When the West Stopped at the Elbe: The Meeting Where Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton Realized the Red Army Would Reach Berlin First

The map room at SHAEF never truly went quiet. Even in the dead hours, when the corridors outside felt muffled by blackout curtains and fatigue, the place still breathed—paper shuffling, radios murmuring, a pencil tapping out someone’s private impatience.

Berlin sat on the wall map like a magnet. Everyone tried not to stare at it too long.

In early 1945, we were already deep into that strange end-of-war rhythm: miles gained, bridges taken, towns crossed off, another push planned before the last one had cooled. But Berlin wasn’t just another pin. Berlin was the kind of word that made men straighten their backs without realizing they’d slumped.

And the closer we got, the more complicated it became.

The first time I heard the idea said plainly—that the Red Army would take Berlin first—it didn’t come from a British voice, or a newspaper man, or any of the rumor factories that thrived on the edges of headquarters.

It came from an American general, in an American room, delivered like a hard truth no one wanted to be the first to touch.

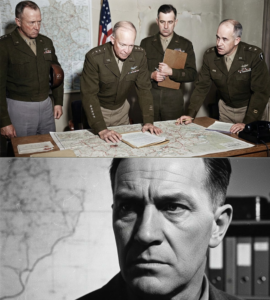

General Eisenhower stood near the main table, jacket unbuttoned, shoulders set in that calm posture he wore when everyone else was boiling. He had the kind of face that could look friendly and immovable at the same time. Around him were the men who turned his broad intentions into roads and timetables: General Omar Bradley, steady as a fencepost; staff officers with eyes like sleepless instruments; a few liaison men who watched everything twice.

Someone pointed at the Oder line on the map—thin, far to the east—where Soviet bridgeheads were already close enough to Berlin to make the city feel less like a prize and more like an appointment. The official reports suggested the Soviets were pressing hard, and no one in that room doubted they would.

Eisenhower looked at the map for a long moment, then at Bradley.

“If we go for it,” Ike asked, as casually as if he were talking about a river crossing, “what do you think it costs?”

Bradley didn’t hesitate. He had a way of answering that made you believe he’d already argued with himself about it the night before.

“Berlin would cost,” he said, “about a hundred thousand casualties.”

No one moved. You could feel the number land.

Bradley went on, voice still even: it was “a pretty stiff price to pay for a prestige objective,” especially when the Western Allies would have to “fall back and let the other fellow take over.”

That last phrase—the other fellow—did something strange in the room. It made the Red Army feel suddenly personal, not as allies on paper, but as the men who would be standing in the photographs at the end.

For months, we’d all carried an older idea in our heads, one Eisenhower himself had put into words the year before: “Berlin is the main prize,” he’d written, urging energy and resources toward a rapid thrust.

But war reshapes “main prizes” the way weather reshapes coastlines.

By early 1945, the Soviets were already close—barely forty miles out by some accounts—while British and American forces were still wrestling with rivers, logistics, and the aftershock of the Ardennes.

So the room sat with Bradley’s number and the implications that came with it.

Eisenhower finally nodded, slow and controlled, like a man accepting a diagnosis.

Then he said, “All right.”

Not all right like agreement with a plan.

All right like agreement with reality.

That’s how it begins, in most people’s minds: a neat decision, a clean pivot. As if Eisenhower snapped his fingers and Berlin simply stopped mattering.

But inside headquarters, it didn’t feel clean at all. It felt like managing a win you couldn’t fully enjoy.

Because Berlin was more than a city. It was a symbol heavy enough to bend alliances.

Churchill certainly thought so. In the cables that followed, he pressed and pressed, warning that if the Soviets took Berlin, it would strengthen their conviction that they had done everything. His argument was political, and it landed sharply because everyone knew politics was the next battlefield.

Eisenhower’s answer wasn’t theatrical. It was operational.

On March 28, he took the extraordinary step of sending a personal message to Stalin, proposing junction lines—Erfurt–Leipzig–Dresden, plus a southern link—so the final drives could be coordinated. Berlin was conspicuously absent as a stated Western objective.

And that, quietly, was the moment a lot of American generals truly understood: the race wasn’t just unwelcome—it was being called off.

Not because Berlin didn’t matter emotionally.

Because it mattered strategically in a way that could bleed you twice: once in the taking, and again in the giving back.

Even years later, Eisenhower would defend the logic with a bluntness that surprised people. Berlin, he said, was a “destroyed city,” and the “great point” of capturing it vanished if political agreements already put the occupation line far to the west. He framed it as a question no one liked to say out loud: which mothers do you choose?

In the spring of 1945, though, that argument hadn’t been polished into a public explanation yet. It was still raw. Still contested. Still something you could feel in the pauses between sentences.

