The German Officer Who Looked Out Over the Gray Atlantic, Saw More Than 7,000 Allied Ships on D-Day, and Realized in a Single Shattering Moment That His Country’s Defeat Was No Longer a Question

Captain Ernst Weber had been awake since before dawn on June 6, 1944, but he would spend the rest of his life insisting he truly woke up only once that day.

It was the moment he stepped out onto the wind-blasted observation post on the cliffs above the French coast, lifted his field glasses, and saw an ocean that no longer looked like water.

It looked like steel.

Ships.

As far as his eyes could travel.

And then farther still.

He didn’t know the exact number in that first stunned glance, but he knew it was beyond anything he had imagined. Destroyers, cruisers, transports, small craft darting between them like insects, lumbering cargo vessels, strange ugly shapes he would later learn were called landing ships.

The horizon itself seemed crowded.

For a few seconds, his mind tried to behave like a proper officer’s. It tried to catalog, to count, to measure.

Then something more human, more honest, overruled it.

This is the end, he thought.

Not the beginning of a battle.

Not a difficult day ahead.

Not a tactical challenge.

Just: This is the end.

And for the first time since he had put on a uniform, Ernst Weber understood that his side could not win.

1. Before the Storm

As a boy in southern Germany, Ernst had loved maps more than anything.

While other kids kicked balls in dusty streets, he would sit by the window turning the pages of an atlas until his fingers were faintly ink-stained. Rivers, mountain ranges, coastlines—he could trace them from memory. By twelve, he could point to almost any spot in Europe and tell you the country, the nearest major river, and the old trade routes that had once run nearby.

“You’ll grow up to be a professor,” his mother had teased, ruffling his hair.

He had smiled shyly and kept reading.

But the world had other plans.

History did not ask what Ernst Weber wanted. It rarely asked anyone.

By the time he was old enough to choose a career, the speeches had already filled the air. Promises of restored pride, endless banners, parades, and slogans. A new order. A new future. A new chance for a country still nursing wounds from the last war.

He didn’t like the shouting. He didn’t like the way some neighbors disappeared quietly, or the way others suddenly spoke in lowered voices.

But he loved his country.

He loved his maps.

And he loved the idea, taught in every classroom and repeated in every newspaper, that he was part of something too big to ignore.

“You’re good with geography,” the recruiter had said. “Good with numbers. With observation. You’d make an excellent officer in the coastal defense forces. You’d be defending Europe’s western wall.”

“Defending from whom?” Ernst had asked, naïve.

“From those who want to bring us down again,” the man replied. “From those who cannot stand the idea of a strong Germany.”

It sounded simple then.

Nothing is simple on a cliff above a gray sea filled with ships.

2. Life on the Cliff

By 1944, Captain Ernst Weber had spent almost three years assigned to a sector of the Atlantic Wall along the Normandy coast.

His days had a rhythm.

Wake before dawn.

Check reports from the night watch.

Call in weather readings.

Walk the perimeter, nodding to the young soldiers at their posts.

Drink bitter coffee from a dented metal cup.

Study the sea.

Always, the sea.

The bunkers dug into the earth around him smelled of oil, sweat, and damp stone. The gun emplacements, with their thick concrete and heavy barrels, had been described to him as “impregnable.” Reinforced steel, overlapping fields of fire, interlocking zones of defense.

On paper, it was impressive.

But Ernst had been staring at maps long before he stared at guns.

He knew numbers.

He knew distances.

He knew that calculations on paper rarely survived contact with reality.

He had seen the reports from the Eastern Front. He had heard, in letters from old academy friends, about winter and mud and endless columns of enemy armor. He knew that the war, once described as quick and decisive, had become something else: a grinding, devouring machine that asked for more and more and returned less and less.

He also knew something else, something he never said out loud:

If the enemy ever came across the Channel with everything they had, this wall would hold for a while, perhaps, but not forever.

We are not ready for everything, he thought more than once, staring into the mist. We are ready for raids. For probes. For testing attacks.

Not for a decision.

