How a Fortress Prison Built to Silence “Enemies of the Reich” Accidentally Became a Secret University of Freedom, where Socialists, Catholics, and Conservatives Fought Over What Democracy Should Mean—and Carried Those Serious, Tense Arguments into the New Europe

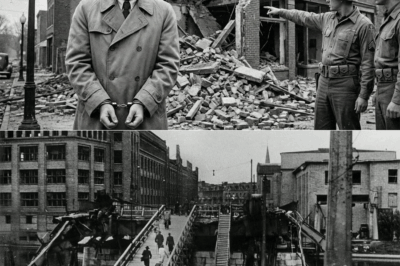

By the time the train doors clanged open, the fog had thinned enough for Otto Reimann to see the outline of the prison.

It rose out of the pine forest like a stone ship, all sharp angles and blank windows. High walls. Watchtowers. A gate that looked less like an entry and more like a mouth.

“Fortress Falkenberg,” the guard beside him said in accented German. “Enjoy your stay, Herr Abgeordneter.”

He said the last word—member of parliament—with a smirk, like a joke whose punch line was the clink of Otto’s handcuffs.

Otto stepped down onto the wet platform.

He was forty-eight years old and had spent half his life in politics. He had survived Weimar brawls, beer hall debates, street marches that had turned ugly. He had never imagined that his last glimpse of the German countryside as a free man would be pine trees dripping in autumn rain.

He adjusted his glasses, their frame slightly bent from the “interrogation” in Berlin, and straightened his back.

He was not brave, he told himself.

He was simply stubborn.

When the Reichstag fire decree had landed, when the new leaders had said “emergency measures,” he’d been one of a shrinking handful who had stood up in the half-empty parliament and said, “No.”

He’d believed, for a brief, naïve moment, that the constitution he’d helped draft would protect him.

Then the brown-shirted men had come to his apartment at dawn.

Now they marched him through the gate of a prison built in another century and repurposed for this one.

Inside, the air was colder.

Or maybe that was just his bones catching up with the facts.

Falkenberg had once been a military fortress.

Thick walls of grey stone.

Narrow slits for windows.

Cells originally designed to hold deserters and mutineers.

The new regime saw its potential immediately.

By 1934, the place was full.

There were communists and social democrats, monarchists who had muttered in the wrong salons, trade unionists, Catholic priests, Protestant pastors, journalists who had written one editorial too many, and even a few former Nazi Party members who had been purged when their loyalty wavered in the wrong direction.

“They call it the ‘Museum of Unfit Germans,’” one guard joked to another as they walked Otto down the corridor. “All the old models in one place.”

The guard laughed.

The prisoners did not.

Otto’s cell was small but not yet overcrowded. Two beds, one above the other. A latrine bucket. A tiny barred window that gave onto a strip of sky and the upper branches of a pine tree.

His cellmate lay on the lower bunk, book open on his chest.

He was in his thirties, with dark hair going prematurely grey at the temples and a small scar on his chin.

He looked up as the door clanged shut.

“New?” he asked.

“Yes,” Otto said. “Reimann. Otto.”

“Markus Levy,” the man said. “Formerly of the Social Democratic Party. Currently of Cell 14B.”

Otto blinked.

He knew the name.

Markus had been a fiery young speaker in the Reichstag, famous for his sharp tongue and his refusal to be intimidated. Otto had watched him once from across the chamber, cutting a far-right deputy down to size with nothing but facts and dry sarcasm.

Now he wore a prison jacket and had dark circles under his eyes.

“The famous Otto Reimann,” Markus said, sitting up. “The man who thought he could talk them out of dismantling the republic.”

Otto bristled.

“I thought the law would hold,” he said. “I was wrong.”

“Welcome to remedial education,” Markus said. “The syllabus is limited but intense.”

He swung his legs over the side of the bunk.

“Lunch is thin soup and thick rumors,” he added. “Dinner is the same. Breakfast is memories.”

He smiled faintly.

“Also, we have seminars,” he said. “Secret ones. They don’t know that.”

“Seminars,” Otto repeated. “In prison.”

“Where else?” Markus shrugged.

He tapped the book on his chest.

It was a battered, smuggled copy of the constitution Otto had helped write ten years earlier.

“Someone has to remember how this was supposed to work,” Markus said.

