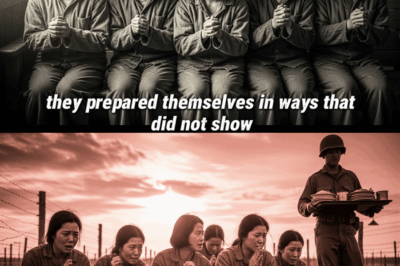

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

The first time Sergeant Jack Mercer heard the phrase, it slipped out so quietly he almost thought he’d imagined it.

“It hurts when I sit,” the woman murmured.

She said it in halting English, each word careful and fragile, like stepping stones across a river. Jack was kneeling in the doorway of a low, cracked barracks in the hills of Luzon, his helmet pushed back, the air heavy with the smell of damp wood, sickness, and fear.

He looked up from the notepad in his hand.

“I’m sorry, ma’am?” he asked.

The woman hugged a thin blanket tighter around her shoulders. Her dark hair, once probably tied with care and precision, hung loose and tangled. She couldn’t have been more than thirty. Behind her, on rows of rough wooden bunks, more women watched with wary eyes.

She swallowed, searching for the words again.

“Sit,” she said, tapping the edge of the bunk. “Here.” She tried to lower herself and flinched sharply, the muscles in her jaw tightening. “Hurts.”

Jack’s stomach twisted. He’d been a cop back in Ohio before the war, so he’d seen things. Bar fights gone bad. A man who’d taken a steel pipe to the ribs. A car crash where the driver had gone through the windshield.

But he’d never seen this many people broken in so many quiet, invisible ways.

He closed the notebook. “You don’t have to show me,” he said. “I believe you.”

Behind him, the medic, Corporal “Doc” Reynolds, was moving cot to cot with his bag, checking fevers, bandaging sores, handing out pills like miracles. Two other GIs stood guard in the doorway, rifles slung across their chests, though everyone in the room knew that if trouble came, it wouldn’t come from the women.

The war was almost over. Everyone said so. But nobody had warned them what the end would look like.

They’d found the camp by accident.

Task Force Luther was pushing deeper into the mountains, chasing rumors of a retreating enemy unit that refused to surrender. The fighting had been sharp and mean — ambushes from ridges, booby traps hidden under leaves, sniper fire snapping out of the dark jungle like angry bees.

On the third day, around mid-morning, their point man, Private Joe Harper, spotted the fence.

It wasn’t much of a fence. Rusted wire, sagging between rough posts. A desperate sort of fence, the kind you throw up when you’re more worried about what’s outside than what’s inside.

“Hey, Sarge,” Harper called quietly, raising his hand. “You’re gonna want to see this.”

They spread out, moving low and careful, ears tuned for any sound of gunfire. But all they heard was wind going through the trees and something that sounded like a soft, ragged cough.

Beyond the fence, there were three long wooden buildings, a small shack that might once have been a guard post, and a yard of bare earth worn smooth by countless footsteps.

“Looks like a camp,” said Lieutenant Harris, squinting through his binoculars. “But it’s way too small to be a regular POW compound.”

Jack raised his own field glasses. At first, he thought the yard was empty.

Then he saw her.

A figure at the far end of the compound, standing near a rain barrel, watching them. She had a faded uniform jacket pulled tight around her, sleeves rolled up to her thin forearms. Her eyes were big and dark and still.

“Lieutenant,” Jack said quietly, “those are not soldiers.”

As if the woman at the barrel were a signal, a few more faces appeared at the windows. Then a few more. Some stayed half-hidden behind boards. Some stepped out into the light, shading their eyes, too tired or desperate to hide.

“Holy…” Doc whispered under his breath. “They’re women.”

The unit froze. They’d all heard rumors. Stories swapped in mess tents and on troop ships. Camps that held civilians. Harsh treatment. People caught between armies and forgotten.

Off in the trees, a bird called once, sharp and lonely.

“What’s a group of Japanese women doing out here?” Private Lewis muttered. “Thought all their civilians stayed back home.”

“Don’t assume you know their whole empire,” Doc said, his voice tight. “Could be nurses. Could be workers. Could be anything.”

Lieutenant Harris lowered the binoculars. His jaw was clenched.

“All right,” he said. “We do this by the book. Mercer, you take first squad. We go in slow, weapons ready, but no fingers on triggers unless there’s a reason. We don’t know who else might be here.”

