How an Invisible Change Inside the “Doomed” Sherman Tank Turned It from a Burning Coffin into a Battlefield Survivor and Left German Commanders in 1944 Completely Confused by Ammunition That Suddenly Refused to Explode

By the spring of 1944, Sergeant Joe Tanner had heard every nickname anyone could invent for the M4 Sherman.

Most of them weren’t kind.

“Ronson,” the British called it, after the lighter that “lights every time.” Some Americans called it “Zippo,” for the same reason. A few of the grimmer voices in his unit simply said “the coffin,” and left the rest unsaid.

Joe didn’t need nicknames to know what people meant. He had seen a Sherman “brew up” once in Italy in 1943, and that memory was enough.

It had been a clear afternoon, too bright for the sort of thing that happened in the next few minutes. His platoon had rolled along a sun-blasted road lined with gray stone walls, vineyards stretching on either side. The air had smelled of dust and crushed olives. It might almost have been peaceful.

Until the first shot.

Joe’s tank, Lucky Lady, was second in line. The lead tank crested a small rise in the road, its engine roaring as the driver shifted gears. For just a moment, the hull was silhouetted against the sky.

There was a flash on the slope opposite—just a sparkle at first, like sunlight on glass. Then a sharp, flat crack, followed by a thunderclap that seemed to punch the air apart.

The lead Sherman jerked. Its turret rocked as if someone had kicked it. Then, as Joe stared from his periscope, a tongue of orange flame shot out of the commander’s hatch, followed by a thicker, darker blast from the side hull.

“Hit! They got them—!” someone shouted over the radio.

A second later, the tank turned into a lantern.

Fire poured from every opening—hatches, pistol ports, the barrel. The paint blistered. The long antenna curled like a strand of hair in a candle. Black smoke rose in a thick, ugly column.

Joe remembered the voice of the loader from that tank, a kid from Nebraska who’d traded stories about cornfields in the evenings.

He never heard that voice again.

Their platoon commander shouted orders, the driver backed them off the road, smoke rounds went out—everything became noise and movement and muddled impressions. Later, when the firing stopped and the landscape settled into a tense quiet, they returned to the charred hulks.

The lead Sherman was still smoldering, metal warped and split. Its turret lay at a crooked angle, half off its ring, as if it had tried to leap away and failed.

The ammo racks inside, someone said, had gone up in a chain reaction. One round cooked off, then the next, then the next. A line of invisible explosions ripped through the tank’s belly, turning it into a furnace.

That night, in a muddy bivouac, Joe sat alone beside the track of his tank, cleaning his carbine. The smell of burned oil still clung to his clothes.

He looked at the side of his own hull, where the 75mm rounds were stacked in dry metal racks just above the tracks.

So close to where he sat.

So close to where his crew slept.

“Hey, Sarge,” his gunner, Lewis, had said, trying for a cheer he didn’t feel. “You ever notice they put us right on top of the fireworks?”

Joe had looked at the pale line of Lewis’s face in the dark and, for once, had no answer.

Almost a year later, on another continent, Oberleutnant Dieter Hoffmann sat in an operations room and tried to make sense of a different sort of fire.

The room was deep inside a concrete complex outside Paris, safe from anything but the heaviest bombs. Maps covered the walls, lines drawn and redrawn in blue and red pencil. The air smelled of stale coffee, smoke, and tension.

On the table in front of him lay a stack of reports.

“PANZERJÄGER ABT. 521, SECTOR NORTH,” read one, stamped and initialed. Another bore the markings of an infantry division that had recently been forced back from a hedgerow line north of Saint-Lô.

Dieter rubbed his eyes and picked up the top sheet again.

“American medium tanks continue to appear in great numbers,” the report read in cramped German script. “Our anti-tank guns achieve hits at known weak points on hull side and front. However, in several cases, the enemy vehicle does not immediately burn. Crews escape more often than previously observed.”

He flipped to the next page.

Another report. Another variation of the same message.

“Three Shermans knocked out near Hill 112. Penetrations achieved. Only one caught fire.”

He leaned back.

It didn’t make sense.

He’d spent his early years in the war attached to an armored battalion in North Africa. There, under the harsh desert sky, he’d watched burning Shermans mark the horizon like morbid signposts. The British had joked bitterly about how easily the vehicles went up. German tankers, in their turn, had come to count on the sight—hit them right, and they burned.

