My Brother Died When We Were Kids and My Family Buried the Truth With Him, but When He Called Me at 2 A.M. Saying, “David… It’s Tommy,” the Terrifying Argument That Followed Finally Forced Every Dark Secret Into the Light

When my brother died, they told me time would dull it.

They didn’t say the dullness would feel like a stone I had to carry around for the rest of my life.

Tommy drowned in the river behind our house when he was ten.

I was sixteen, old enough that everyone decided I could survive the kind of guilt no one should ever give a kid. I was the one who’d taken him down there. I was the one who’d been looking the other way.

That was forty-two years ago.

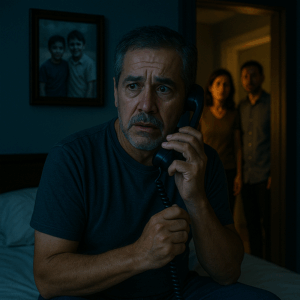

Last week, he called me at 2 A.M.

“David…” The voice came thin and crackly through my bedroom in the dark. “…it’s Tommy.”

I sat up so fast my back spasmed.

My phone glowed on the nightstand, screen a sharp square of light in the black.

Unknown caller, it said.

The room smelled like dust and sleep and the faint citrus of my wife’s lotion.

“Hello?” I croaked.

“It’s me,” the voice said. “Don’t hang up. I don’t have much time.”

My heart thudded in my throat.

“Who is this?” I whispered, though I already knew the answer I didn’t want.

A soft exhale, like a kid steadying himself.

“Dave,” he said. “It’s Tommy.”

The human brain is strange.

In the space of a heartbeat, mine tried to do four things at once:

Reject it. Tommy is dead. Has been dead since 1982. Non-negotiable fact.

Analyze it. Prank? Wrong number? Some scam with an AI voice thing my daughter keeps warning me about?

Remember. The way he said “Dave,” dragging the vowel just a little. That particular squeak on the “v.” The way he always sounded like he was on the edge of laughing.

Feel. A rush of love and grief so strong it was like being slammed with a wave.

I gripped the phone so hard my knuckles hurt.

“Tommy’s dead,” I said. The words came out flat, automatic, like I’d said them too many times. “This isn’t funny.”

The voice on the other end went quiet.

For a second, all I heard was static and faint breathing.

Then, very softly: “I know.”

Something in my chest twisted.

He sounded older than he should have. Like a kid who’d been trying to talk through a wall for four decades.

“I don’t have much time,” he repeated. “They don’t… it’s hard to… I need you to remember.”

“Remember what?” I asked.

“You forgot what really happened,” he said. “By the river. You forgot what they did.”

My mouth went dry.

“No,” I said. “I remember everything.”

I remembered the sun glittering on the water. I remembered the snap of branches under our sneakers. I remembered turning my head for one second because a car door slammed up on the road and I’d been sure Dad had caught us sneaking off chores.

I remembered the splash.

The screaming.

The emptiness in Mom’s eyes at the funeral.

“You don’t,” he said.

His voice crackled, distant and close all at once.

“If you remembered, you wouldn’t have stayed,” he said. “You wouldn’t have let them keep it buried.”

“Who?” I demanded. “Who are you talking about?”

Silence.

“Tommy,” I said, voice shaking. “If this is you—if this is really you—where are you calling from? How are you—”

The line hissed.

“Go back,” he said. “To the river. To the tree. It’s still there.”

“What’s still there?” I asked.

The phone went dead.

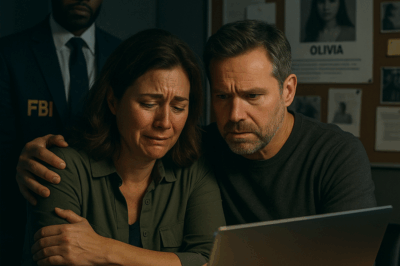

“David?”

The bedside lamp clicked on.

My wife Nora squinted at me, hair mashed on one side, pillow creases on her cheek.

“What are you doing?” she mumbled. “Why are you yelling?”

“I’m not yelling,” I said automatically, though my voice had obviously been raised. My throat felt raw.

Her gaze slid to the clock.

“Who was that?” she asked. “At this hour?”

“I…” I looked at the phone in my hand.

No missed call.

No recent caller.

Nothing.

