From Shock in the Rail Yards to Awe in the Skies: How German Prisoners of War Discovered the Relentless Industrial Heartbeat That Powered America’s March Across the Battlefields of World War II

When the train doors finally cracked open, the German prisoners were ready for anything.

They had imagined angry crowds with stones and insults. They had imagined endless fields of corn and dusty roads, a countryside too far away from the war to matter. Some imagined nothing at all, empty from weeks of captivity and the long voyage across the Atlantic.

What they did not imagine was a sky lit up like daylight at midnight.

Leutnant Karl Reinhardt stepped down from the car and froze on the wooden platform. The air was cool, but the horizon glowed in a strange orange haze. Beyond the trees, smokestacks painted dark silhouettes against the night. Somewhere far off, a whistle wailed, and then another, until the sound became a kind of metallic choir.

It was the first time Karl understood that every rumor he’d heard about America’s factories might be true.

The Long Journey West

Karl had been captured in Italy in late 1943. His unit, once proud of its discipline and training, had been ground down by shortages and exhaustion. When the surrender order came, it felt less like defeat and more like an exhale that had been held too long.

He and hundreds of other prisoners were taken to a port, placed on a ship, and told they were heading to a camp in North Africa. A week later, when the coastline that appeared was not desert but a wide green shore with tall cities and smoking chimneys, the guards finally told them the truth.

“You’re in the United States now,” a sergeant said, almost casually. “You’ll be well fed, if you behave.”

For many of the prisoners, the name alone felt unreal. The United States was something they had seen on maps and in propaganda pamphlets—distant, vague, full of jazz and skyscrapers and the promise of endless resources. Now they were standing on its soil, surrounded by military police, wondering what kind of empire had the luxury to ship its enemies halfway around the world simply to store them safely.

From the harbor, they were herded onto trains. Days passed as they moved inland, through landscapes Karl had only ever imagined—endless fields, small towns with white churches, wide rivers with bridges that seemed to float forever. Every time the train slowed near a crossing or a station, he heard the same thing: the rumble of industry.

Engines. Tractors. Trucks. Whistles. A constant hum.

He tried not to show his unease, but it grew with every mile.

First Glimpse of the Arsenal

The POW camp was on the outskirts of a Midwestern town whose name Karl didn’t catch the first few times it was spoken. What he did catch, unmistakably, was the scale of what lay nearby.

The camp itself was typical—barbed wire, guard towers, barracks built of wood and tar paper. But just beyond the wire, in the distance, stood row after row of buildings that dwarfed everything else. Their roofs were flat, their sides steel and brick, their windows long and repeating. At night, they glowed.

“Factory,” someone whispered beside him as they lined up for their first roll call.

“Factories,” corrected another prisoner, an older sergeant who had worked in industry before the war. “Plural. You can tell by the stacks.”

Karl followed his gaze. There weren’t just a few smokestacks. There were dozens, stretching across the horizon like a forest of dark needles.

He had seen industrial centers back home—steel plants, rail depots, chemical works. But they had always felt precarious, strained by shortages and air raids, surrounded by blackout curtains and sandbags. The American complex across from the camp felt different. It pulsed with light and motion, as if the war were an opportunity rather than a burden.

That night, as he lay on his bunk, the hum of distant machinery drifted through the thin walls. It was steady, almost soothing. Almost.

“It doesn’t stop,” murmured Dieter, the young radio operator in the bunk above him. “How can it not stop?”

Karl didn’t answer. He was wondering the same thing.

Work Detail

A week later, the camp commander addressed the prisoners on the parade ground. Through an interpreter, he explained the rules: they would be treated according to international conventions, they would receive adequate food and shelter, and they would have the opportunity to work.

“Work is voluntary,” the interpreter said, his voice carrying across the neat rows of uniforms that had long since lost their crispness. “You will be compensated with canteen credits. You will not be required to work in tasks directly tied to combat. Most of you will be assigned to farms, lumber camps, or support jobs.”

The word farms actually sounded appealing. Many of the younger soldiers had grown up in the countryside. Working with soil, even enemy soil, seemed comforting.

Then came the surprise.

“Some of you,” the interpreter continued, “will be assigned to nearby manufacturing plants. You will not handle weapons directly, but you may be involved in general production and maintenance. These tasks will be closely supervised.”

A murmur spread through the ranks. Factories? Here?

Karl, with his background in engineering before the war, knew instantly that he would be on that list. He wasn’t wrong.

Two days later, he found himself in the back of a guarded truck with two dozen other prisoners, bouncing down a paved road toward the complex they had only seen from a distance.