Now, in Normandy, something had changed.

He stood and strode to the large map pinned to the nearest wall. Colored pins marked units, both theirs and the enemy’s. A line of small red flags indicated known American tank units.

“Shermans,” Dieter muttered, tapping one with his finger. “Always Shermans.”

A colonel across the room glanced up.

“Something bothering you, Hoffmann?” he asked.

“Several things, Herr Oberst,” Dieter replied. “But at the moment, these.”

He waved the reports.

“Ah yes,” the colonel said. “The ‘stubborn’ Shermans. I saw those summaries. Congratulations; the Americans finally learned how not to pack kindling into their tanks.”

The colonel’s tone was dry, but there was an undercurrent of worry.

“If we used the same tank for four years, we would have learned something too,” he added. “Do we know what they changed?”

“Not yet,” Dieter admitted. “We see less fire, more disabled but not destroyed vehicles. Some of our gunners say the armor must be thicker now. Others think they’ve changed their propellant. Or that they carry fewer shells. Nothing firm.”

“And intelligence from higher?” the colonel asked.

Dieter gave a humorless smile.

“Higher is busy moving arrows on this map,” he said. “They have not shared any secrets about enemy tanks lately.”

The colonel snorted.

“Find me something useful, then,” he said. “If the enemy’s medium tank no longer explodes like a festival rocket every time we look at it, I want to know why.”

Dieter nodded.

“That is what I am trying to do,” he said.

He returned to the table and picked up one more report. This one was different.

It included a sketch.

“Captured American tank, designated M4A3, examined near Caen,” it said. “Hull penetrated twice on right side by 7.5cm PAK. Fire damage minimal. Ammunition observed stored low in hull in boxes partially surrounded by what appears to be fluid containers.”

The sketch was simple but suggestive: a cutaway of the Sherman’s hull, showing the turret, the engine in the rear, and, along the floor, rectangular shapes labeled “ammo racks,” encased by shaded areas labeled only with a question mark.

Dieter tapped the page.

“Fluid,” he murmured. “Low storage. That’s…interesting.”

He reached for a cigarette, thought of the smoke already in the room, and put the packet away.

“Very interesting,” he said.

Joe rolled off the landing craft ramp into France on a gray June morning and tried not to think about Italian roads and burning tanks.

His new Sherman, painted with the name Second Chance in white letters on the hull, splashed through the shallow surf and tracked onto the sand. Ahead, low dunes and hedgerows loomed. Behind, the sea churned, full of boats and ships and more boats, all vomiting men and machines onto the beach.

“Keep her straight, Donny,” Joe called down to his driver through the intercom. “Last thing we need is to dig ourselves in on the first day.”

“Straight as an arrow, Sarge,” Donny replied, his voice tight. “Don’t worry. I’m more afraid of getting stuck than of the Germans.”

“That makes two of us,” Lewis, the gunner, chimed in.

They climbed up off the beach and into the chaos beyond—supply dumps, command posts, makeshift medical stations. The air buzzed with aircraft, shouted orders, the clatter of tracks.

Later, in a temporary assembly area, they parked in a long line with dozens of other Shermans. Men moved between the tanks, checking tracks, tightening bolts, cleaning guns.

Joe stood on the hull, hands on his hips, and looked down into the turret.

It was different from his old Lucky Lady, in ways both obvious and subtle.

For one, the ammunition racks that used to line the sides of the hull were gone.

Instead, there were rectangular steel bins built into the floor, under the turret basket—heavy, squat things with thick lids.

“What do you think, Sarge?” Lewis asked, popping his head out of the gunner’s hatch.

“I think someone finally thought about where they put the explosives,” Joe said.

He climbed down into the turret and tapped one of the floor bins with his boot.

“Open her up,” he told the loader, Corporal Eddie Morris, who sat nearby wiping lubricant off a shell.

Eddie grunted and lifted the lid of the bin.

Inside, 75mm rounds gleamed in neat rows. Around them, lining the thin space between the box and the hull, were metal jackets, welded and sealed.

“What’s with the jackets?” Lewis asked. “They look like they’re meant to hold something.”

“Water,” said a voice from the turret hatch.

A captain in ordnance corps insignia leaned down, one hand braced on the rim.

“Who are you, Sergeant?” he asked.

“Joe Tanner, sir,” Joe said. “Third platoon, Company B.”

