t him several times, off the record, to understand what shame looked like when buried under pride.

Paul told his director Sidney Lumet that he didn’t want to perform Galvin, he wanted to decay into him. That meant looking physically worn. He refused traditional grooming, no hair dye, no flattering angles, no tailored suits. The rumpled overcoat Galvin wore throughout the film was Paul’s personal contribution. He found it in a Boston thrift shop and insisted it remain unwashed throughout the shoot. Every coffee stain and frayed seam became part of Galvin’s slow disintegration.

To convey the character’s alcoholism authentically, Paul did not turn to external mimicry. He pulled from a darker place. During the shoot, he followed what he described as a dry drunk regimen. He gave up alcohol entirely, not to experience sobriety, but to sit in the agitation, the psychological itch. He wanted the tremble in his fingers and the emptiness behind his eyes to feel real. Lumet later shared that Paul would come to set hours early and sit alone in Galvin’s clothes, staring at a wall, muttering pieces of cross-examination under his breath.

The courtroom scenes were filmed in near silence. Paul requested that the set remain hushed so he could hear his own breathing, an effect he believed mirrored the interiority of a man fighting to reclaim a sliver of integrity. The final summation scene, where Galvin pleads not through legal logic but raw humanity, was shot in a single take. Paul did not rehearse it with the cast. He wanted their reactions unfiltered. After the take, the room remained still. No one applauded. Lumet simply said, “That’s it.”

Paul also revealed years later that “The Verdict” (1982) was the first role that made him feel exposed. “Frank Galvin scared me,” he admitted. “He was all the parts of myself I didn’t want to look at. That’s why I had to do it.” During the editing process, he watched a rough cut and left the room mid-way, later confessing to Lumet that it was too painful to witness. Not because the performance felt off, but because it felt too close.

The legal script was dense, and Paul pushed to make sure every courtroom line carried emotional freight. He argued with Mamet over the phrasing of a few key lines, including Galvin’s haunting plea: “If we are to have faith in justice, we need only to believe in ourselves.” Paul believed that line was not just Galvin’s argument, it was a quiet thesis for the entire film. He practiced that delivery alone in his hotel room for a week, using a mirror, then recording and playing it back, each time adjusting pitch and breath until it stopped sounding like a line and started sounding like truth.

He kept the thrift shop overcoat long after filming ended. He said he never wore it again, but couldn’t throw it away either. “It reminds me that sometimes the mess is where the real work begins.”

“The Verdict” (1982) shattered the screen barrier between performance and vulnerability and showed how self-confrontation could be cinema’s deepest form of truth.

News

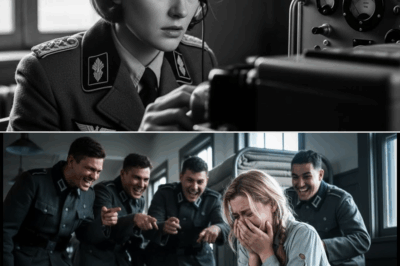

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

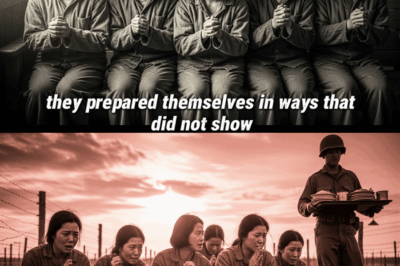

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

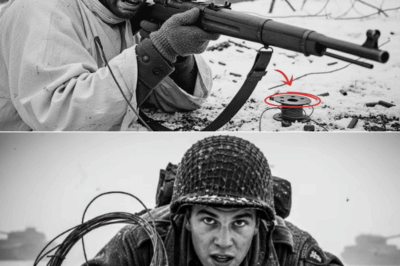

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load