Too fast,” Keltner grumbled. “The nose isn’t strong enough.”

On the second, it held together… and failed to detonate.

“Fuse didn’t arm,” Meg said, brows knit. “Pressure profile was wrong. It thinks it’s still in air.”

On the third, it punched in cleanly, traveled fourteen metres underwater in a wavering line, and detonated in a muffled thump.

“A bit shallow,” Dan noted.

“Still shallow enough to smash periscopes and damage hull plating on a boat at periscope depth,” Howe said.

They refined.

They added a simple pressure bellows to the fuse that wouldn’t fully arm until the shell had passed a few metres underwater, then added a backup clockwork so that even if it swam through empty water, it would still go off within a pre-set time.

They coated the fins in a special anti-corrosion lacquer so they wouldn’t seize after months at sea.

They argued over whether to add tracer.

“If the enemy sees it, they’ll know what we’ve got,” Keltner warned.

“If we don’t see it, we can’t correct fire,” Dan countered.

In the end, they compromised with a faint, dull tracer that wouldn’t be obvious at a distance but gave the firing ship some feedback on entry point.

By spring 1943, they had something that worked well enough in tests to justify the next step:

Letting it loose in the Atlantic.

A Secret Weapon for Small Ships

They could have kept Snowbell for bigger destroyers, with their heavier guns and faster speeds.

They didn’t.

They gave it to the corvettes and frigates that plowed the gray lanes between Halifax, St. John’s, and Liverpool—a decision that owed as much to politics as to tactics.

“Canada’s ships, Canada’s shell,” the Admiralty liaison in Ottawa said. “Let your boys have the first crack at it.”

In reality, it made tactical sense.

The little flower-class corvettes, built in Canadian shipyards and crewed by young men who’d never been farther from home than Boston before the war, were the ones most likely to get in close with U-boats.

They were small, quick, and often underestimated.

Now, some of them carried something new in their magazines: a crate or two marked only with a stenciled snowflake and a classification stamp.

The crews were told only the basics.

“New anti-submarine shell,” the gunnery officer aboard HMCS Saint Croix told his team on a cold April morning. “We fire it from the four-inch gun. If we see a periscope or a snorkel, or if asdic gives us a good line and bad depth, we send a few of these.”

He held one up.

“Do not drop it,” he said.

The men laughed nervously.

In the convoy commodore’s cabin, the briefing was more detailed.

A technician from Halifax ran down the doctrine to a cluster of captains and senior officers.

“This is not a replacement for your depth charges,” he stressed. “Think of it as a scalpel, not a hammer. If you can pin an enemy boat near the surface—forcing it up, or catching it at periscope depth—this will give you a better first blow.”

“How do we know where to aim?” asked one skeptical destroyer captain. “The ocean is deep, and these things don’t chase like torpedoes.”

Dan, now wearing the thin mustache and hollow-eyed look of men who travel too much between desks and decks, stepped in.

“Asdic gives you bearing and range,” he said, “even if it can’t always give exact depth in a hurry. If you see a periscope, you know depth roughly. Fire at the last known position with a spread of shells, just as you would with depth charges, but at an angle that puts them ahead of the boat’s probable path underwater.”

He picked up a stub of chalk and drew on the wardroom’s blackboard: a ship, a line, a U-boat diving.

“Snowbell travels downward and forward,” he said. “If he’s diving, you aim a little short and let him swim into it. If he’s holding depth, you aim right on.”

Heads nodded, dubious but interested.

“And if we miss?” someone called from the back.

Dan smiled thinly.

“Then you fall back on what you’ve always done,” he said. “But at least now, you’ll have something to try before you blow half your depth-charge load on a hunch.”

First Blood in the Fog

The North Atlantic does not respect timetables.

Convoy HG-158 left Liverpool in May 1943 with thirty-five merchantmen and eight escorts, including HMCS Saint Croix and HMCS Drumheller—both carrying a few crates of Snowbell shells.

The sea was cruel first, then quieter, then cruel again.

Fog rolled in off Greenland, thick and damp, shrinking the world to a few ship-lengths and turning asdic into the only real sense that mattered.

