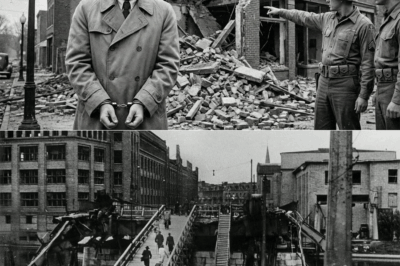

How German Women POWs Froze When an American Sergeant Ordered “Face the Wall…”, Why They Started Crying at the Sound of English Behind Them, and How That Moment Became a Lifetime Argument Over Fear, Guilt, and What the Order Really Meant

The first time they heard English behind them and the words “Face the wall…” in clipped, accented German, more than one woman thought:

This is how it ends.

Not in a courtroom. Not in a hospital. Not in some distant, tidy archive entry.

Here. In a damp brick hallway, under buzzing lights, her nose inches from peeling plaster.

“An die Wand. Face the wall,” the American sergeant said again, louder.

His accent turned “Wand” into something like “Vund,” but the meaning was clear enough.

Elisabeth König’s legs went weak.

There were eight of them, lined up in the corridor of a requisitioned factory building that now served as the camp’s administrative center. Their hands were empty. Their paper identity tags swung gently from string around their necks.

Behind them, boots scuffed.

Metal clinked.

Someone’s breath came in short, sharp bursts.

It was not the words alone that unraveled them.

It was everything those words carried.

Elisabeth’s mind filled in details that weren’t there: the barked order, the click of bolts drawn back, the “present arms” she’d heard in stories whispered late at night when no senior nurse could shush them.

“Face the wall,” she had once heard a fellow prisoner say, eyes blank. “That’s what they told my cousin in the prison in Cologne. There was no trial. Just that. And then shots.”

Now, pressed up against a yellowed wall in a town whose name she barely knew, she tasted metal in her mouth.

Her eyes stung.

She had promised herself, back in the first weeks of captivity, that she would not cry in front of them. Not in front of the enemy. Not if she could help it.

Her eyelids did not care.

Tears slid down her cheeks anyway.

Beside her, Lotte—the youngest of their group, barely twenty—was already sobbing, silently at first, then in small, helpless hiccups.

“Bitte,” someone farther down the line whispered. “Please…”

The American voices behind them kept coming, indifferent to the rising panic.

“Jones, you take that one. Carter, second from the left. We do this neat. No fuss.”

“Yessir.”

“Keep your hands away from your belts, ladies,” another voice called in clumsy German. “Hände weg. Don’t move.”

Hands shot up instinctively.

Elisabeth pressed her palms flat against the wall.

So this is it, she thought. No priest. No letter home. Just brick and boots and the echo of English.

She thought of her mother’s hands, tying her hair back before school. Of the smell of bread in their village bakery. Of the way the world had shrunk from fields and sky to bomb shelters and sirens and then to fences and foreign voices.

She did not think of the hospital where she had worked in the last years, the wards with their strict paper charts and stricter whispers about who deserved what treatment. She had learned, since capture, that thinking about that made her chest too tight.

Behind her, a weapon was shifted.

She flinched.

Someone to her right whispered, “Our families will never know where we fell.”

“Stop it,” hissed Gertrud, the oldest among them. “Don’t give them your death before they take it.”

Her voice shook.

Behind them, a small argument broke out in English.

“Sir, they’re crying.”

“They’ll be fine. Just get it done.”

“This seems a bit harsh, don’t you think?”

“We’re not hurting them. We’re searching them.”

The word slid across the language barrier in pieces.

Search.

Durchsuchung.

Not erschießen.

It took a moment for that to land.

“Wait,” Elisabeth whispered. “Did he say… ‘search’?”

Lotte gulped.

“I don’t know,” she hiccupped. “I don’t… I can’t…”

Then someone touched her.

Fingers, not on her neck or her back, but on her shoulder.

Light. There.

She jolted as if struck.

“Don’t touch—” she began, German and English tangling.

“Ma’am,” a voice said right by her ear, softer than the barked orders. “I’m going to pat you down. I’m looking for knives. Hidden things. That’s all. We’re not… This isn’t… You understand?”

The German stalled on his tongue, approximate and clumsy.

But the tone carried.

He was not shouting.

He sounded almost… embarrassed.

Her breathing hitched.

Around them, the wall remained solid.

No shots came.

The boots behind them shifted, closer now, not in a military cadence but in the uneven shuffling of men trying not to slip on a damp floor.

The hands that ran lightly over their sides, their sleeves, their belts were quick and impersonal, tapping for hard edges, for metal instead of flesh.