Just my wallpaper—a photo of our granddaughter Charlotte, cheeks smeared with birthday cake.

“It was an unknown number,” I said. “Wrong number, probably.”

Nora pushed herself up, the sheets falling to her lap.

“David,” she said. “I’ve known you thirty-six years. You look like you just saw a ghost.”

I swallowed.

“Not a ghost,” I said. “A… memory.”

She studied me.

“Did you have another nightmare?” she asked gently. “About Tommy?”

“No,” I said. “Yes. I don’t know. It felt… real.”

Her expression softened in that way I sometimes resent and sometimes am grateful for.

“Hey,” she said softly, reaching for my hand. “Come here.”

I let her pull me back down.

Her arms were warm, solid.

“Breathe,” she murmured. “In for four, out for six. Like Dr. Patel showed you.”

I closed my eyes.

The therapist’s trick worked, sort of. My heart slowed. My muscles unclenched one by one.

But in the quiet, I could still hear it.

The crackle. The voice.

Go back. To the river. To the tree.

“It was him,” I said.

Nora’s hand paused on my back.

“Who?” she asked.

“Tommy,” I whispered. “He… he called me.”

She went still for a fraction of a second.

Then she resumed the soft circles on my spine.

“It just felt like that,” she said. “Sometimes dreams are that vivid. Your mind mixes sounds from outside with old memories. A car backfiring becomes a gunshot in a dream. A ringtone becomes—”

“It wasn’t a dream,” I said, heat rising. “I was awake. The phone rang. I answered it.”

She sighed.

“Let me see,” she said, reaching for the phone.

Reluctantly, I handed it over.

She swiped.

“No calls since Claire this afternoon,” she said. “Remember? About the Halloween thing at Charlotte’s school?”

I frowned.

“That’s not possible,” I said. “I saw it. Unknown caller. Right there.”

“Maybe you dreamed that part,” she said. “Sometimes you wake up and your brain fills in the gaps.”

Her tone was kind.

It still felt like sandpaper.

“I’m not losing it,” I snapped.

“I didn’t say you were,” she said, a touch of defensiveness creeping in. “I’m saying you’ve been under a lot of stress, and we both know this time of year is hard.”

She didn’t have to explain.

October.

The month Tommy died.

Every October, the ghosts got louder.

For me, anyway.

“Maybe it was one of those AI scam calls,” she went on. “Charlotte was telling me about them. They use old recordings to fake someone’s voice. You know, ‘Grandma, I’m in trouble, send money’ sort of thing. Maybe someone found a clip of Tommy from the old home videos, and—”

“No,” I said sharply. “That’s not… no one has those tapes but me. And Mom and Dad never recorded more than three, and the audio was so bad you can barely tell who’s who.”

I heard the edge in my voice and winced.

“I’m sorry,” I added. “I just… it didn’t feel like a scam.”

“It felt like him,” she said softly.

“Yes,” I said. “Exactly.”

She put the phone back on the nightstand.

“Okay,” she said. “Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that you somehow… connected with Tommy. Call it a dream, call it something else. What did he say?”

I hesitated.

“Go back to the river,” I said. “To the tree. He said I forgot what really happened. That I forgot what they did.”

“The river,” she repeated slowly. “The one behind your first house.”

“Yeah,” I said.

She bit her lip.

“Maybe…” She stopped. Started again. “Maybe it’s your brain telling you there’s something you haven’t processed. Something you need to face. You’ve never gone back there, David. Not once.”

“Why would I?” I asked. “To relive the worst day of my life?”

“Maybe to stop letting it live in every other day,” she said gently.

I stared at the ceiling.

“I can’t believe you’re making this into some therapy homework,” I muttered. “My dead kid brother supposedly calls me from beyond, and your takeaway is ‘exposure exercise.’”

Her hand dropped from my back.

“The argument just turned serious,” she said quietly. “Are you really going to be mad at me for trying to help you make sense of something impossible?”

I rolled onto my back.

She sat cross-legged, the sheet draped over her lap, eyes flashing.

“What do you want me to say, David?” she asked. “That yes, your brother dialed you up from wherever he is now and gave you a mission? That there’s some grand mystery and you’re the only one who can solve it? Because if that’s what you need, I can say it. But is that going to help you sleep next week? Next year?”

“It might help me breathe tonight,” I said.

