HOA “Karen” Harassed My 9-Year-Old at the Bus Stop Over a Backpack and Hoodie, Then Tried to Lecture Me About “Neighborhood Standards” — She Didn’t Realize I’m the New Police Chief and Her Worst Nightmare

I’ve been a police officer for almost fifteen years and a police chief for six months.

In that time, I’ve dealt with just about every kind of person you can imagine—loud, angry, upset, scared, stubborn, confused. I’ve been yelled at, thanked, blamed, hugged, and once gifted a casserole from an older lady who thought I looked “too thin to chase anyone.”

What I wasn’t prepared for, somehow, was a homeowner association board member deciding my nine-year-old son was her new favorite problem.

This happened last month, but it feels like it’s still unfolding in slow motion in my brain. I typed it up for Reddit—because my sister insisted—and titled it something like: “HOA Karen Confronts My Child at the Bus Stop, Then Tries to Call the Cops… I Am the Cops.”

Here’s what went down.

1. The HOA, the Bus Stop, and My “Low-Drama” Plan

When I got offered the chief position in a neighboring town, my husband and I decided to move closer to my new station. We found what looked like a perfect neighborhood: quiet cul-de-sac, lots of kids, tree-lined sidewalks, decent schools.

There was an HOA, which I’m never thrilled about, but the fees were low and the rules seemed pretty standard on paper.

No crumbling fences, keep your lawn presentable, no parking boats on the front lawn forever. Fine.

We bought a small but cozy house, and my son, Eli, immediately fell in love with the idea that he could ride his bike to the park and take the school bus with other kids.

I work long hours, but I’m not usually out on patrol anymore. Still, because of my schedule and because my husband does shift work at the hospital, we decided the bus was the best option most mornings.

The bus stop is at the end of our street, by a little common area with a bench and one of those HOA bulletin boards that nobody reads unless there’s a picture of a lost cat.

The plan was this:

Eli walks two houses down to the bus stop.

The bus driver, who now knows him, picks him up.

I watch from our Ring camera and through the front window like a slightly overprotective hawk.

Low drama. Easy routine.

For the first two months, it was exactly that.

Then Marjorie entered the chat.

2. Meet the HOA’s Self-Appointed Sheriff

I didn’t meet her officially until later, but I’d noticed her.

Late fifties, always in pastel sweaters, hair that hadn’t changed style since the ‘80s, clipboard in hand more often than not. She walked the neighborhood like she was conducting inspections—even when she was just walking her dog.

You know the type.

Every street has at least one person who thinks the world would fall apart if they weren’t personally monitoring trash can placement.

The first time Eli mentioned her, it sounded harmless.

“There’s this lady who lives near the bus stop,” he said one afternoon while we had grilled cheese sandwiches. “She’s always outside. She talks a lot about the grass.”

“The grass?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “She says people are ‘ruining the landscaping’ if they cut across the corner of the hill. She told Zach he couldn’t sit on the stone wall.”

I shrugged.

“As long as she’s not bothering you, just be polite and leave the grass alone,” I said. “HOA people get nervous about grass.”

(This is what we call foreshadowing.)

For a while, it was fine.

Then, one Tuesday morning, I was halfway through a cup of coffee when Eli came home from the bus stop five minutes after he left.

His face was flushed, eyes shiny with that embarrassed-about-to-cry look.

“Bus didn’t come?” I asked, already reaching for my keys.

“No, it’s coming,” he said quickly. “I just… I forgot something.”

He hadn’t forgotten anything. His backpack was on his shoulders, shoes tied, hoodie zipped halfway up.

My mom brain pinged.

“What happened?” I asked, kneeling down to his level.

He hesitated, then blurted, “That lady yelled at me.”

“Yelled at you?” I repeated, my stomach tightening. “What did she say?”

“She said I wasn’t allowed to wait at the bus stop with my hood up,” he said, scowling. “She said it looked ‘suspicious’ and that I was ‘making the neighborhood feel unsafe.’”

My jaw clenched.

“She used those words?” I asked carefully.

He nodded, eyes filling.

“And when I tried to say I was just cold, she said kids who ‘hide their faces’ are always the ones causing trouble, and she was going to report me to the HOA and the police.”

I took a deep breath, counting to five in my head like I tell my officers to do when a situation irritates them.

“Did you say anything back?” I asked.