Still, he followed orders. He trained his men. He inspected guns, supervised drills, studied aerial photographs of the English coast, watched for patrol boats and submarine wakes. On quiet days, he would lean against a cool concrete wall and trace the coastline in his mind, imagining invasion routes like lines on an invisible map.

Sometimes, late at night, he would lower his voice and speak with the older sergeant, Krüger, who had served in the previous war.

“Do you think they’ll come?” Ernst would ask.

Krüger would shrug.

“In the last war we waited for a giant punch that never came,” he would say. “This time, I don’t know. The world seems more impatient.”

“And if they do?”

The older man would exhale slowly.

“Then we’ll do what soldiers always do,” he’d answer. “We’ll hold as long as we can. And after that, history will do whatever it wants with us.”

3. Whispers of an Invasion

By early June, the whispers had turned into something more solid.

Radio intercepts.

Strange movements in the sky.

Increased activity across the Channel.

Orders reaching his sector had become more frequent and more nervous.

“Remain on heightened alert.”

“Expect enemy actions along the coast.”

“Be prepared for diversionary attacks.”

One memo in particular stayed in his mind:

“We must assume the enemy will attempt deception. Do not be fooled by feints. The main thrust will come where it is least expected.”

Which, Ernst thought dryly, could mean almost anywhere.

On the night of June 5, heavy clouds rolled in from the ocean. The wind shifted, a damp chill crawling up from the water. Rain fell in irregular bursts.

In the bunker, the air was uneasy.

Young soldiers played cards with more noise than usual. A radio in a corner murmured dance music, quickly turned down each time an officer entered. Men smoked faster, the cigarettes burning down in nervous bursts.

Ernst stood over a map table, fingers resting lightly on the paper. He watched a single droplet of water, shaken loose from his scarf, fall onto the coastline and spread.

It felt like an omen.

At around midnight, messages began to arrive in rapid succession.

Enemy aircraft sightings.

Reports of parachutes over distant sectors.

Disturbances inland.

“They’re coming,” someone whispered.

Ernst kept his voice calm as he issued orders.

“Double the watch on the seaward approach. Check all ammunition stores. No one sleeps until I say so.”

Outside, the sky flickered occasionally with distant flashes—too far to be local storms, too irregular to be natural.

The invasion, he realized, was no longer a theoretical question on a staff college exam.

It had begun.

4. Dawn Over an Iron Sea

By the time the horizon began to turn the faintest shade of gray, Ernst’s eyes felt like sandpaper.

He had not slept. Neither had most of his men.

The air above the cliffs tasted like salt and exhaust. The sea below was a restless, shifting mass of dark waves.

He stepped out of the bunker into the biting wind and walked toward the observation post. His boots crunched on gravel. Behind him, voices murmured into field radios, relaying fragments of messages that made little sense when heard half-out of context.

He climbed the short ladder to the higher platform.

The wind hit him full in the face, cool and insistent.

For a brief moment, it was quiet.

Then the mist began to thin.

At first, it was just shapes. Smudges on the water. Slightly darker patches in the gray world where sea met sky.

Then the light improved just enough.

And the smudges turned into forms.

He lifted his field glasses.

His breath caught.

Ships.

He would remember later how his brain tried, like a loyal but overwhelmed assistant, to force the scene into something manageable.

Destroyers, he thought. Cruisers. Transports. Landing craft. Escorts…

But every time he tried to categorize, the scene grew.

Row after row of vessels, some close enough that he could see individual lifeboats strapped to their sides, others mere silhouettes farther away. Big ships, fat with cargo. Sleeker shapes bristling with weapons. Tiny specks darting here and there, cutting white scars into the waves.

Smoke hung low over the armada, trailing from funnels in long, horizontal smears.

Radar masts. Signal flags. Antennas.

He swung his glasses left and right.

To the left: more ships.

To the right: more ships.

Beyond them, in the distance: still more.

The numbers rose in his mind, wild and instinctive.

Hundreds.

No. More.

Thousands.

His heart pounded.

An artillery officer nearby, barely older than a boy, clambered up beside him, panting.

“Captain, what do you—”

The young man stopped mid-sentence.

