Outgunned, Outnumbered, but Not Out of Courage: How One Little “Tin Can” Destroyer Charged Straight at Japan’s Mighty WWII Fleet and Turned a Hopeless Last Stand Into an Unforgettable Victory at Sea

By the time the crew of the USS Hollins realized they were alone, the coffee in Lieutenant Jack Mercer’s mug had gone cold.

He didn’t notice until the battle alarm ripped through the narrow passageways, turning the ship from a sleepy steel hallway into a hornet’s nest. The mug skidded across the wardroom table as the deck vibrated beneath his boots.

“General quarters! General quarters! All hands man your battle stations! This is not a drill!”

Jack grabbed his helmet, slammed it onto his head, and was halfway out of the wardroom before the mug finally toppled, spilling a dark crescent across a chart of the Philippine Sea.

He never saw it fall.

The USS Hollins was a destroyer escort, which was a fancy way of saying she was one of the smallest warships in the American fleet that still carried guns big enough to make noise.

At 1,400 tons, she was a feather compared to the heavy cruisers and battleships Jack had admired in naval magazines as a kid. The big ships were floating cities; Hollins was a steel town with bad plumbing and thin walls.

They called her a “tin can,” and most days the nickname fit.

She shivered in rough water. Her thin hull didn’t inspire much confidence when the crew saw pictures of enemy eighteen-inch shells. But she was quick and stubborn, with a crew that knew every bolt and pipe like the lines on their own hands.

Jack thundered up the ladder to the open bridge, the cool pre-dawn air slapping him in the face. The sky was a low ceiling of gray, the sea darker still. Far off on the horizon, faint flashes winked like distant lightning.

Captain Daniel Reed stood at the forward edge of the bridge, binoculars pressed to his face. At forty, he was old by the standards of the junior officers, with lines at the corners of his eyes and hair that had begun to gray at the temples. He had the calm, worn look of a man who’d been disappointed by life at least once and survived it.

“XO on the bridge,” Jack said, out of habit.

Reed lowered the binoculars and gave him a quick, tight nod.

“Jack,” he said, skipping formality. “Get your phone talkers wired in and keep the guns talking to me. We’re about to be very busy.”

Jack slid the earphones of his sound-powered phone headset into place, the braided cord trailing back to the fire control board. Voices from below began to chatter in his ear—Gun Mount One, Mount Two, the five-inch director aft, the engine room, damage control.

“Skipper,” Jack said, “what are we looking at?”

Reed handed him the binoculars.

“See for yourself,” he said.

Jack raised the glasses.

He saw, at first, only gray sea and low clouds. Then, as his eyes adjusted, shapes emerged on the edge of vision.

Tall masts. Pagoda towers. Long, low hulls throwing up white fan-shaped bow waves.

Not just one. Not three. A line of them. Many.

“Well,” Jack murmured. “That’s… a lot of ships.”

“That,” Reed said dryly, “is what they told us was not going to happen.”

He glanced at the small formation of escort carriers that Hollins and her sisters had been assigned to protect—the “Taffy” group, slow, thin-skinned ships packed with planes and fuel, never intended to fight a surface battle.

Against submarines? Sure.

Against occasional stray cruisers? Maybe.

Against a major Japanese battle fleet with battleships and heavy cruisers?

That was someone else’s job.

Or it was supposed to be.

“Where are our battleships?” Jack asked, though he already knew the answer.

“South, chasing another force,” Reed replied. “West, covering the straits. Anywhere but here.”

Jack swallowed.

“Intel said anything coming through San Bernardino would be light stuff,” Reed went on. “Scouts, maybe a cruiser or two. Enough for us to annoy and for the carriers to swat from the air. Apparently,” he added, “nobody told the Japanese that.”

Jack focused the binoculars again. The leading enemy ship resolved into a massive shape, larger than anything he’d ever seen in person. Tiered superstructure, huge main guns in triple turrets, secondary guns marching down the hull.

“Battleships,” he said quietly. “Plural.”

“And several heavy cruisers,” Reed said. “Destroyers. The whole orchestra.”

