Against the River Wall of the Third Reich: How Ordinary American GIs, Riding Strange Six-Wheeled ‘Duck’ Trucks, Turned the Mighty Rhine Into a Highway and Shattered German Hopes in a Single Daring Night

Corporal Joe Hennessy had seen plenty of strange things since he’d crossed the Atlantic, but nothing stranger than the “duck.”

It squatted on the muddy bank of the Maas like a metal sea monster that had crawled up from the deep—six wheels, a boat-shaped hull, a blunt nose, and a steering wheel that looked too small to control all that steel. The official name, he’d been told, was DUKW. But nobody called it that. To every GI in the 336th Amphibious Truck Company, it was just “the duck.”

Joe tugged his gloves tighter and stamped his boots against the chill. March in Europe still bit like winter. The river wind slid under his collar and down his spine.

“Quit starin’, Hennessy,” said Sergeant Al “Brooklyn” DiPasquale, climbing up the side ladder of the strange vehicle. “She ain’t gonna marry you. Get up here and check the bilge pump.”

Joe smirked and followed him up. “Sarge, if I’m gonna trust my life to a truck that swims, I got a right to stare at it first.”

“Truck that swims,” Brooklyn scoffed. “Kid, this beauty is the reason we’re gonna cross the Rhine before the other guys even unpack their boats.”

Joe didn’t argue. Truth was, he’d grown to love the duck. Back in training in England, he’d thought it was some kind of joke—like the Army had run out of real equipment and started ordering from a toy catalog. But the first time he’d driven one off the beach into choppy water, feeling the wheels leave the ground while the propeller churned behind him, he understood.

The duck didn’t care where the land ended and the water began. To it, a river was just another road.

And now, rumor said, that road led straight across the Rhine.

Orders in the Fog

The briefing came that afternoon in a cold tent that smelled of canvas, coffee, and damp wool.

A map of Germany, creased and speckled with mud, was tacked to a board. A staff captain used a wooden pointer to trace a thick blue line cutting across the country.

“The Rhine,” he said simply. Everyone leaned forward a little.

Joe knew the river’s reputation even before he’d seen it. It was the last major natural barrier before the heart of Germany. For years, planners had argued about how to cross it. Bridges blown. Current strong. Banks lined with defenses. Every rumor made it sound more like a wall than a river.

“The enemy believes we’ll need days—maybe weeks—to get enough engineers and bridging equipment in place,” the captain continued. “They don’t expect a full crossing in the first hours. That’s where you come in.”

He tapped another mark on the map. “Remagen is making headlines, gentlemen, but that bridge can’t carry enough traffic fast enough. We’re going to make our own way over—here.”

The pointer rested on a bend in the river near a small town whose name most of them had never heard before.

“Your ducks will ferry the first waves: infantry, ammo, radio sets, then light vehicles. Once we have a foothold, engineers will begin assembling pontoon bridges. But the opening hours…” He let the sentence hang. “The ducks are our secret weapon. The enemy doesn’t expect a truck that can roll down a road, then glide into the river like a boat, then crawl up the opposite bank under its own power. That surprise is our advantage.”

Brooklyn nudged Joe with his elbow. “Hear that? We’re the secret weapon. Just don’t tell my ma. She’ll worry.”

The captain continued with details: timings, call signs, load limits. Joe scribbled notes and underlined the same line three times: Watch the current. Stay in formation. No cowboy driving.

When the briefing dispersed, the mood was a mix of nervous energy and quiet pride. They weren’t glamorous paratroopers or tankers, but tonight the whole plan depended on trucks that floated and the ordinary GIs who drove them.

“Think the Germans really don’t know about the ducks?” Joe asked as they walked back to the motor pool.

Brooklyn shrugged. “They probably heard rumors. But rumors and a hundred ducks in the middle of their favorite river—that’s different. And tonight we’re bringin’ the difference.”

The River That Looked Back

They reached the Rhine just after dusk.

Joe climbed from the cab and just stood there, staring. The river filled his vision, wide and steady, sliding darkly between its banks like a moving strip of night. On the far side, lights flickered—farmhouses, maybe, or German positions.

The current spoke in a steady hush, louder than the distant rumble of artillery.

“All that water,” murmured Private Eddie Ramirez, their radio man, as he hoisted the heavy set out of the back of the duck. “Feels like it’s lookin’ back at us.”