On the third night out from Ireland, Saint Croix’s asdic operator—the youngest son of a Halifax dockworker, twenty years old and very awake—heard something beyond the usual noise.

“Contact!” he called. “Range 1800 yards, bearing green ten. Moving slow.”

The captain—a slight man named Fraser who’d once trawled for cod and now trawled for something deadlier—stepped to the asdic console.

“Steady?” he asked.

“Steady, sir,” the operator said. “Looks like he’s swinging in toward the convoy’s track.”

“Probably waiting his moment,” Fraser muttered. “Any sign of a periscope?”

The lookout on the bridge shook his head at first.

Then he stiffened.

“Something there, sir,” he whispered. “At two points off the bow. Just a line. Gone now.”

“Snowbell,” Fraser said.

A chill went through the gunnery crew.

They’d practiced.

They hadn’t fired one in anger yet.

“Range?” Fraser asked again.

“1600… 1500… he’s closing,” the asdic man replied.

“Helm, bring us to green ten,” Fraser ordered. “Gunnery—load Snowbell. First one at that last bearing. Second one five degrees right. Third five degrees left. Fire as soon as you’ve got the solution.”

The gun crew scrambled.

The first Snowbell shell slid into the waiting four-inch barrel with a heavy, deliberate thunk. The breech closed.

Fraser watched the bearing marker shift.

“Now,” he said.

The gun barked.

From the deck, the shell’s entry looked almost unimpressive: a sharp splash, a brief white plume.

Below, it traveled.

Down.

Forward.

The only men who could have seen it were busy listening to their own instruments.

On U-boat U-*** (her number lost later under contested claims and incomplete records), the sound came like a fist on the hull.

The captain—a veteran of North Atlantic patrols who had once described depth charges as “the ocean coughing”—had just given the order to level off at periscope depth after a quiet approach.

He’d raised the scope once, swept it in a smooth circle, and seen the convoy, dark shapes against darker water.

He’d lowered it again, counting seconds.

“Another thirty seconds, then we rise and fire,” he told his first officer.

He never got those thirty seconds.

The Snowbell shell hit just above the pressure hull’s rounding curve, a metre or two behind the conning tower.

Its nose punched through plating that had been inch-thick insurance up until that moment.

The fuse, now armed by pressure, recognized metal and density and gave up its second life.

The detonation was brutal but local.

There was no great cinematic fireball, no external plume.

Inside the U-boat, it was as if the world decided to step sideways.

Light bulbs shattered. Pipes tore loose. Men were thrown against bulkheads. A momentary loss of pressure in one compartment was followed by an obscene rush of water.

On Saint Croix, they heard it on the hydrophones.

“Muffled explosion!” the asdic operator shouted. “Bearing steady! Sir, I think we hit something.”

“Second shell,” Fraser ordered.

There was no need.

U-*** did not have time to level off, to blow ballast, to much of anything.

She filled.

She sank.

On the surface, Saint Croix’s crew saw nothing but a brief boil of water and, minutes later, a slick and a handful of bobbing debris.

A plank.

A hat.

No survivors.

Fraser wrote in his log that night:

“0405 – Fired three SNOWBELL shells at suspected U-Boat. First observed to detonate in close proximity. Subsequent oil patch and wreckage. Assessed destruction of enemy submarine highly probable.”

In Halifax, when the report reached the depot, Meg Sinclair read it twice and allowed herself a rare unguarded grin.

“It works,” she told Howe.

Howe tapped the dispatch soberly.

“Might have been lucky,” he said. “Or it might be the start of something.”

Dan, standing by the window, looking out at the gray harbor, didn’t smile at all.

He remembered the quiet thump through the hull of his corvette when a depth charge had gone off near a U-boat once, and the bitter silence that followed.

He imagined what the men on the other side had felt when the Snowbell hit.

“Once,” he said. “Now we see if it works twice.”

The Debate in London

News of Snowbell’s success reached London courtesy of a British liaison officer who spent more time in transit than at any one desk.

He laid the report on a conference table in the Admiralty and watched the admirals’ faces.

“Canadian shell, Canadian convoy, Canadian kill,” he said. “It seems to have some merit.”