The first “class” Otto attended met in the laundry room.

It smelled of damp cloth and soap.

Steam rose from big basins where prisoners scrubbed uniforms that had once been theirs and were now part of the institution that held them.

The guards, bored with the monotony, often hovered at the door, chatting, smoking.

Inside, underneath the hiss of boiling water and the slap of wet cloth, conversations flowed that were far less visible.

Markus led him to a corner where several men were hunched over a crate that served as a table.

“Gentlemen,” Markus said. “This is Otto Reimann. Former Catholic Center Party. Co-author of that noble document we all waved around for a decade.”

One of the men snorted.

An older fellow with a priest’s posture and hands roughened by work nodded politely.

Another—a lean man with sharp cheekbones and dark, intense eyes—tilted his head.

“Communist,” Markus said quietly to Otto. “Name’s Ernst Vogel. Don’t let the Party line fool you; he actually reads.”

Ernst smiled thinly.

“And you,” he said, “are the one who thought a constitution without economic rights could survive storms.”

Otto opened his mouth.

He closed it again.

It was not the first criticism he’d heard along those lines.

“Today’s topic,” Markus said briskly, pulling out a scrap of paper filled with cramped writing, “is: ‘What went wrong? And more importantly, what do we do differently if we ever get a second chance?’”

Otto stared.

The question felt almost obscene.

Second chance.

As if there would be an “after.”

As if they weren’t all just… waiting.

But the others nodded, even the priest.

“We have time,” the priest said. “And minds. If we waste both, then we might as well have joined them.”

He said “them” without spitting, but the contempt was clear.

Farmers had their words for pests.

Urban intellectuals had theirs.

Otto looked around.

“We’re locked in a fortress,” he said. “Cut off from the country. Cut off from any real influence. The men outside decide everything. We are ants in a jar.”

“Ants still think,” Ernst said. “And ants make trails. Ideas are trails. When the jar breaks, where do you want people to run? Back to the same patterns?”

His eyes were hard.

Otto felt a spark in his chest—anger, defensiveness, something else.

“The center held as long as it could,” he said. “We tried to balance extremes. We tried to—”

“You compromised with men who wanted to strangle you,” Ernst cut in. “You signed away emergency powers because you believed in civility.”

“That’s enough,” Markus said. “We could spend years fighting over who failed first.” He smiled humorlessly. “We probably will.”

“But our real task,” the priest said softly, “is to imagine what we would tell our grandchildren if they ask, ‘Why did you let it happen? And what did you learn?’”

The word “grandchildren” landed like a small stone in Otto’s gut.

He had one already—barely a year old when he’d last held her. A tiny thing with a shock of dark hair and his daughter’s eyes.

He didn’t know if she was still alive.

He didn’t let himself dwell on it.

Not if he wanted to stand upright.

“Fine,” he said. “We talk about that. About why we failed and what we want instead. But what good is it if these conversations die with us in this laundry room?”

Markus’s smile widened slightly.

“Oh, they won’t,” he said.

He tapped his forehead.

“We’re embedding them here,” he said. “And here.”

He tapped his chest.

“And if any of us walk out of this place alive, we’ll carry them further.”

He spread his hands.

“Welcome to the Falkenberg Academy,” he said. “Enrollment is limited. Graduation is… uncertain.”

The men chuckled.

The sound was dry, brittle.

But it was laughter.

Otto, despite himself, felt something in his ribs loosen.

The “Academy” was a shifting thing.

Sometimes it was the laundry room.

Sometimes it was the carpentry shop.

Sometimes it was a corner of the yard, disguised as a game of chess played with carved bits of soap.

The topics ranged widely.

One week, they dissected the mistakes of Weimar—from proportional representation that fragmented parliaments to Article 48, the “emergency clause” that had become the trapdoor under the republic.

“We wrote that clause,” Otto said bitterly one afternoon, pressing his thumb into the damp wood of a table. “We thought we were protecting against paralysis. We never imagined someone would use it as a ladder up and then pull it after him.”

“We imagined it,” Ernst said. “We just didn’t have the votes to stop it.”

He flashed Otto a brief, humorless grin.

“Don’t worry,” he added. “We blamed our leadership, too.”

Another week, they argued about what democracy should mean beyond ballot boxes.