“Rivers don’t look,” Brooklyn said, though his own eyes were fixed on the opposite bank. “They just go where they’re going. People are the ones who give ’em a reputation.”

Still, Joe couldn’t shake the feeling. The Rhine wasn’t just a line on a map. It was thick history, old stories, songs sung in bars, and speeches broadcast over radio waves. It seemed to hum with memory.

Their duck was number 12 in the company convoy. They pulled into a hollow near the bank where camouflage nets stretched between trees. The mechanics double-checked each hull plug, each pump, each tire.

“Remember,” the company commander reminded them, walking along the row of ducks, “you’re not boats. You’re amphibious trucks. That means you’re at your best when you turn water into road. Don’t sightsee out there. In, across, unload, back. Over and over. We’re the ferry that never stops.”

Joe ran his hand along the duck’s side, feeling the cold metal under the faint coat of olive paint.

“You ready, girl?” he muttered.

“Talkin’ to your vehicle again?” Eddie teased.

“You talk to that radio,” Joe shot back. “At least my girl doesn’t talk back.”

“Yeah,” Brooklyn added dryly, “but if she springs a leak, you sink. The radio just goes quiet.”

That earned a nervous laugh from all three. Humor was their shield, thin but reliable.

Waiting on the Signal

The schedule said the crossing would begin after midnight, but plans in wartime were like river water: always shifting.

They waited under blackout conditions, the ducks lined nose-to-tail like patient beasts. Somewhere down the line, a quiet engine coughed to life and then died. The night was filled with soft sounds: boots on gravel, low voices, the rustle of canvas, the clink of tools.

Joe sat behind the duck’s wheel, hands resting lightly, eyes half-closed, conserving energy. In the dark, the vehicle felt almost alive beneath him.

“You ever think about what you’ll do after this?” Eddie asked from the back, where he was checking the radio battery again.

“After tonight?” Joe asked.

“After the war.”

Brooklyn snorted from the passenger seat. “Slow down, kid. Let’s get across this river first.”

But Joe thought about it. “Go home,” he said finally. “Find a job where nothing explodes. Maybe drive something that doesn’t float.”

“My uncle’s got a little shop in San Antonio,” Eddie said. “Sells appliances. Toasters, fans, that kind of thing. He says people are gonna want electric everything when this is over. I might help him. Be nice to plug something in and have it just…work.”

“Me?” Brooklyn stretched, shoulders popping. “I’m goin’ back to Coney Island. Gonna spend a whole day eatin’ hot dogs, one after another, until I pass out on the beach. That’s my victory parade.”

The image made Joe smile. Three ordinary futures, simple and bright. For a brief moment, the war felt very far away.

A runner appeared beside the duck, breath steaming in the chill.

“Ten minutes,” he whispered. “Engines on at five. First wave lines up here.” He pointed toward the slope leading into the river.

Joe’s heart kicked a little harder. “Roger that,” he answered.

The runner vanished into the darkness, his footsteps swallowed by the soft roar of water.

“Here we go,” Brooklyn said quietly.

Into the Rhine

At the five-minute mark, engines coughed and growled to life one by one, their noise dulled by baffling and distance. The ducks rolled slowly toward the ramp, each carrying its cargo: infantry squads hunched in the back, ammunition crates, radio gear.

Joe’s duck carried a platoon from an infantry regiment that had fought its way through Belgium and the Netherlands. Their faces were a mix of exhaustion and alertness, the thousand-yard stare softened by the faint hope of being this close to the end.

An officer in a wet-looking trench coat walked along the line, his voice low but steady. “Remember: we’re not just crossing a river. We’re stepping into the last stretch before home. Keep your heads down, follow your officers, and trust the ducks.”

“Trust the ducks,” Brooklyn repeated under his breath. “Should put that on a billboard.”

Joe eased forward when the signal came: a flashlight blinked once, twice, three times. The shoreline sloped down, the river now a wide, glimmering band under the faint light of the moon.

He could feel the infantrymen behind him, their weight shifting with the vehicle.

“Hold on,” he called. “We’re going swimming.”

The duck rolled down the last few feet of earth. The front wheels touched water. A small surge splashed up against the hull.

For a heartbeat, Joe braced for the heavy sinking feeling of normal vehicles hitting water. Instead, the duck bobbed, light and buoyant. The rear wheels left the ground. The propeller engaged with a vibration he felt through the seat.