Admiral Sir Percy Noble frowned thoughtfully.

“‘Some merit’ is an understatement if it did what they claim,” he said. “A direct hit on a U-boat hull is no small feat, and to achieve it with an ordinary destroyer’s gun… that’s worth something.”

The Director of Anti-Submarine Warfare, a man whose whole life for the past three years had been numbers and maps and the words “huff-duff” and “asdic,” remained cautious.

“We must be careful not to overstate,” he said. “One patrol, one claimed kill. We have had those before.”

The tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng as more officers chimed in.

“We should get our own stocks,” one said. “Why should the Colonials keep this to themselves?”

“We’re already pushing Hedgehog,” another replied. “Too much variety complicates supply.”

“Hedgehog throws a pattern of bombs ahead that explode on contact with a hull—yes,” someone conceded. “Snowbell, if this report is accurate, offers something else: the ability to engage a boat that has just dived with a gun already in place, without waiting to steam into position for a mortar launch.”

“Train one gun differently,” Noble mused. “Is that so hard?”

“Train gun crews differently, rework magazines, introduce a new fuse, coordinate asdic with gunnery… it all costs time,” the anti-submarine director replied.

“Everything costs time,” Noble said. “The question is, does it save ships?”

He turned to the liaison.

“What does Ottawa want?” he asked.

The liaison smiled faintly.

“For once, sir,” he said, “they’re not asking for more. They’re asking if they should build more of it and whether they can get permission to mount it on more ships.”

“Then we let them,” Noble decided. “For now. Quietly. If it proves itself, we’ll talk about broader deployment. Until then, let the Canadians have their secret snowballs.”

He tapped the report.

“And for heaven’s sake,” he added, “don’t let the papers get ahold of it. The last thing we need is Goebbels telling his sailors we’re lobbing magic bullets at them.”

The U-Boats Notice

The U-boat arm, for all its propaganda, was not blind.

Commanders talked.

They met briefly between patrols in Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire, over thin beer and cigarettes, comparing notes on escorts and tactics.

By mid-1943, they were already complaining about improved radar and high-frequency direction finding.

Now, something else crept into those conversations.

“Depth charges, yes, but this was different,” one captain said, rubbing a scar on his wrist he’d earned when he’d been thrown across the control room. “A sharp impact, like being struck by a hammer from nowhere. No time to register. And the escort wasn’t even on top of us yet.”

“Air attack?” another asked.

“No,” he said. “No aircraft overhead. Sounded like a single shell, then a pressure wave.”

The senior officer listening looked skeptical.

“The English have their Hedgehog,” he said. “Perhaps you encountered that.”

The captain shook his head.

“This came from the side,” he said. “Ahead. From a ship’s gun, I’m certain.”

“Canadians,” someone muttered.

The room laughed.

But the story circulated.

It reached Admiral Dönitz’s staff as a curious note in an intelligence summary:

“Reports from some boats suggest Allied escorts may be employing a new type of shell that can travel underwater and explode near our hulls. Details unclear.”

“England and America both tinker,” Dönitz grunted when he read it. “Let them. Steel and discipline will win.”

He wrote a brief advisory:

“Commanders are reminded to remain cautious when using periscopes near escorts. Do not linger at periscope depth after firing. Dive quickly to safe depths. If possible, increase range to escorts before attack to reduce risk from new weapons.”

For a weapon that officially did not exist, Snowbell was causing adjustments.

That, in its way, was another form of success.

The Night the Debate Went Quiet

In August 1943, Convoy ON-202 met a wolfpack in the mid-Atlantic.

Fog and rain played their usual dirty games.

Torpedoes struck two ships in quick succession.

The escorts—a mix of British destroyers and Canadian corvettes—lunged toward the bearing.

On HMCS Waskesiu, a Snowbell shell waited in her forward gun.

The asdic operator tracked a contact that had fired and turned.

“He’s not diving hard,” the operator reported. “Maintaining depth… might be coming around for another approach.”

“Range?” the captain asked.

“1200 yards… 1100… he’s on our starboard bow now.”