“Is it enough just to have votes?” Markus asked. “If those votes can be bought with fear and hunger?”

“Of course not,” Ernst said. “Without economic democracy, political democracy is a shell.”

“You and your shells,” Otto muttered. “Without rule of law, your economic democracy is just another form of tyranny.”

The priest—Father Josef—watched them with patient amusement.

“You’re both right,” he said. “And both wrong.”

“Helpful,” Markus said dryly.

“No, truly,” Josef said. “Power corrupts whether it is in factories or parliaments. Any system that doesn’t anticipate that and build in brakes—with values, with institutions, with habits of restraint—will eventually disappoint.”

“The problem with you Christians,” Ernst said, “is that you talk about ‘sin’ and ‘corruption’ as if they’re inevitable. It makes you lazy.”

“And the problem with you revolutionaries,” Josef replied evenly, “is that you think a new system erases old flaws in human nature. It makes you arrogant.”

The argument that followed was exactly what Markus had warned would happen—serious and tense.

Voices rose.

Hands gestured.

At one point, Ernst slammed his palm on the crate so hard a tin cup fell over, making a sharp, metallic clatter.

A guard near the door glanced over.

“Keep it down,” he barked.

“We’re arguing about chess moves,” Markus said smoothly. “The comrade here believes in sacrificing his queen. I say it’s bad strategy.”

The guard shook his head.

“Idiots,” he muttered, and moved on.

As the footsteps faded, the tension eased.

Otto let out a breath.

“We’re fools,” he said. “We sit here planning constitutions we may never see while men upstairs decide whether we get supper tomorrow.”

Markus shrugged.

“Men upstairs decided a lot of things before,” he said. “We still wrote constitutions.”

He gestured around.

“Anyway,” he added, “what else would you rather do? Count the stones in your cell?”

That night, back in Cell 14B, Otto lay awake.

The piece of sky visible through the tiny window was clear for once.

A star winked.

He thought of all the people—including himself—who had once believed the old system could be repaired with a few compromises, a few clever formulas, a few decent speeches.

He thought of the brown banners, the fear in the streets, the way one man’s voice had drowned out whole chambers of debate.

“Next time,” he whispered to the darkness, “we build stronger walls around power.”

He didn’t sleep well.

Dreams of walls, both stone and legal, chased each other through his mind.

The prison administration tolerated some things and crushed others.

They tolerated chess.

They tolerated jokes, as long as they weren’t about the wrong people.

They did not tolerate smuggled leaflets or organized hunger strikes.

One afternoon, a new batch of prisoners arrived—gaunt, angry men from a failed plot in the army.

“They nearly killed him,” someone whispered in the yard.

“Nearly,” someone else spat. “Nearly doesn’t count.”

One of the new arrivals, a stooped colonel with haunted eyes, was assigned to the laundry crew.

He listened for a week before joining the “Academy.”

“You talk as if there will be a ‘later,’” he said one day, voice rough.

“There will be,” Ernst said stubbornly. “History moves. Regimes fall. Lines shift. The Reich is not the sun. It will not burn forever.”

“We tried to shorten its life,” the colonel said. “We failed. And now, they call us traitors for attempting to save what was left of the country a different way.”

“Welcome to the club,” Markus said. “We were traitors the moment we insisted the law meant the same thing for everyone.”

The colonel’s mouth twisted.

“What is this school of yours teaching?” he asked. “How to be noble losers?”

“No,” Otto said quietly. “How not to make the same mistakes if we ever stop losing.”

He leaned forward.

“You were willing to kill a tyrant to preserve something,” he said. “What was that something?”

The colonel blinked.

“Germany,” he said automatically.

“And what is Germany, in your mind?” Ernst asked. “Soil? Flag? Laws? People? All of the above?”

The colonel frowned.

“I didn’t come here to be cross-examined,” he muttered.

Josef smiled gently.

“None of us did,” he said. “And yet.”

The colonel sighed.

After a long moment, he said:

“If I am honest, I wanted to preserve… a sense of order where the army answers to something besides one man’s will. I wanted a country where we are not sent to die in Russia because of his vanity.”

“A constitution, in other words,” Markus said. “With real limits.”

The colonel nodded begrudgingly.

