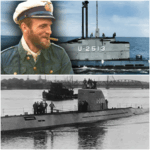

How a Sleep-Deprived Submarine Mechanic Turned a Scrap of Canvas and Spare Bolts into a Pressure-Saving Patch That Stopped a 300-Foot Leak and Gave Seventy-Eight Sailors One More Sunrise

At three hundred feet down, the ocean didn’t roar.

It whispered.

The pressure squealed along the seams of the hull in a constant, high, complaining note, like distant brakes that never quite stopped. The lights hummed. Somewhere aft, the big electric motors thrummed with steady, stubborn power.

Chief Motor Machinist’s Mate Leo Ramirez knew every one of those sounds.

They were his lullaby.

And his alarm.

He was standing in the narrow passage outside the aft battery compartment when he heard a new one: a sharp, hollow ping that didn’t belong, followed by a muffled, metallic crack.

He froze.

On a submarine, a new sound wasn’t curiosity.

It was a question with only bad answers.

“Did you hear that?” someone whispered in the gloom.

Before anyone could reply, the whole world jumped.

The depth charge didn’t hit the hull directly. It went off somewhere above and aft, a dull, heavy slam that shoved the submarine sideways and then back, as if a giant hand had swatted her. The lights flickered. Dust sifted from the overhead.

The constant high squeal of the hull rose half a note.

The USS Hawthorn groaned.

Then came the hiss.

Not air. Air leaks had a dry, whistling sound.

This was wetter. Colder.

Leo’s heart clenched.

“Flooding!” someone shouted from the aft end. “We’ve got a leak—!”

The rest of the sentence vanished under the shriek of the collision alarm.

Leo ran.

His boots hit the steel deck with the same steady rhythm as the electric motors, but his mind was racing ahead, mapping the aft section automatically. Motor room. Shaft alley. After trim tank. Auxiliary machinery space.

“Seal that compartment!” the diving officer’s voice snapped over the intercom, crackling with urgency. “Find that leak and report!”

Men pressed against the bulkheads to let Leo pass.

He was not the biggest man on the boat—five-eight on a good day, wiry from years of wrestling stubborn metal—but the crew moved for him like water around a rock.

Chief Ramirez meant you were either about to get yelled at or about to get saved.

Sometimes both.

He pushed through the oval hatch into the engine room and blinked against the sudden change in light. The overhead bulbs here were brighter, reflecting off pipes and gauges and the massive, silent shapes of the diesel engines that slept while the boat ran on batteries.

Now, one end of the engine room was a misty haze.

Water sprayed from somewhere low along the port side, a solid, glittering stream that splashed against the frame of one of the old diesels and ran across the deck in a growing sheet. Two sailors were already on their knees, trying to stuff rags into the flow. The rags fluttered away like paper.

“Out of the way!” Leo barked.

They scrambled aside.

He dropped into a crouch, icy water soaking his knees, and peered along the line of the hull. The spray was coming from a jagged hairline crack in a weld seam near the base of a frame. It wasn’t big—no wider than his thumbnail—but at three hundred feet, “small” was a cruel joke.

Every square inch of the hull was taking tons of pressure. The crack was a pinhole between that weight and the air inside.

The ship’s skin was bleeding.

“How bad?” Lieutenant Connors shouted from the hatchway, clutching the frame to steady himself.

Leo wiped water from his eyes.

“Steel’s cracked along the seam,” he shouted back. “We take a few more jolts, it’s going to open up like a zipper.”

As if on cue, a second depth charge went off in the distance.

The hull rang like a bell. The stream of water twitched, thickened, and the crack spat a spray that hit Leo full in the chest.

He gasped at the shock of the cold.

“All hands, this is the captain,” a calm, firm voice came over the intercom. “We are at three hundred feet and holding. We have a leak aft. Damage control is in progress. Stay at your stations and stay calm.”

Leo almost laughed.

Stay calm.

Sure.

The deck vibrated under his knees as the Hawthorn adjusted trim, shifting water in her tanks to compensate for the flooding.

