When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six Hours Later, His Lone Gamble Turned Their Mockery into Shock, Freedom, and a Furious Argument in the War Room

By the time the rumor reached the front line, it sounded like a bad joke.

“Fifty thousand Canadians, all in one camp,” someone said over tin mugs of bitter coffee. “Guarded by half the German army. We’re going to need a miracle or a magician.”

In the corner of the muddy tent, Corporal Owen Daly adjusted the black patch over his left eye and said quietly, “You don’t need a magician. Just a scout.”

The men around him laughed, more from nerves than cruelty.

“Sorry, Corp,” one of them smirked, jerking a thumb at the patch. “We’re fresh out of scouts. Got a one-eyed bloke, though.”

More laughter.

Owen smiled thinly and went back to cleaning his rifle. He’d heard worse. He’d heard it when the field surgeon told him the shrapnel had taken the eye for good. He’d heard it when the board reviewed his file and stamped fit for limited duty in a way that made it sound like a favor.

He’d heard it every time someone said “scout” and then remembered—too late—to glance at the patch and tack on something like, “Well, I mean, used to be.”

Only one person in the tent didn’t laugh.

Major Claire Kincaid, Canadian Army, stood near the map board, arms folded, watching Owen.

“You’ve seen it,” she said.

It wasn’t a question.

Owen looked up.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. “Six days ago. Before they tightened the net. Long walls. Floodlights. Guard towers every fifty yards. Rail line feeding straight into the yard. Lot of barbed wire.”

“And?” she asked.

He hesitated.

“And a weakness,” he said.

The other men rolled their eyes.

“Of course he says that,” someone muttered. “Scouts. They see ‘weaknesses’ the way priests see sins.”

Kincaid rapped the map board with her knuckles.

“Quiet,” she snapped.

Silence fell.

She turned back to Owen.

“Report,” she said.

Owen set the rifle aside and stepped closer to the map.

A red square indicated the camp—an inland fortress surrounded by flat, open ground and a shallow river like a defensive ditch. On the board, it was just pencil and paper. In his mind, it was mud, stone, echoes, and the metallic scent of fear.

“High fences,” he said. “Double row of wire, with a ‘no man’s land’ in between. Inner guard path. Outer patrols. But the Germans built it fast. They used what was there.”

“What was there?” Kincaid asked.

“A marsh,” he said. “They drained it as best they could. Laid rock fill, poured concrete for the main road and the rail spur. But on the north side, about here—” he tapped a corner of the square “—they had to put in culverts to manage runoff. Three of them. Big concrete pipes. One of them cracked during the last storm.”

He could still hear the trickle of water through the broken pipe, the hollow echo of his own breath when he’d slid down to have a look.

“You went inside,” Kincaid said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Alone.”

He shrugged.

“That’s the job, isn’t it?”

Someone near the stove snorted.

“Real heroic, crawling around in drains.”

Owen ignored him.

Kincaid didn’t.

“Corporal Hughes,” she said without looking over. “Remind me to volunteer you for the next drain.”

A low chuckle ran through the tent, this time at Hughes’ expense.

Kincaid leaned closer to the map.

“The crack,” she said. “Big enough?”

“For a man my size,” Owen said. “Maybe not for Hughes.”

Someone laughed again, more gently.

Kincaid’s jaw tightened.

“You think you can get in that way,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“And then what?” a new voice cut in.

Colonel Dufort, divisional operations, had entered quietly, his greatcoat dripping snow. His tone was dry as old paper.

“You stroll into a German camp that’s holding half our captured division and ask them politely to unlock the gates?”

Owen straightened.

“No, sir,” he said. “I make it so they unlock themselves.”

Dufort raised an eyebrow.

“Go on,” he said.

Owen swallowed.

He wasn’t used to this many eyes on him.

“In the middle of the camp,” he said slowly, “there’s a communications block. Concrete. Small windows. I saw antennae on the roof. Field telephone cables running out. They’re running this place by wire and habit. Patrol schedules, guard rotations, alerts—all of it depends on those lines and their trust in them.”