“Then sit,” Ernst said, sliding over to make room on the crate. “Class is in session.”

The colonel laughed, a short, surprised bark.

“You men talk like lecturers,” he said.

“And you look like a man who has read Clausewitz and thinks it covers everything,” Otto replied. “We all have blind spots.”

Slowly, reluctantly, the colonel became one of their fiercest participants.

He brought a different perspective—one shaped by barracks and battlefields, by orders and their consequences.

He argued that any future democracy had to find a way to integrate the military without either idolizing or treating it as a permanent suspect.

“We don’t want another generation of officers who think the only way to save the country is in secret,” he said. “If we want them to swear to a constitution, that constitution better mean something.”

“Agreed,” Markus said. “And if we want them to feel that loyalty, maybe we shouldn’t treat them all as if they’re just waiting to march on parliament.”

The arguments grew richer, more complex.

The Academy’s “curriculum” expanded to include federalism, human rights, economic planning, education, media.

They drew imaginary diagrams of institutions on bits of torn sack.

They debated whether banning certain parties would protect or harm democracy.

“Can we outlaw those who want to outlaw everyone else?” Josef asked.

“We must,” Ernst said. “Otherwise they’ll use our freedoms to kill freedom again.”

“But who decides which parties are dangerous?” Otto countered. “That can go wrong very quickly.”

“In other words,” Markus said, rubbing his temples, “we are trying to design a system where no one can do what they did… including us.”

“Yes,” Josef said. “That is exactly what we are doing.”

Sometimes, exhausted, they simply sat in silence, listening to the distant clank of a gate, the cough of a sick prisoner, the mutter of a guard.

Even in those moments, the momentum of their thinking carried.

In the absence of official classrooms, they built one out of conversation.

In 1944, the war crept closer.

The faint rumble they’d sometimes heard underfoot—too distant to identify—became more frequent.

More prisoners arrived, some straight from bombed cities, smelling of smoke and plaster dust.

They brought news, in fragments.

Hamburg in flames.

Dresden gone.

Allies on the beaches.

Rumors of atrocities the prisoners in Falkenberg guessed at but had never seen.

Rumors of camps that made their stone fortress look like a boarding school.

One night, the guards were jittery.

Even their shouting had an anxious edge.

“Something has changed,” Markus whispered in the yard. “In their eyes.”

A few days later, an American plane roared low overhead.

A scrap of paper fluttered down, caught in the barbed wire.

A guard snatched it before anyone could see—but not before a few words were visible:

We are coming.

Hope flickered.

Fear did, too.

None of them had illusions about what armies did when they entered enemy territory.

But many, increasingly, believed that any “after” could not be worse than “now.”

When the first distant gunshots of artillery grew nearer, Falkenberg braced.

The guards disappeared.

The gates stayed locked.

Inside, in the cells, men waited.

“Will they shell the prison?” Lotte—one of the few women in a separate wing, allowed into the yard only on certain days—asked Josef through the bars.

“They have maps,” Josef said. “They know this is a prison.”

“Do they care?” she asked.

“Let’s hope their gunners are better at restraint than ours were,” he replied.

When the outer gate finally swung open, it was not to shellfire but to shouting in a language Otto recognized only from his school days.

English.

“Stay where you are!” an amplified voice called. “We will open the cells one by one. No rushing. No weapons. You are prisoners no more.”

Markus looked at Otto.

“Graduation day,” he murmured.

Otto’s legs shook when they walked through the gate into a yard that looked suddenly different.

Same walls.

Same pines.

Different flags overhead.

He felt like a fish dumped from a small, murky tank into a fast-moving river.

Free.

Disoriented.

The Americans processed them—photographs, names, quick questions about rank and affiliation.

Some were taken aside immediately for further questioning.

Others, including Otto, Markus, Ernst, Josef, the colonel, and Lotte, were herded to a separate compound.

“Politicals,” an American sergeant explained. “We don’t quite know what to do with you yet. You’re not just ordinary soldiers. You’re… interesting.”

He said it reluctantly, as if “interesting” were a dangerous diagnosis.

They spent weeks in that limbo.

Waiting.

Talking.

They knew their Academy had been a fragile thing.

They did not yet know that the real exams were ahead.

The years immediately after the war were confusing.

Germany—West and East—filled with parties both new and resurrected.