He didn’t need to finish. The question had been answered by the horizon itself.

“Good God,” he whispered.

Ernst lowered the field glasses slowly.

He stared with his naked eyes, as if the glasses were somehow exaggerating the view.

They weren’t.

From his position on the cliff, he could see a portion of the Allied fleet assigned to the sector. He didn’t know the exact number then, but later historians would put it around 7,000 ships of all kinds in the broader invasion.

He didn’t need a precise count.

The human brain has limits, but it knows when something crosses the line from “military force” to “tidal wave”.

“What do we do, sir?” the young officer asked, voice tight.

For a moment, Ernst didn’t answer.

Because the honest answer, the first one that rose up in him, was simply:

We lose.

5. The Moment the War Changed

People would later ask him: When did you know the war was lost?

They expected a strategic answer.

Maybe he should have said “after the defeat in North Africa” or “when the Eastern Front turned into a retreat” or “once the factories began to strain under the bombing.”

Those were all true in their own way.

But in his heart, the answer was simpler:

The war ended for me the moment I saw thousands of ships on that gray morning and understood that no amount of slogans could change what I was looking at.

It wasn’t just the number.

It was what the number meant.

It meant industrial strength on a scale that no one on his side had matched. It meant logistics, planning, fuel, steel, training, coordination. It meant a coalition of countries that had managed to put aside their differences long enough to build a floating city and send it across the sea.

It meant that the enemy was not merely knocking at the door.

It was taking off the hinges.

A cold calm settled over him.

Not panic.

Not even anger.

Just a heavy, irrevocable clarity.

“We man our positions,” he said to the young officer quietly. “We follow our orders. We do our duty. And we do not pretend this is something it is not.”

“What is it, sir?” the young man asked.

“A turning point,” Ernst replied.

He didn’t say the end of our cause. He didn’t say the collapse of everything we were told to believe.

But he thought it.

Deeply.

Irreversibly.

6. Fire from the Sea and Sky

The bombardment began shortly afterward.

It started with a distant rolling thunder, like a storm grumbling beyond the horizon. But the sky was clear of storms. The sound grew, multiplied, layered over itself until it felt less like sound and more like pressure inside the chest.

Then the shells arrived.

Huge naval guns, miles out to sea, spoke in tones that shook the earth under his boots. Explosions bloomed along the coastline, tearing chunks out of concrete and earth. Bunkers that had taken months to build and reinforce shuddered under hits they were never designed to absorb indefinitely.

The air changed flavor, turning metallic and bitter.

Men shouted into radios, into one another’s ears, sometimes into the void when lines were cut.

“Report your status!”

“Hold that position!”

“We’ve lost contact with the battery to the west!”

Through it all, Ernst tried to do what he had been trained to do.

He directed fire where he could, passing coordinates to gun crews that still had working lines of sight. He ordered medics where they were most needed. He shouted encouragement, though it felt thin against the roar from sea and sky.

From his perch, between bouts of shelling, he could still see parts of the armada.

Small landing craft began to peel away from the larger ships and head toward the beaches, packed with men who must have been as frightened as his own.

The sea between fleet and shore became a mess of wakes and white spray.

Above them, Allied planes droned and swooped, some heading inland, others circling like hawks waiting for an opening.

It was chaos on a scale that made any single human feel insignificant.

In that chaos, though, Ernst clung to one thought:

History is watching this day. It will not remember our slogans. It will remember the fact that they could do this and we could not stop it.

7. A Brief Piece of Humanity

At one point, during a lull in the bombardment, a runner stumbled into Ernst’s command post with plaster dust in his hair and a wild look in his eyes.

“Captain! One of the younger soldiers—Becker—he’s asking for permission to pull back from the front trench. He says it’s hopeless, sir. Says there’s no point.”

Ernst rubbed his eyes.

In some ways, Becker was right. The trench line closest to the water line was exposed and likely to be overrun. Still, orders were orders.

“Where is he?” Ernst asked.

“In the communication dugout near section C, sir.”

Ernst made a decision that, years later, he would remember more clearly than almost any order he gave.

