How One Broken Man Turned a Wounded Nation Into His Mirror: Inside the Fear, Hope, and Mass Psychology That Allowed Hitler to Rise and Hold Sway Over Tens of Millions

In the spring of 1929, long before posters with a small dark figure would cover Germany’s walls, Anna Weiss was grading papers in a quiet classroom in Munich.

She taught history at a modest secondary school. Her students were restless, bright, and poor. Many came to class hungry. Some had fathers who still woke up screaming from memories of trenches and gas. Others had mothers who waited in line for bread that cost ten times what it had the month before.

On the day the American stock market crashed, Anna did not know that events thousands of miles away would help reshape her students’ future, and the future of Europe. She only knew that her country felt tired and angry—like a huge machine running on fumes.

“We lost the war,” her colleague Friedrich said that afternoon in the teachers’ lounge, lighting a cigarette with shaky hands. “We pay and pay and pay. Our veterans beg on street corners while foreign visitors sit in the best cafes. And our leaders do nothing.”

Anna stared at the map on the wall. The borders of Germany had shifted again, like an outline drawn and erased by a distant hand.

“We signed the treaty,” she replied. “We bear responsibility. We cannot just blame the world.”

Friedrich shook his head.

“You don’t understand,” he said. “People don’t want nuance. They want someone to tell them who took their future—and how to get it back.”

He had no idea how right he was.

1. A Nation Looking for a Story

By 1930, Germany was deep in crisis. Millions were unemployed. Families burned furniture to stay warm. Children wrapped newspapers around their legs as makeshift socks.

Anna saw it in her classroom: students whose eyes glazed over when she spoke of ancient Rome or the French Revolution. Their history was not in textbooks—it was in empty cupboards and eviction notices.

One day, she assigned an essay: “What is the most important thing Germany needs now?”

The answers chilled her.

“We need order.”

“We need a leader who is not weak.”

“We need to be proud again.”

“We need someone who will stop our enemies.”

The word enemies was underlined several times in different papers. None of the students defined it clearly. It was an open space waiting to be filled.

People do not just want food and jobs, Anna thought. They want a story. A story in which they are not victims, but heroes. A story that makes suffering meaningful.

In beer halls and on street corners, a small, intense man with piercing eyes was already telling that story.

2. The First Time She Heard the Voice

It was Friedrich who convinced Anna to go hear him.

“Just once,” he said. “If you want to understand what’s happening in this country, you need to see it.”

They went to a large hall on the outskirts of the city. The air smelled of smoke and sweat. Men in brown shirts stood near the doors, chests puffed out, boots polished. There were flags, symbols, and banners everywhere, turning the room into a sea of color.

Anna felt uneasy.

“This is a political rally,” she said. “I thought it was a speech.”

“Speeches are the new battles,” Friedrich replied. “You’ll see.”

When Adolf Hitler walked onto the stage, there was a moment of near-total silence. He was smaller than Anna expected, almost unremarkable—until he started speaking.

He did not begin with shouting. At first, his voice was almost conversational.

He spoke of hunger. Of the humiliation of defeat in 1918. Of treaties signed under pressure. Of millions of Germans who felt abandoned.

“We are not the villains of the world,” he said. “We are a proud people who have been betrayed.”

Ripples of agreement moved through the crowd.

Anna could feel it—the emotional connection. He was not just giving facts; he was giving feelings a shape and a target.

Then his voice rose. He pounded the podium. He named enemies—inside and outside the country. He promised to restore greatness, to create jobs, to protect “true Germans,” to crush those who “poisoned” the nation.

Friedrich leaned over and whispered:

“He talks like he knows what people dream at night.”

Anna did not cheer. She watched.

She saw faces transformed—eyes shining, jaws clenched, hands reaching up in salute. Men who had arrived slouching now stood tall. They were no longer just factory workers or jobless veterans. For a moment, they were part of something huge.

Hitler was not just giving a speech.

He was offering identity.

3. The Psychology of “We”

In the weeks that followed, Anna read everything she could about mass persuasion. She discovered that people are easier to move in groups than alone. Fear multiplies in crowds—but so does hope.

She noticed patterns in Hitler’s approach:

He made problems simple and solutions dramatic.

He repeated phrases until they felt like truth.

He framed every issue as us vs. them.

He presented himself as the only one who truly understood.

Where others offered policies, he offered belonging.

It is difficult to resist someone who promises to transform your shame into pride.

Anna talked to her students about critical thinking, about checking sources, about the danger of simple answers.

But outside the classroom, posters multiplied like weeds. They showed Hitler not as a small man, but as a giant figure staring into the distance: decisive, strong, almost glowing.

In reality, he was just a politician with a troubled past and a talent for performance.

In the public story, he was becoming a savior.

4. The Election That Wasn’t the End

In 1932, Germany was torn between many parties. The parliament was fragmented. Governments rose and fell like sandcastles destroyed by tides.

Hitler’s party did not win a majority—but they won enough.