“Or it might yank you back into a guilt spiral you’ve been crawling out of for forty years,” she shot back. “I know you. You’ll obsess. You’ll drive out there alone. You’ll stand on the riverbank and blame yourself all over again.”

“Maybe I deserve to,” I said.

Her face softened.

“No,” she said. “You don’t. You were sixteen. You were a kid, too. You didn’t push him. You didn’t hold him under.”

“Maybe I did,” I whispered. “Maybe I just forgot.”

She flinched.

“Don’t say that,” she said. “That’s not—”

“How do you know?” I demanded. “You weren’t there. Mom and Dad barely talked about it. The police report might as well have been a grocery list. ‘Boy slipped, currents strong, call it a day.’ Everyone decided it was an accident and moved on. I’m the only one who never got to move on.”

Nora’s eyes shimmered.

“That’s not true,” she said. “Your mom—”

“Cut me out,” I said. “Afterward. She looked at me like I was the stranger who came to the door to tell her the bad news. Dad drank more than he spoke. Lisa went to college and pretended she was an only child. We never talked about Tommy again. Except in my head.”

The words came out harsher than I meant.

Nora took a breath.

“I am not your mom,” she said quietly. “I’m not going to cut you off because you’re hurting. But I’m also not going to nod and smile while you slide into something that looks a lot like the breakdown you had after she died.”

That shut me up.

Because she was right.

I’d lost Mom and almost lost myself with her. The panic attacks, the insomnia, the bottomless grief. If Nora hadn’t found me at three in the morning sitting in the garage with the car running, insisting I was “just thinking,” I don’t know where I’d be.

We both remembered Dr. Patel saying, “You’re vulnerable to falling into old patterns when big anniversaries come up. Watch for signs.”

Was this a sign?

Or was this… something else?

“I’m not asking you to believe me,” I said finally. “I’m asking you to trust that this feels different. I’ve had nightmares about Tommy every October since I turned eighteen. Never like this. Never a voice that… that clear.”

She looked at me for a long time.

“Then let’s do this together,” she said. “You don’t go there alone. We go. In daylight. We park on the road like normal people. We walk down to the river. We look. We see if there’s anything that needs… remembering.”

“Tomorrow,” I said automatically.

“Today,” she corrected, glancing at the clock. “In a few hours. After coffee. And after you get at least another two hours of sleep, or you’ll decide every leaf is a message from beyond.”

I almost smiled.

“Okay,” I said. “Deal.”

She lay back down and turned off the light.

In the darkness, I listened to her breathing even out.

My own breath matched hers.

But sleep didn’t come.

When the first gray hint of dawn seeped around the curtains, I was still staring at the ceiling.

Still hearing his voice.

Go back. To the river. To the tree.

The drive back to my childhood town takes an hour and a half if traffic is kind.

That morning, it felt shorter and longer at the same time.

Shorter, because my mind was spinning so fast I barely registered the exits.

Longer, because every mile marker felt like a countdown I couldn’t stop.

Nora drove.

“You okay?” she asked every fifteen minutes.

“I’m fine,” I lied.

She snorted softly each time, like she didn’t believe me but also wasn’t going to push.

The town hadn’t changed as much as I’d expected.

A new gas station. A chain coffee shop where the old diner used to be. A row of condos squatting where Mr. Alvarez’s cornfield used to stretch toward the highway.

But the bones were the same.

The old church steeple.

The brick library.

The worn-out park with the crooked swings.

My stomach flipped as we turned onto my old street.

The house at the end of the cul-de-sac—ours once, someone else’s now—was a different color, a grayish blue instead of the pale yellow Mom had favored. The shutters were new. The big maple tree out front was gone, stump ground down.

But the backyard line of trees still stood, a ragged row of green.

Beyond them, hidden, lay the river.

I could almost hear it from the street, though I knew that was memory, not sound.

“You don’t have to do this,” Nora said quietly, parking a few houses down so we wouldn’t look like creepers staking out the place.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

We walked up the sidewalk.

The cool October air smelled like wet leaves and distant chimney smoke.

No one was outside.

The current owners had put up one of those little plastic fences to keep kids from wandering too far back. The yard was leaf-strewn, a couple of toys abandoned near the swing set.

We slipped between two houses and followed the old path my sneakers remembered better than my conscious mind did.