The captain’s tone stayed so calm it almost made Jack angry.

“Range?” Reed asked.

“Radar says about twenty miles and closing,” the officer of the deck replied, checking his scope. “They’re moving fast. Twenty knots plus.”

“They must think they’re charging into a bunch of transports and a scared escort or two,” Reed said. “Which, unfortunately, is exactly what they’ve got.”

For a long second, no one on the bridge spoke.

Out on the dim sea, Japan’s mighty Center Force—ships built for the decisive battle their admirals had dreamed of for decades—was racing straight at a handful of slow escort carriers and seven little “tin cans” like Hollins.

It was exactly the kind of lopsided meeting the textbooks said should never happen.

And yet, here they were.

On the other side of that gray horizon, aboard the massive Japanese battleship Kongo, Commander Isamu Moriya stared at his own set of binoculars and saw a sight that made his mouth tighten.

Little carriers. Slow ones.

And only small escorts around them.

He’d expected to see heavy American units here—big carriers, big cruisers, maybe even one of those new fast battleships that the rumors claimed could keep up with the carriers.

Instead, the ships before him looked like airfields on barges, with small silhouettes flitting around them like anxious sparrows.

“Perhaps they’re decoys,” said his captain quietly beside him.

“Decoys or not,” Moriya replied, “our orders are clear. Break through. Smash the American invasion force at Leyte. Remove their ability to land. The Emperor expects no less.”

He did not say what else he was thinking: that this felt too easy, too exposed, like the first move of a game he didn’t yet understand.

Behind Kongo steamed other giants—Yamato, Nagato, Haruna—and a swarm of heavy cruisers bristling with guns. They had survived air attacks in the narrow seas that morning, been pounded from above but had fought through, trusting their armor and damage control.

Now, ahead lay their chance to use their guns for what they were built for.

“Signal the force,” the captain ordered. “Maximum speed. Prepare for daylight gun action.”

Moriya relayed the order.

Below, in the bowels of the ship, sailors loaded shells the size of small cars into hoists. Powder bags were stacked. Breeches were checked. Men wiped sweat from their faces and tried not to think too much about the planes that would no doubt be back soon.

For the moment, though, the battle would be fought with steel and cordite.

Moriya lifted the binoculars one more time and saw an American destroyer—or something close to it—turning.

Not away.

Toward them.

He frowned.

“What is that little fool doing?” he murmured.

On Hollins, Captain Reed made his decision in less time than it took most men to drink a cup of coffee.

“We can run,” he said. “But we can’t outrun them. They’re faster. Their guns reach farther. If we turn tail now, those carriers die without so much as a scratch on that wall of steel.”

He looked over the bridge at his young executive officer.

“So we’re going to do something they don’t expect,” he said.

Jack’s heart thumped. “Which is?”

Reed turned to the helmsman.

“Come to course zero-eight-zero,” he said. “Flank speed. Directly at the enemy.”

The helmsman blinked.

“Sir?” he said, eyes flicking to the radar scope that still showed blobs much bigger than anything on their side.

“You heard me,” Reed replied. “We’re going in. Hard. We lay down smoke, we make noise, we shoot at anything that looks important, and we launch every torpedo we’ve got. If we’re lucky, we hit something, scare them, make them think there are bigger teeth here than just ours.”

He took a breath.

“If we’re unlucky,” he added quietly, “we die buying time.”

Jack stared at him.

“Sir,” he said, “we’re one little ship.”

Reed’s gaze didn’t waver.

“Then let’s be the loudest one,” he said.

He grabbed the bridge microphone.

“All hands,” he said, his voice steady as steel. “This is the captain. You’ve probably noticed by now that we’ve run into more company than expected. Those are enemy battleships and cruisers ahead—big ones. Our job is to protect the carriers behind us. Nobody else is close enough to do it right now. So Hollins is going to charge. We will make smoke, we will fire our guns, and we will launch our torpedoes. We will draw as much attention as possible away from those flat-tops.”

He paused for a heartbeat that felt like an hour.