The captain had read Fraser’s report from Saint Croix. He had drilled with Snowbell until his gunners could load and fire in their sleep.

“Bring us to starboard,” he ordered. “Gunnery—one Snowbell at that bearing. Aim slightly ahead of his track. Fire when ready.”

From the U-boat below, the escort’s pivot registered as a distant, growing thrum.

Onboard U-***, the captain considered his own options.

He’d fired one torpedo and heard an impact.

He’d started to shift position to attack from another angle, counting on the escorts’ attention being fixed on the two burning freighters.

Then his hydrophone operator stiffened.

“Escort turning… toward us,” the man said.

“Impossible,” the captain muttered. “They have no contact this quickly.”

On Waskesiu, the gun fired.

The shell splashed in just ahead of where the asdic trace suggested the U-boat would be if it held course and depth.

Underwater, the Snowbell traveled like a slow, determined spear.

The U-boat captain gave the order to dive.

“Down thirty metres,” he snapped. “Quickly.”

They started to slide.

It was not enough.

The shell hit near the forward battery compartment.

It didn’t have to puncture deeply.

A fracture.

A spray.

Battery acid in places it shouldn’t be.

Steam, hissing, then darkness as lights went out.

On the surface, Waskesiu’s asdic man heard the thump and the chorus of smaller sounds that followed.

“Explosions!” he cried. “Multiple. Like internal damage.”

“Mark position,” the captain said. “Depth charges on this spot—just to be sure.”

They dropped a short pattern.

The sea boiled.

When it smoothed again, an oil slick spread, slow and sinister.

A wooden crate popped up, bobbing, split.

A piece of hull plating followed, twisted.

No survivors.

No cheering.

Just tired, grim nods.

In Halifax, when the signal reached Meg, Keltner, Howe, and Dan, they stared at it in silence for a long moment.

Then Howe said, “That makes three.”

Keltner added, “At this rate, someone will want to tell the newspapers.”

“Someone,” Dan said quietly, “will not be us.”

He didn’t say it out of modesty.

He said it because he knew how fragile the advantage was.

Already, the Germans were diving sooner, surfacing less, changing patterns.

Snowbell was not a war-winner alone.

It was a small, sharp edge on an already enormous knife.

Still, on a night in the Atlantic, for a U-boat commander who stayed at periscope depth a moment too long, that edge could be everything.

The Shell That Was Never Named

Snowbell never made the front page.

It never got the glossy magazine spreads that radar and Enigma and aircraft carriers did.

After the war, when histories of the Battle of the Atlantic were written, authors mentioned Hedgehog and Squid and Leigh Lights, but few any secret Canadian shell.

Much of its paperwork stayed in classified files for years; some of it got lost in the shuffle of peace, misfiled under routine ordnance improvements.

The men who designed it went on to other work.

Meg Sinclair returned to turbine design, then eventually to teaching.

Keltner retired to a cottage and yelled at fishermen for using the wrong knots.

Howe took a posting in Ottawa and learned to love paperwork, if not entirely.

Dan ended the war back on a bridge, this time with more gray in his hair and a different kind of tired behind his eyes.

He took HMCS Charlottetown on her last patrol in 1945 with ordinary shells and ordinary depth charges. Snowbell had been a rare, precious thing, never produced in numbers to match the vastness of the sea.

But in quiet reunions in Halifax and St. John’s and Liverpool, among men who had leaned over asdic consoles and gripped gun breech handles in the spray and dark, the story lived.

“Remember that time on Saint Croix?” someone would say.

“The first one? Or the one off Iceland?” another would ask.

“The first,” the storyteller would say. “The night we fired that weird Canadian shell—they told us to load it like a normal round and not to drop it or swear at it or look at it funny—and the asdic man swore he heard that U-boat go from smug to surprised in one second.”

They’d laugh.

Not at the death.

At the memory of feeling, for once, that the killing might go the other way.

“The rest of the world will talk about sonar and codebreaking and aircraft,” one would add, more serious. “All true. All needed. But I’ll tell you—I still remember that Snowbell. It was the first time I felt like we had something they didn’t know about.”

That feeling mattered.