“I’ll talk to him myself,” he said.

As he moved down a narrow passage carved through earth and reinforced with timbers, the ground shook again from another distant impact. Dust rained from above. The electric bulbs flickered.

He found Becker sitting on a crate, helmet pushed back, hands shaking.

The young soldier’s eyes darted up when Ernst entered, then widened.

“Captain, I—”

Ernst raised a hand.

“Save your explanation,” he said softly. “Listen instead.”

He crouched to get on eye level with the young man.

“You’re scared,” Ernst stated simply.

Becker swallowed hard.

“Yes, sir,” he admitted, voice cracking.

“So am I,” Ernst replied.

The admission seemed to unfreeze something in the boy’s face.

“It’s just… look at them,” Becker said, the words tumbling out. “There are so many. It’s like they’ve emptied every shipyard in the world. How are we supposed to stop that? What difference does it make if I stay in that trench or not? We can’t win this.”

Ernst studied him.

Once, not so long ago, he might have answered with a speech about duty, about honor, about holding every inch of ground.

But he had seen the ships.

He had tasted the truth in the wind.

“You’re right,” he said quietly. “We cannot stop all of that. Not today. Not from here.”

Becker looked stunned.

“But,” Ernst continued, “we are still soldiers. And soldiers do not choose which orders to obey based on whether they think the war as a whole is winnable. They choose based on what is in front of them, on the men next to them, on the small piece of time they are responsible for.”

He placed a hand briefly on Becker’s shoulder.

“Out there, right now,” he said, “someone on those ships is just as terrified as you are. He has been told he is fighting for something noble, just like you were. He, too, is wondering whether he’ll see another sunrise. Our job, whether we like it or not, is to stand in our place and do what we’ve been told to do. History will sort out who was right in the big picture. We only have this little one.”

Becker’s throat bobbed as he swallowed.

“So what do I do, sir?” he asked.

“You go back to that trench,” Ernst answered gently. “You watch your sector. You keep your head down when you must, and you take your shot when you can. You don’t do it because you think this will change the course of the war. You do it because the man next to you needs to know you’re there.”

For a moment, Becker just stared.

Then he nodded, slowly.

“Yes, sir.”

Ernst watched him go, helmet now pulled low, shoulders squared a little more.

As the young man disappeared into the dim corridor leading back toward the front, Ernst leaned against the wall for just a second longer than was strictly necessary.

He had not lied.

He had simply narrowed the mission.

8. An Ending and a Beginning

By the end of that first day, the coastline below them had changed.

Where there had been empty sand and water in the morning, there were now burning vehicles, scattered equipment, and clusters of men pushing inland. Some of their own bunkers had fallen silent. Others still replied stubbornly with intermittent fire.

Radio messages grew more fragmented.

Some were cut off mid-sentence.

Others repeated the same phrases, as if the sender did not know what else to say.

“Enemy advancing…”

“Requesting support…”

“Unable to hold…”

As afternoon turned into evening, the Allied ships remained, a dark forest of silhouettes against the fading sky.

They had come to stay.

In the bunker, the maps on Ernst’s table were now littered with pencil marks and notes that no longer mattered much. The carefully drawn defensive lines had been pierced. Positions marked in neat ink now existed only as memory.

He sank onto a crate for a moment, feeling the weight of exhaustion settle into his bones.

Later, as he tried to put it into words, he would say:

“It was like watching a tide come in. You can shout at the water all you want. You can build walls, you can dig trenches. It might slow, it might curl, it might splash differently against your defenses. But in the end, if there is enough of it, and it keeps coming… it wins.”

That night, under the sporadic flash of ongoing bombardment and the low buzz of aircraft overhead, he walked out once more to the shattered edge of the cliff.

The wind had turned colder.

He looked down at the beaches, now crawling with movement. Beyond them, inland, faint flashes marked small battles they could no longer influence.

Above, the stars tried to pierce the thin veil of smoke.

This is how empires end, he thought. Not always with a single dramatic moment, but with a day when reality finally becomes too large to ignore.