“I said my mom wouldn’t like her talking to me like that,” he muttered. “Then she asked who my mom is and I said your name. She said she didn’t care, rules are rules, and if I didn’t take my hood down she’d ‘have me removed from the property.’”

He made air quotes around “removed from the property,” which would’ve been funny if I wasn’t trying to keep my blood pressure under control.

Our “property.”

Our HOA fees.

Our actual child.

“Okay,” I said quietly. “Thank you for telling me exactly what happened.”

Inside, I was furious.

From a professional standpoint, what she did—singling out a nine-year-old waiting at a bus stop and implying he was some sort of threat for wearing a hoodie—was unacceptable.

From a personal standpoint, I wanted to go down there and give her a detailed presentation on how not to speak to children that didn’t belong to her.

Instead, I took a breath and thought like a chief.

“Let me see the camera,” I said.

We have a Ring camera that catches part of the sidewalk where the kids gather.

While Eli ate the rest of his breakfast, I rewound the footage.

There she was.

Clipboard in hand, cardigan perfectly folded on her shoulders, standing about two feet from my kid, finger pointing at his face.

Even without sound, the body language said everything: sharp gestures, Eli shrinking back, another kid shifting uncomfortably.

I could pull the audio from the cloud later if I needed it.

For now, I got the gist.

I walked Eli back to the bus stop myself.

By then, the bus was turning onto our street. The woman—Marjorie, I saw now on her mailbox—was nowhere in sight.

“Are you mad?” Eli asked quietly as the bus rolled up.

“I’m not mad at you,” I said firmly. “You did the right thing coming home to tell me. I’m upset with an adult who forgot how to act like one.”

He looked relieved.

“Should I not wear hoodies anymore?” he asked. “I don’t want to get in trouble.”

That one question made my intact heart crack just enough to let in some serious determination.

“You wear whatever keeps you warm and follows the school rules,” I said. “If anyone has a problem with that, they can talk to me.”

He nodded and climbed on the bus.

I waved to the driver, who waved back like she knew something had happened.

She probably did.

The kids talk.

The adults rarely listen.

3. The Email, the Rule, and the Spark

I decided not to escalate it immediately.

My first step was always information.

That afternoon, I pulled up the HOA website (yes, of course they had one) and found the board contact page.

There it was:

President: Marjorie L. Whitfield.

Of course she was the president.

I drafted a polite email:

Hi Marjorie,

My name is Chief Rebecca Cole. My family recently moved into [address]. This morning, there was an interaction at the bus stop between you and my son, Eli. He came home very upset after being told he looked “suspicious” for wearing his hoodie up while waiting for the bus.

I’d like to clarify if there is any HOA rule regarding the bus stop area and children’s attire, or if this was a misunderstanding. As both a parent and our city’s police chief, I’m concerned about any adult addressing young children in a way that makes them feel unsafe in their own neighborhood.

I’d appreciate it if we could discuss this.

Best,

Rebecca

I reread it to make sure there was no sarcasm leaking out.

Then I hit send.

She replied twenty minutes later.

Rebecca,

Thank you for reaching out. I did speak with a group of children at the bus stop this morning. We have had ongoing issues with unsupervised minors damaging the landscaping and loitering before and after bus pick-up. As HOA president, it is my responsibility to maintain a safe and orderly neighborhood environment.

There is no specific dress code, but it is common sense that children should not cover their faces, as this can be alarming to residents and make it difficult to identify who is on the property. I simply reminded your son of this. If he felt “unsafe,” that was certainly not my intention.

We encourage parents to accompany young children to the bus stop to prevent further issues.

Respectfully,

Marjorie L. Whitfield

President, [Neighborhood] HOA

I stared at the email.

Covered their faces? He had a standard cotton hoodie with the hood halfway up. His face was completely visible. This wasn’t a mask or anything like that.

Also, “loitering at their own bus stop” was a new one.

I typed a response, deleted it, typed again, deleted again.

I’m human. The first draft was not something a chief should send.

I finally settled on:

Marjorie,

Thank you for the clarification. I understand the desire to prevent damage to the common areas, and I fully support kids treating the neighborhood respectfully.

That said, I’ve reviewed our home security footage from this morning. The interaction appeared more confrontational than a simple reminder. I’d be happy to discuss reasonable guidelines for bus stop behavior at the next HOA meeting, but I must respectfully insist that concerns about my child be brought to me directly, rather than through confrontations that leave him feeling threatened.