The Assembly Line That Never Slept

The closer they came, the larger everything seemed.

They passed a rail yard where lines of freight cars stretched farther than Karl’s eyes could follow. Cranes moved overhead, lifting crated engines, barrels, and metal beams as easily as a child arranging toys. Locomotives rolled in and out, snorting steam like iron beasts.

“That’s just the yard,” one American guard said, catching the German officer’s gaze. “Wait till you see the plant.”

The guard wasn’t boasting. When the truck turned past a security checkpoint and entered the main complex, the prisoners fell silent.

The building they approached was massive, easily the size of several city blocks. Its wide doors were open, and the sound pouring out hit them like a wave—clanging, whirring, shouting, the high hiss of compressed air and the low growl of conveyors in motion.

Inside, the world became movement.

Rows of workstations stretched into the distance, each one specializing in a single task. Men and women in overalls stood at benches, guiding metal parts down the line. Overhead cranes slid back and forth, carrying engines that looked like caged thunder. Tools hung from retractable cords. Conveyor belts moved at steady, relentless speeds.

“Eyes forward,” a guard ordered, but it hardly mattered. There was something hypnotic about the rhythm.

Karl’s group was guided to the edge of one of the production areas. A supervisor in a clean, pressed shirt met them. He spoke to the military escort in English, then turned to the prisoners.

“I’m Mr. Hawkins,” he said, using a formal, almost schoolteacher tone. “You’ll be assisting with non-critical tasks—moving crates, cleaning, keeping parts sorted. You’ll be trained. You’ll work under supervision. You follow instructions, we have no problems.”

He paused, studying their faces. To Karl, he looked less like a boss and more like an engineer—eyes always measuring, mind always calculating.

“You’re guests of the United States,” Hawkins went on. “You do your jobs, you get your breaks and your meals. Cause trouble, and you go back to the camp. Understood?”

The interpreter repeated his words in German. The prisoners nodded.

As they were handed work gloves and simple identification tags, Karl couldn’t stop watching the line. An engine block arrived at a station bare and raw; a few minutes and a dozen pairs of hands later, it moved on with valves, fittings, and components attached. A few stations later, another team added wiring, hoses, and covers.

It struck him that the people working each station didn’t need to know everything about the engine. They just needed to know their task perfectly. The line itself held the knowledge of the whole.

He had seen assembly lines before the war. But not like this. Not at this scale. Not with this calm, confident efficiency.

Numbers That Didn’t Add Up

During their first lunch break in the factory cafeteria, the POWs sat at separate tables under watchful eyes. The food was simple but decent—sandwiches, soup, coffee in thick white mugs. On the walls were posters showing charts, goals, and slogans: “More Output, Sooner Victory.” “Every Hour Counts.”

Karl studied one chart more closely. It showed a rising curve of production numbers—tanks, trucks, aircraft, ships. The figures seemed almost absurd.

“These are exaggerations,” muttered Dieter, who sat across from him. “They must be.”

“They might not be,” replied the older sergeant, whose name was Müller. “Have you seen how many people are in this plant alone?”

Karl had. He estimated thousands, all moving with a purposeful energy that didn’t feel forced by fear. There were women, older men, young workers barely out of school, all sharing the same space. They joked, shouted across the noise, and wiped sweat from their faces without complaint.

In Germany, workers had become accustomed to rationing, blackouts, sirens, and shortages. Here, the lines moved as if nothing in the world could disrupt them.

“How many plants like this do you think they have?” Karl asked quietly.

No one answered. The question hung in the air, heavy and unspoken.

The Night Shift Revelation

A few weeks later, Karl was assigned to a night shift. He dreaded it at first, expecting the fatigue and monotony to wear him down. Instead, he came back to the barracks at dawn with a new kind of unease.

The factory at night was almost more impressive than during the day.

Outside, the sky turned deep navy blue, and the stars emerged. But inside the plant, it might as well have been noon. Bright lamps burned overhead. The hum of machinery never lowered. The same assembly lines, the same conveyors, the same flow of parts and products continued without pause.

On a short break, Karl stepped outside under the supervision of a guard and looked across the complex. Other buildings were just as alive, their windows glowing. In the distance, another plant’s roof shimmered under floodlights.

“You don’t stop?” he asked the guard in halting English.

The man shrugged. “War doesn’t stop,” he replied. “Why should we?”

Karl understood the meaning, but that wasn’t what truly unsettled him. What unsettled him was that the worker he had seen just moments before—an older woman with lines on her face—had laughed at a joke from her coworker, even as she labored through the night.

Morale, he realized. They still have morale.