“I won’t lie to you,” he continued. “The odds are not good. But if everyone does their job, if we’re stubborn enough and just a little bit lucky, we can give the boys on those carriers time to get their planes in the air and give this whole Japanese fleet something to think about. You’ve trained for this. Trust your ship. Trust each other. Do your duty. That is all.”

He hung the microphone back on its hook.

Silence held the bridge for a second.

Then, from somewhere below, a voice started yelling.

“Hollins! Hollins! Hollins!”

It spread, echoing through passageways and compartments, bouncing off bulkheads and steel ladders.

Jack felt the hair on his arms stand up.

“Well,” Reed said, turning back to the sea. “Let’s go introduce ourselves.”

“Hollins coming to attack course, sir,” Jack reported, his voice calmer than he felt. “We’re headed straight for their lead elements.”

“Signal the carriers,” Reed said. “Tell them we’re making a torpedo run. Tell them to launch everything that can fly and then get the hell out if they have to.”

“Aye, aye.”

Jack relayed the message. Crackling radio replies came back—acknowledgments, hurried blessings, a few clipped words of thanks that sounded almost like farewells.

Across the formation, other tin cans were turning too—Preston, Greer, Lansdale—their captains coming to the same conclusion as Reed.

They couldn’t run. So they would charge.

“Smoke!” Reed ordered. “Get that screen up!”

A white plume began to blossom from Hollins’ stern, a thick, billowing curtain that curled across the water. Other destroyers added their own streaks. Within minutes, a wall of smoke began to bloom between the carriers and the oncoming Japanese line.

It was an old trick—obscure the enemy’s sight, confuse their gunners, hide your vulnerable ships behind a moving fog.

But smoke did nothing against radar.

The Japanese gunnery officers tracked the American formation anyway, their scopes and rangefinders following the bright dots of metal against the sea.

On Kongo, Commander Moriya heard the orders go out.

“Main battery, load armor-piercing! Target the carriers! Secondary guns, target the screening destroyers!”

He watched as the first great guns elevated, rotated, settled.

“Range?” the captain asked.

“Twenty thousand meters and closing.”

“Commence firing.”

The battleship trembled as the first salvo thundered out.

Eighteen-inch shells arced into the sky, brilliant orange flashes marking their births, deep gray smoke smearing the air. Seconds later, the sky over the American formation bloomed with towering waterspouts as the shells slammed into the sea—some short, some long, some straddling startled destroyers with columns of foam.

On Hollins’ bridge, the world shook.

“Shell splashes, port side, close!” the officer of the deck shouted.

Jack felt, rather than heard, the thunder.

Reed’s jaw clenched.

“They’re ranging on us,” he said. “Helm, zigs and zags. Don’t be where they think we are when those monsters land.”

“Yes, sir!” the helmsman called, his hands white-knuckled on the wheel.

The little ship danced, weaving as best it could, leaving a jagged track behind it.

“Gunnery, this is the XO,” Jack said into his headset. “Open fire as soon as you have a target. Aim for the lead cruiser’s superstructure and gun mounts—anything that looks like it makes decisions.”

“Roger that, sir,” came the reply from the five-inch director. “We’ll give them something to chew on.”

Moments later, Hollins’ own guns barked, five-inch shells streaking toward the incoming fleet. They were pinpricks against a wall of armor, but pinpricks could sting—and sometimes, if they hit the right place, they could blind or cripple.

“Hit or at least near miss on that lead cruiser!” the gun captain shouted. “We’re walking the rounds in!”

Jack’s heart hammered as he watched the range numbers spin down on the chart.

“Torpedo range in five minutes, Captain,” he said. “Assuming we’re still here.”

“Let’s make sure we are,” Reed replied.

On Kongo’s bridge, Moriya watched as shell splashes crept closer to the American escorts.

“Increase rate of fire!” an excited gunnery officer yelled. “We have their range now!”

He frowned.

The American destroyers—if they were destroyers—were behaving strangely.

Instead of falling back, staying close to the carriers, they were sprinting forward, charging straight through their own smoke.

A burst of water erupted near the bow of one, drenching it. Another shell landed close enough to lift the little ship partially out of the water. When the spray cleared, she was still moving.