A young seaman beside him whispered, “Can we hold at this depth, Chief?”

Leo’s brain flipped to numbers like cards in a file.

Three hundred feet.

Nominal test depth: about that.

Crush depth: deeper. But not deeper enough to feel safe.

“How much water in the bilge?” he snapped.

“Coming up fast,” the seaman said. “We’re pumping, but…”

He trailed off.

At this rate, the pumps could buy time.

But time for what?

You couldn’t weld steel under that kind of spray. You couldn’t slap a normal patch over a crack that wanted to become a tear.

You’re a mechanic, Leo told himself. Not a philosopher.

Fix it.

He looked around the engine room like a man looking through a toolbox of gods and jokes: pipes, valves, spare gaskets, lengths of chain, a half-disassembled water pump, a scuffed toolbox that had followed him from boat to boat.

And, hanging on the bulkhead near the ladder, a rolled canvas tarp, stained and patched, used a hundred times for everything from wrapping machinery to dividing a compartment.

Canvas.

An idea flickered.

It was ridiculous.

But ridiculous ideas had been getting sailors home since the first idiot floated across deep water on a log.

“Cortez!” Leo shouted.

The young seaman jumped.

“Yeah, Chief?”

“Grab that canvas. The big tarp. And my spare bolt box. Move!”

Cortez scrambled for the ladder.

Lieutenant Connors frowned.

“Chief, what are you thinking?” he asked.

Leo grinned humorlessly.

“I’m thinking I’m about to build the ugliest bandage this boat has ever seen,” he said. “But it just might hold long enough to get us up a few dozen feet.”

“Is that enough?” Connors asked.

Leo shrugged.

“I’ll let you know when I can breathe again,” he said.

He had done this before.

Not exactly this—no one practiced “makeshift hull patch at three hundred feet” in peacetime—but things like it.

On his first boat, a valve in the high-pressure air system had failed during a test dive, turning a gasket into confetti and putting a fog of icy vapor into the compartment. Leo had grabbed a scrap of leather, cut a circle, and bolted it into place with all the gentle care of a dockside brawl.

On another, a fuel line had developed a hairline crack halfway through a patrol. They hadn’t had the right replacement. He’d built a sleeve out of metal scavenged from a storage rack, wrapped the line, and clamped it down so tight it squeaked.

He believed in proper parts, proper tools.

He also believed in not dying while waiting for them.

Cortez slid down the ladder, canvas bundle on one shoulder, metal box banging against his hip.

“Here, Chief,” he panted.

Leo unrolled the tarp. It was big, enough to cover a jeep, thick enough to have some substance.

“Cut me a square,” he said. “About a foot on a side. Double layer.”

Cortez hesitated.

“With what?” he asked.

Leo jerked his chin at a nearby workbench.

“My snips are in the top drawer,” he said. “Try not to cut your fingers off. We’ve already got one leak; don’t need another.”

As Cortez went to work, Leo pried open the bolt box.

He’d been accused, more than once, of hoarding hardware like a squirrel. Old bolts, washers, metal strips that other men would have tossed—he kept them all, sorted and labeled in his neat, spidery handwriting.

You never knew.

Now he dug for the biggest, flattest washers he had, the ones the suppliers sent by mistake.

“Chief?” Connors said, fighting to keep his voice level. “Talk to me.”

“The hull’s not going to magically heal itself,” Leo said. “But we might be able to spread the load. Canvas on the inside, held tight to the crack with bolts and backing plates. It won’t stop the water completely, but it can slow it. Keep the crack from growing.”

Connors glanced at the stream of water. It had thickened again, spraying higher, splashing against the diesel block.

“Will bolts hold in that steel?” he asked.

Leo swallowed.

“Not bolts,” he admitted. “Studs. We’ll have to drill. Fast.”

“Drill,” Connors repeated faintly. “Into the hull. At three hundred feet.”

Leo met his eyes.

“We drill holes where the steel’s still solid,” he said. “We put in threaded studs. We clamp the canvas between big washers and backing plates. We turn one screaming crack into a series of very annoyed drips.”