“Well, Tanner, what you’ve got there is the new ‘wet stowage’ system,” the captain said. “Started rolling out late last year. The boxes hold your ammo. The jackets around them hold a fluid mix—mostly water, a little rust inhibitor.”

“Wet…stowage?” Eddie repeated, skeptical. “We’re putting water around shells now? You sure we’re not supposed to be floating this thing across the Channel?”

The captain chuckled.

“Trust me, Corporal, you floated just fine this morning,” he said. “No, the idea is simple. The old dry racks—you’ve seen what happens when they get hit.”

Joe’s jaw tightened.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“We all have,” the captain said, nodding. “Rounds stacked along the hull walls, powder bags exposed. Armor’s pierced, flame gets in, and the whole load goes off like a string of firecrackers. That’s where the ‘Ronson’ nicknames came from.”

He rapped the floor box with his knuckles.

“This setup is meant to change that,” he went on. “By moving the ammo down into the hull, below the sponsons, and surrounding it with water jackets, you get two benefits. First, harder target to hit. Second, if the armor’s pierced and hot fragments get in, that fluid helps smother any burn before the propellant cooks off.”

Lewis whistled.

“So if we get hit,” he said, “we don’t turn into a lantern?”

“That’s the idea,” the captain said. “You can still be knocked out—mobility kill, gun out, crew injured. This isn’t magic. But the odds of this tank turning into a funeral pyre are a lot lower.”

He straightened, his boots clanging on the hull as he stepped back.

“Just remember,” he added, “it works best when you store your rounds in the floor bins and not in every empty corner of the tank. I know you boys like to bring ‘extras’ to feel better, but if I find shells tucked into wall racks, I’ll have your hides.”

Eddie nodded vigorously.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

When the captain moved on, Lewis leaned closer to Joe.

“What do you think?” he asked. “You buy it?”

Joe looked down at the floor bins, then up at the open sky.

“I buy that a little water’s better than none,” he said. “And I know I’d rather sit on top of ammunition that’s trying hard not to explode than on top of piles waiting to get excited.”

He glanced at the scorched patch of paint on his old helmet, a faint reminder of heat that had licked too close in Italy.

“Besides,” he added, half to himself, “if it gives us even one more second to get out if we’re hit, that’s worth all the water on this side of the Channel.”

In late July, near a small Norman village whose name Joe never remembered properly, Second Chance found out whether the name was more than paint.

The hedgerows felt like a maze built by someone who hated tanks.

Thick, tangled walls of earth and roots, taller than a man and sometimes almost as tall as the tank, lined narrow lanes. Every opening could hide a gun. Every orchard could conceal a panzer.

“Feels like driving down a hallway with doors on both sides and no idea who’s behind them,” Donny muttered over the intercom.

“Right now, I’m more worried about what’s in front,” Lewis replied, squinting through his sight.

Their platoon moved at a cautious crawl. Infantry slogged along in ditches, eyes scanning the hedges.

Suddenly, the radio crackled with a burst of urgent German.

“PANZER LINKS! PANZER LINKS!”

“That’s not ours,” Eddie said. “They’re shouting to each other.”

Joe swung his binoculars toward the left, where a gap in the hedgerow opened into a small field.

For a fraction of a second, he saw it.

A low, dark shape. Sloping armor. A cross painted on the side.

Then a flash from its muzzle.

There was no time to think, only to shout.

“Down! Brace!”

The world slammed sideways.

Joe heard a tearing metallic shriek, like someone ripping the hull with a giant can opener. The interior of the tank rang. Something heavy clanged. Eddie cursed; Lewis yelled; Donny swore he’d been punched in the chest.

Lights flickered. Dust and paint flakes rained down. The smell of hot metal flooded the compartment.

For a heartbeat, Joe waited for the rest.

The flash.

The roaring fire.

The heat punching up from below.

It didn’t come.

“Report!” he barked, voice higher than he intended. “Everybody alive?”

“My ears are ringing, but I’m here,” Lewis gasped. “Gun’s still on. Sight’s cracked, but I can see.”

“Driver okay,” Donny said. “Feels like someone kicked the front plate, but no new holes in me.”

“Loader,” Eddie wheezed. “Still ugly. Still present.”

Joe forced himself to breathe.

The tank was still moving, though sluggishly.

“Donny, back us out,” he ordered. “Smoke, now!”

Outside, someone fired smoke rounds. White clouds blossomed across the gap.