“Nothing,” someone said. “Next.”

“You can turn now,” the softer voice said.

Elisabeth did, slowly.

The face that greeted her was not what her fear had painted.

The American sergeant in front of her was older than she’d expected, his skin leathered from sun that had not shone in her country for months. His eyes were tired. His hands, when he pulled them back from her shoulders, shook a little.

“You are not… shooting us,” she said in halting English.

He blinked, taken aback.

“No, ma’am,” he said. “We’re not shooting you. We’re getting you processed. Quarantine. New barracks. Paperwork. Boring stuff.”

Behind his shoulder, the other women still stood rigid, some with tear tracks on their cheeks, some with their mouths set in hard lines.

The sergeant glanced past Elisabeth’s head, taking in the damp eyes and white knuckles.

He realized, belatedly, what “Face the wall” had sounded like to people who had spent the last few years overhearing rumors instead of instructions.

“Ah, hell,” he muttered under his breath. Then, louder, in clumsy German: “Nobody… nobody shoot. Okay? No schießen. Just check. Then Kaffee. Soup.”

His pronunciation mangled “Kaffee” into something like “Kaffi.”

The women stared at him.

One gave a short, disbelieving laugh.

It broke the tension like a glass hitting a stone floor.

Somewhere down the line, someone started crying harder, out of relief this time.

The misunderstanding was painfully simple in its anatomy.

On the American side, “Face the wall” was routine—a way to keep prisoners from watching where weapons were, a basic precaution before a search. The sergeant had said it on three continents now, to men who rolled their eyes and complied, to men who hissed insults over their shoulders, to men who already smelled of defeat and fear and sweat.

It had never, in his mind, been an order for execution.

On the German women’s side, “Face the wall” was loaded.

It was a phrase that had seeped into their consciousness in half-heard stories and sudden silences. A cousin’s letter that had stopped in the middle. A neighbor who had been taken “for questioning” and never came back. A doctor’s assistant who had whispered, “They lined them up and told them to look at the bricks.”

It had been the last thing some people heard.

Now, when the order came from a foreigner in a foreign building under a foreign flag, all of that history flooded in at once.

It didn’t matter that this wall had no bullet holes.

It didn’t matter that the Americans’ rifles were at low ready, not shoulder height.

Fear filled in the gaps.

The tears that spilled down the women’s faces in that hallway were not just about the present.

They were about everything the war had done to the word authority.

Later, in the barracks, when the search was over and each woman had been assigned a narrow bed with a thin mattress and a folded blanket at the foot, the story grew roots.

“They told us to face the wall,” Lotte said, sitting cross-legged on her bunk, blanket around her shoulders. “I thought—”

She broke off, laughter and leftover tears tangled in her throat.

“They had us lined up,” another woman—Ingrid—added, eyes still wide. “I heard the rifles. I swore they were lifting them.”

“They didn’t,” Gertrud said. “They were checking for knives, not shooting. We’re still here.”

She stretched out her stiff back, wincing.

“Doesn’t matter,” Ingrid muttered. “For a minute, they had our lives in their mouths and they chose three words we all know too well.”

Elisabeth lay back on her bunk and stared at the underside of the one above.

“What three words?” asked a soft voice from the end of the row, belonging to a girl who had been in the second group and had only heard the echoes.

“Elisabeth?” Lotte prompted.

“An die Wand,” Elisabeth said. “Face the wall.”

The girl’s face paled.

“They said that?” she whispered.

“Yes,” Elisabeth said. “And we cried. Some of us. Perhaps all, on the inside.”

She exhaled.

“And then they searched us and handed us tin cups with thin coffee,” she added, as if that erased the pattern.

It did not.

It complicated it.

Rumors, fed on snippets like this, did not want complications.

They wanted sharp edges.

Already, by nightfall, some women in the third barrack were telling it differently.

“They lined us up to shoot us,” one said. “But then the officer changed his mind.”

“They wanted to scare us,” another insisted. “To see us beg.”

“They must enjoy it,” a third concluded. “Saying the words and watching our faces.”

Elisabeth listened, leaning against the cold wall, her hands around a tin mug of lukewarm drink.

She thought of the sergeant’s eyes—tired, startled when he realized what his order had meant to them.

She thought of his clumsy German: No schießen. Kaffee. Soup.

“I don’t think they enjoy it,” she said quietly.

Three heads turned toward her.

“Then why did he say it that way?” Ingrid demanded.

“Because he says it to everyone,” Elisabeth replied. “We are not special. Not in the order, at least.”

It was not a comforting thought.