“And if the drilling makes it worse?” Connors asked.

“Then we go quicker,” Leo said. “And you tell the captain we tried.”

The lieutenant stared at him for a long second.

Then he nodded.

“Do it,” he said. “Whatever you need, you’ve got it.”

The first time Leo had ever drilled into a hull plate, he’d been twenty years old and terrified.

Back then, an old chief had stood over his shoulder, barking corrections.

“Listen to the bit,” the man had said. “It’ll tell you when it’s happy. Too slow, it chews. Too fast, it screams.”

Now Leo was the old chief.

He grabbed the portable drill—a heavy, corded monster that was more like wrestling an angry dog than using a tool—and a set of bits.

“Cortez!” he shouted. “You done with that canvas?”

“Almost!” came the reply. “Chief, you sure you don’t want it bigger?”

Leo looked at the crack.

He thought about time.

“Make two squares,” he said. “One foot, then another a little bigger. We’ll layer them. Belt and suspenders.”

He knelt in the freezing water and pressed his hand against the hull near the crack.

The steel there was firm. Cold. The vibration of the ship tickled his palm.

“Chief?” one of the other machinist’s mates said. “Need a hand?”

Leo nodded.

“I need two volunteers who aren’t afraid of getting very wet,” he said. “One to hold the backing plate, one to help with the drill. Everyone else, clear the area. If this goes sideways, I don’t want to take half the crew with us.”

Two hands shot up.

“I’m here,” said McBride, a barrel-chested machinist with arms like ropes.

“I’m here,” said Cortez, voice tight but steady, canvas patch in hand now, edges ragged where he’d cut them.

Leo eyed them.

“You sure?” he asked.

McBride grinned.

“Better than sitting around listening to the squealing,” he said.

Cortez swallowed.

“My mom always wanted me to be a tailor,” he quipped weakly. “This is… close enough.”

Leo snorted.

“Fine,” he said. “McBride, you’re on the outside plate. Cortez, you’re with me on the drill and canvas.”

Connors blinked.

“Outside plate?” he repeated.

Leo pointed up at the hull curve.

“We can’t get to the outside of the hull,” he said. “But we can cheat. We’ve got some scrap steel strips from that pump rebuild. We’ll slide them under the frames from this side, behind the crack, like a splint. They’ll act as backing plates. Canvas on this side. Steel on the other. Studs through both.”

Connors shook his head slowly.

“You make it sound like sewing up a shirt,” he said.

Leo smiled thinly.

“Pressure’s just very rude fabric,” he said. “It keeps pulling on the seams.”

Minutes blurred.

Leo worked in a pocket of controlled chaos, the rest of the submarine receding to a distant hum. Voices came and went at the edge of his hearing—the captain conferring with the diving officer, the sonar man calling out new splashes, the cook praying softly under his breath—but the only world that mattered was the one framed by the arc of the hull and the spread of canvas in his hands.

They slid the scrap steel strips into place, fingers numb from cold. McBride fed them from one side of the frame; Cortez caught them on the other. They wedged against the inside of the hull, pressing firm and stubborn against the steel.

“Good,” Leo muttered. “Now hold that.”

He pressed the first canvas square against the crack.

Water soaked it in an instant, darkening it. The icy spray hit his face. He blinked it away.

“Mark it,” he said.

Cortez, teeth chattering, held the canvas steady while Leo pressed the blunt ends of three bolts against it in a rough triangle around the crack.

“Here, here, and here,” Leo said. “We drill there.”

He pulled the canvas away.

The hull waited, damp and unforgiving.

Leo fitted the biggest bit into the chuck of the drill.

He took a breath.

“Keep it straight,” he told himself. “Let the bit work. Don’t rush.”

Then he squeezed the trigger.

The drill roared to life, vibrating in his hands.

He pressed it against the steel a few inches from the crack, the bit biting into the metal with a high, gritty squeal. Chips spun away in silver curls, mixing with the spray.