Please let me know when the next meeting is scheduled.

Chief Rebecca Cole

She didn’t respond.

Fine.

We’d handle it live.

4. Second Strike: When the Argument Turned Serious

I wish I could say things cooled off.

Instead, two days later, Marjorie escalated.

It was Thursday. I was working a later shift, so I planned to walk Eli to the bus stop and just quietly exist as a deterrent.

I figured my presence would be enough.

We barely made it halfway down the block before I heard her signature tone—polite on the surface, sharp underneath.

“There he is,” she said, stepping off her front lawn with that clipboard like it was a badge. “The little one with the drawings.”

Drawings?

Eli stiffened.

“Good morning,” I said calmly. “We’re just heading to the bus stop.”

“Yes, well, we need to talk,” she said, planting herself directly in our path. “Your son has been writing on the HOA bulletin board.”

I blinked.

“The… what?” I asked.

“The bulletin board,” she repeated. “Someone has been drawing on the bottom strip with a marker. Little faces, rocket ships, stars. It’s inappropriate for community property.”

I looked over her shoulder.

The bulletin board by the bus stop did indeed have a few small doodles at the very bottom of the wooden frame. They were actually pretty good—little cartoon rockets and a smiling heart. They were also done in dry-erase marker, and could be wiped off with one swipe.

“It’s just drawings,” Eli said quietly. “Everyone thought they were funny.”

“You admitted it,” she said sharply.

“He didn’t admit anything,” I cut in. “He made a general comment. Do you have proof he’s the one drawing on the board?”

“The other children said it was him,” she replied. “And when I asked him yesterday, he looked guilty. Besides, we have rules about defacing community property.”

The bus hadn’t arrived yet. A few other kids and parents were already gathered, watching this unfold.

“You questioned him without me present?” I asked, keeping my tone level.

“I asked a perfectly reasonable question,” she said. “Which he refused to answer. That is suspicious behavior. I told him if he continued, I would have him banned from the bus stop area—”

“You can’t do that,” I said. My voice was still quiet, but the heat underneath it had risen a few degrees.

“As HOA president,” she said, “I can restrict access to common areas for residents who continually disregard community standards.”

My eyebrows went up.

“Residents,” I repeated. “He is nine. And waiting for the bus where the school district told him to wait.”

“Then maybe his parents should teach him respect for property,” she shot back. “Maybe his parents shouldn’t let him wear clothes that make him look like he’s up to no good. There are other neighborhoods where that behavior is acceptable. Not here.”

There it was.

The thin line between “rules” and thinly coded judgment.

I felt the eyes of the other parents on me.

The argument had officially become serious.

“Okay,” I said, taking a step forward. “We are going to stop right there.”

“Excuse me?” she said.

“You will not talk about my child’s clothing,” I said. “You will not threaten to ‘ban’ him from a public school bus stop. And you absolutely will not imply that kids who doodle rocket ships are some kind of threat to the community.”

She blinked, startled by the pushback.

“You have no authority to—” she began.

“I have plenty of authority,” I said. “Some of it as his mother. Some of it as the person you sent that email to the other day. And some of it as the current chief of police in this city.”

That last part I dropped as calmly as if I’d said I was the mail carrier.

It landed like a small explosion.

5. “I’ll Call the Police!” / “I Am the Police.”

Her mouth opened.

Closed.

“You’re what?” she said, the color draining slightly from her face.

“Chief Rebecca Cole,” I said. “My office is ten minutes away. I’ve spent my entire career working with communities on how to make neighborhoods safer for children, not more intimidating.”

A gasp rippled through the small crowd of parents.

One dad muttered, “Oh, wow,” under his breath, like this was suddenly much more interesting than his coffee.

“If you’re law enforcement,” she said stiffly, “all the more reason you should understand we can’t have unsupervised children damaging property and making residents uncomfortable.”

I took another breath.

We were at a fork in the road. I could pull rank, quote statutes, and shut this down purely from a power standpoint.

Or I could treat this like every other neighborhood dispute I’ve ever mediated and walk us back from the edge.

I opted for a balanced approach.

“Let’s clarify a few things,” I said. “One: this is not criminal damage. That is a dry-erase marker on a reusable board. It wipes off. Two: you have no authority to threaten a child with removal from a public bus stop. Three: if you have a concern about a minor, you should speak to their parent, not interrogate and intimidate them.”