To be singled out for cruelty was one thing.

To be treated as just another line in a procedure manual was somehow more erasing.

“That doesn’t make it better,” Lotte muttered.

“No,” Elisabeth agreed. “It just makes it… different.”

The corridor incident might have remained a small, raw memory, shared only among a few women in one camp, if not for the fact that people, decades later, started asking questions.

Historians, journalists, curious grandchildren—all of them hungry for stories that made sense of the war in a way official communiqués never had.

One of those grandchildren, a young woman named Sabine, sat hunched over a tape recorder in the 1970s, across from her grandmother in a tidy German living room that smelled faintly of starch and stew.

“Tell me about the Americans,” Sabine said. “Were they… kind?”

Her grandmother, the same Gertrud who had told the others not to surrender their deaths before they were taken, snorted.

“‘Kind’ is not a word I use easily about men with weapons,” she said. “But they were not… monsters. Not like some I could name.”

She sipped her tea.

“Once,” she said, “they told us to face the wall.”

Sabine leaned forward.

“In a corridor,” Gertrud went on. “We thought they were going to shoot us. We all cried.”

Her gaze unfocused, tracking something invisible.

“They didn’t,” she added. “They searched us. They gave us soup.”

She shrugged.

“Hard to put that into one word, hm?” she said. “Kind. Cruel. Confusing. All at the same time.”

The tape recorder whirred softly.

Years later, when a historian named Hannah Greene listened to that tape in an archive, she paused it and rewound three times.

“Once… they told us to face the wall. We thought they were going to shoot us. We all cried.”

That line went into a footnote in her book.

The footnote became a paragraph in a later article.

The paragraph, pulled out of context, would eventually become a pull quote on a website, under a headline that promised more neatness than reality allowed:

“‘FACE THE WALL’: ONE ORDER THAT MADE GERMAN WOMEN POWs THINK THEY WOULD BE EXECUTED.”

The arguments started almost immediately.

In an online forum dedicated to World War II history, user PanzerBuff89 copied the quote and added his own commentary.

“Seems overblown,” he wrote. “Americans never executed female POWs like that. This is just German victim culture, trying to make themselves look like the real sufferers.”

Replies stacked up.

One, from ArchivistHannah, read:

“As the person who actually interviewed some of these women—or at least worked with their recorded testimonies—I can assure you they were describing fear, not claiming there was a secret American execution program. Fear can be real even when the threat is not.”

Another, from USVet42, added:

“Served in Korea. We used ‘face the wall’ to search POWs too. Nobody got shot. But if you’d been living in a regime where ‘face the wall’ meant something else, I can see why they’d panic.”

A third, from GranddaughterOfGertrud, wrote:

“My grandmother is the one in that tape. She always said the Americans could have handled it better. They didn’t have to use that phrase. But she also said: ‘They gave us soup after.’ She kept both truths together.”

The discussion became, in the way of all such threads, serious and tense.

Some users insisted intention was all that mattered.

“They weren’t going to shoot them,” one wrote. “So stop acting like it’s some moral failing.”

Others insisted impact was the real measure.

“If your ‘standard procedure’ triggers a trauma response in people you have total control over,” another argued, “maybe consider changing the procedure.”

Someone else tried to split the difference.

“Both things can be true,” they wrote. “That the Americans were following routine. And that the women had good reason, based on their previous experiences with uniforms and walls, to think routine could mean death.”

In a footnote to a later edition of her book, Hannah Greene summed it up more academically:

“The ‘Face the wall’ incident illustrates the chasm between the guards’ perception of a search as banal and the prisoners’ perception of the same action as potentially murderous. The moral question is less ‘Were the Americans in fact about to kill them?’ and more ‘How seriously did they consider, and respond to, the prisoners’ understandable terror?’”

That question did not lend itself to easy memes.

Which did not stop people from trying.

At a conference in London on “Ethics in Captivity,” a panel discussed the incident live.

On stage were Dr. Greene, a retired American colonel who’d served in Vietnam, and a much younger German scholar named Lukas Stein.

The moderator, a BBC journalist, read the quote aloud.

“Once,” she said, “they told us to face the wall. We thought they were going to shoot us. We all cried.”

“Dr. Greene,” she asked, “what do you think this tells us about the differences in how captors and captives experience the same event?”

Greene adjusted her glasses.

“The guards thought they were doing something protective,” she said. “Searching for contraband, reducing risk. The women experienced it as a near-execution because of the cultural weight of that phrase and their prior experiences with state violence.”

Stein leaned forward.