They found the first body ten yards inside the gate.

The man was Japanese, face-down in the dirt, a pistol just out of reach of his hand. The wound in his chest was neat and dark, the blood dried to a dull stain. There was no rifle near him, no helmet. Just a faded uniform and a cheap metal whistle around his neck.

“Looks like he did himself,” Harper said quietly. “Didn’t want to answer questions, maybe.”

“Or he didn’t want anyone to answer them for him,” Jack replied.

They moved past the body.

That was when the women stepped fully into view.

There were thirty-two of them.

At least, that’s what Jack wrote down later, when the paperwork began. Ages estimated between eighteen and forty. All Japanese, though a few had accents different from the others when they tried their English, and one tiny woman in the corner had eyes that made Doc guess she might have had mixed heritage.

They wore a scattered assortment of clothing. Stripped-down uniforms. Thin summer shirts that had once been white. Old army jackets with sleeves rolled up or rolled down so many times the cuffs were frayed away.

None of them came closer than ten feet. They stood in a semi-circle, watching the Americans carefully. Fear was there in some faces, but not the wild panic Jack had seen in other places. This fear was older, more tired, like they’d already run out of ways to be afraid.

Jack stepped forward, one hand up, the other far from his weapon.

“We’re American soldiers,” he said slowly. “You’re safe now. Do any of you speak English?”

The woman from the rain barrel moved a little closer. She nodded once.

“Little,” she replied. Her voice was hoarse, as if she didn’t use it often. “I was… student. Before.”

“Before what?” Lieutenant Harris asked, his tone gentle.

“Before… this.” She gestured vaguely at the camp, and Jack felt something cold slide under his ribs.

“My name’s Jack,” he said. “This is Doc. And that’s Lieutenant Harris. We’re here to help you.”

The woman studied him. Her eyes lingered on his face, his hands, his boots. Then she nodded again.

“I am Aiko,” she said. “We are… prisoners.” She touched her chest, then gestured to the others. “We were… taken. Long time.”

“How long?” Harris asked.

She frowned, thinking.

“Three years,” she said finally. “Maybe more. Hard to know.”

“Prisoners of your own army?” Private Lewis blurted out.

Jack elbowed him, hard. But Aiko had heard.

“Yes,” she said simply. “Of our army.”

Doc stepped forward. “We have food and medicine,” he said, very slowly. “We’d like to bring it in. Is that all right?”

The question seemed to surprise her. For a second, her face softened.

“Yes,” she said. “Please.”

The word almost broke him.

For the rest of that long afternoon, the camp looked more like a field hospital than a battlefield find.

Rations were opened, water boiled, bandages cut into strips. The women came forward in hesitant twos and threes, some leaning on others’ shoulders. Each carried invisible history in the way they walked.

Jack stood at the makeshift triage table Doc had set up and tried to keep his face neutral as he wrote.

“Name?” he would ask, or, when English failed, “Namae?” The others would repeat softly, some adding family names, some giving only first names as if guarding a secret.

“Pain?” he would ask, tapping an imaginary scale in the air. “Here?” He pointed to his head, his chest, his leg, his back.

Sometimes they would nod and make a small circle over a place. Sometimes they would just shrug, as if pain had become too constant to locate.

He was halfway through the line when it was Aiko’s turn.

She lowered herself onto the crate they were using as a seat with a careful, practiced motion. Jack was already watching closely, remembering what she had said. He saw the moment the mask slipped — a flash of raw hurt, quickly buried.

“You said it hurts when you sit,” he said quietly, as he wrote her name.

Aiko looked away toward the trees.

“Yes,” she said. “But is nothing.”

Jack shook his head. “Doesn’t look like nothing from where I’m standing.”

Doc crouched beside her, his tone calm and professional.

“I’m not here to judge you,” he said. “I just want to help you be more comfortable. Did someone hit you?” He tapped his own hip, then the edge of his backside, as delicately as he could. “Here?”

She hesitated. The yard suddenly felt too quiet. A couple of the other women had stopped their low conversations and were listening now, expressions tight.

“Many times,” Aiko said finally. “For small things. Speaking wrong. Standing wrong. Not smiling when… told.” Her lips thinned. “Sometimes more than hitting. But… hitting is easier to say.”