He thought of his last months in Europe—the haggard faces, the anxious glances at the sky, the constant talk of shortages. Factories back home had pushed hard, yes, but they had pushed against the weight of scarcity. Here, the push felt different, as though the effort were supported by an endless foundation of resources.

He imagined similar plants scattered across the continent, all humming day and night. He imagined ships coming and going from ports he had never heard of, trains racing across mountains and deserts, all feeding the same vast machine.

For the first time, the war stopped feeling like a contest and started feeling like a mathematical equation. Numbers. Scale. Volume.

And the numbers here didn’t add up in Germany’s favor.

Conversations Across the Wire

Back at the camp, life settled into a routine. There were roll calls, inspections, letters from home that came late and carried old news, games of soccer in the yard, and quiet evenings where men sat on their bunks staring at nothing, lost in thought.

One afternoon, while waiting in line at the camp canteen, Karl overheard two fellow prisoners arguing about what they had seen in their respective work assignments.

“They’re overwhelmed,” insisted a man who worked at a nearby farm. “They have fields for miles. They need us just to get the crops in. Their young men are gone, same as ours.”

“That doesn’t matter,” countered another, who worked at the rail yard. “Do you know how many trains run through there every day? Dozens. Maybe more. And that’s just one yard. It’s like their entire country is a supply line.”

Karl felt compelled to speak up.

“You’re both right,” he said. “They have shortages of hands in some places, but not of material. Not of energy. You should see the factory where we work. It never stops. And the workers—they’re tired, but they’re not broken.”

The two men looked at him with a mix of skepticism and curiosity.

“So what are you saying?” the farm worker asked.

“I’m saying,” Karl replied slowly, choosing his words, “that our leaders told us this war would be decided by spirit, discipline, and strategy. Those things matter, yes. But here, they’ve added something else.”

“And what’s that?” the rail-yard prisoner asked.

“Capacity,” Karl said. “They simply have more of everything. And they know how to use it.”

The words left a bitter, metallic taste in his mouth. Saying them out loud felt like a kind of betrayal, not of his country exactly, but of the certainty he’d carried into the war.

The Day the Trainees Arrived

One late spring morning, the factory hosted a group of visitors—new American soldiers, still in training, who had been brought to see where their equipment came from. They walked in lines through the aisles, helmets under their arms, their eyes wide as they watched engines and parts move down the line.

At his station sweeping metal shavings, Karl noticed a young private stop to stare at a nearly complete vehicle chassis. The private’s expression held a mix of pride and apprehension, as though he were seeing his future in steel.

The supervisor, Mr. Hawkins, paused beside him.

“Every bolt you see,” Hawkins told the soldier, “was made by someone who wants you to come home safe. Don’t forget that when you’re out there.”

The private nodded. His eyes flicked briefly toward Karl and the other POWs. For a second, their gazes met. The young American didn’t look angry or hateful—just thoughtful, maybe even curious.

Later, during a break, Dieter leaned against the wall beside Karl.

“Did you hear what he said to that soldier?” Dieter asked. “The one about everyone wanting him to come home?”

Karl nodded.

“Back home, they told us we were fighting for survival,” Dieter continued, his voice low. “Here, they talk about coming home. Do you know what that means?”

“It means they expect to win,” Karl said, but Dieter shook his head.

“It’s more than that. It means they can imagine a world after this war. I haven’t done that in a long time.”

Karl had no answer. He wasn’t sure he’d been able to imagine life after the war, either—not clearly. Everything had been about the next battle, the next line on the map. Here, in the glow of the factory lights, the Americans seemed to be planning for a future where all this machinery would build cars, tractors, and appliances instead of tanks and guns.

The war, to them, was a brutal detour—not the whole road.

Letters From Home

Months passed. Seasons began to blend together, marked not by holidays or celebrations but by changes in the air and the type of work assigned.

In late 1944, a letter reached Karl from his younger sister, Anna, still living in their hometown. He read it slowly, savoring every line. She spoke of ration cards, of long lines for basic goods, of nights spent in bomb shelters listening to distant thunder that wasn’t weather. She wrote that factories nearby had been hit, that production had slowed, and that many friends had been evacuated or conscripted.

We still believe in you, she wrote. We still hope for good news.

Karl folded the letter carefully and stared at it for a long time. Around him, the barracks hummed with the low murmur of other men reading their own letters—some smiling faintly, others silently wiping away tears.

He thought of what he had seen that very morning: a new assembly line being installed next to the old one. The plant was expanding, not shrinking. New workers were arriving, some in civilian clothes, some in uniforms with the patches of specialized corps—engineers, logistics officers, technicians.