Branches grabbed at my jacket.

The ground dipped.

And then, suddenly, there it was.

The river.

Forty-two years ago, it had seemed huge.

Now, it looked… smaller.

The water moved steadily, dark and cold, ripples catching the weak sunlight.

On the opposite bank, a cluster of trees leaned toward the water like they’d been eavesdropping on time.

“That’s where you were?” Nora asked, nodding toward a patch of flattened grass near the bend.

“Yes,” I said. “We used to dig for ‘treasure’ there. Bottles, rusty nails. Mom hated it.”

“And the tree?” she asked.

I scanned the bank.

Most of the trees were younger, thinner.

But there, near the bend, was the old one.

A big sycamore, trunk scarred with years of kids’ carvings. Its roots jutted into the water like grasping fingers.

I remembered Tommy climbing that tree, yelling down that he could see all the way to town.

I remembered telling him to be careful.

I remembered turning away when that car door slammed on the road above, heart lurching because Dad had forbidden us from coming down here alone.

The memory snagged.

Except… had it been Dad’s car?

Had he even been home that afternoon?

I frowned.

“What?” Nora asked.

“The car,” I said. “I always thought… I heard a car door slam right before…”

“Before the splash,” she said gently.

“Yeah,” I said. “I assumed it was Dad. I never asked.”

“You were sixteen,” she reminded me. “Maybe your brain just… filled in gaps.”

“Tommy said I forgot what they did,” I said quietly. “Them. Plural.”

“Who’s ‘they’?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “That’s what scares me.”

We stood in silence.

The river gurgled along, uncaring.

Wind rattled the leaves.

I walked closer to the sycamore, my shoes sinking slightly into the damp earth.

As I approached, I saw it.

At eye level, carved into the trunk, faded but still visible:

D + T

Inside a crooked heart.

My throat tightened.

“He made me do that,” I said. “Said I’d forget him someday if I didn’t leave a mark.”

“You didn’t,” Nora said. “Forget him.”

“Maybe I forgot something worse,” I muttered.

I walked around the tree.

On the side facing the river, near where the roots plunged into the bank, the soil looked… disturbed.

Not recently.

Eroded.

But there was a dip there that didn’t match the rest of the worn slope.

A patch of earth more compacted, almost circular.

“What’s that?” Nora asked.

“Could be animal,” I said. “Could be… I don’t know.”

I crouched.

My knees popped, protesting.

I dug my fingers into the dirt.

They hit something hard.

Metallic.

Not a root.

“Nora,” I said. “There’s something…”

I scraped away more soil.

A piece of rusted metal came into view.

Roughly rectangular.

My breath caught.

“Careful,” she said. “You don’t know what—”

I pulled.

The object came free with a wet sucking sound.

It was a box.

Or what was left of one.

A rusty, mud-caked cash box, maybe six inches long, the kind mom-and-pop shops used to keep under the counter.

“You’re kidding,” Nora said.

I stared at it.

Waterlogged, corroded, edges eaten away.

But still a box.

“What is that doing here?” she asked.

“I have no idea,” I said.

My heart hammered.

Tommy’s voice in my head: It’s still there.

“Should we open it?” she asked.

“Out here?” I said, glancing at the river. “What if it falls apart?”

She nodded.

“Back at the car,” she said. “We can put a towel down.”

We walked back the way we came, the box heavier than it looked in my hands.

Every step felt like walking backward through time.

At home, we put the box on the kitchen table.

It left a wet, muddy ring on the wood.

Nora spread out some old newspapers.

“You sure you want to do this now?” she asked. “We could… call someone. A historian. Or the police. Or your sister.”

“Lisa wouldn’t pick up,” I said automatically, reaching for a screwdriver.

She frowned.

“You haven’t talked to her in months?” she asked.

“Years,” I corrected. “We texted at Dad’s funeral. That was it.”

“You really know how to hold a grudge,” she said.

“Not a grudge,” I said. “A… distance. It’s different.”

“Is it?” she asked softly.

I didn’t answer.

Instead, I wedged the screwdriver into the rusted lock and twisted.

It gave with a screech.

The lid stuck, then jerked open.

Inside, there was a stack of plastic-wrapped bundles.

Old, but surprisingly intact.

I picked one up carefully.

“Are those… cash?” Nora whispered.

The top bill was stiff with age, but the face on it was familiar.