He tapped his temple.

“Cut the right lines, confuse the wrong ones, and you turn order into chaos,” he said. “Chaos opens doors. And if those doors open at the right time, when we’re ready to push—”

“—we get a slaughtered camp,” Dufort interrupted. “Fifty thousand unarmed men in the middle of a firefight.”

The air in the tent dropped ten degrees.

Owen’s throat tightened.

“No, sir,” he said. “Not a firefight. A withdrawal.”

Dufort stepped closer.

“You’ve been inside this place once, looking from the outside in,” he said. “You think that makes you an expert?”

“No, sir,” Owen said. “It makes me a witness.”

The colonel’s eyes flicked to the patch.

“And your depth perception?” he asked. “Your night vision?”

Owen felt the old flash of anger.

“Compensated for,” he said. “I’ve been retrained on the range. I can still hit a helmet at three hundred yards. I can still read terrain. Losing an eye sharpened everything else, sir. You learn to listen harder when there’s less to see.”

Hughes muttered under his breath, just loud enough.

“Maybe we should knock out everyone’s eye, then.”

A ripple of unease followed.

Kincaid’s head snapped toward him.

“Out,” she said.

“What?” Hughes blinked.

“Out,” she repeated. “Cool off. Now.”

He hesitated, then trudged out of the tent, the flap snapping shut behind him.

Dufort returned his attention to Owen.

“What exactly are you proposing?” he asked.

Owen took a breath.

“A single-man infiltration,” he said. “I go in through the culvert. I avoid the lights. I reach the comms block. I cut the external lines to their higher headquarters so they can’t call for help. Then I loop a few internal circuits.”

“Loop?” Kincaid asked.

“Connect the wrong lines to the wrong phones,” he said. “Make the tower think the perimeter’s been breached in three places at once. Make the German guards hear their own officers giving conflicting orders. Then, at the right moment, I trigger the alarms.”

“What alarms?” Dufort asked.

“Air raid sirens,” Owen said. “They’ve got them rigged to a manual switch inside. I saw the box through a window. If I set them off in the middle of my chaos show, they’ll think they’re under air attack. Standard German procedure, from what intel says: lock down the outer perimeter, pull guards in tight, get everyone into shelters, prepare to move the camp if it looks like they’re about to be overrun.”

“And how does this—” Dufort gestured vaguely “—free fifty thousand men?”

“They’re not cattle, sir,” Owen said quietly. “They’re soldiers. They’ve tried to break out before. They’re just waiting for a crack that isn’t suicidal.”

He pointed at the north gate on the map.

“There’s a vehicle gate here,” he said. “Heavy, but it moves. If I can get to the control wheel and wedge it open just enough, then cut the right lights… and if, at that exact time, our artillery drops a pattern on the eastern wall, drawing the guards that way…”

He met Kincaid’s eyes.

“…and if someone inside gets the signal that this is it, they’ll do the rest. Mass push. Over the inner fences, through the gap, out into the dark, toward our lines. We can have transport waiting on the road. Six hours from first siren to last truck, if we plan it right.”

Dufort stared at him.

“For this to work,” he said slowly, “you need the following: perfect timing, flawless stealth, accurate understanding of German procedures, and fifty thousand starving men able to run in the snow under fire.”

Owen didn’t flinch.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“And if any of it fails?” Dufort pressed. “What then? We trigger a panic. Guards fire into the compound. Men die trampled, shot, frozen in the wire. And we”—his jaw clenched—“we will have done that to our own.”

The tent went utterly quiet.

Owen swallowed.

“Sir,” he said, voice low, “they’re already dying in there. Slow. Quiet. One by one. Dysentery. Pneumonia. Beatings. Work details that don’t come back. We’ve seen the numbers. We know how many went in and never came out.”

He felt his hand curl into a fist.

“We can’t sit here and hope the war ends before the math does,” he said. “We either try something or we sign off on letting them fade away behind a fence.”

Dufort looked at Kincaid.

“You support this?” he asked.