“I’d go further,” he said. “It shows that even when acting within legal bounds, captors can, through carelessness or lack of imagination, inflict psychological harm. It is not enough to say, ‘We did not shoot them, therefore we acted well.’”

The retired colonel frowned.

“With respect,” he said, “war is not a seminar in phrasing. You have procedures. You follow them. You can’t be polling prisoners on which orders make them anxious.”

Stein bristled.

“Surely we can expect a minimal level of empathy,” he said. “If you know your prisoners come from a background where ‘face the wall’ often precedes a gunshot, maybe pick different words.”

The colonel shrugged.

“Easier said than done when you’re twenty-one, tired, and trying to keep your men and your prisoners alive,” he replied. “The sergeant in that story didn’t have a handbook saying ‘Avoid triggering phrases.’ He had one saying ‘Search prisoners this way.’”

The moderator turned to Greene.

“Where do you fall in this?” she asked.

Greene sighed.

“Somewhere frustratingly in the middle,” she said. “Which, I know, makes nobody happy.”

The audience chuckled.

“I think the Americans in that hallway were not sadists,” she continued. “But they were also not saints. They could have noticed the tears sooner. They could have explained better. They eventually did, a little, when one of them realized what was happening. That matters.”

She glanced at the colonel.

“I also think we underestimate how hard it is, in the moment, for people immersed in one set of routine meanings to recognize another,” she said. “To them, ‘face the wall’ meant ‘stay still.’ To these women, it meant ‘prepare to die.’”

Stein opened his mouth, then closed it again.

“In an ideal world,” Greene concluded, “guards would be trained to understand the cultural histories of their prisoners, and adjust accordingly. In reality, we get clumsy, half-decent compromises like this one. No one dies. No one feels entirely safe, either.”

The moderator nodded.

“And the women?” she asked quietly. “What did it mean to them, in the long run?”

Greene thought of the tapes, of the shaky laughter that often followed the recollection.

“For some,” she said, “it was the day they realized the enemy who held their lives might not use them as callously as their own government had. For others, it was simply another day when someone else’s routine ran roughshod over their fears.”

She paused.

“Either way,” she added, “they cried.”

In a small apartment in Berlin, many years after that conference, an older woman sat at a kitchen table while her granddaughter recorded her for a school project.

The granddaughter’s assignment was simple: “Interview someone about a moment in their life when they were very afraid, and what happened next.”

Oma, the girl thought, had several to choose from.

“So,” the girl—Lena—asked, holding her phone carefully, “do you remember a time in the camp when you thought… everything was over?”

Her grandmother—Elisabeth, hair white now but eyes still as sharp as ever—tilted her head.

“Only one?” she asked.

Lena laughed nervously.

“Maybe one that stayed with you,” she said.

Elisabeth considered.

“There was the day of the river,” she said. “But that was another camp. Another story.”

She tapped her finger on the table.

“And there was the hallway,” she said. “With the wall.”

Lena leaned in.

“What happened?” she breathed.

“They told us to turn and face it,” Elisabeth said simply. “We thought they were going to shoot us.”

The words were as matter-of-fact as if she were describing rain.

Lena’s eyes widened.

“What did you do?” she whispered, even though she already knew, from the hint in the question, that the answer would not be “we were shot.”

“We cried,” Elisabeth said. “Some of us quietly. Some of us not.”

She remembered the taste of plaster dust, the smell of damp brick and nervous sweat.

“And then?” Lena prompted.

“They searched us,” Elisabeth said. “They found nothing. They gave us soup.”

She smiled faintly.

“Disappointing ending for you, hm?” she teased. “No dramatic escape, no last-minute reprieve from the gallows.”

Lena shook her head.

“No,” she said. “I think… the fact that you cried and then had to go do something as ordinary as drink soup is… I don’t know. Very… war.”

Elisabeth chuckled.

“Yes,” she said. “Very war.”

Lena frowned thoughtfully.

“I read online,” she said slowly, “that some people use your story to say the Americans were cruel. Others use it to say they were kind. It made me angry. Like they were tugging at you from both sides.”

Elisabeth’s eyebrows rose.

“You read discussions about this?” she asked. “Where?”

“On forums,” Lena admitted. “In the comments under articles. People saying, ‘See, they’re making it sound like Americans almost killed them’ or ‘See, they were traumatized by their own regime, not the Allies.’”

She wrinkled her nose.

“It feels like they’re arguing over you instead of listening,” she said.

Elisabeth patted her hand.

“They are arguing over themselves,” she said. “Over what they want to believe about the past. I am only a mirror they hold up.”

She took a deep breath.

