“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

The first time Lieutenant Jack Warren heard the phrase, it was delivered in a whisper so soft it barely made it across the dusty, ruined waiting room.

“It hurts when I sit.”

He didn’t catch it at first.

He was too distracted by the smell of antiseptic and damp plaster, by the sight of the cracked windows of the improvised clinic and the line of pale-faced German civilians—mostly women, a few old men—waiting on wooden chairs.

The war, as far as the maps in headquarters were concerned, was nearly over.

The 3rd Army had rolled past this small town on the Main River a week ago. The front line now lay miles to the east. Shellfire was something you heard about, not something you heard.

On paper, the town was “liberated.”

In reality, it was… something else.

The American command post squatted in what had been the mayor’s house. A white star sat awkwardly atop a stone fountain in the square. The church’s bells had been silent since the last artillery barrage knocked a chunk off their tower.

And this clinic—once a school, now a place where a harried German doctor in a threadbare coat and two American medics tried to make sense of the injuries the battle had left behind.

Jack, fresh out of the States barely eight months, had been made an MP lieutenant because he was calm, he kept his rifle clean, and someone in personnel had decided his pre-war law classes might be useful when the Army needed to sort out “civil affairs.”

He was still waiting for that usefulness to feel anything but theoretical.

Captain Meyers, the company commander, had sent him to the clinic with a simple order:

“Check on the medics. See what they need. Keep an eye on the locals. We’re supposed to be winning hearts and minds now, Lieutenant. Try not to start a war of your own.”

Jack had nodded, slung his carbine, and gone.

Now, standing just inside the doorway of the clinic, helmet tucked under his arm, he felt the eyes of the waiting room on him—suspicion and fear and something else he hadn’t yet learned to name.

The American medic, a lanky kid from Ohio named Henderson, spotted him and waved him over.

“Hey, Lieutenant,” Henderson said, lowering his voice automatically. “We could use more sulfa, if you can scrounge it. And bandages. And maybe a new roof.”

He glanced up at the water stains spreading like bruises along the ceiling.

Jack smiled.

“I’ll see what I can do about the first two,” he said. “The third will have to wait until someone in ordnance learns carpentry.”

He was about to ask how many wounded they’d treated from the last push when he heard it again.

“It hurts when I sit.”

This time, the words came with a choked sigh at the end.

He turned.

A girl—no, a woman, he corrected himself, though she couldn’t have been more than twenty—sat on one of the chairs, hands clenched in the fabric of her skirt.

She wore a coat too big for her and boots too small. Her hair was pulled back in a tight knot, a few strands stuck damply to her forehead.

Her friend—or sister?—sat next to her, eyes down, lips pressed thin.

The doctor, a gray-haired man with round spectacles and a tired face, stood beside them, with Henderson hovering.

“Was ist los?” the doctor asked gently. “What is wrong?”

The young woman swallowed.

Her German rolled over Jack’s ears like gravel.

He caught only fragments.

Pain.

Night.

Soldaten.

Henderson shot Jack a quick look.

“Sir,” Henderson said quietly, “you might want to hear this.”

Jack took a step closer.

The doctor hesitated, then nodded.

“These are your… how do you say… Polizeioffizier?” he said in careful English to the young woman. “You can tell them.”

She looked at Jack as if measuring him against something she remembered or feared.

Then she spoke again.

Slowly.

Carefully.

In German, at first, then in broken English, searching for words.

“It… hurts when I sit,” she repeated, cheeks flushing. “Here.” She gestured vaguely at her lower back, her hips, as if the exact place were too shameful to point to.

“From what?” Jack asked gently, though he already suspected.

The doctor cleared his throat.

“There have been… several cases,” he said. “Young women. Injuries not from shell fragments, not from accidents. From… rough handling.”

He looked away, embarrassed.

Henderson shifted his weight.

“You mean—” Jack began.

“Soldiers,” the doctor said quietly. “Your soldiers. At night. When they come into the houses for… drink, or fun.”

The word stuck like something sour on his tongue.

The young woman clenched her jaw.

“One came in,” she said in halting English, eyes fixed on a point somewhere over Jack’s shoulder. “He had… this.” She mimed a bottle. “He was… happy. Then… angry. He pushed. Hit. Then…”

She trailed off.