“They are mad,” one junior officer muttered in Japanese.

“Or very brave,” Moriya said.

He thought of the stories he’d heard from older officers about Russian ships at Tsushima, about desperate charges in other wars. This had that smell—a kind of wild courage born of having no good options.

“Do not underestimate a cornered enemy,” he said softly. “Even a small one.”

Aloud, he said, “Keep firing. But tell the destroyer captains to be wary. Those little ships are coming in fast. If they carry torpedoes—”

The rest did not need to be said.

Everyone on that bridge knew what a well-placed torpedo could do, even to a ship as big as Kongo.

Below decks on Hollins, in the cramped torpedo room, Seaman First Class Henry “Hank” Alvarez stared at the gleaming steel cylinders that lay in their racks like sleeping sharks.

“Think they’ll even notice if we hit them?” his buddy, Joe Park, asked, wiping sweat from his forehead.

“If we do it right,” Hank said, “they’ll notice.”

The deck lurched again as another salvo landed close. Dust shook loose from the overhead. Somewhere, something clanged to the deck.

The intercom crackled.

“Torpedo crew, stand by to load and run!” Jack’s voice snapped over the speaker. “We’re making our run now. This is not a practice. I repeat, this is not a practice.”

Hank’s stomach tightened.

“Guess they’re serious,” Joe muttered.

Hank checked the gyro settings on the first torpedo. The numbers on the little dial reflected the carefully calculated angles from topside.

They weren’t aiming at the lead battleship. That was too well-armored and too obvious a target. They were aiming at a heavy cruiser a little closer in—still dangerous, still important, but easier to hurt.

“Ready tube one?” Hank shouted.

“Ready!”

“Tube two?”

“Ready!”

Up above, Captain Reed watched the range slip into the zone where torpedoes, once launched, would have just enough space to arm and hopefully hit.

“Stand by,” he said quietly. “Stand by…”

Shells still came in, towering pillars of water leaping up around Hollins as enemy guns tried to swat her out of existence.

One salvo landed so close to starboard that the destroyer escort felt like she’d been picked up and slapped sideways. Men stumbled. A pipe burst in a shower of spray. Somewhere aft, a small fire broke out, quickly smothered by a damage-control team.

“Rudder responding sluggishly, sir!” the helmsman yelled. “But still responding!”

“She’ll hold,” Reed said, more to himself than anyone else. “She’ll hold long enough.”

He gripped the rail with one hand and the bridge microphone with the other.

“Torpedo crews,” he said. “Fire when ready.”

“Tube one—fire!”

Hank slammed his palm on the lever. The ship shuddered as the first torpedo slid into the sea and dove away in a streak of white bubbles.

“Tube two—fire!”

The second departed, the same strange, hollow feeling in its wake—a sense of having just let go of something that might decide whether you lived or died.

“Reload!” Hank shouted.

There was no time to think about it. Only the mechanical motions drilled into him a hundred times: unlock, slide, latch, check.

Up above, the bridge crew watched the rough bearing of the torpedoes on the plotting board and tried not to flinch at every near miss.

“Time to estimated impact?” Jack asked.

“About two minutes, sir,” the fire control officer said. “If they don’t spot and comb them.”

“If they’re watching us,” Reed said, “maybe they won’t be watching the water.”

On the Japanese cruiser Chokai, Lieutenant Kenji Takada stood in the plotting room, sweating through his shirt.

“Enemy destroyers have launched torpedoes, sir!” a sonar operator called. “Multiple props in the water!”

“Bearing?” the captain snapped.

“Zero-eight-five to zero-nine-zero. Closing fast.”

The captain’s face tightened.

“Hard to starboard!” he ordered. “Signal the other ships: incoming fish!”

The helmsman spun his wheel. Engines throbbed as Chokai tried to turn toward the incoming threat, presenting a narrower target to the torpedoes.

On Kongo, similar warnings flashed through the command net.

The great battleship began her own turn, slower and more stately, like a sumo wrestler pivoting away from a charging opponent.

But torpedoes did not care about pride.