The hull shuddered as another distant charge went off, but the bit stayed true.

“Come on,” Leo muttered. “Come on, girl. Hold together.”

He felt the pressure ease as the bit punched through into the thin gap between the hull and the backing plate strip.

“Through!” he shouted.

He yanked the drill back.

McBride, on the other side of the frame, slid a threaded stud through the hole from below. It poked out inside like a stubborn finger.

Leo grabbed it, spun a washer and nut onto it in quick motions.

“Next hole!” he barked.

They drilled two more, the drill screaming now, hot in his hands.

Every time he pressed it to the hull, a small part of his brain whispered that he was insane. That he was weakening the very thing standing between them and a swift, crushing end.

The rest of his brain shouted that they were going to lose the hull anyway if they didn’t slow the crack.

Between those arguments, his hands worked.

At last, three studs stood proud around the crack, their threads shining.

“Canvas,” he gasped.

Cortez slapped the patched square into his hand.

It trembled.

He laid the canvas over the crack, lining it up with the studs by feel.

Then he slid huge, flat washers over each protruding rod, followed by heavy, hexagonal nuts.

“Wrenches!” he snapped.

Two appeared in his hand.

He and Cortez began to tighten.

Slowly, the washers pressed the canvas against the hull.

Slowly, the canvas bulged, forming a crude, dark blister.

The spray lessened. The sheet of water became a fan. Then a hard, angry mist.

Leo tightened until his arms shook.

“Again,” he panted.

They added the second, larger square of canvas over the first, another set of washers, another round of tightening. The patch layered up like a crude shield.

The stream dwindled to a series of high-pressure weeps, spraying from the edges of the patch instead of a single screaming crack.

“Pump’s catching up, Chief!” someone yelled. “Bilge level’s dropping a little!”

Leo sagged back on his heels.

His fingers were numb. His eyes burned.

He pressed his palm against the canvas patch.

It was rock-hard under his hand, pushing back with the angry strength of the sea outside.

“Hold,” he whispered. “Please.”

The Hawthorn did not suddenly become safe.

The hull still groaned. The ocean still pulled at every plate, every seam, like a giant thing trying to crush a stubborn toy.

But they had bought something precious: time.

In the control room, the captain stood over the chart table, jaw clenched.

“We can’t stay at three hundred with a compromised hull,” he said quietly to the diving officer. “We need to come up. Even fifty feet buys us a little breathing room.”

“Sir,” the diving officer replied, “if we come up, we risk being detected.”

The sonar man swallowed.

“Sir,” he said, “the last string of charges was farther off. They might think we’re already done.”

The captain stared at the depth gauge, at the green stripe marking their current depth.

He reached for the intercom.

“Chief Ramirez,” he said. “Report.”

Leo, still kneeling by the patch, grabbed the handset with stiff fingers.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“How’s your canvas trick holding?” the captain asked.

Leo looked at the patch.

He felt it humming against his palm, a low vibration that matched the song of the hull.

“We slowed the leak,” he said. “She’s not happy. But she’s holding—for now.”

“Is it safe to take her up?” the captain asked.

Leo hesitated.

“Safe?” he repeated. “Sir, that word retired when we left port.”

A few of the men nearby snorted weakly.

“But,” Leo continued, “if we stay here, that crack’s going to keep working. If we go up slow, keep her balanced… I think we’ve got a better shot.”

“How much better?” the captain asked.

Leo exhaled.

“Enough to be worth trying,” he said.

There was a pause.

“All right,” the captain said. “We’ll take her up twenty feet at a time. Nice and gentle. You keep that patch talking to you, Chief. If it starts shouting, you let me know.”

“Yes, sir,” Leo said.

He hung up.

“Did you just tell the captain your patch talks?” Cortez whispered.

Leo smiled tiredly.

“I’ve been listening to this boat for two years,” he said. “She and I are on speaking terms.”

The next hour was a slow, careful climb out of danger.

“Make your depth… two-eighty,” the diving officer called.