Old labels came back with new qualifiers.

“Social Democratic.”

“Christian Democratic.”

“Communist.”

“Liberal.”

Behind each stood men and women who had survived one storm and were now trying to build houses that wouldn’t blow down in the next.

Some of the veterans of Falkenberg’s Academy went East.

Ernst almost did.

“They are rebuilding from the ground up there,” he said one night in the shared barracks. “Land reform. Factories into workers’ hands. Your lot in the West will cozy up to the Americans and call it democracy while big capital runs the show again.”

“And your lot in the East will cozy up to Moscow and call it liberation while one party runs everything,” Markus replied. “How is that better?”

The argument, once again, got serious and tense.

In the end, Ernst made his choice.

“We’ve been in a prison together,” he said. “Now we must test our ideas in the open. You write your cautious constitutions. I’ll try to make sure workers can afford bread while reading them.”

They shook hands.

“It will not be as simple as you think,” Josef warned Ernst. “Be careful what you sign away in the name of justice.”

“Likewise,” Ernst said. “Be careful what you sacrifice in the name of stability.”

He left.

History would not be kind to his side of the experiment.

But that, in this moment at least, was still in the future.

In the West, constitutional assemblies convened.

Otto found himself staring at a familiar kind of paper.

Draft articles.

Proposed clauses.

“Basic Law,” they called it now, not “Constitution.” A psychological trick, some said—to suggest it was temporary until reunification.

For men like Otto, Markus, Josef, and the colonel, it was a second chance at their life’s work.

They were not the only voices in the room.

But their experience in Falkenberg gave them a gravity others lacked.

“You have actually tried some of these ideas under fire,” a younger delegate said. “Even if only on paper.”

“On soap,” Markus corrected. “And on laundry crates.”

He argued for stronger protections for basic rights.

“For a court that can strike down laws that smell too much like emergency decrees,” he said. “We gave the last leader too much rope. He hanged us with it. Let’s not do that again.”

Otto pushed for a federal structure that would make it harder for power to concentrate in one place.

“A strong central government is tempting,” he said. “We saw where that leads. Give regions real teeth. Make it messy. Messy is harder to hijack.”

The colonel spoke about the military.

“Make it clear, in the text, that any future army answers to parliament,” he said. “Not a man, not a party. The oath must be to the law, not to a leader.”

Josef pressed for explicit dignity clauses.

“Write it down,” he said. “That human dignity is inviolable. Make it the first article, not an afterthought. So that next time a bureaucrat wants to write ‘low priority’ next to someone’s life, he at least feels his pen tremble.”

They did not win every argument.

But they won enough.

When the new Basic Law was promulgated in 1949, some phrases would sound familiar to anyone who’d sat in the Falkenberg laundry room:

“Human dignity shall be inviolable…”

“All state authority is derived from the people…”

“The armed forces shall be subject to parliamentary control…”

Parties that sought to undermine the free democratic basic order could be banned by the Constitutional Court.

Emergency powers were carefully hedged, time-limited, subject to legislative oversight.

It was not perfect.

No document is.

But it was, undeniably, a product of men and women who had learned the hard way what happens when you give too much credit to good intentions and too little to bad systems.

As the decades passed, the prison at Falkenberg became many things.

For a while, it was simply… a prison.

Different flags flew overhead.

Different insignia on the guards’ caps.

Inside, people were still locked up for things the state didn’t like.

Some of those things were crimes.

Some were not.

Later, after reunification and rationalization of institutions, Falkenberg was decommissioned.

For a few years, it sat empty.

Windows broken by vandals.

Spray paint on the walls.

Grass growing in cracks between the stones.

Then someone had an idea.

“We should turn it into a memorial,” a local councillor said. “And maybe a museum. People forget too quickly what it meant.”

The idea, as ideas do, sparked arguments.

Some residents wanted to bulldoze the place.

“Why preserve that?” they asked. “It’s a scar.”

Others wanted to keep it exactly as it was.

“Don’t sanitize it,” they said. “Let people feel the damp.”

In the end, they did something in between.

They patched the roof.

They left some cells bare, some with exhibits.

They put up panels with photographs and text.

Names.

Dates.

Stories.