She didn’t answer immediately.

When she did, her voice was steady but not gentle.

“I think,” she said, “that if anyone can get in and out of that place without being seen, it’s Daly. I also think this plan is a miracle disguised as a suicide note.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” Owen muttered.

“Not a compliment,” she shot back, but there was a glint in her eyes. “Just truth.”

Dufort’s jaw worked.

“The higher command will never sign off,” he said. “We don’t have authorization for a raid, much less an improvised jailbreak of this scale. They’ll say we risk losing the only bargaining chip we have.”

Kincaid frowned.

“Bargaining chip?” she repeated.

“For negotiations after the war,” Dufort said. “Prisoner exchanges. Reparations. They’re thinking on a level above our pay grade.”

“That ‘chip’ has names,” Kincaid said coldly. “Faces. I taught with some of their fathers. I saw some of them off at the train station. They’re not numbers on a ledger, sir.”

“And yet the ledger exists,” Dufort said tiredly.

The air in the tent thickened.

The argument was no longer theoretical.

It was about what kind of army they were.

What they were willing to risk.

What they were willing to live with later.

“The order from corps is clear,” Dufort said. “Hold the line. Wait. When the larger offensive rolls, the camp will be liberated in due course.”

“In due course,” Kincaid repeated. “Which could be weeks. Months.”

“War is fought on schedules, Major.”

“Tell that to twenty-year-olds in a winter cage.”

Their voices rose.

They weren’t shouting yet, but the edges sharpened.

Owen stood very still, feeling the heat between them like a fire he’d accidentally started.

Finally, he took a breath.

“Sir,” he said quietly.

They both turned to him.

“If I go now, tonight,” he said, “it’s on me. Give me six hours. If I don’t make it, you can say I went off grid. I’ll write the letter myself if you need it. Soldier went missing on unauthorized recon. The plan never leaves this tent. You’re covered. The only one who pays is me.”

Kincaid’s head whipped toward him.

“Absolutely not,” she snapped. “We don’t sacrifice people like that. Not on my watch.”

“It wouldn’t be a sacrifice if it works,” he said.

“And if it doesn’t?” she demanded.

He met her gaze.

“Then I’m one more ghost in a war full of them,” he said. “And I’ll still sleep better—in whatever comes after—knowing I tried.”

“The higher-ups will roast you,” Dufort warned. “If you live.”

Owen smiled grimly.

“If I live, I’ll deal with that problem when it arrives,” he said. “Sir, please. This is what I was trained for. To go where others can’t. To see what others miss. You don’t need both eyes for that. You just need to know what you’re willing to risk.”

Dufort stared at him a long time.

Then he looked at Kincaid.

The argument hung between duty and conscience.

War and humanity.

“I can’t sanction this,” he said at last. “Officially.”

Kincaid closed her eyes briefly.

“Unofficially?” she asked.

He hesitated.

Then:

“Unofficially,” he said, “if a certain scout were to go out on a routine perimeter check and not return on time, and if, during that window, we were to register unusual activity on the enemy side, and if, by some extraordinary coincidence, the camp’s outer lights went dark at 0300…”

Kincaid’s breath hitched.

“And if,” he continued slowly, “we had, entirely coincidentally, pre-registered artillery at a point east of the camp for ‘future use’ and chose that moment to fire a diversionary pattern…”

A thin, dangerous smile touched his mouth.

“…then any freedom that resulted might be attributed to enemy panic. Or divine intervention. Or whatever story headquarters finds easiest to swallow.”

Kincaid let out a breath she hadn’t realized she’d been holding.

“Thank you, sir,” she said softly.

“I didn’t say yes,” Dufort snapped. “I said nothing you can quote.”

He turned back to Owen.

“You have six hours from step-off,” he said. “No more. If you’re not back or the situation hasn’t changed by then, we assume you’re gone and we go back to waiting. Understood?”

“Yes, sir,” Owen said.

“And Daly?” Dufort added. “Don’t be a martyr. Be effective.”

Owen nodded.

“I’ll do my best,” he said.