“Two-eighty, aye,” the helmsman replied, hands steady on the controls.

The submarine angled up the slightest bit, like a sleeping whale deciding to rise.

The depth gauge’s needle crept.

At two-eighty, they leveled off.

The hull’s squeal dropped half a note.

Leo felt it under his hand on the canvas, in the floor under his knees.

“She likes that,” he said.

“Make your depth… two-sixty.”

The process repeated.

Two-sixty. Two-forty. Each step made the boat feel a fraction lighter, though Leo knew intellectually that they were still deep under enough water to turn the hull into scraps if they made one stupid move.

At two hundred, the captain allowed himself a shallow breath.

“Hold her there,” he said. “We wait.”

They waited.

No more depth charges came.

The sonar man reported distant propeller noise, then nothing.

After what felt like an eternity, the captain gave the order.

“Bring us up to periscope depth.”

The Hawthorn rose.

The canvas patch hummed.

Leo stayed with it all the way up, hand pressed to the damp fabric like a doctor feeling a pulse.

When the boat finally broke the surface, waves slapping against her sides, the hull seemed to sigh.

In the control room, the hatch cracked open, and a slice of gray daylight appeared.

Fresh air poured in.

A cheer went up, ragged but real.

In the engine room, a dozen men sagged against pipes and bulkheads, eyes closing, shoulders dropping.

Cortez laughed, the sound too high.

“We’re not fish food,” he said. “We’re not—”

His laughter turned into something else for a moment, then smoothed out as he scrubbed at his face with wet hands.

Leo patted the canvas one last time.

“Good work, girl,” he said.

McBride eyed the patch.

“Chief,” he said, “I’m never making fun of you for saving old bolts again.”

Leo grinned.

“You can still make fun of me for hoarding coffee,” he said.

Then he slumped back, suddenly, deeply tired.

The canvas patch stayed in place all the way back to port.

They didn’t trust it enough to stress the hull again, but it kept the crack from widening as they limped home under their own power, surfaced most of the way.

When the Hawthorn docked, the yard workers stared at the ugly bulge of canvas and steel on her side as she settled into the berth.

“What in the world is that?” one of them muttered.

“Chief’s autograph,” McBride said proudly.

Within twenty-four hours, the patch was removed, the crack was welded properly, and the engineers were writing long reports with words like “unauthorized hull modification” and “field-expedient repair.”

Leo spent most of those twenty-four hours asleep.

When he finally got hauled in front of a board of officers to explain himself, he stood at attention in his best uniform, canvas scrap in a paper bag at his feet.

The senior officer, a commander with unreadable eyes, tapped a pen on the table.

“Chief Ramirez,” he said, “do you understand why you’re here?”

Leo swallowed.

“To answer for drilling holes in your boat, sir,” he said.

There was a ripple of amusement around the table.

“That’s one way to put it,” the commander said. “The other is: seventy-eight men came back on that submarine. Some of them are writing home about a canvas patch and a mechanic who refused to let the ocean have them. That tends to attract attention.”

Leo felt his ears heat.

“I did what I thought needed doing, sir,” he said. “If I’d had a proper repair kit, I’d have used it. I had canvas and bolts.”

“Canvas, bolts,” the commander said, flipping through papers. “And your… ‘backing plate splint.’ And three new holes in the hull just inches from a compromised seam.”

He looked up.

“Do you know how many regulations that violated?” he asked.

Leo opened his mouth. Closed it.

“Several, sir?” he ventured.

The commander smiled suddenly.

“More than I care to count,” he said. “But regulations are written by men who expect their boats to be perfect. War is written by the ocean and the enemy. They don’t read our manuals.”

He set the pen down.

“You will receive an official letter of commendation,” he said. “It will say a lot of careful things about ‘initiative’ and ‘courage under pressure.’ It will not mention the phrase ‘canvas patch’ because the lawyers had heart palpitations when they saw your sketch.”

There was a muffled chuckle.

The commander’s face sobered.