They reversed into cover, crunching through branches. Another shot from the panzer cut through where they’d been seconds before, plowing soil.

Inside, Joe clambered down to inspect the damage.

The right side of the hull, just above the track, bore a jagged inward bulge. The shot had penetrated, but not cleanly. Shards of steel had sprayed into the interior like shrapnel.

One chunk of glowing metal lay on the floor near the ammo bin, cooling.

There was a scorch mark on the side of the box.

But the lid remained intact.

He touched it cautiously.

Warm, but not blazing.

Inside, the shells sat in their rack, undisturbed.

“Mother of—” Eddie began, then stopped himself. “It hit the bin, didn’t it?”

“Looks like it glanced off the armor and spent itself,” Joe said, examining the path. “If this were the old setup…”

He didn’t finish.

He didn’t have to.

They all knew how the story would have ended in Italy.

“Guess we baptized the wet stowage,” Lewis said weakly.

“That panzer still out there,” Donny reminded them.

They got back into the fight, calling in artillery, helping direct fire on the panzer’s suspected position. Eventually, the enemy tank moved or burned or simply vanished into the hedgerows; in the confusion of battle, it was hard to be sure.

Later, when things calmed enough for a maintenance crew to crawl over Second Chance, an ordnance officer shook his head in grudging respect.

“Another few centimeters and that round would’ve gone straight in,” he said, tapping the dented hull. “As it is, the angle saved you. And so did that water. We drained the jackets—got steam, some boiling, but no cooked ammunition. You boys are lucky.”

“Lucky,” Donny said. “Right. That’s what they called our last tank, Sarge. I like ‘Second Chance’ better.”

Joe sat on the hull as the sun went down, the metal warm under him, and watched the sky turn pink over the Norman countryside.

He thought of the Italian road, the black column of smoke, the silence afterward.

He thought of the hiss of water inside the armor next to him, doing its quiet work.

For the first time in a long while, he let himself believe that someone, somewhere, had learned from what they’d seen and decided to do better.

Dieter Hoffmann peered into the gutted hull of the knocked-out Sherman and tried to imagine the last seconds of the crew’s day.

The tank sat in a hedgerow lane now silent except for distant artillery echoes. Its tracks were half buried in dirt, the rubber on the road wheels scorched. A jagged hole gaped in the side, smelling of burned paint and oil.

But the interior was strangely…orderly.

A crater on the far field, blackened around the edges, marked where an anti-tank gun position had fired and been destroyed in return. The Sherman had taken at least two hits. One had punched through the right side; another had gouged the front glacis.

Yet there was no familiar evidence of a catastrophic ammunition detonation. The turret hadn’t blown off. The hull roof hadn’t peeled back. The interior was charred, yes, but not gutted.

A few streaks of dried soot marked the hatches where the crew had obviously bailed out—whether they reached safety, Dieter didn’t know. The bodies had been removed already.

He ducked into the hull, boots scraping on steel.

“Careful, Herr Oberleutnant,” called the corporal outside. “We checked for booby traps, but…”

“If the Americans start wiring their wrecks with traps, we’ll have other problems,” Dieter replied.

He crouched by the floor.

There they were again.

Ammo bins. Low, rectangular, with thick lids. Around their sides, metal jackets, some cracked by the blast. When he tapped one, his knuckles met a hollow, sloshing sound.

“Water,” he murmured.

He gestured to the corporal.

“Bring that canteen,” he said.

The corporal passed it in. Dieter unscrewed the cap, dipped a finger in the liquid pooled under a damaged jacket, and tasted it cautiously.

Faintly metallic, but otherwise just water.

He climbed back out into the sunlight.

“It’s a clever system,” he said. “Very simple.”

The corporal frowned.

“What is, sir?” he asked.

“Their answer to our jokes,” Dieter said.

He straightened and wiped his hands on his trousers.

“Tell the others to make note,” he added. “If they still think every Sherman will burst into flames as soon as they touch it, they’re fighting last year’s tank.”

Later, in his report, he wrote:

“New M4 variants appear to store ammunition in floor-level containers, some surrounded by liquid compartments. Likely intended to reduce incidence of fire following penetration. Evidence from several wrecks supports this. Recommend adjustment of training: emphasize that enemy crews may survive initial hits more often; follow-up fire necessary.”

The report went up, along with a hundred others, into the hierarchy’s paper mountain.

Somewhere, perhaps, someone read it and added it to their understanding.