Jack wrote “repeated beatings; severe bruising” in the notebook. He knew it was incomplete, that a dozen words couldn’t hold the shape of what she’d just tried not to say. But it was all he could put on paper.

Doc’s jaw tightened. “I’m going to get you something for the pain,” he said. “May not fix everything, but it’ll help you walk and sit without wanting to scream. All right?”

She looked at him, as if weighing whether to trust this strange man with tired eyes and a medic’s bag.

“You are enemy,” she said slowly. “But you are… kind enemy.”

Doc smiled sadly. “I’m just a guy who hates seeing people hurt,” he said. “Uniforms don’t mean much when someone’s in pain.”

She studied him a second longer, then nodded.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

That night, after they’d radioed headquarters and set up a temporary perimeter, the argument started.

They were huddled in what had once been the guard shack. A map was spread on a crate, corners pinned down by canteens and the butt of a Colt. A lantern hung from a nail, casting harsh shadows.

Lieutenant Harris, Captain Luther, and a wiry military police captain named Briggs leaned over the map. Jack stood off to one side with Doc, arms crossed.

Briggs was the first to raise his voice.

“You’re telling me,” he said, jabbing a finger toward the barracks outside, “that those women are all from the enemy side. Nurses, clerks, maybe attached to some unit. And they’ve been here, under guard, for years?”

“Yes, sir,” Jack said. “That’s what they told us.”

“And you believe them?”

Jack hesitated. He could still feel Aiko’s gaze on him, serious and searching.

“Yes,” he said. “I do.”

Briggs snorted. “Sergeant, we’ve all heard stories. The enemy uses all kinds of tricks. Civilians, decoys, you name it.”

“With respect, Captain,” Doc said quietly, “that’s not a trick out there. That’s starvation, disease, untreated injuries, and women who sometimes can’t sit because of how badly they’ve been handled. I’ve patched up men who took machine gun fire with more color in their cheeks.”

Briggs’ jaw tightened.

“So their own people roughed them up,” he said. “You think our side is squeaky clean? Every army has its problems. That doesn’t change the fact that they wore the other side’s uniform and probably supported their war.”

Jack felt something hot spark behind his ribs.

“Some of them weren’t even in uniform when they were taken,” he said. “Students. Factory workers. One used to teach children. They got swept up, sent here, forgotten. That’s not ‘problems,’ sir. That’s… something else.”

Luther, who’d been silent, finally spoke up.

“I don’t like it either, Mercer,” he said. “But we can’t fix everything in one day. Our orders are to keep moving. We’re hunting a unit that’s still shooting at us.”

“So we just leave them?” Jack asked. “Hand them a few extra cans of beans and say, ‘Good luck, hope somebody remembers you exist’?”

“Watch your tone,” Harris murmured, but there was no real heat in it.

“I didn’t say leave them,” Luther replied. “But we have to decide who’s responsible for what. These women are technically enemy personnel. Once we report the camp, command might decide to treat them as normal prisoners of war. That means transfer to a larger facility, standard procedures, the whole machine.”

“And what happens to the story?” Doc asked. “The fact that they were held by their own side like this? Does that just get buried under forms and case numbers?”

Briggs exhaled sharply.

“Look,” he said. “I’m not made of stone. I saw their condition. It turned my stomach too. But you start making special categories — these prisoners are victims, these ones are not — and pretty soon you’re knee-deep in hearings and exceptions and finger-pointing. Our job is to maintain order.”

Jack took a slow breath, counting to three before he spoke.

“With respect, sir,” he said, “our job is also to tell the truth about what we find. If we walk out of here and write this up like any other camp, we’re helping erase what happened to them.”

The tiny shack suddenly felt crowded, air pressed thick between the walls. Outside, a dog barked once in the distance, then fell silent.

Luther looked tired. They all did. War wore people down in layers.

“All right,” he said finally. “Here’s what we’re going to do. Mercer, you and Reynolds gather detailed statements from as many of the women as you can. Dates, names, what happened, how they ended up here. Don’t push them past what they can handle, but get enough that nobody can say later this was just a misunderstanding.”

He turned to Briggs.

“Captain, you’re right that we can’t re-write policy in a jungle shack. But we can build a record that makes it hard for anyone to pretend this didn’t happen. Once we reach headquarters, this goes straight into the chain of command, with my full report attached.”

Briggs’ expression didn’t soften, exactly, but it shifted.

“And in the meantime?” he asked.