“Unofficially,” he said, “if you ever find yourself in that situation again, I expect you to use the same stubborn brain that kept that boat from breaking open. Understood?”

Leo swallowed.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“Good,” the commander said. “You’re dismissed.”

As Leo turned to go, the commander added, “Chief?”

“Yes, sir?”

The commander nodded at the paper bag.

“Keep that scrap of canvas,” he said. “Something tells me people are going to want to see it one day.”

He was right.

They did.

At first, it was just the crew.

On liberty, in bars that smelled of spilled beer and cheap soap, men would clap Leo on the back and say, “Tell them about the patch, Chief.” He’d shake his head and let someone else talk.

Then it was the base newspaper.

They ran a short piece: “Mechanic’s Quick Thinking Saves Boat.” It mentioned “improvised sealing” and “field repair.” It did not mention drilling holes in the hull.

Then, years later, a historian.

Then a television producer.

Then the internet.

By the time Leo was eighty, the story had been boiled down to a neat sentence that fit nicely in headlines and social media posts:

“How one mechanic’s canvas patch saved 78 sailors from a sinking submarine at 300 feet.”

The sentence followed him.

Into grocery stores, where strangers squinted at him and then snapped their fingers.

“You’re that guy, aren’t you?” they’d say. “The canvas patch guy.”

Into the church hall, where kids in school projects asked if they could interview him “for a video we’re doing.”

Onto a stage at a veterans’ convention, where a host with perfect hair introduced him with a flourish.

“He broke the rules,” the host said. “He drilled into a submarine’s hull under extreme pressure. And he saved every man on board. Please welcome Chief Leo Ramirez.”

Leo shuffled to the microphone, leaning on his cane.

He’d long since learned to be suspicious of the way people told his story.

Some made it sound like a puzzle solved in a cozy workshop.

Some made it sound like a daredevil stunt.

Few liked to sit with the reality: that his hands had shaken on the drill, that he’d tasted fear like metal, that the ocean had been less than a finger’s breadth away.

A young man sat onstage with him this time. Dr. Amy Kwan, the program said. Naval engineer. Author of “Designing for Depth: Lessons from Submarine Incidents.”

The host turned to her.

“Dr. Kwan,” he said, “you’ve written about the ‘canvas patch incident,’ as they call it in engineering circles. Some people say it’s the ultimate example of ingenuity under fire. Others say it shows dangerous flaws in how we design and maintain our submarines. What’s your take?”

The atmosphere shifted.

It became serious. Tense.

Leo could feel it in the way the audience leaned in.

Dr. Kwan folded her hands.

“First,” she said, “it’s an honor to be onstage with Chief Ramirez. Without what he did, we wouldn’t be having this discussion.”

There was a murmur of agreement.

“But,” she continued, “as an engineer, I have to look at the bigger picture. The fact that a submarine at test depth suffered a hull seam crack suggests manufacturing or maintenance issues. The fact that the only available solution was an improvised patch suggests gaps in damage-control planning.”

She glanced at Leo.

“And the fact that we’ve turned it into a legend,” she said, “risks sending the message that we can rely on improvisation instead of planning.”

The host raised his eyebrows.

“Chief?” he said. “What do you think when you hear that?”

Leo adjusted the microphone.

“I think she’s not wrong,” he said bluntly.

The room rustled.

He smiled faintly.

“Boats shouldn’t crack at three hundred feet,” he said. “We all knew it. I knew it when the water hit me in the face. Part of my brain was very mad about the design while the rest was trying not to drown.”

A ripple of laughter loosened the air.

“I also think,” he went on, “that you can plan until your pencils break, and the sea will still find a way to surprise you.”

Dr. Kwan nodded.

“That’s exactly the tension,” she said. “No pun intended.”

The host leaned forward.

“Tension?” he repeated.

“In engineering circles,” she explained, “this incident has sparked arguments for decades. Some say, ‘Look at the ingenuity—this is what experience and creativity can do.’ Others say, ‘We should never have put him in a position where he needed to do that.’ The argument gets… heated.”