The doctor intervened.

“There is no need to describe in detail,” he said.

Jack’s throat felt dry.

He had expected to hear about looting. About fights in taverns. About black market cigarettes.

He had not expected this.

“Has this happened many times?” he asked.

The doctor nodded.

“In the last three nights, I have seen nine women,” he said. “Some old, some young. All with similar injuries. Some say nothing. Some say too much. All say…” He shrugged helplessly. “All say it hurts when they sit.”

The phrase landed in Jack’s mind with a weight heavier than any bullet.

He looked at Henderson.

Henderson looked away.

“I thought maybe it was some of the Russians,” Henderson muttered, ashamed. “You hear stories. But the Russians aren’t here.”

“No,” the doctor said. “These were Americans. We… we know the difference.”

The young woman’s friend, who had been silent, suddenly spoke up, German tumbling out in an angry flood.

The doctor translated.

“She says,” he said, “that one of them had a big white star on his shoulder. That he laughed when she cried.”

Jack clenched his fist around the wood of his carbine stock until his knuckles hurt.

He had seen men in his unit be rude, crude, even cruel to each other.

He had not seen—or had not allowed himself to see—what some of them might do when given a town full of people who could not fight back and a war that said they were the victors.

His mind flashed back to the orientation meeting in England months ago: a chaplain standing in front of a chalkboard, talking about avoiding “fraternization,” about maintaining discipline, about not letting victory excuse wrongdoing.

It had seemed abstract then.

Not now.

“Doctor,” Jack said slowly, “can you write down the names of these women? And any details they are willing to share—where they live, what uniform patches they saw, anything that might help us identify who did this.”

The doctor nodded.

“Yes,” he said. “Some do not want to speak. They are… ashamed. Or afraid you will blame them.”

He looked at the girl.

“She came because it hurts too much not to,” he added quietly.

Jack took out his notebook.

He wrote carefully.

Name.

Address.

Brief summary.

He tried not to think about how cold those lines would look later.

When he finished, he closed the notebook.

“I’m sorry,” he told the girls in slow, clumsy German. “We will… we will do something.”

He didn’t know yet what that something would be.

But he knew this:

If he walked out of that clinic and pretended he hadn’t heard what he’d heard, he would be no better than the men who had done it.

Back at the company command post, the air was warmer and thicker.

Cigarette smoke curled toward the ceiling. A pot of coffee boiled on a small stove in the corner, its smell stronger than the flavor.

Captain Meyers sat at a table with a stack of reports, his helmet pushed back on his head. His jaw had grown more stubble than regulation allowed in the last week, and his eyes had the slightly wild look of someone who slept more on maps than mattresses.

He looked up as Jack came in.

“Well?” he asked. “Henderson still whining for bandages and miracles?”

Jack remained standing.

“Sir,” he said. “The medics need supplies, yes. But that’s not why I came back so fast.”

He set his notebook on the table and slid it toward Meyers.

Meyers glanced down.

He read a few lines.

His expression changed.

From curiosity to irritation to something harder.

“Damn it,” he muttered.

He read further.

“Damn it,” he said again, louder this time.

He looked up at Jack.

“How many?” he asked.

“Nine that came to the doctor,” Jack said. “In three nights. He thinks there are more who haven’t.”

Meyers swore under his breath in a way that had nothing to do with shell fragments or officers above him.

“How sure is he?” he demanded. “Could some of these be… I don’t know… situations they later regretted? Did they see the men clearly? Could they be putting this on us because we’re the ones in town now?”

Jack shook his head.

“This isn’t pillow talk gone sour, sir,” he said bluntly. “They’re bruised. They’re torn up. One of them could barely walk. The doctor isn’t guessing. He’s not our friend, but he’s not stupid.”

He hesitated.

“And frankly,” he added, “we both know some of our boys have been drinking hard and running loose. This would not be the first unit in history where victory got ugly.”

Meyers rubbed his temples.

“This is the last thing we need,” he said. “Division wants us to keep moving east. Battalion wants us to secure the crossings. Regimental wants patrols. And now this.”