He stepped off twenty minutes after midnight.

Snow fell in a fine veil, muffling the world. The moon hid behind clouds. Perfect.

He left his unit’s patch off his sleeve. If he was captured inside the fence, it would buy his comrades a sliver of deniability.

His remaining eye had adjusted long ago to the shadow world. Depth came from sound, timing, the way shapes shifted as he moved. He read the forest like a book written in grayscale.

He reached the river that curved like a lazy question mark around the camp and slid down the bank on his belly.

The water was shallow but bitterly cold.

It soaked his sleeves, crept under his collar.

He gritted his teeth and crawled.

At the north corner, he found the culvert inlet—a dark, round mouth half clogged with ice and debris.

He listened.

No voices.

No footsteps above.

Good.

He slid inside.

The concrete scraped his shoulders.

The trickle of water echoed.

Every sound felt amplified, enormous.

He counted his breaths, his motions, his faith.

Halfway through, where the pipe had cracked in the last storm, a sliver of gray light bled in from above.

He paused, pressed his ear to the crack.

Muffled footsteps.

A cough.

Guard tower nearby.

He waited until the steps faded.

Then he wriggled on.

The pipe opened into a larger drainage chamber.

He emerged into knee-deep water and the smell of rust and mold.

Above him, a metal grate.

Through it, he saw the bottom of the inner fence, the churned mud of the yard, the edge of a low building—latrines.

He took a breath.

Then another.

Then, timing it between the lazy arcs of a searchlight, he pushed the grate up, slid it aside, and flowed out like a shadow into enemy territory.

He cleared the fence, flattened against the wall, and listened.

Voices.

German, overlapping.

A guard complained about the cold.

Another complained about the prisoners’ smell.

Owen catalogued the sound of each voice, the rhythm of each step.

Then he moved.

He slid from shadow to shadow, hugging the sides of low buildings, ducking under windows, freezing when a patrol passed within arm’s reach.

Twice, a guard’s flashlight beam swept over him and slid on, dismissing him as just another patch of dark.

He made it to the communications block without firing a shot.

Up close, it loomed like a squat bunker, lines of cable running into its sides like veins into a heart.

Two sentries stood at the door, stamping their feet, rifles slung.

Owen waited behind a coal pile, watching.

The shift change came on the hour.

Two fresh guards approached.

For thirty seconds, all four were at the door together, backs half-turned as they exchanged pleasantries and cigarettes.

Owen chose that moment.

He picked up a fist-sized chunk of frozen mud and hurled it against the far wall with just enough force to make a sharp crack.

The sound snapped across the yard.

All four guards flinched, heads turning toward it.

Someone muttered, “Was war das?”

Owen moved.

He crossed the gap to the service hatch he’d seen in his recon—a waist-level metal door near the ground.

He’d oiled its hinges on his last visit, quick and quiet, trusting they hadn’t noticed.

Now, it opened like a sigh.

He slipped inside, closing it behind him.

The comms room smelled of dust and metal.

Racks of field telephone equipment lined the walls—switchboards, battery cases, neatly coiled wires.

A single operator sat with his back to Owen, headphones on, cigarette smoldering in an ashtray, scribbling notes in a log.

Owen stepped lightly.

The German shifted in his chair, humming under his breath.

Owen brought the butt of his rifle down on the man’s head in one sharp, measured blow.

The operator went limp, slumping sideways.

Owen caught him, eased him to the floor, and dragged him behind a rack of equipment.

He bound the operator’s wrists with a stripped length of cable and stuffed a rag between his teeth.

“Sorry, mate,” he whispered, more habit than malice. “You get to sit this one out.”

He turned to the switchboard.

Lines.

Dozens of them.

Each labeled in neat, angular handwriting.

Tower.

Gates.

Outer patrols.

Barracks.

Commandant.

He smiled faintly.

“Well,” he murmured, “let’s see what mischief we can learn.”

He lifted a handful of connectors, tracing them.

He’d done telephone work before the war, stringing lines in rural Ontario.

He knew how systems thought.