They won enough to be impossible to ignore, enough to dominate conversations, enough to make other politicians think:

“Maybe we can use him. Maybe we can control him.”

Anna heard this argument repeated in cafes and university halls.

“He is extreme, yes,” said one local official, stirring his coffee. “But we can guide him. Harness the energy of his followers. Use his popularity to stabilize the country.”

This was the fatal miscalculation.

People often believe they can control a rising figure because they know his weaknesses. They forget that his supporters do not see those weaknesses—only his promise.

In January 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor.

Some cheered. Some panicked. Many shrugged and said:

“Let’s give him a chance. Things are already bad. How much worse can it get?”

Those words echo through history more often than we like to admit.

5. Creating Crisis, Then Offering “Order”

Shortly after Hitler took power, a dramatic fire destroyed the parliament building. The flames lit up the Berlin sky like a warning.

Official statements blamed a supposed plot against the nation. The new government responded with “emergency measures.”

New laws were rushed through. Civil rights were suspended. Opponents were arrested “for security reasons.” Newspapers were warned. Courts were pressured.

Anna read the decrees in the newspaper, her fingers trembling.

“They are using fear as a tool,” she told Friedrich. “When people are afraid, they accept things they would never accept in calm times.”

He nodded, but his eyes betrayed doubt.

“Some say these steps are necessary,” he replied. “There are dangerous elements. Maybe strong measures will bring stability.”

That was the genius—and the horror—of the strategy:

Exaggerate threats.

Create or highlight crisis.

Frame yourself as the only shield.

Demand extraordinary powers “temporarily.”

Temporary powers have a way of becoming permanent.

Hitler did not seize total control in one dramatic night. He took it piece by piece. One law here, one jail cell there, one silenced editor, one dismissed judge, one banned party.

People noticed. But many told themselves:

“It won’t touch me. I am not involved in politics. I am just trying to live my life.”

They misunderstood something critical: you do not need to care about politics for politics to care about you.

6. The Power of Silence

By 1934, Anna’s classroom looked different.

Some students now wore party youth uniforms on special days. They marched in parades and sang songs about strength and sacrifice. They repeated slogans with the bright certainty of those who have been given a simple moral map: we are good, they are bad.

One afternoon, she noticed that a usually talkative student, Lukas, was quiet.

“Is something wrong?” she asked after class.

He hesitated.

“My father says we should not talk about politics at home,” he whispered. “My older brother joined the youth organization. My father is… worried. But he says we must be careful what we say, even to friends.”

Fear had entered living rooms.

On the street, Anna saw neighbors who used to chat freely now nodding stiffly and moving on. People avoided certain topics, certain names.

You do not need everyone to support you enthusiastically to control a country. You just need enough people to:

Support you loudly, or

Oppose you quietly, or

Look away.

Silence is not neutral.

It is a space where power grows.

Hitler understood this. His government rewarded enthusiastic followers, tolerated the cautiously obedient, and crushed the defiant.

Over time, many people found it more comfortable to drift into the second group.

7. Changing Reality with Words

Language in Germany began to shift.

New terms appeared in newspapers and radio broadcasts: terms that made complex decisions sound natural and necessary.

Violent actions were called “measures.”

Crackdowns were called “security operations.”

Discrimination was presented as “restoring balance.”

When minority communities were targeted—forced out of jobs, insulted on walls, attacked in the street—the official line framed it as “correction” or “self-defense.”

Words did not describe reality; they reshaped it.

Anna noticed subtle changes even in school instructions. History textbooks were revised. Certain chapters disappeared, replaced by glowing stories of German destiny and loyal obedience.

Her lesson plans were questioned.

“You must align with the new curriculum,” the principal told her one day, avoiding her eyes. “We are all expected to teach in a way that supports national unity.”

He slid a thick envelope onto her desk. Inside were guidelines full of underlined phrases about loyalty, pride, and suspicion toward “undesirable influences.”

“This is not history,” she said softly. “This is theater.”

“I know,” he replied, almost inaudible. “But I have a family.”

That sentence became a shield many used to excuse their cooperation.

8. The Mechanisms of Control

By the late 1930s, Hitler’s image was everywhere. Portraits hung in classrooms, offices, shop windows. Schoolchildren learned songs praising him. People were taught to celebrate his birthday as if it were a national holiday.

Control operated on several psychological levels:

Hero Worship

Hitler was presented not as a politician, but as a near-mystical figure. Photos showed him touching children’s heads, petting dogs, staring bravely into the distance. The message: he cares, he sees farther, he is different from the corrupt old leaders.

Social Proof

Mass rallies created powerful illusions. When you stand in a stadium with thousands of people all cheering the same name, it is hard to imagine you might be wrong and they might be wrong too. The crowd becomes a mirror that tells you: You belong. You are part of something unstoppable.

Conformity Pressure

People learned to read cues: who saluted quickly, who hesitated, who did not. Not joining in seemed dangerous. Many saluted not out of love, but out of fear—or simply out of habit. Over time, habit feels like belief.