But the war had become a river in flood. No one alteration, however clever, could turn it aside.

For Dieter, the observation lodged in his thoughts for different reasons.

He had spent years watching each side react to the other, adjustment after adjustment. Thicker armor. Better guns. Different tactics.

This small change struck him as something else.

It was not meant to kill more effectively.

It was meant, primarily, to save the men inside.

As an officer whose job was now to parse the enemy’s mind as much as their equipment, he found that significant.

“Even their engineers are thinking about their crews,” he wrote in a private notebook he kept for his own reflections, separate from official reports. “In our designs, we think often of performance, sometimes of protection. For them, protection is becoming a performance metric, not a luxury. It shapes their machines.”

He paused, then added one more line.

“Perhaps that is what happens when one expects to be able to bring men home.”

The war ended, as wars do, with a mixture of noise and silence.

In the summer of 1945, Joe stood on the deck of a troopship and watched New York grow on the horizon—tall, glittering, improbable. The harbor was filled with ships, tugs chugging between them like purposeful beetles. Bands played on some decks. Men cheered, shouted, or simply stood and stared.

Second Chance was somewhere in Europe still, turned over to other units or scrapped or parked in a depot. Joe didn’t know. The tank had carried him across France, into Belgium, over the border into Germany. It had been hit again once, glancing blows and near misses. The wet stowage had never had to prove itself quite as dramatically as that first day in Normandy.

But he never forgot that first slow, terrified breath after realizing they were still alive.

Back home in Ohio, he worked in a factory for a while, then got a job driving trucks. He married. Had a son. Built a small life.

The nightmares came and went. Sometimes they were of burning tanks. Sometimes of hedgerows. Sometimes of nothing he could name.

When his son, Michael, was twelve, he brought home a library book about World War II tanks.

“Dad, look,” Michael said, flipping the book open on the kitchen table. “They talk about your tank. The Sherman.”

Joe glanced at the pictures.

There it was—a gray-green Sherman on a move, soldiers on its hull, captioned with details about armor thickness, gun calibers, production numbers.

The text mentioned “wet ammunition stowage,” noting that “later models showed a marked improvement in crew survivability when hit.”

“That was you, right?” Michael asked. “You had the better kind?”

Joe nodded, chasing a crumb of bread on his plate with his fork.

“Yeah,” he said. “We did. Eventually.”

Michael frowned.

“It says here the early ones burned a lot,” he went on. “Did you see that?”

Joe’s hand tightened on the fork.

“Yes,” he said quietly. “I saw that.”

He considered how much to say.

How much a twelve-year-old needed to know.

“Is it true the Germans called them ‘Tommy cookers’?” Michael asked, reading.

Joe chuckled without humor.

“Some did,” he said. “We had our own names for their tanks, too. Nobody comes out of a fight without calling the other fellow something.”

He tapped the page where the words “wet stowage” appeared.

“You see that?” he said. “That little change? Someone, somewhere, looked at all the wrecks and all the burned crews and said, ‘We can do better.’ So they moved the ammo and wrapped it in water and metal. Didn’t make the war good. Didn’t make us invincible. But it meant more men climbed out instead of…not.”

Michael listened, eyes wide.

“You think it saved you?” he asked.

Joe thought of the glowing shard of steel on the ammo bin floor, the unbroken lid, the feel of his crew’s voices still answering him after the hit.

“Yes,” he said simply. “I do.”

Michael traced the picture with one finger.

“That’s kind of amazing,” he said. “A few inches down, some water, and suddenly a bad tank is…less bad.”

“Sometimes that’s all you get,” Joe said. “Less bad.”

He ruffled his son’s hair.

“And sometimes ‘less bad’ is the difference between you sitting here and me explaining this to someone else’s kid,” he added.

In 1969, in a museum in England that smelled of oil, dust, and polished brass, two men stood side by side in front of a Sherman tank and read the same plaque.

“‘M4A3 Sherman, late-war production,’” the sign said. “‘Equipped with wet ammunition stowage. This modification, introduced in 1944, significantly reduced the tendency of the tank to catch fire when penetrated.’”

Joe, now with more gray in his hair than brown, shifted his weight from one foot to the other and smiled faintly.

“Wet stowage,” he murmured. “There’s that phrase again.”

“At least they mention it,” said the man next to him in accented but clear English. “The early ones…we knew them by the smoke.”