He unplugged the line labeled “Tower North” and swapped it with “Gate East.”

He moved “Barracks 2” to “Commandant.”

He took “Outer Patrol West” and looped it into a dead line.

Then he slit the main trunk that led out of the building toward the higher headquarters, stripping it with his knife and twisting it into a neat, useless knot.

The camp was now, electrically speaking, a man trying to shout with his hands over his own ears.

He slipped on the operator’s headphones, more for show than use, and tapped a key.

“Turm Nord, melden,” a voice crackled in his ear.

North tower, report.

Owen grinned.

He pitched his voice a little higher, cluttered his German on purpose.

“Hier Tor Ost,” he said. “Aktivität am Zaun. Möglicher Fluchtversuch. Bestätigen Sie Ihre Seite.”

Here east gate. Activity at the fence. Possible escape attempt. Confirm your side.

Static.

Then a flurry of excited chatter.

Another line lit.

“Barracks,” someone barked. “Was ist los am östlichen Zaun?”

What’s happening at the eastern fence?

Owen switched lines again.

“Hier Turm Nord,” he replied, pretending to be the tower now. “Wir sehen Bewegung im Schatten. Können die Lichter nicht halten. Mögliche Sabotage.”

We see movement in the shadows. Can’t keep the lights steady. Possible sabotage.

He worked the board like a piano, sending misinformation into every loop.

South gate called in to report quiet conditions and got redirected into a dead line.

The commandant’s quarters rang and got Barracks Two instead, where a bored guard answered with a confused, “Hallo?” and then cursed as someone shouted at him.

Within ten minutes, the camp’s command net was a snake eating its own tail.

It was time.

Owen found the alarm box on the wall—a sturdy metal panel with a lever and a label: Luftalarm.

He placed his hand on it.

This was the hard part.

If he pulled it, there was no going back.

If he didn’t, he’d crawled through a river, a pipe, and a dozen shadows for nothing.

He closed his eye for a heartbeat.

He saw a field of little white crosses that hadn’t yet been planted.

He saw names on telegrams waiting to be written.

He saw the thin figure he’d glimpsed for half a second through the wire on his first recon—a Canadian sergeant with hollows under his cheekbones, staring toward the horizon like he was watching the inside of a clock run down.

He pulled the lever.

The sirens wailed.

They rose in a mournful, mechanical scream that ripped through the night and drilled into bone.

Lights snapped on.

Shouts erupted.

Boots pounded.

Guards muttered, yelled, tripped over each other.

Owen listened to the lines explode with noise.

“Flugzeuge gesichtet?”

“Noch nicht—”

“Alle Posten, Bericht!”

“Sirenen im Westen auch—”

“Wer hat den Alarm ausgelöst?!”

He smiled grimly.

Not your finest hour, lads.

He slipped out of the service hatch, blending into the panic.

Guards were running toward designated positions, checking weapons, craning necks at the sky.

Some shouted for prisoners to get down.

Others shouted conflicting orders.

Chaos.

He moved along the inner fence, keeping low.

At a corner of the yard, he saw them.

Canadians.

Hundreds crowded together in the dim light, wearing threadbare greatcoats and improvised boots, faces gaunt.

Some sheltered others with their bodies.

Some just stared.

He whistled, low and sharp.

A man near the fence looked up.

Sergeant stripes, faded but visible.

He stepped closer, squinting.

When he spoke, his voice had the flat vowels of the Prairies.

“You’re not one of them,” he said softly. “Not with that accent.”

Owen ducked so only the man could see him.

“Corporal Owen Daly, Third Division,” he whispered. “I’m not here. You never saw me.”

The sergeant’s eyes widened.

“How—”

“No time,” Owen cut in. “Listen. In four minutes, the east side lights will flicker. When they do, you get everyone in Barracks Three and Four ready to move. Over the inner wire, across the yard, toward the north gate. Spread the word in whatever way you can that this is not a drill. Understood?”

The sergeant’s jaw clenched.

“You’re insane,” he said.