“To me,” she said, “that day means three things. First, that fear does not care about intentions. Second, that procedures do not care about fear. And third…”

She smiled.

“…that a tired man with a bad accent can, if he chooses, realize what is happening and say, ‘No schießen. Soup.’”

Lena laughed, the image disarming something tight in her chest.

“If you could tell those people online one thing,” she asked, “what would it be?”

Elisabeth thought.

“Tell them,” she said slowly, “that they should be less interested in whether the Americans were perfect or the Germans were innocent, and more interested in what happens when you have power and someone else has their nose to the wall.”

She met her granddaughter’s eyes.

“And tell them,” she added, “that if they ever find themselves the ones giving orders, they should say more words and shout less. It won’t make anyone’s old nightmares go away. But it may give fewer new ones.”

Lena stopped the recording.

“Do you still… feel it?” she asked softly. “When someone says, ‘Face the wall’?”

“No,” Elisabeth said. “When you paint your kitchen, you say it cheerfully. ‘Turn, face the wall, hold the brush.’ Words can be tamed again.”

She hesitated.

“But sometimes,” she admitted, “if I am in a narrow hallway and someone closes the door behind me, my heart remembers before my head does.”

She smiled, not sadly.

“It is allowed,” she said. “It beats. That is what matters.”

The hallway, the wall, the tears—they never made it into any official Allied communiqués.

They were not part of the grand narratives of battles or treaties.

They lived in the smaller places: in faded notebooks, in shaky interviews, in the spaces where people tried, years later, to explain moments when the war narrowed down to a few words and a few breaths.

“Face the wall…”

To the sergeant, it was procedure.

To the women, it was a possible last line.

To the historians, it became a case study in how routine and trauma collide.

To the anonymous strangers online, it became ammunition in arguments that had as much to do with contemporary politics as with the past.

To Elisabeth, to Lotte, to Gertrud, it remained something else.

A sharp, frightening breath inside a long, ragged exhale.

A place where they had already said goodbye, silently, and then had to learn, awkwardly and imperfectly, to keep living after.

They had cried.

They had flinched at the sound of English behind them.

They had turned, eventually, to face their captors as human beings rather than faceless executors.

The war, for them, was not redeemed in that corridor.

But something small shifted.

Enough that, years later, when someone asked if the Americans were kind, cruel, or something in between, they could say, with infuriating honesty:

“They told us to face the wall. We thought they would kill us. They did not. They searched us and gave us soup. You decide the word. I am done deciding for you.”

THE END

News

How a Fortress Prison Built to Silence “Enemies of the Reich” Accidentally Became a Secret University of Freedom, where Socialists, Catholics, and Conservatives Fought Over What Democracy Should Mean—and Carried Those Serious, Tense Arguments into the New Europe

How a Fortress Prison Built to Silence “Enemies of the Reich” Accidentally Became a Secret University of Freedom, where Socialists,…

How a Devoted Nazi Military Engineer Built War Roads Across Europe, Then Lived Long Enough to Watch Those Same Highways Become the Skeleton of a Peaceful Union He Never Imagined

How a Devoted Nazi Military Engineer Built War Roads Across Europe, Then Lived Long Enough to Watch Those Same Highways…

How a Devoted Nazi Army Surgeon Entered an American POW Hospital Expecting Revenge, Discovered a Forbidden Ledger of Compassion, and Sparked a Fierce Moral Battle That Outlived Barbed Wire and Surrender

How a Devoted Nazi Army Surgeon Entered an American POW Hospital Expecting Revenge, Discovered a Forbidden Ledger of Compassion, and…

How Japanese Women POWs Once Screamed “They’re Going to Drown Us!” When American Trucks Rolled Toward a Flooded River, and How That Terrifying Ride Turned Into Decades of Argument About Rumors, Mercy, and What We Choose to Remember

How Japanese Women POWs Once Screamed “They’re Going to Drown Us!” When American Trucks Rolled Toward a Flooded River, and…

How German Women POWs Whispered “They’ll Leave Us to Freeze” in a Whiteout Blizzard, Until American Guards Slung Them on Their Backs and Forced Everyone to Live Through a Night No One Could Forget

How German Women POWs Whispered “They’ll Leave Us to Freeze” in a Whiteout Blizzard, Until American Guards Slung Them on…

Why One German POW Woman Whispered “Please… Don’t Touch Me” During a Routine Exam, and How That Moment Forced American Doctors to Confront Trauma, Trust, and Their Own Assumptions

Why One German POW Woman Whispered “Please… Don’t Touch Me” During a Routine Exam, and How That Moment Forced American…

End of content

No more pages to load