Even as his homeland strained under bombardment, the industrial world around him in America was growing more complex, more efficient.

That night, lying awake, Karl realized something that made his chest tighten. His sister’s hope was built on an image of their country’s strength that no longer matched reality. Here, in this camp and this factory, he could see the other side of the scale.

And the scale was tipping.

A Quiet Admission

In early 1945, after a long shift, Mr. Hawkins approached Karl directly as he was returning tools to a rack. The supervisor had learned a few German phrases by then, enough to exchange simple words without the interpreter.

“You do good work,” Hawkins said in careful German.

“Thank you,” Karl replied in equally careful English.

Hawkins glanced around to make sure the guards were close enough to keep things official but far enough not to intrude.

“You were engineer before war, yes?” he asked.

“Yes,” Karl answered. “Automotive design.”

Hawkins nodded as though confirming something he had suspected.

“What do you think?” he asked, gesturing broadly to the plant. “Honest answer.”

Karl hesitated. Honesty, in wartime, was rarely a simple thing. But he was tired, and the question had been hovering over him for months.

“It is…impressive,” he said finally. “Efficient. Large. Very large.”

Hawkins smiled faintly.

“We built some of this after you got here, you know,” he said. “Plans were on the shelf. Once the war started, we just took them down and got to work.”

That casual remark struck Karl almost as hard as the first glimpse of the glowing factories months earlier.

On the shelf, he thought. They had the plans already, waiting. As if they had anticipated a need for more, or simply believed that growth was inevitable.

Hawkins studied him for another moment.

“I’ll tell you something, Lieutenant,” he said, his voice dropping slightly. “When I was your age, we had a depression here. Hard times. People out of work. Factories quiet. We learned then that when things are still, you have a choice. You can give up, or you can build something better.”

He shrugged.

“Now we’re building. That’s all this is. Building faster than the other side can break.”

Karl could have argued, could have pointed out that what they were building were engines of destruction as well as hope. But he didn’t. Because beneath the steel and smoke, he recognized a mindset he had only partly understood before—a belief in capacity, in problem-solving, in scale.

The realization was painful, but it was clear: America had turned its culture of invention and industry into a weapon as powerful as any artillery piece.

The News No One Could Ignore

As winter turned to spring, rumors filtered into the camp. Some came from guards who let slip a headline or two; others came from news bulletins posted in common areas. The front lines were shifting. Cities that had seemed distant and untouchable were being surrounded. Allies were pushing from multiple directions.

One evening, the camp loudspeakers crackled to life. The commandant’s voice, solemn and measured, announced that an important message would be shared. The prisoners gathered around the central yard, standing shoulder to shoulder as the wind tugged at their jackets.

Through an interpreter, they heard the news: major advances, collapses of defenses, and the unmistakable sense that the war in Europe was nearing its end.

No cheers rose from the men in the yard. There were no celebrations. Just a deep, collective exhale—somewhere between relief and grief.

Back in the barracks, discussions turned late and intense.

“So it’s true,” said Müller, the older sergeant. “We fought with everything we had. But we never had what they have.”

He didn’t need to specify who they were. Everyone knew.

Karl sat on the edge of his bunk, staring at his hands. Months of labor had toughened them again. He thought of the endless lines of machines, of the rail yards, of the night shifts that felt like days. He thought of the charts on the cafeteria walls, curves rising even as his homeland’s lines were being bombed into dust.

“Do you remember what they told us before the war?” Dieter asked, his voice quiet but steady. “That other nations were soft, distracted by comfort, too dependent on luxury to endure real hardship?”

“I remember,” Karl said.

He remembered lectures about decadence, about how industrial nations could be toppled by determined will. And yet here, in this place built on assembly lines and logistics, he had seen a different kind of strength—one that combined comfort with discipline, abundance with organization.

“They weren’t soft,” he said at last. “They were prepared.”

A Train Full of Proof

Not long after the announcements about the changing front lines, Karl’s work detail was temporarily transferred from the factory floor to the rail yard. His task was simple: help unload cargo from arriving trains and sort it into designated areas.

He expected crates of parts, machinery, maybe food. He did not expect what actually came.

One long train after another rolled in, each carrying a different piece of the puzzle. Some wagons were filled with raw materials—steel, copper, rubber. Others held finished machines ready to be shipped to ports and loading docks. Still others—this was what truly stunned him—were filled with brand-new equipment destined not for the current war, but for training and postwar projects.

“Why are they still making so much?” Dieter wondered aloud as they wrestled a crate onto a dolly. “The war is nearly over.”

“Maybe they don’t know when it will end,” Karl replied.