He flipped the notebook shut and slapped his hand on it.

He called for his platoon leaders.

Within minutes, the cramped room was full of officers and senior NCOs, steam from the coffee mingling with the smell of damp wool.

Meyers laid out what Jack had heard.

For a moment, the room was very quiet.

Then the tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng.

Lieutenant Grady, a barrel-chested Southerner with a habit of chewing cigarette filters, went red in the face.

“You’re telling me,” he exploded, “that after all we’ve been through—Kasserine, the Bulge, crossing that damned river—we are now going to hold court for a bunch of Kraut girls complaining that our boys were too rough?”

“That ‘bunch of Kraut girls’ are civilians under our control,” Jack said evenly. “We’re occupiers now, like it or not.”

“They’re the enemy,” Grady shot back. “Or did you forget who shot at us from those windows last week? Maybe some of our boys are just evening the score.”

“That’s not ‘evening the score,’” Sergeant Rossi, a compact New Yorker with dark eyes and a face older than his years, snapped. “That’s taking a war you’re supposed to fight with a rifle and dragging it into a bedroom.”

Some of the officers shifted uncomfortably.

Captain Meyers held up a hand.

“Enough,” he said. “Nobody’s saying this is going to be easy. But we have a problem, and we will address it like soldiers, not like a mob.”

He nodded at Jack.

“Lieutenant Warren here has brought me the first concrete report we’ve had,” he said. “I don’t like it. But I like the idea of being the kind of outfit that shrugs this off even less.”

Grady shook his head.

“What do you want us to do?” he demanded. “Chain every private to his bunk at night? Post MPs at every farmhouse?”

“Start with your own men,” Meyers said. “Talk to them. Make it absolutely clear that anyone caught forcing themselves on civilians will be treated as a criminal, not a hero.”

Grady snorted.

“And if they say it was… willing?” he asked. “You want us to play judge, jury, and mind-reader between some German girl and a GI who swears she was glad he came along?”

Rossi looked at him.

“Maybe we start by listening,” he said quietly. “We didn’t like it when nobody listened to us about anything back in Africa. Maybe we give them at least that much.”

Jack thought of the girl’s words—“It hurts when I sit”—and felt his jaw tighten.

“We’re not going to solve this by pretending it isn’t happening,” he said. “We can’t protect every woman in this town. We can’t vet every interaction. But we can make an example if we catch someone in the act. And we can let our men know that someone is watching.”

Meyers nodded.

“First step,” he said, “is information. Lieutenant, I want you and a couple of MPs to quietly canvass the medics, the chaplain, and any trusted locals. Find out where this is happening most. Time of day, locations. See if any of the descriptions match our units.”

He looked around the room.

“Second,” he went on, “platoon leaders, you will remind your men what the rules are. No forced contact. No abuse. We are not here to do what we fought the Germans for doing in other countries. Is that understood?”

Most nodded.

Grady did, eventually, though his expression remained mulish.

“And third,” Meyers concluded, “we set up night patrols. Not just to watch for straggler Germans—but to watch for our own who think the war is a ticket to anything they want. If you see anyone out past curfew without a good reason, you bring them in. I don’t care if it’s the division commander’s nephew.”

Rossi gave a short, sharp nod.

Grady muttered something under his breath about “boys blowing off steam.”

Meyers heard it.

“So help me, Lieutenant,” he said, his voice gone cold, “if your idea of ‘blowing off steam’ includes assaulting civilians, I will personally arrange for you to spend the rest of the war in a cell. Don’t test me on this.”

The room went quiet again.

Then, slowly, the officers filed out.

Outside, the sounds of a town trying to pretend it could return to normal drifted in: chickens clucking, a cart rattling along cobblestones, someone’s radio playing a scratchy waltz in a language that was not yet forbidden again.

Jack stayed behind.

“That could have gone worse,” he said.

Meyers gave a tired smile.

“Could have gone better too,” he replied. “But we’re in the business of doing what’s possible, not what’s perfect.”

He picked up Jack’s notebook again.

“You did the right thing,” he said quietly.

Jack wasn’t so sure.

It felt less like doing right and more like dragging something filthy into the light and hoping it didn’t splatter too much.