And nowhere was that tension sharper than in the presence of General George S. Patton.

Patton wasn’t in that first map-room moment. If he had been, the air would’ve changed. Patton had a way of taking up space even when he didn’t speak—like a band leader arriving with the music already in his hands.

But his shadow was there anyway.

Everybody knew Patton’s mind: fast, hungry, allergic to delay. Patton didn’t like the idea of stopping short of anything that could be taken. He didn’t just want to win. He wanted to finish first—not for a trophy’s sake, he would claim, but because speed felt like the cleanest form of war to him.

And he believed—fiercely—that you shouldn’t leave the biggest symbol on the board to someone else if there was any way to reach it.

When rumors began to circulate that the Western armies would halt at the Elbe, you could watch Patton’s camp stiffen, like men bracing for weather.

A few days after that March message to Stalin, I was sent with papers to a side conference—a smaller room, fewer chairs, a table too narrow for the egos leaning over it. I didn’t have a seat. I had a corner.

Bradley was there again, steady and unsentimental. A couple of corps commanders spoke in the careful language of men who didn’t want to sound like they were pleading for glory. They asked about roads, about fuel, about bridges. They asked, without asking, if Berlin was still possible.

Eisenhower listened. He didn’t interrupt. He let them walk themselves right up to the brink.

Then he said, “We join hands with the Russians.”

It was the phrase he’d already used to Stalin—divide what’s left, link up, end it.

No Berlin. No “main prize.” Just the end.

There was silence, and then someone—too bold, or too tired—finally voiced the human part of it.

“But sir… Berlin.”

Eisenhower didn’t flinch. “Berlin is a prestige objective.”

That word again: prestige. The kind of word generals used when they didn’t want to admit they were talking about pride.

Bradley’s earlier sentence hovered over the table like smoke: a stiff price for prestige, especially if you’d have to hand it off anyway.

I watched Eisenhower’s eyes move across faces, measuring reactions the way a pilot measures cloud cover.

And I realized something: the decision wasn’t just about Berlin. It was about keeping the coalition from snapping at the exact moment victory was near.

Because there’s a special kind of danger when you’re almost done—when the enemy is fading and the allies start thinking about who will own the story afterward.

A week later, I saw Patton.

Not in a dramatic entrance, not with trumpets—just a sudden presence in the hall, brisk and sharp, moving as if every wall was in his way. His helmet was immaculate; his posture looked like it had been carved.

He paused with Bradley, a quick exchange, low voices. Bradley’s face didn’t change much, but Patton’s did—his mouth tightening into that expression that said he was hearing a decision he didn’t like but couldn’t easily challenge.

Patton walked away with the energy of a man forced to carry a stone in his pocket.

That evening, back in my quarters, I wrote in my own notebook something I’d never dare to put in an official memo:

Patton is going to hate this. And the newspapers will love it.

Because the newspapers loved conflict, and Patton—whether he intended to or not—manufactured it as naturally as breathing.

But the real conflict wasn’t shouting. The real conflict was the quiet sense, spreading through American command like ink in water, that the Red Army would claim the capital first, and that the Western armies would have to watch it happen.

At the time, plenty of men told themselves it didn’t matter. The war’s goal wasn’t a photograph. The war’s goal was to break the enemy’s capacity to continue. Berlin, in military terms, could be treated as just another wrecked city with narrow streets and a high price tag.

And yet—

Symbols don’t disappear just because you stop feeding them.

They get hungry.

In mid-April, reports came in the way they always did: too fast and too incomplete.

The Soviets launched their final offensive toward Berlin. Stalin had sounded agreeable in response to Eisenhower’s contact, and then moved with urgency anyway.

In our headquarters, that didn’t register as betrayal so much as confirmation: of course he would do it. Of course he wanted the city. Of course he wanted the story.

At the same time, American patrols pushed east, but not into Berlin—not anywhere near it, despite later myths. The Elbe became the line everyone talked about, the river that would be remembered not for its water, but for its role as a stop sign.

The day we got the first clear word that the Soviets were inside Berlin’s outer defenses, a young signals officer brought the paper down the corridor like it weighed more than it should.

I remember Eisenhower reading the message and saying nothing at first. He looked almost… relieved, as if a contest he didn’t want had ended without him having to publicly refuse it.

Bradley, standing off to one side, murmured something that sounded like a prayer and a complaint at the same time:

“Then that’s that.”

And another general—one of the quieter ones, not the sort that makes biographies—said, with a low whistle:

“History’s going to remember the flag.”

Nobody corrected him.

Because everyone knew he was right.

Months later—after the surrender, after the parades, after the world began rearranging itself into new arguments—Patton would put his feelings into words more bluntly than most men dared.