They were floating.

Joe adjusted the throttle, steering wheel surprisingly responsive. The duck nosed out into the river, following the faint silhouette of the lead vehicle. Around them, other ducks slid into the water in near silence, their wakes overlapping into a rippling tapestry.

From the shore behind, artillery began to bark—American guns firing over their heads, pounding the far bank to keep enemy defenders buried. The sky flickered with distant flashes that turned helmets and hulls briefly silver.

“Radio check,” Eddie said from behind, his voice tight but calm. “Company net is good. They’re reading our position.”

“How’s she feel?” Brooklyn asked, peering over the side.

“Like a dream,” Joe said, though his knuckles were white on the wheel. “A really wet dream.”

Brooklyn snorted. “Keep the jokes comin’, kid. If I’m gonna get famous for anything, I’d rather it be for laughin’ during a river crossing instead of screaming.”

They were halfway across when the first enemy shells began to fall.

Fire on the Water

The German artillery found its range not by seeing the ducks, which were nearly invisible in the dark, but by guessing the crossing points. Shells whistled overhead and slammed into the water in towering plumes.

One explosion sent a column of spray high into the air off their left bow. The duck rocked violently, water splashing over the gunwales.

“Keep it straight!” Brooklyn yelled, grabbing the dashboard.

“I got it!” Joe shouted back, fighting the sudden pull of the current and the blast wave. The duck wallowed for a second, then steadied. Water gurgled around their boots.

“Bilge pump!” Brooklyn snapped.

Already on it, Eddie flicked the switch. The pump hummed; a small stream of water spat back into the river.

“She’s fine,” Eddie said. “She likes the Rhine.”

“Good,” Joe muttered. “’Cause I’m not crazy about it.”

Ahead, he saw one duck veer sharply, then right itself. Another seemed to ride over a small wave rolling out from a shell impact. But none of them stopped. Line, course, speed.

In the back, the infantrymen stayed oddly quiet, helmets tipped low. Joe didn’t have to see their faces to know what they were feeling. He could almost taste the mix of fear and focus in the air.

A shell burst closer. For a second, bright light washed the water, revealing the ducks all around them: strange, low silhouettes gliding through white foam, each packed with soldiers, each carrying hopes and worries across the river.

The blast’s echo faded into the night. Joe realized he had been holding his breath and exhaled slowly.

“Almost there,” he said, more to himself than to anyone else.

Through the mist and smoke, the far bank loomed closer: dark reeds, a narrow shoreline, the suggestion of a road climbing up from the river.

Then a voice crackled over the radio, controlled but excited. “First wave approaching landing point. All ducks maintain interval. Infantry prepare to disembark at signal.”

Brooklyn twisted around. “You heard him, boys. Showtime!”

The officer in the back rose slightly, one hand on the side for balance. “When we hit, move fast,” he told his men. “Stick together. Don’t bunch up. Remember your objectives.”

Joe saw the landing point now—a slightly less steep section where engineers had cleared obstructions. It wasn’t much, but it was enough. He aimed the duck straight at it.

The hull scraped, shuddered, then began to climb. Wheels bit into mud, then earth. With a groan, the duck transformed from boat back into truck, hauling its load out of the water and onto German soil.

They had crossed the Rhine.

The First Hours

“Out, out, out!” the officer shouted.

The back gate dropped. Infantry poured out, boots slapping, rifles ready. They disappeared into the darkness and swirling smoke like figures stepping offstage into another play.

Joe barely had time to feel the weight lift from the duck before Brooklyn clapped him on the shoulder.

“Back we go,” the sergeant said. “Same road, opposite direction.”

They reversed down the slope, the duck’s rear dipping into the water again. Joe spun the wheel, turned her broadside to the current, and pointed back toward the far bank.

“Feels different going this way,” Eddie said quietly.

“Looks the same to me,” Joe replied, eyes glued to the faint outline of the return route. “Just a different kind of cargo.”

This time, they carried emptiness: space for more men, more supplies. Behind them, on the German side, bursts of small-arms fire crackled faintly. The foothold was being tested.

Trip after trip, the pattern repeated. Load on the west bank, cross under fire, unload on the east bank, return. Each time, the river seemed a little less monstrous, a little more like a hard but familiar road.

On one crossing, they carried a jeep packed with radio gear, lashed down in the duck’s belly. Joe felt the extra weight in the way the hull sat lower, the water lapping inches higher along the sides.