He knew the war would not officially end for months, perhaps years. There would be more orders, more battles, more speeches from leaders insisting that victory was still possible. But for him, something fundamental had shifted.

The story he had been told about invincibility, destiny, and unbreakable will no longer fit against the picture seared into his mind:

Seven thousand ships.

An ocean of steel.

An undeniable fact.

9. Aftermath

Ernst survived the war.

Not because of extraordinary heroics, nor because he fled his post.

He survived in the same way many did: through a combination of luck, timing, and a handful of decisions on chaotic days that placed him inches away from events that might have ended him.

He spent the last year of the conflict watching his country crack under pressure from both East and West.

He watched the maps he had loved as a child change shape.

He watched borders shift like sand.

He watched leaders grow more desperate in their words even as their power shrank in reality.

When it was finally over, he found himself sitting on a wooden bench outside a building repurposed by the occupying forces, holding a piece of paper that said, in dry bureaucratic language, that he was no longer a prisoner of war.

He stepped out into a world that felt both familiar and alien.

Germany was no longer the place he had marched away from as a young officer, full of complicated pride and unspoken doubt.

It was quieter.

Scuffed.

Humbled.

He moved to a smaller town, far from his old coastal post. He taught geography at a local school. Sometimes the students would ask him about the war, their questions clumsy and earnest.

“Were you brave?”

“Did you see big battles?”

“Whose fault was it?”

He would answer what he could.

He did not describe the fear in detail.

He did not talk about the smell of cordite or the way the earth seemed to breathe under bombardment.

But when they asked about the turning point, about the day he knew it was all over, he always returned to the same story.

“D-Day,” he would say. “June 6, 1944.”

They had heard the name in history class, of course. They recited dates and locations. They knew which side had landed where.

But he had something they did not: a memory behind the textbook.

“I was on a cliff in France,” he would tell them, “looking out over the sea. Our commanders had told us to expect an attack. They had told us we were ready. They had told us that no one could break through our defenses. And then, one morning, I looked through my field glasses and saw so many ships that the water itself seemed to disappear.”

He would pause then, letting them imagine it.

“In that moment,” he continued softly, “I realized that no amount of confidence, no amount of speeches, could change what I was seeing. We were simply outmatched. Not just in numbers, but in preparation, in resources, in the willingness of many nations to work together.”

He would tap the map hanging in the classroom, the lines of coasts and borders.

“History is not decided only by who is right or wrong,” he told them. “It is also decided by who can make what they believe real in the world—who can build, move, supply, and sustain. On that day, I saw that the other side had done this on a scale we had not imagined. And I understood that our story, as we had been told it, would not be the one the world remembered as ‘victory.’”

One student once asked, nervously:

“Do you regret having fought on the losing side?”

Ernst watched the boy’s face carefully.

“I regret,” he said slowly, “that I did not question sooner. That I let pride and fear keep me from seeing what was happening around me before the ships arrived. But I do not regret surviving long enough to tell you about it. If my memory can make you more careful about what stories you believe, then it is worth carrying.”

10. The German Officer and the Map

Years later, when his hair was white and his knees complained about every cold winter morning, Ernst received a letter from an old comrade.

Inside was a single question, written in shaky handwriting:

“Do you ever dream of that day?”

He smiled sadly.

Every time I close my eyes, he thought.

Not in the way of nightmares, exactly. There were enough of those during the first years after the war, but they had faded with time.

It was more like a recurring image.

He would be standing on the cliff again, field glasses in hand, watching the gray morning turn into a sea of metal. But instead of the roar and chaos that had followed in reality, his dream version often ended with silence.

Just him, the wind, and the sight of thousands of ships moving toward shore—silent but unstoppable.

He dipped his pen and replied:

“Yes. I dream of it. Not because of the fighting, but because of the clarity. It was the first time in my life when all the lies, the illusions, and the wishful thinking were stripped away by something no one could argue with: a simple, undeniable fact. There are times when it is painful to remember. But I would rather live with that memory than go back to not knowing.”

In his home, on the wall opposite his favorite chair, hung a large map of Europe.