“In the meantime,” Luther said, “the women get food, medical care, and guards to keep them safe from anybody who thinks they’re an easy target — on either side of the wire. They’ve had enough of that.”

Briggs studied him, then nodded slowly.

“All right, Captain,” he said. “I’ll sign off on that. But you know this is going to start a storm, right? People are not going to like hearing that some of the worst things done out here weren’t done by our side or theirs, but by the system that was supposed to protect its own.”

Luther gave a humorless half-smile.

“Let it start,” he said. “Maybe it’s overdue.”

The argument didn’t end so much as settle into a tense, uneasy truce. But for Jack, something had shifted. This wasn’t just a strange side episode in a long and brutal campaign. It was a crossroads.

If they just marched away, these women would become another rumor, another “you wouldn’t believe what I saw once” at a bar back home. But if they wrote it down, if they looked it in the eye and didn’t blink, maybe — just maybe — the story would outlive them.

Over the next two days, Jack and Doc lived between notebooks and bandages.

Aiko helped translate when needed. Her English, though halting, was miles better than their Japanese. She moved from bunk to bunk, a quiet presence, speaking softly in her own language, then turning to Jack to relay as much as she could.

Sometimes she would pause, searching for a word, brow furrowed. “How to say…?” she’d ask, hands sketching shapes in the air, trying to convey something too complicated for vocabulary lists.

Jack would offer possibilities. Sometimes she would nod. Sometimes she would shake her head and say, “No. Too small word.” Then they would settle for something close, a phrase that fit in the notebook even if it didn’t quite fit the heart.

He learned there had been four guards once. Two had been transferred out months ago, as the war tide turned. One had died of fever. The last had shot himself when he saw the Americans coming.

He learned the women had been taken from different places — a university, a sewing factory, a clerical office in a port city, a village near an airfield. Their crimes, at least on paper, were vague: “questioning orders,” “not showing proper spirit,” “speaking out of turn.”

He learned that supplies had grown scarcer each year. Rations cut. Medicine used sparingly, then not at all. Punishments grew harsher as the guards grew more afraid — of superiors, of defeat, of someone reporting that they had “lost control” of their charges.

He also learned that the women had not been passive shadows in their own story.

Quiet acts of defiance gleamed like small lanterns in their accounts. Sharing food in secret. Singing songs softly at night when the guard stopped listening. Teaching each other to read, to count, to remember that they had once been more than numbers on a roster.

At first, some of the women refused to talk. They turned their faces to the wall or pretended to sleep when Jack approached.

He didn’t press. He would leave a cup of water near their bunk, or a bit of extra bread if he could get away with it, and move on. Sometimes, hours later, he would find the cup empty and the bread gone.

On the second night, one of the silent women — small, with hair cut so short it stuck up in uneven tufts — tugged at his sleeve as he passed.

“Write,” she said, eyes fixed on the floor.

“You want to talk now?” he asked.

She nodded once.

Her story came out in fits and starts. There were long pauses when she seemed to go somewhere else in her mind, then return, continuing in a monotone.

When she finished, Jack realized his hand was shaking. He set the pen down.

“Is it… okay?” she asked, glancing at the notebook as if it might explode.

“Yes,” he said, voice rough. “It’s more than okay. It’s important.”

She studied him for a long moment.

“I thought if I spoke, I would feel more… hurt,” she said. “But maybe it is… less heavy now.”

“Sometimes saying it out loud does that,” he replied. “Makes it real, but also less like it’s eating you from the inside.”

She gave him a ghost of a smile.

“Maybe,” she said. “Maybe it also makes you carry a little, too.”

Jack looked at the pages, filled with her cramped story in his blocky handwriting.

“I think that’s fair,” he said.

On the third day, a jeep rolled into camp carrying two officers from headquarters and a man in a crisp uniform with a clipboard. His hair was neatly cut, his boots clean despite the mud.

He introduced himself as Major Collins, from the legal branch.

As they walked through the camp, Collins’ face stayed mostly controlled, but Jack saw the crack in his composure when Doc gently helped a woman to her feet and she gasped, clutching the frame of the bunk, unable to straighten fully.

“What’s wrong?” Collins asked.

“She has deep bruising and old injuries,” Doc replied. “Never properly treated. Walking’s hard. Sitting’s worse.”

The woman tried to stand straighter, as if ashamed. “I am fine,” she insisted through Aiko. “Others are worse.”