Andrew Jackson stared up at me.

“Twenty-dollar bills,” I said. “A lot of them.”

We stared at the box.

There were at least ten bundles.

“Who buries a box of money by a river?” Nora asked. “This isn’t a movie.”

“Criminals who can’t get to a bank,” I said.

Or panicked parents trying to hide something.

The memory snapped into sharper focus.

The car door slam.

The shouting.

Not mine.

Not Tommy’s.

Adults’.

Male.

Two of them.

My stomach dropped.

“Nora,” I said slowly. “I don’t think this is random.”

“You think it’s connected,” she said. “To Tommy.”

“He said, ‘what they did,’” I said. “Not ‘what you did.’ What if… what if he didn’t just slip? What if there was someone else here that day? Some kind of… deal?”

She stared at the money.

“Your dad worked at the bank back then, right?” she said, mind already whirring.

“Yeah,” I said. “Small-town branch manager. Knew everyone’s business. Had keys to everything.”

“And your mom was a teller,” she said.

I nodded.

“You think they robbed their own bank?” she said, half-disbelieving, half-intrigued.

“No,” I said. “I think maybe someone else did. And Dad helped them. Or didn’t report it. Or… something.”

We sat in silence, the decades collapsing around us like an accordion.

I thought of Dad’s sudden “bonus” that year. How we’d gotten new bikes and Mom had a nicer car. How he’d brushed off her questions with, “I got a raise, Anna, don’t worry about it.”

I thought of the way he’d shut down any mention of the bank afterward.

I thought of the way he’d held me so tightly at the hospital, whispering, “Don’t say anything. You didn’t see anything. You were at home. You were with me.”

Had I repressed that?

Or rewritten it?

“I need to talk to Lisa,” I said.

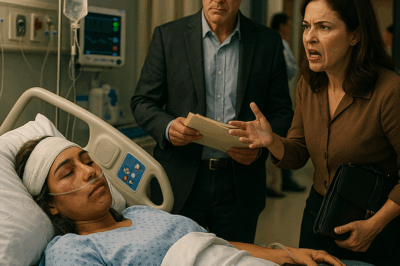

My sister answered on the third ring.

“Hello?” she said, voice wary.

“It’s me,” I said. “David.”

A pause.

“Wow,” she said. “Is it October already?”

I ignored the jab.

“Do you remember the day Tommy died?” I asked.

She snorted.

“Subtle,” she said. “Hi, how are you, Lisa, how’s your life, by the way, do you remember the worst day of our childhood?”

“Do you?” I pressed.

She sighed.

“Of course I do,” she said. “What is this about?”

“I found something,” I said. “By the river. A box. Full of cash.”

Silence.

“Lisa,” I said. “Are you still there?”

“You went back,” she said. “After all this time. You actually went back.”

“He called me,” I blurted.

She made a strange sound.

“Who did?” she asked.

“Tommy,” I said.

Lisa let out a breath that sounded suspiciously like a curse.

“Of course he did,” she muttered. “And of course you listened.”

“What is that supposed to mean?” I demanded.

“It means you never could leave it alone,” she said. “Some of us moved on. You stayed there. In the river.”

“He said I forgot what really happened,” I said. “He said I forgot what they did.”

Another pause.

“Bring the box,” she said finally. “And Nora. Don’t come alone. We need to talk.”

Lisa lived in a brick house in the suburbs, the kind with manicured hedges and a tasteful wreath on the front door.

She answered wearing leggings, an oversized sweater, and the expression of someone who hadn’t slept much.

“Let me see it,” she said without hello.

We put the box on her kitchen table.

Her husband Mark (yes, two Marks; they’d met us once and joked the universe was lazy) hovered in the doorway, concern written all over his face.

Lisa peeled back one of the plastic-wrapped bundles.

“Dad,” she said.

Not a question.

A statement.

“You knew,” I said.

She swallowed.

“I suspected,” she said. “I was twelve. I heard things. I saw things. But I didn’t… I never went down there.”

“You heard him tell me not to talk,” I said, the memory bubbling up: Lisa peeking around the hospital curtain, eyes wide, then disappearing.

“I heard him coaching you,” she corrected. “Telling you what to say to the police. ‘We went down to the river, we played, he slipped, you ran for help, but it was too late.’ Over and over, like a script.”