But privately, he suspected something else. They were not only equipping armies; they were building a future. They were already preparing to turn wartime production into peacetime prosperity.

As another train rolled in, Karl noticed something that made him stop in his tracks. Painted on the side of a large crate were the words: “Machinery—For Reconstruction Efforts.”

Reconstruction. The word hit him like a shock.

Where others saw ruins, these people were already planning rebuilding. Even before the guns went silent, they were shipping out tools to mend what had been broken.

In that moment, staring at the simple black letters on the wooden crate, Karl felt the last illusion of parity slip away. This was not just a powerful country fighting a war. This was a country that had built an industrial engine capable of reshaping the world after the war ended.

Quiet Respect

When the war in Europe finally ended, the announcement at the camp was brief but unmistakable. The guards stood with their shoulders a little looser. Some of them allowed themselves quiet smiles. The prisoners reacted in many ways—some with tears, some with stunned silence, some with anger that had nowhere to go.

Over the weeks that followed, work in the factories slowly shifted. Some lines wound down; others were retooled for civilian production. Posters about wartime output were replaced with notices about returning workers, reemployment programs, and the challenges of peace.

One day, as Karl’s group returned from a final shift at the plant, Mr. Hawkins met them near the loading dock.

“The war in Europe is over,” he said, speaking slowly in English, though most of them understood the words now. “You’ll be going home eventually. There’s a lot to figure out first, but it will happen.”

He paused, as if searching for the right tone.

“I don’t expect you to feel gratitude,” he continued. “You’re soldiers, and you fought for your country. But I hope that when you go back, you remember that you were treated fairly here. And that you saw something worth learning from.”

Karl stepped forward slightly.

“I will remember,” he said. “I saw your factories. Your trains. Your…organization.” He hesitated, then added, “It is…impossible to ignore.”

Hawkins inclined his head.

“War shows everyone what they’re really capable of,” he replied. “Let’s hope peace does the same.”

For the first time since meeting the man, Karl felt not just respect, but a strange kinship. They were both engineers at heart—men who understood the language of machines and systems, even if they had stood on opposite sides of the conflict.

Going Home With New Eyes

Months later, when the arrangements and paperwork were finally complete, the POWs began the journey home. They boarded trains again, passed the rail yards again, and caught last glimpses of the smokestacks and assembly lines that had once seemed like scenes from another planet.

On the ship crossing the Atlantic, Karl stood at the rail and watched the coastline recede. He thought of his sister’s letters, of the town he would return to, of the factories back home that might now be nothing more than rubble.

He also thought of what might come next.

Before the war, he had imagined returning to his old profession—designing vehicles, improving engines, making small, incremental changes. Now, after everything he had seen, his ambitions felt different. If there was to be a future worth building, it would require more than repair. It would require a reimagining of what industry could be in a peaceful world.

He didn’t know if his country would have the resources, the stability, or the political will to build that kind of future right away. But he knew one thing: he would carry the memory of those American plants with him always—not as symbols of defeat, but as a blueprint for what human effort and organized energy could achieve when directed with purpose.

The hum of the factory—the endless rolling of conveyors, the rhythm of tools, the glow of lights burning through the night—had once felt intimidating, almost crushing. Now, in hindsight, it took on another meaning. It was proof that destruction and creation, tragedy and progress, were woven together by the same engines.

As he turned away from the gray horizon and walked back across the deck, Karl made himself a quiet promise. If he had any say in the future, he would dedicate whatever years he had left to building rather than breaking—to turning lessons learned in captivity into ideas that might help rebuild his homeland.

He was one man among millions, a former enemy soldier in a world struggling to decide what came next. But he had seen the power of industry up close. He had witnessed a country that harnessed factories not just to win a war, but to imagine a new era.

And he knew, beyond doubt, that the world would never be the same.

THE END

News

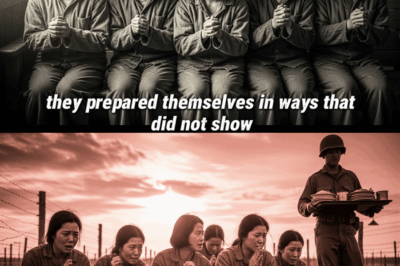

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

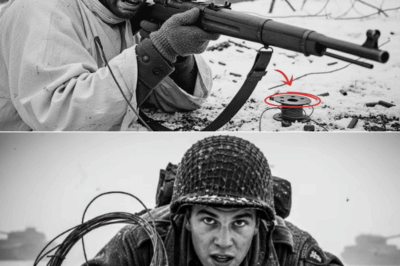

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load