One of Hollins’s steel sharks, thrown into the water at just the right angle and speed, found its way not into Kongo’s side but toward Chokai’s bow, where her armor tapered.

The explosion, when it came, felt to Kenji like the world had been kicked.

The bow lifted, then slammed back down. Men were thrown from their feet. Lights flickered.

“Direct hit, forward section!” someone shouted. “Flooding in compartments one and two! Fires in the forward magazine area!”

The captain barked orders, damage control teams sprinted, pumps engaged—but Chokai was suddenly a wounded animal, her speed dropping, her beautiful bow now a twisted mess.

From the bridge of Hollins, the crew saw only a distant flash and a bloom of smoke near one of the cruisers.

“Yes!” someone shouted. “We hit her! We hit her!”

Jack felt exhilaration rise in his chest like a tide.

Reed didn’t smile, but his eyes glinted.

“Good shooting,” he said. “Let’s try not to get killed celebrating.”

A second explosion erupted near another Japanese ship, this one a smaller destroyer that had wandered into unexpected danger. One of Hollins’s sister ships, charging in from another angle, had scored her own hit.

For a brief, impossible moment, the impossible did not feel entirely impossible.

Seven tiny tin cans had just bloodied the nose of one of the most powerful fleets ever assembled.

They paid for it almost immediately.

The Japanese, stung by the torpedo strikes and annoyed by the persistent stinging of five-inch shells, focused more of their fire on the charging escorts.

Hollins took her first solid hit ten minutes later.

The shell was likely a secondary-gun round from a cruiser—smaller than the main batteries but still plenty big for a thin-skinned ship.

It punched through the starboard side near the forward gun mount and detonated inside a storage compartment.

The blast threw Jack to the deck, ears ringing. The world went bright, then dark, then bright again.

He tasted metal and smoke.

“Report!” Reed shouted over the din. “What’d we take?”

“Hit in forward section!” came the reply from damage control. “Deck two. Fire in compartment fourteen, some flooding. We’re sending teams.”

Jack dragged himself to his feet, ignoring the throbbing in his shoulder.

“You okay?” Reed asked.

“Fine,” Jack lied. “Just got introduced to the floor a little too fast.”

On the bow, the forward gun crew scrambled back to their feet, shaking off concussion. One man clutched his arm, grimacing, but the rest were already swinging their mount back onto target.

“Gun One to bridge!” the mount captain called. “Still here. Still shooting.”

Reed closed his eyes for the briefest second, then opened them again.

“Good,” he said. “Make every round count.”

The battle raged on in bursts.

Planes from the escort carriers, finally airborne, darted overhead, diving on the Japanese ships with bombs and torpedoes of their own. Pilots in Avenger torpedo bombers flew so low their wheels almost kissed the waves, loosing their payloads and then clawing for sky as anti-aircraft fire stitched the air around them.

Some did not make it.

Others did, their torpedoes adding more chaos to the Japanese formation.

On Kongo, Moriya’s respect for the enemy destroyers grew with each minute.

“They are fighting like tigers,” he said quietly to the captain. “Small tigers, but tigers.”

“Annoying tigers,” the captain replied. “We are here to destroy carriers, and instead we are swatting mosquitoes while they sting us.”

“They have already taken one cruiser out of line,” Moriya pointed out. “If the Americans are willing to sacrifice these little ships, they may buy enough time for their carriers to escape.”

The captain grunted.

“Run down the carriers,” he ordered. “Press the attack. They cannot be allowed to live.”

But radar reports told a different story.

The carriers, shielded by smoke and the heroic interference of the tin cans, were turning away, their flight decks still launching and recovering planes.

“Sir,” a junior officer said softly, pointing at the fuel and ammunition reports, “we have taken more damage than expected already. And the planes… they keep coming.”

He didn’t need to say more.

The fleet had survived one air gauntlet that morning. It was now bleeding from a dozen cuts. The thought of running into another ambush farther along the path, perhaps from bigger American ships waiting over the horizon, gnawed at every man on that bridge.

Even the bravest admiral knows when he is sailing into shadows.

Moriya looked again at the little destroyers, still throwing themselves forward, still laying smoke, still launching whatever they had left.