“Easy, girl,” he murmured. “You’re not just a truck. You’re a miracle.”

Another time, they carried stacks of ammunition crates, their sharp wooden edges digging into his knees as he squeezed past them to check a hull fitting.

“You know,” Eddie said between crossings, “if anybody had told me a few years ago I’d be ridin’ a metal duck across a famous river in the middle of the night, I’d have told them to lay off the movies.”

“This ain’t a movie,” Brooklyn replied, wiping river spray and sweat from his face with the same motion. “In movies, the vehicles never break down and nobody misses a cue.”

Yet the ducks performed. A few took shrapnel, dents appearing like bruises on their steel skins. One had an engine stutter, but another duck nudged it along until its driver coaxed it back to life. No one sank.

The Germans had not expected this. Intelligence reports later would reveal how surprised their commanders had been at the speed and scale of the crossing. They’d anticipated bridges, rafts, maybe a few assault boats. They had not imagined a convoy of wheeled machines silently slipping into the river and emerging on their side again and again, as steady as a ferry service.

For Joe, though, history and strategy were distant concepts. He was busy counting round trips.

One. Two. Three. Four.

By the fifth crossing, dawn was a pale hint behind the clouds.

Light on the Water

As the eastern sky grew lighter, the world around them sharpened.

The Rhine, now visible in muted color, showed its true width and power. Brown-green water rolled beneath them in heavy waves. Debris floated by: branches, a crate, once a helmet of unknown origin.

On the west bank, trucks and tanks lined up, waiting their turn to cross behind the infantry. Engineers wrestled with pontoon sections. On the east bank, smoke columns marked where fighting still flared.

“Look at that,” Eddie breathed on their seventh trip, pointing toward the German side. “They’re already bringing up more vehicles.”

Sure enough, a line of jeeps, armored cars, and supply trucks snaked down toward hastily improved ramps. The foothold was no longer just men with rifles; it was growing into a real bridgehead.

“We’re makin’ history,” Brooklyn said softly, almost to himself.

Joe swallowed. He could feel it too, in the way everyone moved with urgent purpose, in the way officers’ faces shifted from worry to something like cautious optimism. This wasn’t just another river. It was the river.

A burst of machine-gun fire from the far side snapped their attention back. Tracer rounds stitched across the water, still too far to reach them, but the message was clear.

“They’re not happy,” Eddie muttered.

“Would you be?” Brooklyn replied. “You wake up, look out your window, and boom—whole river full of enemy ducks.”

On the return leg, a new sound joined the thunder of artillery: aircraft.

Joe craned his neck. A flight of Allied fighter-bombers roared overhead, diving toward suspected enemy positions beyond the far bank. Explosions blossomed in the distance.

“Cover from above,” Eddie said, a hint of awe in his voice.

Joe felt a sudden surge of gratitude for all the moving parts of the operation—the pilots up there, the engineers on both banks, the artillery crews. The ducks were part of a much larger machine, each gear turning in time with the others.

But when he eased the duck onto the river for their eighth crossing, it was still just him, Brooklyn, Eddie, and a load of soldiers or supplies, trusting that this strange machine would carry them safely through.

A Close Call

It happened on their ninth trip.

They were halfway across with a load of mortar rounds and their crews when Joe felt a sudden shudder through the hull, different from wave chop or nearby blasts. The engine coughed. The duck slowed.

“Problem!” Joe barked.

Eddie checked the gauges. “Temperature’s climbing!”

Brooklyn leaned over the engine access panel, hand hovering. “Feels hot. Maybe somethin’ in the cooling intake. We pick up debris?”

The river didn’t care about plans. Somewhere below, something had shifted or clogged. Water sloshed audibly inside a compartment it shouldn’t have been in.

“Bilge pump, now!” Brooklyn snapped.

Eddie hit the switch again. The pump hummed, but the stream of expelled water was weak. Another shudder ran through the duck as the engine protested.

Behind them, one of the mortar crewmen gripped the side. “We goin’ down, driver?” he called, voice trying to sound casual and almost succeeding.

“No,” Joe said quickly. “Just giving the Rhine a drink.”

He fought rising panic. The current pushed them sideways, nudging them off their intended track. The line of ducks to their left drew farther away.

“Steering’s sluggish,” he reported. “We’re drifting.”