“You never said anything,” I said.

“And you never asked,” she shot back.

We stared at each other.

Mark cleared his throat.

“I’m going to… give you guys some space,” he said, backing out of the room.

“Who’s ‘they’?” I asked. “Tommy said, ‘what they did.’ Was it Dad and… who? Someone from the bank?”

Lisa scoffed.

“You really want to tear this open now?” she said. “Forty-two years later? He’s dead. Mom’s gone. The bank’s under new management. What does it matter?”

“It matters because my dead brother called me and told me to remember,” I said. “It matters because I’ve been carrying around guilt for something I might not have been responsible for.”

“You were there,” she said. “That’s enough responsibility.”

“I was a kid,” I said. “Dad was the adult. If he… if he did something, or let something happen, or covered something up, that’s on him.”

She looked away.

“That’s convenient,” she muttered.

Anger flared.

“The argument just turned serious,” I said, echoing Nora’s words from the night before. “You want to blame me forever because it’s easier than admitting Dad wasn’t the hero you made him into.”

“I never made him into anything,” she snapped. “He was who he was. Flawed. Stubborn. Scared. He did what he thought he had to do.”

“To protect himself,” I said. “Not us. Not Tommy.”

“You don’t know that,” she said. “You’re filling in gaps with ghost stories.”

“Then tell me what you know,” I said. “No gaps. No ghosts.”

She rubbed her temples.

“I heard him on the phone the night before,” she said slowly. “Talking to someone named Phil. From the bank. They were arguing. Something about numbers not matching. About ‘borrowing’ from a dormant account.”

My stomach twisted.

“Embezzlement,” I said.

“Call it what you want,” she said. “They called it ‘adjusting the ledger.’ Mom walked in, asked what was going on. He told her not to worry, that everything would be fixed by Monday.”

“The accident was Saturday,” I said.

She nodded.

“The next morning, he was gone early,” she continued. “Said he had to go into the office. Mom was mad, said it was supposed to be a family day. He said he’d make it up to us. When he came back, he was… off. Jumpy. Kept looking out the window. Checking his watch.”

The memory slotted into place.

Dad pacing.

Glancing toward the back door.

Saying, “Why don’t you boys go outside, get some air,” in a voice that was too bright.

“When you two went to the river, I was in my room,” Lisa said. “Listening to music. Crying because Mom told me I couldn’t go to the mall with my friends. I heard a car pull up. Voices. Dad and someone else. They were arguing.”

“By the fence,” I whispered. “That’s the car door slam I heard.”

“They didn’t see you leave,” she said. “I watched from my window. Dad pointed toward the trees. The other man—Phil, I think—was waving his arms. I couldn’t hear the words. Just the tone. The panic.”

“Then Tommy fell,” I said.

She closed her eyes.

“I heard Mom scream your name,” she said. “I ran downstairs. You were on the patio, soaking wet, shaking, yelling, ‘He’s not breathing!’ Dad was right behind you, already on the phone with 911, saying, ‘My son slipped, he fell in the river.’ His hands were shaking, but his voice was calm. Too calm.”

“Did you see anyone else?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“Just Dad,” she said. “Later, I heard him telling Mom, ‘We can’t add anything to this. No more trouble. We say it was an accident, we leave it at that. For the boys’ sake.’”

“For the boys’ sake,” I repeated, bitterness creeping in. “Or for his job’s sake.”

Lisa stared at the box.

“I think Phil dropped that,” she said. “Or buried it. Maybe they did it together. Maybe they were going to move it later. Tommy always liked digging around that tree. Maybe he saw something. Maybe he picked it up. Maybe…”

She trailed off.

We didn’t need to finish.

If Tommy had startled Phil, or Dad, or whoever was down there, if there was a struggle, if someone grabbed and slipped and—

I forced my brain to stop.

“That doesn’t excuse Dad lying,” I said. “Or dragging me into the lie.”

“He thought he was protecting you,” she said weakly. “If there was a trial, if people started talking, if reporters came—”

“If,” I said. “You’re doing a lot of defending for someone who knew he stole money and let his son die because he was too scared to tell the truth.”

Her eyes flashed.

“Don’t talk about him like that,” she snapped. “He was still our father.”

“And Tommy was still our brother,” I said. “And I am still the one who wakes up hearing him call my name.”

She flinched.