“Sometimes,” he said quietly, “the size of the ship does not decide the size of the story.”

He wondered, not for the first time, what it must feel like to charge a battleship in something that could be holed by a single lucky shell.

On Hollins, the world had shrunk to noise and tasks.

“Flooding in compartment twenty! Pumps two and three engaged!”

“Fire in aft galley! Under control!”

“Gun Two reports barrel hot—we need a brief cool-down or we’ll cook off rounds!”

“Torpedo room exhausted inventory, Captain. We’re down to harsh language.”

“Then use it creatively,” Reed shot back.

Jack bounced from station to station, plugging holes in information where he could, trying to keep the captain’s picture of the battle as clear as possible.

“We’ve bought the carriers some distance,” he reported. “Radar shows them eight, nine miles farther away than when we started. The enemy line is still coming, but slower, more erratic. Those torpedo hits and bomb hits have them tangled.”

Reed nodded.

“Good,” he said. “Now we just have to not die for another thirty minutes.”

As if the enemy had overheard, a salvo from one of the heavy cruisers bracketed Hollins perfectly.

One shell landed just off the port bow, drenching the forward mount and tearing at the plating with fragments. Another fell just aft on starboard, shoving the ship sideways with a blast of water. The third came down directly on the aft section.

The hit was like being punched by a giant.

The deck heaved. A roar filled Jack’s ears. The aft five-inch gun went silent.

“Report!” Reed yelled, gripping the rail hard enough that his knuckles went white.

“Aft section took a major hit!” came the halting reply. “We’ve lost Mount Two. Fire and damage to the depth charge racks… and…”

The voice paused for a beat.

“…and we’ve lost some people, sir.”

Jack closed his eyes briefly.

“How bad?” Reed asked, his voice level.

“Bad,” the reply came.

For a moment, there was no sound on the bridge except the rush of wind and the distant thunder of guns.

Reed swallowed.

“Get the fires out,” he said. “Get the wounded forward. We’re not out of this fight until we can’t move or the captain is asleep, and I feel very awake.”

Jack stared at him.

“Sir,” he said quietly, “we’ve done more than anyone could ask. We’ve hit a cruiser, we’ve drawn fire, we’ve given the carriers a chance. Maybe it’s time to peel off, lay smoke, fall back into the screen—”

Reed cut him off with a look.

“Jack,” he said, “if you’re going to argue for survival, pick a better moment.”

He turned back to the helmsman.

“Course zero-nine-zero,” he said. “Keep us between those guns and those carriers as long as you can keep the wheel moving.”

Jack felt heat rise in his chest.

He wasn’t afraid to die. Not exactly. He’d made peace with the idea that any day might be the last. But dying had always been a vague cloud out on the horizon, not a specific line of paint on a chart.

He took a deep breath.

“Aye, aye, sir,” he said. “I’ll tell the men we’re staying in the dance.”

“Tell them,” Reed replied softly, “that as long as those planes can keep making runs, as long as those flat-tops can keep sending them, we make it worth it. That’s our job.”

Hours later—though it felt like days—the impossible battle finally began to slide toward its end.

The Japanese, frustrated by the torpedo attacks, battered by air strikes that kept pouring in from the withdrawing carriers and other groups farther east, slowed and then turned away.

It wasn’t a grand, dramatic about-face. It was more like a huge animal, bleeding from many cuts, deciding that the meal ahead wasn’t worth more wounds.

On Kongo, Moriya heard the flag signal and saw the turn begin.

“Order from the flagship,” a signal officer said, voice tight. “Break off. Regroup to the north.”

Moriya looked at the receding American smoke and thought of the small ships still darting in and out of it, like angry bees.

“Those little destroyers did their work well,” he said to no one in particular.

He wondered if the men on them would ever know that their charge had helped change an admiral’s mind.

On Hollins, the announcement came as a simple report from radar.

“Enemy ships altering course!” the operator said. “They’re… sir, they’re turning away.”

Jack stared at the scope.

“Confirm that,” Reed said.