“You mean engineers arguing?” the host joked. “I thought you all just sent each other memos.”

Dr. Kwan smiled.

“You’d be surprised,” she said. “I’ve seen people raise their voices over this more than once. There was one symposium where a senior designer and a younger safety officer nearly stopped speaking to each other over whether we should even mention the canvas patch in official training.”

The host turned back to Leo.

“How do you feel about that?” he asked. “Knowing that your patch has become a kind of… battleground in design philosophy?”

Leo shrugged.

“I’m just glad the battleground is in a conference room and not in a flooded engine room,” he said. “If my mess can help them build better boats, they can argue over it all they want.”

Dr. Kwan’s expression softened.

“That’s part of why I wanted to be here,” she said. “Sometimes, when we argue over cases like this, we forget there were actual people behind the ‘incident report.’ It becomes a diagram, a set of bullet points.”

She looked at Leo.

“Hearing you talk about your hands shaking gives me more context than a hundred technical drawings,” she said.

Someone in the audience shouted, “He’s a hero! That’s all the context you need!”

The room muttered agreement.

Dr. Kwan shook her head gently.

“He is,” she said. “But if we stop there, we do him a disservice. We make it sound like heroism is a substitute for good design, instead of a last line of defense when design fails.”

Leo nodded slowly.

“Heroism is expensive,” he said. “In nerves, in sleep, in… other things. You don’t want to be budgeting for it.”

The host seemed slightly unsettled by the direction.

“So, Chief,” he said, looking for safer footing, “when people online share the story—‘Mechanic’s canvas patch saves 78 sailors at 300 feet’—does that bother you?”

Leo thought about it.

“A little,” he said.

He heard the crowd shift, surprised.

“I’m proud I helped keep my crew alive,” he said quickly. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m glad the story gives people something to talk about besides the latest bad news. But the way it gets told… sometimes it sounds like a magic trick. Like I pulled a rabbit out of a hat. That’s not how it felt.”

“How did it feel?” Dr. Kwan asked quietly.

Leo’s hands rested on the top of his cane.

“Cold,” he said. “Loud. And… very small. Like I was a tiny thing between something I cared about and something that didn’t care about us at all.”

The room was very still.

On the screens, somebody’s phone camera showed his lined face in close-up, eyes bright.

“I didn’t think, ‘Wow, I’m about to make history,’” he said. “I thought, ‘If this doesn’t work, seventy-eight families are going to get telegrams.’”

He looked at Dr. Kwan.

“So when you argue about my patch in your conferences,” he said, “remember those families too. Not just the stress on the steel.”

She nodded.

“I will,” she said.

After the event, in the green room, Dr. Kwan handed him a book.

“This is for you,” she said. “It’s a copy of my latest. There’s a chapter on your incident. I tried to do it justice. If I didn’t… you can send me a strongly worded letter.”

He chuckled.

“Don’t tempt me,” he said.

He flipped it open, thumbing past diagrams and photographs until he found a heading that made him snort:

“Case Study: The Canvas Patch and the Limits of Planning.”

Underneath, a black-and-white photo: a younger Leo than he remembered being, shirtless, grinning weakly in front of a hulking diesel engine, a smear of canvas visible behind him.

Dr. Kwan had underlined a sentence.

“In the end, the choices made in that engine room were not a triumph of improvisation over engineering, but a human response to a system pushed beyond its limits.”

“Not bad,” he said.

“There’s a quote from you at the end of the chapter,” she said. “From an interview you did years ago.”

He skimmed.

There it was.

“If I’m remembered at all,” it read, “I’d rather it be as the guy who tried to keep his boat and his people together with whatever he had, not as the guy with the magic patch.”

Leo smiled.

“Thank you,” he said.

“For what?” she asked.

“For turning me back into a person,” he said. “At least on paper.”

Years later, when Leo was gone, the canvas patch lived on.

Not the original—that had mildewed away decades before. But a carefully recreated section, built from his sketches and the recollections of his shipmates, hung in a glass case at a naval museum.