Collins shook his head slowly.

“I don’t think ‘fine’ means what you think it means,” he said.

They gathered in the yard under a hazy sun. The women lined up loosely, looking from the new officer to Jack, as if trying to read their fate in the gap between uniforms.

Major Collins cleared his throat.

“I know you have many questions,” he began, speaking slowly and asking Aiko to translate. “For now, I can tell you this: you are under the protection of our forces. You will be moved from this place soon. You will have food, medical care, and the chance to rest.”

A murmur went through the group. Some of it sounded like relief. Some of it sounded like the quiet skepticism of people who had heard promises before.

Collins continued.

“I have read Sergeant Mercer’s notes,” he said, lifting the clipboard. “I have spoken with your medic, with the men who found you. I want you to know that your words are being recorded. What happened here will not be treated as a small matter or forgotten incident.”

He paused, searching for the right phrase.

“In war, many things happen that should never happen,” he said. “We cannot change the time before today. But we can decide what kind of people we will be after we know.”

Aiko translated carefully. When she finished, her own eyes were shiny.

One of the older women, lines etched deep around her mouth, raised a hand.

“So now we are… whose responsibility?” she asked.

“Right now?” Collins replied. “Ours. After the war? That will be harder to say. But our job is to make sure that when people write about this war, your part of it is not left out because it is inconvenient.”

Jack watched the exchange, feeling something loosen inside him. It wasn’t justice, exactly. Not yet. But it was the first step toward not being invisible.

Later, as the women drifted back to the barracks and the men to their positions, Collins pulled Jack aside.

“You did good work here, Sergeant,” he said.

Jack shrugged, suddenly uncomfortable.

“I just wrote down what they told me,” he said.

“You did more than that,” Collins replied. “Most people prefer their war stories simple. Good guys, bad guys, clean lines. You walked into a mess and refused to look away.”

Jack stared past him, at the sagging fence, at the guard shack, at the muddy yard where three years had been ground into the dirt.

“Truth doesn’t care if we’re comfortable,” he said. “It just cares whether we tell it or bury it.”

Collins nodded slowly.

“Remember that when you go home,” he said. “Because once you’re back there, people are going to ask you what you saw. And they’re going to want only part of the story.”

The convoy arrived at dawn on the fourth day — trucks with faded markings, canvas flapping like tired wings.

Loading the women was a slow, careful process. Some could climb up on their own. Some needed help, hands under their elbows, shoulders to lean on. A few had to be carried on makeshift stretchers, Doc walking beside them like a shepherd.

Aiko was one of the last to board.

She stood at the foot of the truck, looking back at the camp. Her face was unreadable, but her hands were fists at her sides.

Jack approached, helmet tucked under his arm.

“You ready?” he asked.

She nodded, then shook her head, then gave a small, frustrated laugh.

“I don’t know how to be ready for this,” she admitted. “I have been in that place so long. I almost forgot what ‘outside’ feels like.”

Jack glanced at the barracks. In the early light, they looked less like buildings and more like long, low scars on the earth.

“Outside’s not perfect,” he said. “But it’s bigger. And sometimes bigger is better than smaller, even if it’s still confusing.”

She smiled faintly.

“You will keep your promise?” she asked. “To tell what happened?”

He lifted the notebook slightly.

“Every page,” he said. “And when people get tired of hearing about it, I’ll tell them again.”

She studied him, then did something that surprised them both. She stepped forward and took his hand.

Her grip was light but steady.

“Many men came to this camp,” she said. “Most wore that uniform.” She nodded at the empty patch on her own sleeve where an insignia had once been torn off. “They said they were here to protect the country. But they forgot to protect the people.”

She squeezed his hand once.

“Do not forget,” she said.

“I won’t,” he replied.

She let go, then climbed into the truck, moving with that same measured care that said more about her pain than any words ever could.

As the convoy rumbled away, Jack and Doc stood at the edge of the road, watching until it disappeared around a bend.

Doc exhaled slowly.

“You know,” he said, “when I signed up, I figured the worst thing I’d see would be what the enemy did to us. I didn’t expect to be more shaken by what they did to their own.”

Jack nodded.

“Pain is pain,” he said. “Doesn’t care what language you speak or what flag’s hanging above the camp.”

For a long moment, they were both silent.

Then Doc glanced sideways at him.