She bristled.

“I did email you—”

“After confronting him once already,” I interrupted. “Today makes twice. That’s a pattern.”

Her posture went even straighter.

“I have a duty to this community,” she said. “People rely on me to keep our standards high. Children drawing on signs and loitering around in clothing that covers their faces—”

“They are literally waiting for the school bus,” another mom cut in. “With backpacks. At seven thirty in the morning.”

Marjorie blinked, apparently surprised anyone else was chiming in.

“I’m not comfortable with this behavior,” she insisted.

“Then you should bring it to the HOA board or to the parents,” I said. “Not take it out on kids. Right now, what you’re doing is bordering on harassment.”

Her eyes flashed.

“That’s a serious accusation,” she said.

“I’m using the plain-language meaning,” I replied. “Adult repeatedly targeting minor with confrontational comments and threats? That’s what most people would call it.”

“I could call the police about the vandalism,” she snapped.

There it was.

The old card.

“I could file a report—”

“I’d be happy to take that report,” I said. “Here.”

I pulled my badge out of my jacket pocket and held it up.

The silence was immediate.

Even the kids stopped fidgeting.

I didn’t flash it like some dramatic television hero. I just held it, steady, at chest height.

“You wanted the police,” I said quietly. “You’ve got the highest-ranking one in the city standing right in front of you, telling you that this is not the way to handle your concerns.”

Her eyes flicked from the badge to my face.

Then to Eli, who was watching wide-eyed.

Her shoulders sagged just a little.

“Oh,” she said faintly.

A younger man I’d seen jogging on the street sometimes stepped closer.

“With all due respect, Marjorie,” he said, “I’ve seen the ‘vandalism.’ It’s a couple smiley faces. My daughter thought the HOA did it to make the board look more fun.”

A ripple of laughter spread through the group.

Even a few kids giggled.

This wasn’t a mob. Nobody shouted. Nobody got in her face. But the spell she’d cast over the bus stop—for herself, as the self-appointed enforcer—was breaking.

“We all want the kids to be safe,” I said. “If there are real issues—fighting, bullying, dangerous behavior—then yes, adults should step in. But hoodies are not crimes. Dry-erase doodles are not emergencies. Children waiting for a bus are not intruders.”

She looked around like she was seeing the group for the first time, really seeing them.

It’s amazing how quickly a dynamic flips when the crowd doesn’t silently back the authority figure.

“I was only trying to uphold the rules,” she said, voice smaller now.

“Then let’s talk about the rules in the right setting,” I said. “At the HOA meeting. With input from actual parents. And maybe from the kids too, since they’re the ones standing here every morning.”

The bus’s familiar rumble echoed down the street, giving us a convenient pause.

“Eli, go ahead,” I said gently. “I’ll stay here.”

He hesitated.

“Are you sure?” he whispered.

“I promise,” I said. “You’re okay.”

He nodded, gave me a quick hug, and climbed on the bus.

As it pulled away, I turned back to Marjorie.

“We’ll talk later,” I said. “For now, please do not approach my child directly again. If you need to reach me, you know how.”

She didn’t argue.

She just turned and walked stiffly back to her house.

The other parents lingered for a second.

A couple of them came over to me.

“Thank you,” one mom said. “She’s been… intense with the kids for a while. We didn’t know how to address it.”

“Yeah,” the jogging dad said. “Figured we’d mind our own business. But seeing her point at your kid’s face like that—”

He shook his head.

“Sometimes,” I said, “it only takes one person saying, ‘Actually, this isn’t okay’ for everyone else to realize they were uncomfortable too.”

I’ve seen that play out in a lot of contexts.

Apparently, HOA bus stops are one of them.

6. The Fallout: HOA Meeting from a Different Angle

You’d think the story ends there.

It doesn’t.

Remember that email asking about the next HOA meeting?

It was scheduled for that following Tuesday.

I showed up.

Not in uniform. Not with a stack of legal codes. Just in jeans and a sweater, with my husband and a still slightly cautious Eli at home.

The meeting was in the community clubhouse. Folding chairs, long table, pitchers of water. A whiteboard with “AGENDA” written at the top like it was a middle school classroom.

There were maybe twenty residents there.

Marjorie sat at the center of the table, gavel in front of her like she was chairing a city council instead of an HOA.