“I’m seeing it too,” another officer added, looking through his own instruments. “Their wakes are changing. They’re no longer closing. They’re… zigzagging. Pulling back.”

The word felt foreign, almost unreal.

“Pulling back,” Reed repeated softly.

For several long seconds, no one cheered. They were too tired, too bruised, too aware of the damage around them.

Then someone on the bridge started clapping.

It was a small sound at first, thin as the patter of rain on metal. Then it grew. Voices rose from the deck below, from the gun mounts, from the engine room, carried through open hatches and up ladders.

“Hollins! Hollins! Hollins!”

Reed held up a hand, and the noise died down enough for him to speak into the internal microphone.

“All hands,” he said, “this is the captain. You did it. I don’t know what the historians will say about this day, I don’t know what the admirals will write in their reports, but I know what I saw. A handful of small ships and some tired pilots took on a fleet that should have crushed us and made it turn around.”

His voice tightened just a fraction.

“We’ve taken hits. We’ve lost good men. But those carriers behind us are still afloat, and because they are, this whole war moves one step closer to ending. You did that. You should be proud.”

He let go of the mic and exhaled.

Jack stared at the receding shapes on the horizon and felt something in his chest loosen.

“We’re still here,” he whispered.

Reed heard him.

“Yeah,” the captain said. “Against all odds, we’re still here.”

Then he added, quietly enough that only Jack heard:

“Let’s make sure we remember the ones who aren’t.”

Thirty years later, in a small town in Iowa, Jack Mercer sat at a kitchen table, flipping through an old photo album with his grandson, Tyler.

The boy was ten, with a mop of hair and the kind of wide, curious eyes that took everything in.

“Who’s that?” Tyler asked, pointing at a black-and-white photo of a skinny young man standing on the deck of a warship, helmet crooked, life jacket half-buckled, grin tired but stubborn.

“That,” Jack said, “is a fellow who hadn’t yet learned how much coffee he could drink in one night.”

Tyler rolled his eyes. “Grandpa,” he said. “That’s you.”

Jack smiled.

“Guilty,” he said.

“What ship is that?” Tyler asked, tracing the faint outline of the hull number on the sailor’s cap.

“That’s the USS Hollins,” Jack said. “She was small, noisy, and smelled like fuel and socks most days. But she had a good heart.”

“Dad says you fought in some big battle,” Tyler said. “With a lot of ships. And you were in this tiny ship and the other side had giant ones.”

Jack chuckled.

“Your dad likes to make things sound more dramatic,” he said. “But… he’s not completely wrong.”

He turned the page.

There, taped carefully, was a yellowed clipping from an old newspaper. The headline was bold:

TIN CANS VS. TITANS:

HOW SMALL SHIPS TURNED BACK A GIANT FLEET

Underneath was a grainy artist’s rendering of tiny destroyers charging toward towering enemy battleships, smoke and spray everywhere.

“It was called the Battle off Samar,” Jack said. “Part of a bigger fight in the Philippines. We were supposed to be way behind the lines, chasing submarines and watching for stray raiders. Instead, we woke up one morning and found the main Japanese battle fleet heading straight for us and the carriers we were guarding.”

He leaned back, the chair creaking.

“We were one tiny ship against a whole lot of might,” he said. “Not just us, of course—there were other destroyers, other escorts, brave pilots—but it sure felt small when you looked at those big guns.”

“What did you do?” Tyler asked, eyes wide.

Jack looked at his grandson and saw in that bright, unlined face a future that men had died for without ever knowing the details.

“We charged,” Jack said simply.

Tyler’s jaw dropped. “You went toward them?”

“Yep.”

“Why?”

Jack thought about the question.

“Because running wouldn’t have helped,” he said. “We couldn’t outrun their shells. And if we’d just tried to hide, those carriers behind us would have been torn apart. The men flying from them, the sailors on their decks… they were counting on us to make a lot of noise and be a big enough nuisance that the enemy had to deal with us.”

“But you were so small,” Tyler said.

Jack smiled faintly.

“Turns out,” he said, “size isn’t everything.”

He tapped the newspaper clipping.