“So what do you want?” she demanded. “To march into the bank and accuse a bunch of strangers of a crime from the eighties? To dig up Dad’s grave and shout at his coffin? To make some grand statement about justice forty years too late?”

“I want the truth,” I said. “On paper. In my head. Not just in whispers and half-memories.”

“And then what?” she pressed. “What does that fix?”

“Maybe nothing,” I said. “Maybe everything.”

She looked tired.

So tired.

“David,” she said. “We all made choices back then. Bad ones. Scared ones. Mom decided not to ask questions because she couldn’t bear the answers. I decided not to tell you what I heard because I wanted one parent left who didn’t look broken when they saw me. You decided to carry all of it on your shoulders because you thought that was what being the oldest meant.”

She reached across the table, fingers brushing the edge of the box.

“Maybe Tommy’s call wasn’t about solving some crime,” she said. “Maybe it was about getting you to finally drop this weight. To see that even if Dad did something awful, it was his choice. Not yours.”

I stared at her.

“At least now we know,” she added. “Or at least, we know more. Enough to stop wondering.”

“Do we?” I asked.

She nodded.

“For me, yes,” she said. “For you… that’s up to you.”

That night, back at home, I sat alone in the living room.

The box was gone.

We’d decided to turn it over to the police, anonymously.

“Finders keepers doesn’t apply to potentially stolen bank funds,” Nora had said, attempting a joke that landed only halfway.

I could tell she was worried about me.

“Do you want me to sleep on the couch?” she’d asked, hovering on the stairs. “So you’re not alone down here?”

“I’m fine,” I’d said. “Really. Go up. I’ll be there soon.”

Now, in the quiet glow of the table lamp, the house hummed with all the normal sounds—fridge cycling, pipes ticking—but underneath it, the river sounded louder.

You forgot what really happened.

You forgot what they did.

“I remember now,” I said into the empty room. “Okay? Are you happy?”

The digital clock on the cable box flipped from 1:59 to 2:00.

My phone buzzed.

My heart stopped.

Unknown caller, the screen read.

My hand shook as I answered.

“David,” the voice said, clearer this time. “It’s Tommy.”

I let out a breath that was half-laugh, half-sob.

“You have impeccable timing,” I said. “You know that?”

He laughed.

That laugh.

High, quick, with a little hitch on the inhale.

My eyes burned.

“You went back,” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “We found something.”

“I know,” he said. “Thank you.”

“For what?” I asked. “For digging up a crime scene? For yelling at Lisa? For realizing Dad wasn’t the saint I wanted him to be?”

“For not thinking it was all your fault anymore,” he said.

“How do you know what I think?” I asked, wiping at my eyes.

“Been watching,” he said simply.

“From where?” I asked.

Silence.

Then: “It’s not like that. Not clouds and harps. More like… points. Moments. When you say my name. When you look at the picture in the hallway and then look away.”

I swallowed.

“What happened that day?” I asked. “Really.”

He was quiet for a long moment.

Water rushed faintly in the background, or maybe that was in my head.

“I slipped,” he said. “I really did. I was showing off. Trying to get closer to the water to look at something shiny. I didn’t see the edge. I fell.”

I closed my eyes.

“I tried to get to you,” I said hoarsely. “I remember. I jumped in. The current—”

“You did,” he said quickly. “You jumped in. You grabbed my shirt. We both went under. It was cold. It was so cold. And then… arms. Big arms. Pulling me. Pushing you.”

“Dad,” I whispered.

“And someone else,” he said. “They were both yelling. At each other. At us. At the sky. I don’t remember the words. Just… fear.”

He paused.

“I think they were already there,” he added. “Before we came. I think they heard us and panicked. I think if they’d been there a minute earlier, they might have yelled at us to go away. Or… maybe they wouldn’t have. I don’t know.”

I gripped the phone tighter.

“So it was an accident,” I said. “Still. Just… with witnesses you didn’t want.”

“For me, it was an accident,” Tommy said. “For them, it was a choice afterward. To tell the truth or not. That’s on them. Not you.”

Tears slid hot down my face.

“I was supposed to be watching you,” I said. “Mom trusted me. I looked away.”

“For half a second,” he said. “Because you were sixteen and scared of Dad’s temper. You didn’t shove me. You didn’t hold my head under. You’re allowed to be sixteen in this story too, you know.”