Beside it, the real scrap: a square of stained, stiffened canvas with three rusted bolt holes, edges frayed.

A small plaque read:

Canvas Patch from USS Hawthorn (Replica Arrangement, Original Material)

Improvised interior reinforcement used by Chief Motor Machinist’s Mate Leo Ramirez during a hull seam leak at depth.

This temporary measure slowed flooding long enough for the submarine to ascend to a safer depth, contributing to the survival of all 78 crew members on board.

The incident has been the subject of extensive discussion in engineering and ethics circles. As Chief Ramirez later said:

“It wasn’t magic. It was a bad situation, a scrap of canvas, some bolts, and a crew that didn’t want to give up.”

Visitors stopped, read, and moved on.

Some shook their heads in amazement.

Some snapped photos.

A few—especially those with engineering backgrounds—lingered, tracing the shape of the patch with their eyes, imagining forces and stresses, imagining a man kneeling in cold water with a drill in his hands and a whole crew behind him.

On certain days, school groups came through.

A teacher would stand in front of the display and say, “They mocked his idea at first. They said he was crazy to drill into the hull that deep. But he understood the boat and the materials better than anyone. He also understood what was at stake.”

A kid would raise a hand.

“Was he a hero?” they’d ask.

Sometimes, the guide would say yes without hesitation.

Sometimes, they’d pause.

“He was a person,” they’d say, “who met a terrifying moment and did the best thing he could think of, even though it scared him. We have a word for that. But we should also remember he spent the rest of his life thinking about what happened down there.”

In that way, the story kept its edges.

Not just the neat headline.

Also the cold water.

The squealing hull.

The arguments in conference rooms.

The seventy-eight men who climbed out of that submarine and into daylight because a mechanic with sore hands and a stubborn mind refused to accept that a crack in the hull was the end of the story.

THE END

News

How a Fortress Prison Built to Silence “Enemies of the Reich” Accidentally Became a Secret University of Freedom, where Socialists, Catholics, and Conservatives Fought Over What Democracy Should Mean—and Carried Those Serious, Tense Arguments into the New Europe

How a Fortress Prison Built to Silence “Enemies of the Reich” Accidentally Became a Secret University of Freedom, where Socialists,…

How a Devoted Nazi Military Engineer Built War Roads Across Europe, Then Lived Long Enough to Watch Those Same Highways Become the Skeleton of a Peaceful Union He Never Imagined

How a Devoted Nazi Military Engineer Built War Roads Across Europe, Then Lived Long Enough to Watch Those Same Highways…

How a Devoted Nazi Army Surgeon Entered an American POW Hospital Expecting Revenge, Discovered a Forbidden Ledger of Compassion, and Sparked a Fierce Moral Battle That Outlived Barbed Wire and Surrender

How a Devoted Nazi Army Surgeon Entered an American POW Hospital Expecting Revenge, Discovered a Forbidden Ledger of Compassion, and…

How German Women POWs Froze When an American Sergeant Ordered “Face the Wall…”, Why They Started Crying at the Sound of English Behind Them, and How That Moment Became a Lifetime Argument Over Fear, Guilt, and What the Order Really Meant

How German Women POWs Froze When an American Sergeant Ordered “Face the Wall…”, Why They Started Crying at the Sound…

How Japanese Women POWs Once Screamed “They’re Going to Drown Us!” When American Trucks Rolled Toward a Flooded River, and How That Terrifying Ride Turned Into Decades of Argument About Rumors, Mercy, and What We Choose to Remember

How Japanese Women POWs Once Screamed “They’re Going to Drown Us!” When American Trucks Rolled Toward a Flooded River, and…

How German Women POWs Whispered “They’ll Leave Us to Freeze” in a Whiteout Blizzard, Until American Guards Slung Them on Their Backs and Forced Everyone to Live Through a Night No One Could Forget

How German Women POWs Whispered “They’ll Leave Us to Freeze” in a Whiteout Blizzard, Until American Guards Slung Them on…

End of content

No more pages to load