He had bought it long after the war, when borders had settled into their new lines.

Sometimes he would sit there in the fading light of evening, tracing with a finger the path from his southern hometown to the northern coast where he had once stood in uniform.

He no longer traced battle plans. He no longer thought in terms of fronts and sectors.

Now, when he looked at the map, he thought of people.

Families in small houses.

Fishermen in harbors.

Farmers in fields.

Children in classrooms.

All affected by decisions made far away, by leaders who rarely had to stand on cold cliffs and face the consequences directly.

That, he realized, was another thing D-Day had taught him.

It wasn’t only about the defeat of one army by another.

It was about being reminded that, behind every arrow on a staff map, there were thousands of lives—and that those lives deserved better than to be used as proof of someone’s slogans.

11. The Last Visit

In the autumn of his life, long after the war and long after he had retired from teaching, Ernst made one final journey to the coast where everything had changed.

The world was different now.

Former enemies visited one another’s countries as tourists. Bridges had been built over old wounds—imperfect, perhaps, but real. Memorials dotted the landscape on both sides of the Channel.

He stood once more on a high point near where his old observation post had been.

The concrete bunkers were still there, partially crumbling, their edges worn by time and weather. Some had been turned into small museums. Others had been left as quiet sentinels, half-buried in grass.

Below, the beach seemed peaceful. Families walked along the shore. Children ran ahead, laughing, chased by dogs. A few people stood reading plaques that tried, in neat paragraphs, to explain what had happened here.

The sea was calm.

No armada.

No thunder of guns.

No smoke.

Just waves, rolling in steady, indifferent rhythm.

He closed his eyes for a moment and could almost hear the distant echo of that other morning—the roar, the shouted commands, the crack of artillery.

Then he opened them again and focused on the present.

Two young men nearby were reading an information board in accented English. One wore a British football jersey, the other an American sweatshirt. They pointed at photographs, tracing the outlines of ships and tanks.

“I still can’t believe how many there were,” one of them said.

“Yeah,” the other replied. “It’s crazy. Imagine being on the other side of that, looking out…”

They trailed off, perhaps trying to picture it.

Ernst turned his face back toward the horizon.

Imagine being on the other side.

He didn’t have to.

He had been there.

He had felt the cold clarity of realizing that his country, for all its loudness and cruelty and grand plans, could not withstand what it had brought upon itself.

He had known, standing on that cliff, that defeat was certain.

But he had also come to understand, over the decades since, that certainty was not the end of the story.

What mattered was what his generation, and those that followed, did with that knowledge.

Whether they used it to become bitter.

Or to become wiser.

Standing there in the sea breeze, his coat flapping gently around his legs, he whispered something only the wind could hear:

“We lost that day. But maybe, if we learn from it, someone else wins something more important.”

He stayed until the sun began to sink, turning the water gold.

Then he turned away from the sea and walked back toward the path, his steps slow but steady.

He was just one man.

One pair of eyes that had once looked upon seven thousand ships and understood what they meant.

But as long as he could tell the story, as long as someone was willing to listen, that moment would not be lost.

It would not be just a number in a history book.

It would be a memory passed down:

Of a German officer on a windy cliff who, in a single shattering moment, saw not only the defeat of his country’s war, but the beginning of his own long, difficult journey toward the truth.

THE END

News

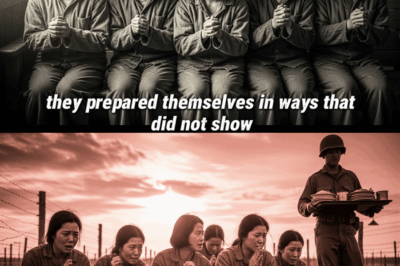

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

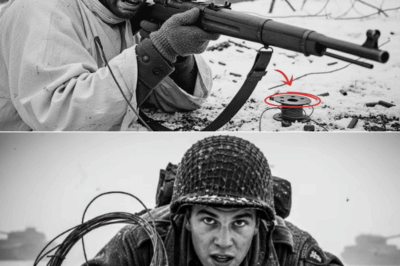

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load