The first patrols weren’t glamorous.

Jack took one of them himself, because he refused to ask his men to walk alleys at night if he wouldn’t.

He and Rossi and two privates moved slowly through the darkened streets, boots soft on cobblestones, breath visible in the cool air.

Most houses had their shutters drawn.

Where there were lights, they were dim.

Every so often, they heard laughter—American voices, German voices, sometimes both.

They did not rush toward every sound.

They didn’t have the right, nor the desire, to police every interaction.

What they were listening for were different sounds:

Shouts.

Crashes.

Crying.

In the second week of patrols, they heard it.

A shout.

A crash.

Then a woman’s voice, raised in something that was not laughter.

They followed the sound to a half-collapsed barn at the edge of town.

Inside, by the light of a single lantern, two American soldiers had cornered a girl against a bale of hay.

Her dress was torn at the shoulder.

Her hands were clenched fists.

She was saying “Nein” over and over in rising tones.

One of the men, drunk enough to sway, had one hand on her arm and the other fumbling at his belt.

The other laughed and picked up the bottle.

“Evening, boys,” Rossi said quietly, stepping into the light with his carbine in the crook of his elbow.

The two men froze.

The drunker one blinked.

“Hey, Sarge,” he slurred. “We were just—”

Jack stepped in behind Rossi.

He didn’t shout.

He didn’t need to.

“Hands off the girl,” he said. “Now.”

The sober-er of the two men hesitated.

Then, slowly, he let go.

The girl bolted sideways, clutching her torn dress, and ducked behind Jack and Rossi as if they were the lesser of two evils.

Jack could feel her trembling against his back.

He did not turn around.

He kept his eyes on the men.

“You’re out past curfew,” he said. “In a prohibited area. With a civilian who clearly did not invite you. You know what that looks like?”

The drunk one opened his mouth to protest.

The other cut him off.

“We weren’t going to hurt her,” he said quickly. “We were just having a little fun. She said—”

“She said ‘no,’” Rossi snapped. “We heard it.”

The drunk one rolled his eyes.

“She’s just a Kraut,” he muttered. “Lighten up, Sarge. War’s nearly over. We earned—”

Rossi moved so fast Jack barely saw it.

He stepped in, jammed the butt of his carbine into the man’s gut just hard enough to fold him, not enough to break anything.

“Finish that sentence,” Rossi said evenly, “and I’ll make sure you never sit comfortably again either.”

The man wheezed.

The other took a half-step back.

“Lieutenant,” Rossi said without looking away from them, “what are your orders?”

Jack thought of the clinic.

Of the girl’s whisper.

Of the argument in the command post.

Of Meyers’s tired face.

“Get their names,” he said. “Their unit. Then march them back to the CP. We’ll let the Captain decide what to do officially. Unofficially, these two don’t leave a stockade again until they’re on a boat.”

The drunk one spluttered.

“You can’t—” he started.

“I can,” Jack said. “And I will. You think we crossed an ocean and bled across half this country so you could do here what the Germans did in Poland and France? Think again.”

The sober-er one looked stricken.

“I didn’t touch her,” he said, but his denial was weak.

“You didn’t stop him either,” Rossi replied. “That’s not much to brag about.”

The girl, still trembling, slipped out the barn door.

Jack let her go.

He would not drag her back into a situation she clearly wanted to flee.

Outside, as Rossi and the privates marched the two soldiers away at bayonet point, Jack paused.

He leaned against the barn wall, closed his eyes, and let himself feel the weight of it.

This was not why he had joined.

He’d thought he’d be facing tanks, not this.

But the war was giving him what it had, not what he’d imagined.

He pushed off the wall and followed the patrol back to town.

The company handled the incident internally at first.

Meyers confined the two soldiers to quarters, then arranged for them to be sent to the rear for formal charges.

The legal machinery would grind slowly.

Jack didn’t know if they’d see a court-martial or a quiet transfer and a nasty mark in their files.

He did know word spread among the men:

Someone had been caught.

Someone had been punished.

Suddenly, the idea that “blowing off steam” at the expense of the locals might carry consequences seemed less theoretical.