Brooklyn scanned the water, calculating. “We’re not takin’ on enough to sink, but we don’t want to stall in mid-river either. Can you give her a little more throttle without overheating?”

“I can try.”

Joe eased the lever forward, feeling the engine respond with a reluctant growl. The temperature gauge crept higher, needle quivering.

“Come on, girl,” he muttered. “You’ve done this nine times. Don’t pick now to get picky.”

A shell burst farther upstream, sending ripples their way. The duck rode the wave clumsily, but stayed upright.

“Radio,” Brooklyn said sharply.

Eddie already had the handset to his ear. “Duck Twelve to control, we’ve got a minor mechanical—possibly intake clog, partial flooding. Still moving, just slow. Request cover and priority landing on east bank.”

The reply came a moment later, clipped but calm. “Duck Twelve, maintain heading if possible. We’re adjusting traffic. You have engineers waiting on the far side. You’re not stopping in the middle, repeat, you are not stopping in the middle.”

“Copy that,” Eddie answered. “We ain’t fans of the middle either.”

Joe kept his eyes on the landing point and his hands on the wheel, every muscle tense. The duck wallowed like a tired animal, but it moved. Feet turned into yards, yards into more.

At last, the hull scraped mud. Wheels found purchase. The duck staggered up the far bank like a marathon runner at the finish line.

“Everybody off,” Brooklyn ordered. “Gently—she’s had a rough trip.”

The mortar teams unloaded quickly but carefully, passing rounds hand to hand. As soon as they were clear, a pair of grease-stained engineers jogged up with tool kits.

“What’s the trouble, boys?” one asked, already peering under the hull.

“Feels like we swallowed a tree,” Brooklyn replied.

It turned out to be a heavy clump of river weed and debris wedged against an intake, plus a small hull fitting that had loosened. The engineers worked fast, hands moving with the practiced speed of men who knew time meant more trips, more supplies, more lives saved.

“You’re good to go,” one said at last, wiping his hands. “Just don’t try to adopt any more underwater forests.”

Joe exhaled deeply, only now realizing how tightly he’d been holding his breath.

“Thanks,” he said. “I owe you a steak dinner when we’re back in the States.”

“You can pay me with not sinkin’,” the engineer replied. “Now get back out there. This river’s not gonna cross itself.”

The Day the River Broke

By midday, the crossing had become almost routine—which, in wartime, was another word for astonishing.

The first chaos of night had settled into an organized flow. Ducks moved in both directions along assigned lanes like commuters on a highway. The eastern bank was now a busy staging area: medics tending to the wounded, mechanics working on vehicles, officers coordinating units pushing deeper into German territory.

Joe’s shoulders ached, his eyes burned, and his hands felt glued to the wheel. But every time fatigue threatened to drag him down, something pulled him back up: a cheer from a group of infantry seeing the far shore for the first time, a wave from an engineer, the simple, steady presence of Brooklyn and Eddie beside him.

On one crossing, they carried a chaplain and his assistant along with crates of medical supplies. The chaplain, a thin man with kind eyes, sat quietly near the front, hands folded.

“First time on a duck, Father?” Brooklyn asked.

“Second,” the chaplain replied. “First was in training. It felt strange then.” He looked around at the water, at the far bank lined with advancing troops. “Doesn’t feel strange now. Feels…right.”

As they reached the eastern shore, he touched the hull lightly. “Thank you,” he said to no one in particular. “For whoever thought this up.”

Whoever had imagined the DUKW years before—some engineer sketching lines on paper—could never have pictured this exact day, this exact river. Yet his idea, turned into steel and rubber and propeller blades, was changing the course of the campaign.

Joe found himself thinking about that anonymous designer while guiding the duck across for the twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth time. Did that person know that their strange hybrid machine would someday be called a “secret weapon”? That it would help transform a feared barrier into a point of passage?

Near sunset, as the sky burned orange behind low clouds, the crossing entered a new phase. Pontoon bridges now stretched across sections of the river, their black shapes dotted with the movement of trucks and tanks. The ducks, though still busy, were no longer the only lifeline.

Still, without them, those bridges might never have been built so quickly. They had brought across the first tools, the first engineers, the first defenders.

Brooklyn watched a line of tanks rumble over one of the floating bridges and shook his head.

“Look at that,” he mused. “Bunch of heavyweights struttin’ across like they own the place. If they only knew who carried their spare parts over first.”