In an August 1945 diary entry preserved in his papers, Patton wrote that it was a mistake not to have advanced farther—mentioning Berlin—and he described the “great loss of prestige” in letting the Russians take “the two leading capitals of Europe.”

Whatever you think of Patton’s conclusions, you can hear the sting in that phrase: loss of prestige. Not because prestige was the goal of the war, but because prestige was going to shape the peace.

And that, ultimately, was what American generals were wrestling with in real time as Berlin slipped out of their reach.

Eisenhower saw the cost and the agreements and the coalition.

Bradley saw the math and the lives and the hard practicality of territory you’d have to surrender anyway.

Patton saw the symbol—bright, tempting, and impossible to forget.

Three ways of seeing the same city, all true, all incomplete.

I sometimes think the most revealing moment wasn’t a speech or a cable. It was a small, unguarded exchange I overheard in the hall after one of the Berlin discussions had ended.

Bradley was walking with Eisenhower, two men moving at the pace of inevitability. Bradley said something like, “They’ll say we stopped short.”

Eisenhower didn’t slow down. He didn’t look back.

He said, quietly, “Let them talk. We’ll end the war.”

It wasn’t romantic. It wasn’t headline material.

But it sounded like command.

Years later, Eisenhower would put sharper language to the same idea when political critics asked why Berlin wasn’t taken—why it wasn’t worth the cost, why it couldn’t be held given the agreed lines. He framed it as a question of sacrifice for a city already ruined.

In 1945, he didn’t need to explain it that way. He just needed to keep the machine moving until the enemy stopped.

And he did.

On the day American and Soviet troops met at the Elbe, the photographs were warm with forced friendship: handshakes, grins, men trading cigarettes and broken phrases. For a brief moment, it looked like a simple ending.

But in our headquarters, the mood was complicated. The smiles didn’t reach everyone’s eyes.

Because somewhere beyond that river, Berlin was being claimed—street by street, building by building—by another army under another flag, and the Western generals knew they were watching a chapter close without their names in its headline.

They didn’t say it in press conferences.

They said it in private rooms, in clipped estimates and careful memos and tired jokes that weren’t really jokes.

They said it when Bradley called Berlin a prestige objective with a brutal price tag.

They said it when Eisenhower told Stalin his aim was to link up and split what remained, not rush for a symbol.

They said it later, when Eisenhower defended the decision as refusing to spend lives on a city that couldn’t be kept.

And Patton said it with the kind of frustration only Patton could sustain—insisting, in hindsight, that letting Berlin go carried a prestige cost that would echo into the next era.

That’s what American generals said, in the end, when they realized the Red Army would take Berlin first:

Some spoke in numbers.

Some spoke in strategy.

Some spoke in wounded pride.

And all of them—whether they admitted it or not—understood the same uneasy truth:

The war was ending, but the story of who arrived first was already laying tracks for whatever came next.

THE END

News

In the Cellars of Berlin, They Whispered “It’s Not Rumor Anymore” as Strange Voices Rose Up the Stairwell and the City Finally Felt Its End

In the Cellars of Berlin, They Whispered “It’s Not Rumor Anymore” as Strange Voices Rose Up the Stairwell and the…

The Night Churchill Read the Cable on Metz—and Repeated One Razor-Quiet Sentence That Explained Patton Better Than Any Headline Ever Could

The Night Churchill Read the Cable on Metz—and Repeated One Razor-Quiet Sentence That Explained Patton Better Than Any Headline Ever…

Inside the Frozen Ardennes: The Night Patton Swung North, Tightened a Steel Noose, and Made the German High Command Whisper the Unthinkable

Inside the Frozen Ardennes: The Night Patton Swung North, Tightened a Steel Noose, and Made the German High Command Whisper…

The Day Patton Beat Montgomery to Messina—and the Quiet, Cutting Line Eisenhower Used to Save the Alliance Before It Shattered

The Day Patton Beat Montgomery to Messina—and the Quiet, Cutting Line Eisenhower Used to Save the Alliance Before It Shattered…

The “Impossible Blueprint” Rumor: How a Midnight Engineer, a Thunderbolt Pilot, and One Sky-Colored Trick Made German Flak Miss the P-47s

The “Impossible Blueprint” Rumor: How a Midnight Engineer, a Thunderbolt Pilot, and One Sky-Colored Trick Made German Flak Miss the…

“Sleep Without Your Uniforms Tonight”: The Midnight Sanitation Order That Turned a German Women’s POW Camp Upside Down—and the Hidden Reason No One Expected

“Sleep Without Your Uniforms Tonight”: The Midnight Sanitation Order That Turned a German Women’s POW Camp Upside Down—and the Hidden…

End of content

No more pages to load