“We laid smoke. We fired our guns until the barrels were hot. We launched our torpedoes. We took hits. We lost friends. But in the end, that big, mighty fleet turned around. Maybe we weren’t the only reason. The planes did their part. Fear of other American fleets did their part. But we were one of the reasons. Little ships with big courage.”

He hesitated.

“And on the other side,” he added, “there were men just like us. Sailors who loaded shells, officers who worried about fuel, kids barely older than you working in hot engine rooms. They did what their country told them to do, we did what ours told us to do, and somewhere in the middle, the sea decided who lived and who didn’t.”

Tyler was quiet for a moment.

“Do you ever feel bad for them?” he asked. “The people on the other ships?”

“All the time,” Jack said softly. “Back then, it was easier to see them as just ‘the enemy.’ Big shapes on the horizon. Targets. But later… I realized every ship we hit had people who laughed, who wrote letters home, who had someone waiting for them.”

He closed the book for a moment, resting his hand on the cover.

“The miracle,” he said, “isn’t that one tiny ship fought a huge fleet. Ships can be replaced. Steel can be bent. The miracle is that enough people on both sides survived to build something better afterward.”

He looked at Tyler.

“I fought so you could sit here and ask me hard questions over chocolate milk,” he said with a crooked smile. “I’d say that’s worth a few scary mornings.”

Tyler grinned.

“Did you get scared?” he asked.

Jack laughed softly.

“Oh, kiddo,” he said. “I was scared out of my mind. Anyone who tells you they weren’t scared in a situation like that either doesn’t remember right or wasn’t paying attention. The trick is not letting the fear drive the car. You let it sit in the backseat and keep your hands on the wheel.”

Tyler thought about that.

“If I’m ever scared,” he said, “I’ll try to remember that.”

“That’s all any of us can do,” Jack replied.

He opened the album again and pointed to a picture of a line of skinny young men on a dock, arms slung over each other’s shoulders.

“These are the ones who didn’t come home,” he said quietly. “At least, not all of them. We tell their stories so they don’t vanish completely.”

Tyler traced their faces with a finger.

“Grandpa?” he asked. “Do you think one little person can still make a difference now? You know… without ships and stuff?”

Jack smiled, his eyes crinkling.

“I think that’s the only way anything ever changes,” he said. “One person decides to do the brave thing, even if there’s a much bigger problem staring at them. One person stands up when everyone else is sitting down. One person says, ‘I’ll go,’ when the odds say, ‘You’re crazy.’”

He tapped his chest.

“In our case, it was one little ship against a huge fleet,” he said. “In your case, it might be one honest voice in a loud room. But the principle is the same.”

Tyler was quiet for a long moment.

Finally, he nodded.

“I’m glad you were on that ship,” he said. “And that it didn’t sink.”

Jack chuckled.

“Me too, kid,” he said. “Me too.”

He looked out the kitchen window for a moment, past the neatly trimmed lawn and the maple tree where two birds argued over a twig.

In his mind, he saw again the gray dawn over the Philippine Sea, the looming shapes of battleships, the thin line of tin cans charging into the impossible.

He heard the roar of guns, the crash of waves, the shouted orders. He smelled the sharp tang of smoke and seawater.

And he felt, as he always did when he remembered that day, an odd mixture of pride and humility.

He had been one officer on one tiny ship.

Yet somehow, in that brief, terrifying slice of time, he had been part of something large enough to bend the path of a mighty fleet.

“The impossible battle,” the books called it now.

Out there on the horizon, the old ghosts would always be battling, frozen in memory.

Back here, at a kitchen table, an old man and a child turned the pages of a fading album and quietly agreed that courage did not come in tons or inches of armor.

It came in heartbeats.

One at a time.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

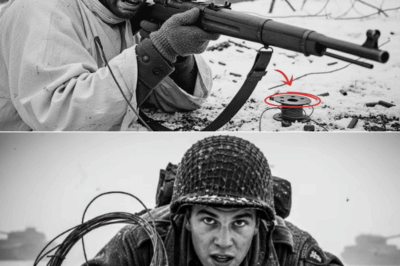

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load