Joe smiled wearily. “We’re the warm-up act.”

“Yeah,” Brooklyn said. “But without the warm-up act, the main show never happens.”

Nightfall and Quiet

By late evening, the tempo slowed. The main body of forces assigned to this sector was now across. The ducks continued to ferry supplies and occasional personnel, but the sense of desperate urgency eased.

On what turned out to be their final run of the day, Joe felt every ripple in his bones. His mind replayed each crossing: the shell bursts, the near-miss mechanical failure, the faces of the men they’d carried—some cheerful, some grim, some trying very hard to look like they weren’t afraid.

When they reached the western bank and rolled up the ramp for the last time, a runner waved them to a parking area.

“Stand down for now,” he told them. “You and the other ducks from your company are going to get some rest. You’ve earned it.”

Rest. The word sounded almost exotic.

Joe killed the engine. The sudden silence felt huge after so many hours of engine rumble and radio chatter. He sat there, hands still on the wheel, unable to move for a moment.

Eddie climbed down first, stretching so hard his joints cracked. “I feel like I’ve been at sea for a year,” he groaned.

Brooklyn hopped out and patted the duck’s hull affectionately. “Good job, sweetheart,” he said. “You did your country proud.”

Joe slid down last, boots hitting solid ground that did not sway or tilt. The world seemed strangely steady.

They gathered with other crews beside a field kitchen. Someone handed them hot coffee that tasted like heaven and soup that tasted like warmth. Voices buzzed around them—other stories of crossings, small dramas and triumphs.

The company commander joined them, a rare smile breaking through his usual stern expression.

“Gentlemen,” he said, raising his tin cup, “today you turned a river into a road. The brass is already talking about how fast we got across, how completely we surprised the enemy in this sector.”

He paused, studying their tired faces.

“History books will talk about generals and divisions and strategies,” he went on. “But make no mistake: the ducks and the men who drove them were the tip of the spear today. Without you, this crossing would have taken days longer and cost a lot more lives.”

Brooklyn lifted his own cup in response. “To the ducks,” he said.

“To the ducks,” echoed voices all around.

Joe sipped his coffee and looked toward the dark line of the river, barely visible now. Somewhere on the far side, infantry units they’d carried were settling into positions, tanks were grinding forward, medics were treating wounded. The war was not over. There would be more fighting, more danger.

But something fundamental had changed. The Rhine—this legendary barrier—was behind them now, not ahead.

Letters Home

A week later, with the front line pushing deeper into Germany, Joe finally found a few quiet minutes to write a letter home.

He sat on the duck’s hood, legs swinging, the river now a distant glimmer behind a low ridge. The vehicle bore a few new scars: a patched bullet hole here, a fresh smear of paint there. To Joe, she looked more beautiful than ever.

He balanced the paper on his knee and began.

Dear Mom,

You probably saw something on the news about the big river we crossed. I can’t say too much, but I can tell you this: all that talk about it being impossible was wrong. It turns out a river is just water, and water can be crossed if you have the right tools and the right people.

He described—carefully, without violating censorship—the strange feeling of driving into the water and having the truck float instead of sink, the way the engine sounded different when the propeller took over.

We ride these things called “ducks,”

he wrote.

They’re like trucks and boats got together and decided to raise a very stubborn child. They look funny, but when you’re out in the middle of a wide river at night, with a lot of people counting on you, there’s no prettier sight than a duck that keeps on swimming.

He didn’t mention the near-miss with the clogged intake. No need to worry her. Instead, he wrote about his friends.

There’s a guy in my crew from Brooklyn who says when this is over he’s going to spend a whole day on the beach eating hot dogs. There’s another from Texas who knows more about radios than I know about anything. We all talk about what we’ll do when we get home, because that’s what keeps your feet moving when you’re tired.

He described the moment the duck’s hull scraped the far shore for the first time.

It felt like driving out of a storm into a quiet street back home,

he wrote,

except the quiet didn’t last. But that first second, when the wheels touched ground again, I thought, “We did it. We really did it.”

Near the end, he set down his pencil, thinking how to put into words what the crossing meant.

I guess what I’m trying to say,

he wrote slowly,

is that people can build walls and say “This far and no farther,” but they can only say it until someone figures out how to float a truck. Then all of a sudden, the wall turns into a doorway.

He signed the letter, folded it, and tucked it into an envelope. Somewhere along the chain of supply trucks and mail bags, it would join thousands of others—small stories traveling home from a large war.