A few weeks later, a colonel from division provost marshal’s office arrived and asked questions of his own.

“How widespread?” he asked Jack. “How often? How many reports?”

Jack showed him his notebook.

The colonel read silently for a long time.

Then he closed it.

“This is useful,” he said. “Ugly. But useful.”

He looked at Jack.

“You’re not the first MP officer to stumble into this,” he said. “You won’t be the last. Get used to the idea that your job is going to feel like sweeping the ocean with a broom.”

Jack bristled.

“Sir,” he said, “with respect, ‘get used to it’ is not a plan.”

The colonel smiled thinly.

“No,” he said. “It’s not. The plan is: document, deter, prosecute when possible, and don’t lie to ourselves about who we are.”

He sighed.

“The Russians have their own… approach,” he added. “The Germans, earlier in the war, had theirs. We like to think we’re better. Some days we are. Some days… we’re just human in ugly ways.”

He put a hand on Jack’s shoulder.

“You did the right thing,” he said. “Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Men like you give us a fighting chance of being the kind of army we say we are.”

Jack wasn’t sure he believed that.

But he took it anyway.

A ration of meaning in a world that often served less.

Years later, when the war was over and Europe had been divided into zones and memories, a German woman in her seventies sat in a café in Frankfurt and told her granddaughter a story.

The girl, born long after the occupation had ended, had asked a question after a history lesson at school:

“Oma, what were the Americans like? Were they all good? All bad?”

The old woman stirred her coffee.

“There were many,” she said slowly. “Some kind. Some cruel. Most just… boys too young to be there.”

She paused.

“I remember one,” she added. “He came to the clinic one day, when I was young. I could not sit without pain. He listened. His face went white. He took notes. Later, another came to our barn, when some of his men thought they could take whatever they wanted. He stopped them.”

She shrugged.

“Do those two men erase the others?” she asked. “No. Do the others erase those two? Also no. That is the problem with war. It fits many truths into the same uniform.”

Her granddaughter frowned.

“So,” the girl said, “they saved you?”

“Not exactly,” the old woman replied. “They did their duty. A duty they were not trained for, but which fell on them anyway. It hurt when I sat for a long time after. But it hurt less knowing that at least someone on their side said: ‘This is wrong.’”

The girl nodded slowly.

She didn’t fully understand.

She had never had to.

That was, perhaps, the best verdict anyone could hope for out of such stories.

That the people who came after would not know the exact feeling of “it hurts when I sit”—only the echo of what it meant, and the knowledge that some men chose to make it sweeter, others more bitter, and that those choices mattered.

For Jack, sitting on a porch in Ohio years later, watching his own children argue over a toy with a seriousness that felt almost funny, the memory came back sometimes.

The smell of the clinic.

The girl’s whispered phrase.

The barn.

The patrol.

The arguments in the command post where grown men who had faced artillery and machine guns now faced something less visible and somehow harder.

When they asked him, in simpler conversations, “What was the war like?” he could have told them about battles, about maps, about tanks and planes.

Sometimes he did.

Sometimes, when they were older, he told a different story.

About an empty line.

A girl who could not sit.

Men who thought victory entitled them to whatever they wanted.

And about the moment he realized that “treating the enemy” was not just about how you shot at them when they had rifles.

But how you behaved when they didn’t.

He never used the phrase “it hurts when I sit.”

That belonged to someone else.

But he carried its weight.

It was part of the war he had brought home inside his skull.

The part that didn’t show up in parades or on medals.

The part that mattered anyway.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

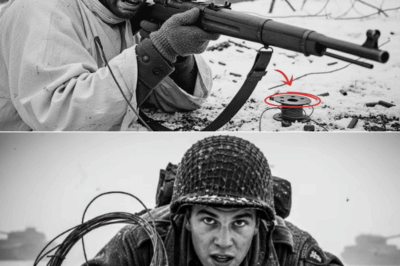

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell That Could Punch Through a U-Boat’s Pressure Hull and Send It Down With One Hit in the North Atlantic Night

They Laughed at “Ice Bullets From the Colonies” – Until a Quiet Team in Halifax Built a Secret Canadian Shell…

End of content

No more pages to load