She cleared her throat.

“Next order of business,” she said after we’d painfully slogged through landscaping updates. “We have a resident who requested time to speak about the bus stop. Chief Cole?”

Every head turned toward me.

I stood.

“Thank you,” I said. “I appreciate the chance to talk about this openly.”

I kept my tone neutral.

I briefly described what had happened:

The hoodie comment.

The “covering faces” language.

The doodle accusation.

The threats about banning a nine-year-old from a bus stop.

I didn’t use the word “Karen.” I didn’t mock her. I didn’t raise my voice.

I just laid out the facts.

You know what happened?

Other people backed me up.

Someone said, “Yeah, my son came home nervous after she told him he ‘didn’t belong’ on the common lawn if he wasn’t in dress clothes.”

Someone else added, “She told my daughter she couldn’t sit on the bench because her backpack might ‘scuff the paint.’ It’s a metal bench.”

Another resident said, “Last month she threatened to fine us because our holiday decorations weren’t ‘in line with the neighborhood’s seasonal theme.’”

The room filled with examples.

Nothing criminal.

But enough little overreaches to paint a clear picture.

Marjorie’s face went from pink to pale.

“I have been trying to maintain standards,” she said.

“And we appreciate your effort,” I said. “Community standards are important. But so is how we treat each other. Standards shouldn’t make nine-year-olds scared to wait for the bus.”

An older gentleman at the end of the table—the treasurer, according to his name tag—cleared his throat.

“Maybe we’ve given the presidency too much practical power,” he said. “It might be time to review how we handle enforcement. And how we interact with children.”

“What do you suggest?” another board member asked.

He looked at me.

“If the chief is willing,” he said, “maybe she can help us draft some guidelines. Something reasonable. Focused on actual safety, not just appearances.”

All eyes swung back to me.

I held up my hands.

“I’m happy to help,” I said. “On one condition: whatever we write, we do with input from the people it affects. That means parents, yes. But also the kids who wait at that stop every day. You’d be amazed what they see that adults miss.”

A low murmur of agreement spread.

One of the board members, a quiet woman who’d barely spoken, leaned toward the mic.

“I also move,” she said, “that we create a simple complaint process. If residents feel an HOA official is overstepping, they should have a clear way to report that, and we should have a clear way to review it.”

It was politely worded, but everyone knew what she meant.

This wasn’t a public trial.

No one shouted “You’re fired.”

But the message was clear:

Things were going to change.

They took a vote to form a small committee to review bus stop policies and interaction guidelines.

I got “volunteered” to chair it.

I agreed, because if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that monsters grow in unclear policies and unchecked authority—whether in a police department or a cul-de-sac.

When the meeting ended, people trickled out in pairs and small groups.

Several stopped to talk to me.

“Honestly,” one dad said, “I was worried you might use your position to really hammer her. But that was… fair.”

“I don’t want anyone afraid to live here,” I said. “That includes her. But my first job is to make sure kids feel safe.”

As I walked to my car, I noticed Marjorie standing near the door, gathering her papers slowly.

She looked smaller without the table and gavel in front of her.

“Chief Cole,” she said as I approached.

“Rebecca is fine,” I replied.

She swallowed.

“I… may have been a little too firm,” she said. “With the children.”

“A little,” I agreed gently. “I get it. You care about this place. You want it to look nice, feel safe. That’s not a bad instinct. It just came out sideways.”

She focused on her stack of papers.

“I lost my husband last year,” she said suddenly. “We used to walk this neighborhood together. We planted some of those shrubs by the bus stop ourselves. When I see kids cutting through them, I feel like… like they’re stepping on the last project we did together.”

The admission caught me off guard.

I’d been ready to hear excuses.

I hadn’t been ready to hear grief.

“I’m sorry,” I said quietly. “I didn’t know.”

“I shouldn’t have taken it out on them,” she said. “I see that now. I just… I don’t like change. And the world has been changing so fast.”

“Believe me,” I said, “I spend most of my days trying to catch up with it.”

I paused.

“Maybe instead of seeing the kids as the people ruining what you built,” I said, “you can start seeing them as the next people who’ll care about it. If we invite them into the process instead of pushing them away, they might actually protect those shrubs for you.”

She gave a small, surprised laugh.

“I hadn’t thought of it like that,” she said.