In wars of attrition and nerves, any secret that makes your enemy look over his shoulder is worth the steel.

The Little Edge in a Long War

Did Snowbell—the secret Canadian shell—“send U-boats down with one hit” as the more breathless wartime rumor-mongers liked to claim?

Sometimes.

Not always.

The ocean is large, and luck is unruly.

Some Snowbells went wide.

Some detonated near enough to rattle teeth but not to crumple hulls.

Some sat in magazines until the war ended, their fuses never feeling the cold pressure of deep water.

But in a battle decided by increments—one more convoy through, one more boat lost, one more commander deciding his odds had turned—those increments added up.

Snowbell forced U-boat captains to change behavior.

It gave escort captains a new option in that terrible moment between detection and disappearance.

It proved something else, too:

That innovation in war is not the sole property of huge laboratories or famous names.

Sometimes it is born of a chalkboard in a chilly depot and a fisherman’s son who asks, “Why not?”

The German Kriegsmarine never formally acknowledged Snowbell as a distinct threat.

But in the fading months of the Battle of the Atlantic, as their own debates over tactics and technology grew nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng, one phrase appeared more frequently in their internal memoranda:

“Enemy surface escorts have increased effectiveness at short range. Commanders are advised to minimize time at periscope depth within gun range of escorts.”

That was Snowbell’s invisible signature.

A little more fear in those last seconds before the scope dipped.

A little less confidence that the only danger came from above and behind.

A little more doubt.

In the end, the U-boats were beaten by a coalition of solutions: escort carriers, long-range aircraft, radar, HF/DF, Ultra, improved training.

And somewhere in that crowded, unsung coalition, a Canadian shell with a snowflake stenciled on its crate carried its quiet weight.

Years later, Dan McLeod walked the waterfront in Halifax with his grandson, a boy who had grown up hearing about “the war” the way other children heard about storms.

They stopped near a small memorial, one of many, listing ships and men lost in the Battle of the Atlantic.

“Did you ever sink a submarine, Granddad?” the boy asked, looking up with frank curiosity.

Dan thought of the night on Saint Croix. The first Snowbell. The muted thump. The oil. The bits of wood.

“We tried,” he said. “Most nights we tried. Some nights, we got lucky. Some nights, they did.”

The boy dug in his pocket and produced a small object.

A rusted, finned fragment he’d picked up at a surplus yard near the base.

“Is this from one of your shells?” he asked.

Dan took it, turned it in his fingers.

It could have been.

Or it could have just been a piece of ordinary ordnance, its story lost.

“We built some special ones,” he said. “From here. From Canada. They went into the water and didn’t stop being dangerous just because they left the air.”

The boy’s eyes widened.

“Like a bullet that could swim?” he said.

Dan chuckled.

“Something like that,” he replied.

“Did the Germans know?” the boy asked.

“Not at first,” Dan said. “By the time they started to suspect, it didn’t save them.”

The boy considered that.

“Did it save us?” he asked.

Dan looked out at the harbor.

At the ships.

At the gulls wheeling above.

At the quiet water that once had been anything but.

“Nothing saved us alone,” he said. “We saved each other. One shell, one escort, one convoy at a time.”

He handed the fragment back.

“Keep that,” he said. “Remember that somewhere, someone sat in a cold room and argued about numbers so that someone else could live long enough to argue about something else entirely.”

The boy nodded solemnly.

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll remember.”

They walked on.

The secret Canadian shell that could send a U-boat down with one hit was, by then, a footnote.

But for the men who had fired it in the dark, and for the men who had heard it on the hydrophones on those anxious nights, it remained something more:

Proof that even in the worst kind of sea-bound hell, a little stubborn ingenuity could tilt the odds, one hidden weapon at a time.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

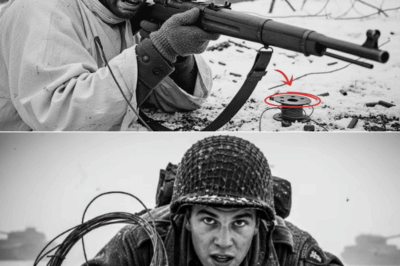

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load