Joe turned.

The man was in his late forties or early fifties, dressed in a plain jacket and slacks. His hair was thinning. On his lapel, a small pin in the shape of a tank sat next to one shaped like a cross.

His nametag, given out by the museum for a veterans’ gathering that day, said “D. Hoffmann.”

“You were on the other side?” Joe asked.

The man nodded.

“Panzer officer,” he said. “Once. Later, intelligence. Now, just a man with grandchildren who like stories about machines.”

Joe chuckled.

“Same here,” he said. “Well, replace ‘Panzer’ with ‘Sherman.’”

Hoffmann’s eyebrows rose.

“Ah,” he said. “So you rode these.”

“Rode them, cursed them, patted them when they behaved,” Joe said. “And in the end, I think I owe this particular version my life.”

He gestured toward the hull.

Hoffmann tilting his head.

“In Normandy?” he guessed.

“How’d you know?” Joe asked.

“In 1944,” Hoffmann said, “we started getting reports. Our gunners said, ‘We hit the Sherman, it stops, but it does not always burn.’ Before that, they burned more.”

He gave a small shrug.

“I came to examine some of the wrecks,” he went on. “We found the ammo in the floor, little tanks of water around them. We wrote reports. I doubt anyone noticed in the chaos. But I noticed.”

He pointed to the plaque.

“It is…strange,” he said. “To see it here now, a small line in a museum. At the time, it felt like…how do you say…someone had quietly changed the rules.”

Joe nodded slowly.

“For us, too,” he said. “The first time we took a hit and didn’t go up—” He stopped, eyes unfocusing for a moment, then shook his head. “I remember thinking, ‘The tank is still a target, the enemy’s still out there, but somebody cared enough to put water where it counts.’”

Hoffmann smiled faintly.

“You know,” he said, “when I talk to young people now, they ask about big things. Famous battles. Famous commanders. They want to hear about slogans, and medals, and who was ‘right.’”

He tapped the side of the Sherman, knuckles ringing on steel.

“I tell them about this instead,” he said. “About engineers and workers who changed a drawing so that more men came home. About how, even in a war, someone can make a decision that leans toward life, not only toward destruction.”

Joe looked at the tank, at the innocuous words on the plaque: “wet stowage,” “crew survivability.”

He thought of the kid from Nebraska, gone in a burst of fire on an Italian road, and of the four men who had shared Second Chance with him and gone home.

“All those big strategies,” he said quietly, “and one of the things that stuck, for me, is a tank with water in its belly.”

Hoffmann nodded.

“Sometimes the ‘deadly secret,’” he said, echoing the museum’s promotional brochure he’d seen at the entrance, “is not a new gun or armor. It is the realization that dead crews do not win wars.”

They stood in silence for a moment, two former enemies sharing the weight of the same memory from different angles.

Behind them, a group of schoolchildren shuffled past, their guide explaining the basics of armor and tracks in a bright voice. One boy glanced up at the tank, eyes wide, then ran to catch up with his friends.

“He will read the sign one day,” Hoffmann said. “Maybe he will think, ‘Interesting.’ Maybe he will not think at all. But the fact that this story is on metal instead of only in our heads—that matters.”

Joe smiled.

“Yeah,” he said. “It does.”

He extended his hand.

“Sergeant Joe Tanner,” he said. “United States Army. Once upon a time.”

Hoffmann took it.

“Oberleutnant Dieter Hoffmann,” he said. “German Army. Also once upon a time.”

Their grip was firm, brief, and very real.

As they let go, Joe glanced once more at the Sherman’s hull, at the invisible space inside where water had once surrounded boxes of shells.

No one building the tank had known his name.

They hadn’t known who would sit on the seats above those boxes, who would shout into those headsets, who would flinch when the first hit came.

They had only known that there was a problem, and that they could make it less terrible.

That decision had traveled across oceans and years, through factories and front lines, all the way to a hedgerow in France and a handshake in a museum.

From the outside, it looked like nothing.

From the inside, it had been everything.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

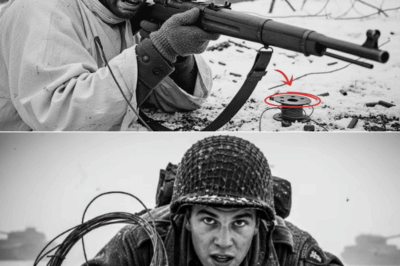

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load