The River, Remembered

Years later, long after the war ended and the uniforms were hung in closets or given away, people would come to the Rhine on peaceful days.

Tourists would cruise along its surface in bright boats, snapping photos of castles on hillsides. Children would skip stones from sandy banks. Couples would walk along pathways where once there had been trenches.

They would read plaques and little museum labels that said things like: Here, in March of 1945, Allied forces crossed the Rhine in a daring operation that hastened the end of the war. Innovative amphibious vehicles known as DUKWs played a vital role in the crossing.

Some would nod and move on. Others would linger, trying to imagine the night when the river was full of small, low silhouettes, engines humming, shells bursting, voices calling softly in the dark.

They might picture generals studying maps, or famous leaders on radio broadcasts. But somewhere in that mental picture, if they looked closely, they would see something else: a young driver gripping a wheel, a sergeant cracking a joke to keep fear at bay, a radio man checking his set one more time, and a strange metal duck sliding from land to water and back again as if it had always been meant to.

The Rhine would keep flowing, as it had long before and would long after. But for one long day and night, it had been something more than a river. It had been a test.

And the answer to that test had been written not in grand speeches, but in six spinning wheels, a churning propeller, and the quiet courage of the men who trusted a ridiculous-looking truck that could swim.

On the evening after the crossing, as they lay on their bedrolls under a new sky, Eddie had asked a question.

“Hey, Joe,” he said, staring up at the faint stars. “You think years from now anybody will remember the ducks? Or will they just talk about the big stuff—the bridges, the tank battles, the famous names?”

Joe, half-asleep, thought about it.

“I think some people will remember,” he’d replied. “The ones who were there, or who knew someone who was. Maybe not everybody needs to remember every detail. But as long as somebody does, it counts.”

Brooklyn, already snoring gently on the other side, stirred long enough to mumble, “They better remember, or I’m sendin’ ’em a bill for emotional damages.”

The others laughed quietly. Then the laughter faded into breathing, and the river, now behind them, kept whispering through the night like a long, slow exhale.

In that whisper was the sound of a barrier broken, of a secret weapon that wasn’t a giant gun or a new kind of explosive, but a humble, odd-looking machine and the ordinary Americans who drove it.

A river had been crossed.

A long war was one great step closer to ending.

And somewhere in the dark, a duck rested on its wheels, its steel hull still carrying the faint smell of the Rhine.

THE END

News

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived With Tin Mugs and Toast and Turned an Expected Execution Into Something No One on Either Side Ever Forgot

Facing the Firing Squad at Dawn, These Terrified German Women Prisoners Whispered Their Last Prayers — Then British Soldiers Arrived…

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate Carried Breakfast Instead—and Their Quiet Act of Mercy Ignited One of the War’s Most Serious and Tense Arguments About What “Honor” Really Meant

When Japanese Women POWs Spent the Night Expecting a Firing Squad at Dawn, the Americans Who Came Through the Gate…

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened American Soldiers to Question Everything They Thought They Knew About War”

“‘It Hurts When I Sit’: The Untold Story of Japanese Women Prisoners Whose Quiet Courage and Shocking Wounds Forced Battle-Hardened…

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard a Whispered Complaint No Medical Kit Could Fix, and Sparked a Fierce, Tense Fight Over What “Liberation” Really Meant for the Women Left Behind

“It Hurts When I Sit” — In a Ruined German Town, One Young American Lieutenant Walked Into a Clinic, Heard…

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing British Commandos They Feared Most—And How That Reputation Was Earned in Raids, Rumors, and Ruthless Night Fighting

Why Hardened German Troops Admitted in Private That of All the Allied Units They Faced, It Was the Silent, Vanishing…

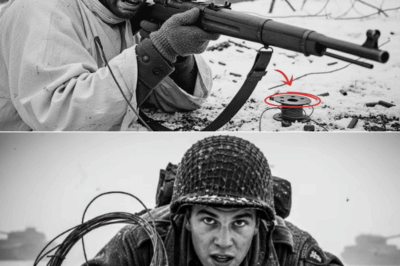

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled 96 German Soldiers and Saved His Surrounded Brothers from Certain Defeat

Trapped on a Broken Hill, One Quiet US Sniper Turned a Cut Telephone Line into a Deadly Deception That Misled…

End of content

No more pages to load