I laughed, ugly and wet.

“You sound old,” I said.

“I’m ten,” he said. “And… not. It’s confusing.”

“Tell me one thing that only you would know,” I said suddenly. “Something no one else could fake. So I can stop wondering if I’m having some kind of… break.”

He thought for a second.

“Okay,” he said. “You remember the time you tried to teach me to ride your bike? Not the blue one. The red one. The one with the squeaky brakes.”

“Yes,” I said. “You crashed into Mrs. Van Buren’s rose bushes.”

“And I cried,” he said. “Not because of the scratches. Because you laughed. Not at me. I know that now. You laughed because you were scared and relieved and the whole thing looked ridiculous. But at the time, I thought you were laughing at me. You told Mom later you felt bad, and she said, ‘Sometimes laughter comes out where tears should be.’ You didn’t understand. You do now.”

My breath hitched.

“I never told anyone that,” I said.

“I know,” he said. “You keep a lot of things inside, Dave. Maybe stop doing that so much.”

The ache in my chest eased.

Just a little.

“Why now?” I asked. “Why wait forty-two years to call me?”

“Time doesn’t work like that here,” he said. “It’s all… mushed. But for you, it was time. Dad’s gone. Mom’s gone. Lisa’s almost ready to let some things go. You were… ripe.”

I snorted despite myself.

“Ripe,” I repeated. “Like a banana.”

He laughed.

“I have to go,” he said. “It’s hard to stay.”

“Will I… hear from you again?” I asked.

“Maybe,” he said. “But you don’t need me to tell you what to do anymore.”

“What should I do?” I asked anyway.

He hesitated.

“Live,” he said simply. “Let the river be a river again. Not a grave. Let Dad be… complicated. Not a monster, not a hero. Call Lisa more. Hug Nora. Tell Charlotte how to stay away from fast water and faster boys.”

My throat tightened.

“I miss you,” I said.

“I know,” he said. “It’s okay. I’m… okay.”

The line crackled.

“Tommy?” I said.

“Hey, Dave?” he said.

“Yeah?”

“You were a good brother,” he said. “You are.”

The call dropped.

The phone went dark.

Nora found me on the couch an hour later, the phone still in my hand, my eyes swollen.

“Did he call again?” she asked softly.

I nodded.

“And?” she asked.

“And I think…” I took a deep breath. “I think I can finally stop thinking the whole story is my fault.”

She sat down beside me and pulled me into a hug without saying anything.

Outside, the world went on.

Cars passed.

Dogs barked.

Somewhere, a kid laughed.

The river in my mind finally slowed.

Not gone.

Not erased.

Just… part of the landscape, not the whole map.

Later that week, I drove back to my hometown alone.

I stood on the bank of the river in the thin autumn sun.

I looked at the tree, at the place where the box had been.

I said his name out loud.

“Tommy,” I said. “I remember now.”

The wind picked up, rustling the leaves.

For a second, the sound almost made a word.

I didn’t try to catch it.

I didn’t need to.

I turned and walked back up the path, toward my car, toward home.

Toward a life where my brother was still gone, still loved, and—for the first time in four decades—no longer the weight around my neck.

Just the name carved in a tree, and in my heart.

THE END

News

The Man Who Betrayed My Dad, Caused His Death, Then

The Man Who Betrayed My Dad, Caused His Death, Then Married My Mom Always Called Himself Our “Savior,” but When…

I Thought I’d Left the Iron Kings Years Ago, but When

I Thought I’d Left the Iron Kings Years Ago, but When Their Bikes Surrounded Our Home, They Locked My Eight-Months-Pregnant…

I Thought I’d Left the Iron Kings Years Ago, but When

I Thought I’d Left the Iron Kings Years Ago, but When Their Bikes Surrounded Our Home, They Locked My Eight-Months-Pregnant…

The night my battered twin brother arrived at my

The night my battered twin brother arrived at my house with one eye, talking about his wife’s cartel relatives, secret…

The FBI Closed My Missing Person Case After Months

The FBI Closed My Missing Person Case After Months of Silence, but a Blurry Clip Titled “The Hunt” on a…

I Was in a Coma After a Crash When My Greedy Family

I Was in a Coma After a Crash When My Greedy Family Tried to Sell My House and End My…

End of content

No more pages to load