A corner of the laundry room was roped off with a sign:

“In this space, prisoners held informal discussions about politics, faith, and the future of Germany. Some of them later became leading voices in the creation of the Federal Republic’s Basic Law.”

Tour guides told visitors about Otto, Markus, Ernst, Josef, the colonel, Lotte.

They were composites, amalgams drawn from diaries, oral histories, official files.

They stood in for dozens of real people whose names had faded or gotten lost.

Not everyone liked the narrative.

Some critics said it made the prison look too… productive.

As if suffering were redeemed by later success.

Others said it exaggerated the building’s role.

“You’re telling this as if Falkenberg was the only crucible,” one historian complained. “Democracy had many midwives.”

They were right.

It did.

Still, the story of the “Academy” caught the public imagination.

Newspapers ran features with titles like:

“Inside the Fortress Where Democracy Was Rehearsed.”

Documentaries zoomed in on soap chess pieces and recreated late-night debates in moody lighting.

Online, people argued over whether the narrative was romanticized or inspiring or both.

“I’m tired of hearing about ‘good Germans’ now,” one commenter wrote. “They were in a Nazi prison. They’re still Germans. They didn’t stop the worst.”

“Isn’t the point that they tried to build better afterward?” another replied. “Or do we think people are damned forever?”

“If they helped design a system that kept us from falling back into dictatorship, that matters,” a third said. “Even if they didn’t get it right the first time.”

The argument, unsurprisingly, was serious and tense.

Some wanted to draw a hard line between victims and heroes.

Others insisted on messier categories.

Meanwhile, school groups traipsed through the old corridors.

Teenagers rolled their eyes, pretended to be bored, then went quiet when the guide closed a cell door for a moment to show how it sounded.

In the laundry room, some of them tried to imagine heated conversations under the hiss of boiling water.

“It’s weird,” one sixteen-year-old said, staring at the placard. “They were in prison, and they were doing… politics.”

“That’s exactly what politics is,” her teacher said. “Deciding how we want to live together, even when things are bad. Maybe especially then.”

On a grey afternoon in the early 2000s, an old man with a cane and a younger woman beside him walked into Falkenberg’s courtyard.

No one recognized him.

He liked it that way.

Otto Reimann—much older now, hair thin, hands shaky—stood under the pine tree visible from his old cell window.

His granddaughter read the plaque on the wall.

“You see?” she said. “They mention you. ‘One former member of parliament, imprisoned here, later became an important voice in constitutional debates.’”

He chuckled.

“They were generous,” he said. “I mostly shouted at people in committee meetings.”

She smiled.

“You shouted with reason,” she said. “That counts.”

They went into the laundry room.

The crate was gone.

The basins were dry.

But the air still smelled faintly of soap.

A group of visitors clustered around a guide who was describing the “Academy.”

“They met here,” the guide said. “They argued about federalism, human rights, the role of the military…”

He looked pleased with the list.

Otto could have added ten more topics.

He kept quiet.

His granddaughter glanced at him.

“What do you think?” she whispered. “Is this how it was?”

“No,” he said. “And yes.”

He gestured.

“The smell was stronger,” he said. “There were more guards. We had less hair and more fear.”

He tapped his forehead.

“But the arguments?” he said. “Those sound familiar.”

The guide quoted from a book.

“‘We built constitutions on soap and prayer,’” he read. “That was one prisoner’s description.”

Otto smiled.

“That one was Markus,” he said softly.

His granddaughter frowned.

“Do you ever feel… angry that they turn it into a story?” she asked. “Like it’s something neat and inspiring, when it must have been… awful.”

He took a breath.

“Sometimes,” he said. “Especially when people want to use it to pat themselves on the back. ‘Look how far we’ve come.’”

He looked at her.

“And sometimes,” he added, “I feel… grateful.”

“For what?” she asked.

“For the reminder,” he said, “that even in a stone fortress designed to shut people up, we still opened our mouths. That we talked about something other than our own suffering. That we learned.”

He leaned on his cane.

“I don’t want people to think Falkenberg ‘created’ democracy,” he said. “Democracy came from many places, many struggles. But I do want them to understand that those who defend it most fiercely are often the ones who have seen what it’s like without it.”

She slipped her arm through his.

“Do you…” she hesitated. “Do you think you did enough? Back then? Before?”

He stared at the floor.