“Give it a try,” I suggested. “The committee will need more voices than just mine. I promise not to yell. Much.”

Her mouth twitched.

“Deal,” she said softly.

7. What Changed After That

A few weeks later, the bus stop looked different.

Not physically. Same bench, same bulletin board, same patch of grass.

But the mood had shifted.

We held one short, informal “meeting” right after school where we asked the kids for their ideas.

We bought them pizza. They love pizza.

We said:

“What makes you feel safe at the bus stop? What makes you feel uncomfortable? What do you wish the adults here would do differently?”

They said:

They liked when grown-ups were nearby but not standing right on top of them.

They didn’t like being yelled at for small things like leaning on the fence.

They wanted a trash can closer by so nobody tossed snack wrappers on the ground.

They liked the drawings on the bulletin board and promised to only use dry-erase markers.

They thought it would be fun to have a “bus stop captain” rota to remind everyone to pick up their trash and not run into the street.

The kids came up with that.

Not the adults.

We put together a one-page guideline:

No running into roads.

No climbing trees or fences.

No roughhousing that could hurt someone.

Drawings only on the designated corner of the board, dry-erase only.

Respect other people’s space and stuff.

Simple.

Not a single hoodie restriction in sight.

We shared it with the HOA and the school.

Parents started taking turns being the “bus stop adult”—not to police the kids, but to be a friendly presence.

Sometimes that adult was me.

Sometimes it was Marjorie.

The first morning she came out after the whole incident, I watched her carefully.

She brought a small bag with wipes and a little container of dry-erase markers.

“Good morning,” she said to the kids. “I, um, brought markers for the drawing corner. If anyone wants to make one that fits the season, we can leave it up for the week.”

The kids eyed her like she was a new transfer student.

Then one brave kid said, “Can I draw a snowman when it’s winter?”

“Yes,” she said. “That would be wonderful.”

They warmed up to her faster than the adults did.

Kids are often more forgiving than we deserve.

That afternoon, Eli came home with a story.

“Ms. Whitfield asked me what my favorite superhero was,” he said, kicking his shoes off. “I said I like astronauts better. She said her husband liked them too. We’re going to draw a rocket ship together next week.”

I smiled.

“Does that make you feel better about the bus stop?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “I don’t think she’s mad at us anymore. I think she was just… sad.”

I nodded.

“Sometimes grown-ups act weird when they’re sad,” I said. “The important part is what they do when they realize they hurt someone.”

8. Why I Wrote This Down

I know the internet loves a clean “then she got what was coming to her” story.

And sure, there were consequences:

The HOA board put checks in place so one person couldn’t throw their weight around unchecked.

There’s now a complaint process.

The wording on the rules is less about “appearances” and more about actual safety.

But the ending wasn’t a dramatic takedown.

No one got arrested.

No one got publicly shamed.

What really happened was this:

A woman who’d been using rules as a shield to manage her own anxiety got called out, firmly but fairly, and chose to adjust instead of doubling down.

A group of parents realized they’d been ignoring their own discomfort because confronting someone is hard.

A police chief remembered that her job isn’t just about responding to emergencies, but also about modeling how to handle conflict without turning it into a power contest.

And a nine-year-old learned that when an adult treats you unfairly, you can tell your parents, and they’ll actually do something about it instead of saying, “Just ignore it.”

That last part matters the most to me.

To this day, if you drive past our little bus stop, you’ll see:

A group of kids in hoodies and jackets and mismatched backpacks.

A bulletin board with a small drawing in the corner—usually a rocket, or a smiling sun, or a snowman with a crooked hat.

An older woman in a pastel sweater asking them about their day, reminding them to look both ways, and occasionally telling a story about the time she and her husband got lost on a road trip and ended up at a space museum by accident.

And somewhere, a police chief who once had to say, “You wanted to call the police? I am the police,” drinks her coffee and feels oddly grateful that an HOA argument at a bus stop turned into a lesson on how communities can actually grow up a little.

Even the “Karens.”

Maybe especially them.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

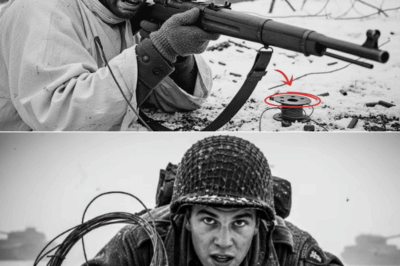

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load