“You okay?” he asked.

Jack thought of Aiko’s first words in the barracks. It hurts when I sit. Four simple words that carried whole chapters you couldn’t put in a field report.

“No,” he said honestly. “But I’m more honest than I was four days ago. That’s something.”

Years later, long after the uniforms were folded into drawers and the rifles put away, Jack Mercer sat at his kitchen table in Ohio, a cup of coffee cooling at his elbow, a stack of papers spread out before him.

The letter had arrived that morning, in a crisp envelope with an unfamiliar seal. Inside was a copy of an official report, thick and dry, full of phrases like “conditions inconsistent with military regulations” and “documented instances of excessive discipline and unlawful confinement.”

Tucked into the back, almost as an afterthought, was a separate sheet — a brief summary of testimonies gathered from “former internees held by their own military in a remote facility.”

The language was neutral, careful, stripped of emotion.

But Jack recognized the details.

A woman who had been punished for questioning a guard’s order. Another who had been detained for speaking her mind at a factory meeting. A camp where rations dwindled and discipline turned cruel as fear of defeat grew.

The report did not name the camp. It did not mention Aiko or any of the others by name. But it acknowledged, in the smallest of official ways, that they had existed and that what happened to them was wrong.

Jack leaned back, rubbing his eyes.

“Bad news?” his wife, Ellen, asked from the doorway.

He shook his head slowly.

“No,” he said. “Not bad news. Just… late news.”

She crossed the room, resting a hand on his shoulder.

“War again?” she asked gently.

He nodded.

“They finally wrote down something I saw a long time ago,” he said. “The words aren’t as strong as what I remember. But they’re there. In black and white.”

He tapped the report.

“They talk about a camp where women were held by their own side,” he said. “How they were treated. How some of them still can’t sit or walk right years later. How their courage in talking about it helped us understand that pain doesn’t always come from where you expect.”

Ellen squeezed his shoulder.

“You told me about them,” she said softly. “The women who said it hurt when they sat.”

He smiled faintly.

“Yeah,” he said. “That line’s stayed with me. It was such a simple way to say something huge.”

He picked up the report again, scanning the dense paragraphs.

“There’s going to be noise about this,” he said. “People who don’t want to hear that their side did something wrong. People who say we’re making it up or exaggerating. People who say we’re dragging up old wounds.”

“And what do you say?” she asked.

He looked out the window, where the afternoon light lay over the yard, gentle and warm — a world away from a mountain camp and a sagging fence.

“I say,” he answered slowly, “that if someone is still hurting when they sit, all these years later, the least we can do is not pretend we never saw.”

He thought of Aiko, of the way she had stood in the yard asking whose responsibility she was now. Of the women who had whispered their stories into his notebook, trusting that someone would carry them forward.

He thought of the argument in the guard shack, the fear in the faces of tough men when they realized the world was more complicated than they’d been told.

War had taught him many things: how to move quietly, how to read terrain, how to tell the difference between fireworks and artillery by sound alone.

But the camp had taught him something rarer: that courage sometimes looked like a woman standing up, wincing when she sat, and saying, in a voice barely above a whisper, “This happened to me. Please write it down.”

He folded the report carefully and slipped it into a folder with his old notebooks. The pages were yellowed now, edges curled, ink faded in places. But the words were still there.

As long as he was, he thought, he’d keep telling the story. And maybe, somewhere, one of the women from the camp would feel a weight lift just a little, knowing that their pain had not disappeared into silence.

He took a sip of his now-lukewarm coffee and smiled to himself.

“It hurts when I sit,” he murmured, trying the phrase out again in the quiet kitchen.

It still startled him, how such small words could shock hardened soldiers, crack the armor they wore around their hearts, and force them to see that the world was not divided neatly into victims and villains.

Some people were hurt by the enemy. Some were hurt by their own side. Some were hurt by both. And some were hurt most of all by the world’s desire to move on and forget.

Jack decided — again — that he wouldn’t be part of that forgetting.

He slid the folder back into the drawer, next to family photo albums and tax records.

Right there in the middle of ordinary life, tucked between school pictures and grocery lists, the story waited — not perfect, not complete, but stubbornly true.

And as long as those pages existed, so did they.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell That Could Punch Through a U-Boat’s Pressure Hull and Send It Down With One Hit in the North Atlantic Night

They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell…

End of content

No more pages to load