Scapegoating

Every problem had an easy explanation: traitors within and enemies without. Minority groups, political opponents, free thinkers—all were labeled as threats. Blaming “them” spared people from looking at their own society, their own responsibilities.

Gradual Escalation

At first, it was just harsher language. Then boycotts, then firings, then laws, then camps. Each step prepared the mind for the next. People said, “It’s not that bad,” at every stage—until it was.

Anna watched all this and felt, at times, like someone standing on a beach, watching the water withdraw before a tsunami.

She tried to resist in small ways: slipping banned authors into her students’ hands, encouraging questions, reminding them that history is full of leaders who seemed invincible until they were not.

But the machinery was vast. And it was powered not only by Hitler himself, but by millions of tiny choices made every day by ordinary people.

9. One Man—But Not Only One Man

To say that Hitler “controlled 80 million people” is both true and incomplete.

He was the spark, yes. His personality, his traumas, his resentments, his strange charisma—all were crucial. Without him, the precise shape of events would have been different.

But sparks only become wildfires when the forest is dry.

Germany in the 1930s was dry tinder:

Wounded pride from a lost war.

Economic collapse and unemployment.

A weak democracy with too many factions.

Old prejudices looking for modern justification.

A population unused to long-term democratic habits.

Hitler did not hypnotize a peaceful, content people.

He offered a violent, simple story to a wounded, complicated society.

Others could have pushed back more strongly: judges who chose to stay, generals who chose loyalty to law, religious leaders who chose silence, neighbors who chose comfort over courage.

Some did resist. They were imprisoned, exiled, or killed. Their names appear in smaller print in history books, but their choices were real.

Hitler’s power was terrible, but it was never magic.

It was a structure built from:

Fear,

Hope,

Anger,

Myth,

And millions of acts of obedience—some loud, some quiet.

10. After the Collapse

Years later, after cities lay in ruins and the crimes of the regime were exposed to the world, Anna stood with a group of former students in what remained of their schoolyard.

Some wore uniforms. Some had lost limbs. Some had lost entire families.

“How did this happen?” one of them asked, voice breaking. “How did we let one man take everything?”

Anna looked at them, their faces harder now, older than their years.

“It was never just one man,” she said. “He opened the door. But others held it for him. Some out of conviction, some out of fear, some out of indifference.”

She paused, choosing her words carefully.

“He understood something dangerous about people: that we long to belong, to feel strong, to have simple answers when the world is complicated. He promised those things. Enough of us accepted the offer—or refused to question it.”

One of the younger ones frowned.

“So is it hopeless?” he asked. “Are people always like this?”

“No,” Anna replied. “If that were true, history would be only stories of cruelty. But it also holds stories of those who refused. People who hid their neighbors. People who spoke when everyone else whispered. People who risked their lives to say: No. Not in my name.”

She looked at the shattered windows of the school.

“The lesson is not that we are helpless,” she said. “The lesson is that we are responsible. The next time someone offers easy enemies and promises to make you proud by teaching you to hate—ask questions. Refuse to cheer on command. Remember that the desire for a strong leader can make us weak if we stop thinking.”

They stood in silence, the wind whispering through broken bricks.

History, Anna knew, does not repeat itself exactly.

But the psychology that enabled Hitler’s rise lives wherever people feel humiliated, afraid, and desperate for a savior.

The question is not just: How did one man control 80 million people?

The deeper, more urgent question is:

How can we, in any time and place, make sure that no one ever does it again?

She did not know if her words would echo in their lives. But she spoke them anyway.

Because every mind that refuses to surrender to blind obedience is one less stone in the foundation of tyranny.

And that, she believed, was where real vigilance begins.

THE END

News

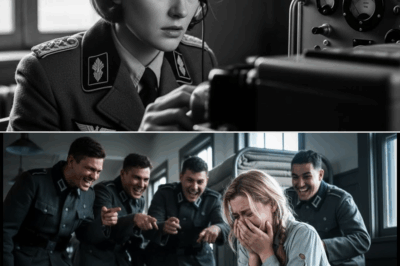

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

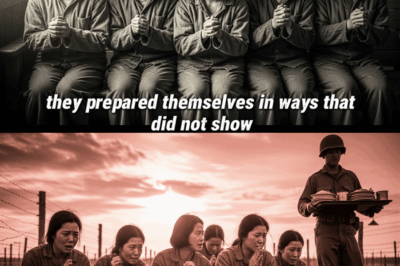

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

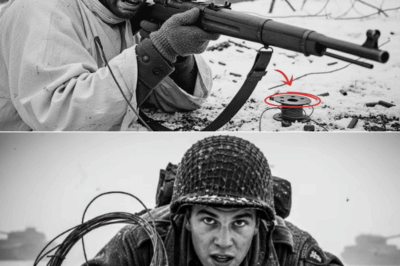

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load