“No,” he said. “If I had, I wouldn’t have ended up here.”

He met her gaze.

“But I did more later, because of here,” he said. “That has to count for something.”

They walked back out into the yard.

The sky was low and grey.

A drizzle began.

“Come on,” his granddaughter said. “Let’s get you inside. I don’t want you catching cold for the sake of symbolism.”

He laughed.

“Practical as ever,” he said. “You’d have done well at Falkenberg.”

She wrinkled her nose.

“I’ll take my seminars in warmer rooms, thanks,” she said.

Outside the museum, a bus pulled up.

A new group filed out.

The cycle continued.

Stories told.

Stories questioned.

Some visitors left thinking, “How inspiring.”

Others left thinking, “How complicated.”

Both were right.

Inside the old stone walls, the echoes of those long-ago debates still seemed to hum in the corners.

What went wrong?

What do we do differently?

How do we build a system that anticipates our worst impulses and trusts our best?

They were not questions unique to any one prison or one generation.

They were, and remain, the constant homework of anyone who dares call themselves a citizen.

Fortress Falkenberg had been built to keep voices in.

It had, unintentionally, become a place where voices sharpened.

Not into revenge.

Into resolve.

When people later spoke of “democracy’s fiercest defenders,” they often meant the ones on podiums, in parliaments, on television.

They rarely pictured men in threadbare jackets and women with coarse soap under their fingernails, arguing over imaginary articles in a laundry room that smelled of sweat and lye.

But in the long, complicated story of how Europe dragged itself out of its own wreckage, those invisible seminars mattered.

You could see traces of them in the preambles and clauses, in the court decisions and ministerial guidelines, in the reflexive flinches whenever someone in power said “emergency” too casually.

Inside a Nazi prison, inmates had become democracy’s fiercest defenders not because walls made them virtuous, but because walls forced them to decide what, beyond their own skins, was still worth fighting for.

They did not always agree.

Their arguments were often serious and tense.

But they had them.

And in the end, that may be the most important thing democracy ever asks of anyone:

Don’t stop arguing about how to do better.

Especially when you are tired.

Especially when you are scared.

Especially when the walls are closing in.

THE END

News

How a Devoted Nazi Military Engineer Built War Roads Across Europe, Then Lived Long Enough to Watch Those Same Highways Become the Skeleton of a Peaceful Union He Never Imagined

How a Devoted Nazi Military Engineer Built War Roads Across Europe, Then Lived Long Enough to Watch Those Same Highways…

How a Devoted Nazi Army Surgeon Entered an American POW Hospital Expecting Revenge, Discovered a Forbidden Ledger of Compassion, and Sparked a Fierce Moral Battle That Outlived Barbed Wire and Surrender

How a Devoted Nazi Army Surgeon Entered an American POW Hospital Expecting Revenge, Discovered a Forbidden Ledger of Compassion, and…

How German Women POWs Froze When an American Sergeant Ordered “Face the Wall…”, Why They Started Crying at the Sound of English Behind Them, and How That Moment Became a Lifetime Argument Over Fear, Guilt, and What the Order Really Meant

How German Women POWs Froze When an American Sergeant Ordered “Face the Wall…”, Why They Started Crying at the Sound…

How Japanese Women POWs Once Screamed “They’re Going to Drown Us!” When American Trucks Rolled Toward a Flooded River, and How That Terrifying Ride Turned Into Decades of Argument About Rumors, Mercy, and What We Choose to Remember

How Japanese Women POWs Once Screamed “They’re Going to Drown Us!” When American Trucks Rolled Toward a Flooded River, and…

How German Women POWs Whispered “They’ll Leave Us to Freeze” in a Whiteout Blizzard, Until American Guards Slung Them on Their Backs and Forced Everyone to Live Through a Night No One Could Forget

How German Women POWs Whispered “They’ll Leave Us to Freeze” in a Whiteout Blizzard, Until American Guards Slung Them on…

Why One German POW Woman Whispered “Please… Don’t Touch Me” During a Routine Exam, and How That Moment Forced American Doctors to Confront Trauma, Trust, and Their Own Assumptions

Why One German POW Woman Whispered “Please… Don’t Touch Me” During a Routine Exam, and How That Moment Forced American…

End of content

No more pages to load