“So I’ve been told,” Owen replied. “Can you do it?”

A muscle in the sergeant’s cheek jumped.

He looked back at the mass of men huddled behind him.

“This is going to be a bloodbath,” he said.

“Not if you move fast,” Owen said. “Not if the guards are looking the wrong way.”

The sergeant’s eyes slipped to the patch.

“And if it gets worse?” he asked. “If half of them don’t make it?”

Owen’s throat tightened.

“Then at least the other half had a chance,” he said. “Right now, you’re on track to see none of you walk out of here alive. Sirens or no.”

The sergeant held his gaze.

Something passed between them—a silent argument, fierce and fast.

Then the sergeant nodded once.

“All right, Daly,” he said. “We’ll play your crazy hand. What’s the signal?”

“You’ll know it,” Owen said. “Trust me.”

He slipped away toward the north gate.

Trust me.

He didn’t know if he trusted himself.

At the gatehouse, two guards argued in the open doorway about whether they’d heard engines in the distance.

One insisted it was trucks.

The other insisted it was the wind.

Neither noticed Owen slide along the wall to the control wheel that raised and lowered the main gate—a heavy metal disc connected to gears.

He gripped it.

Cold bit into his fingers.

He spun it slowly, easing the gate up two inches.

The chain groaned.

He froze.

Inside the gatehouse, one guard paused mid-sentence.

Then he went back to complaining about his boots.

Owen slid a length of scavenged wood into the track to wedge the gate in its slightly raised position.

Now, a concerted push from inside would make it jump.

He double-checked the wheel.

Then he moved back toward the comms block, hugging the shadows.

Above, the night sky was still empty of bombers.

The sirens wailed on.

Three minutes.

He reached the comms building and ducked inside.

The operator was still unconscious, breathing shallowly.

Owen unplugged the main feed to the eastern floodlights and crossed it with a line that seemed harmless.

The eastern yard went dark.

Guards shouted.

Searchlights swept uselessly.

Owen waited ten seconds.

Then he hit the floodlights again, letting them flare, then cut, then flare, mimicking a failing generator.

In the yard, confused shouts rose.

“Was ist los mit dem Strom?!”

“What’s wrong with the power?!”

Prisoners’ heads snapped up.

The sergeant he’d spoken to shouted something.

Men surged toward the inner fences, not yet rushing, but ready.

Now.

Owen killed the lights completely.

Darkness dropped on the east side of the camp like a curtain.

He ripped the line out and let it hang.

On the western wall, German guards fired shots into the night—warning bursts, panicked.

At that precise moment, far beyond the camp, Allied artillery boomed.

Shells screamed overhead and detonated along the eastern perimeter, outside the walls but close enough to shake the ground and shower dust.

To German ears, it sounded like the start of an assault.

To Canadian ears, it sounded like a door being kicked open.

The yard erupted.

Prisoners surged toward the fence, shoving over the inner wire, throwing blankets and boards over the coils, climbing, tumbling, clawing.

Guards shouted.

Some fired into the air, trying to intimidate.

Others hesitated, unsure of their orders in the confusion.

Owen heard the comm lines explode with overlapping commands.

“Halten Sie die Gefangenen zurück!”

“Alle zum Westtor!”

“Nein, verteidigt den Osten—”

“Wer hat die Artillerie gerufen?!”

He smiled grimly.

Good.

Keep arguing.

He ran back toward the north gate, heart pounding.

By the time he reached it, a wave of Canadians was already crashing against the inner fence nearby.

The sergeant from before was at their head, one hand on the wire, yelling for others to climb.

In the intermittent flashes from distant explosions, Owen saw shapes moving like a tide.

He heard someone shout in English, “Now! All together! PUSH!”

They hit the gate as one mass.

The wedge Owen had placed bit, groaned, and finally slipped.

The gate lurched upward another foot.

The men hit it again.

It jumped its track and rolled up just enough for bodies to crawl under, then squeeze, then surge.

The first Canadians spilled through like water from a burst dam.

German guards at the gate fired wildly, but their shots went high—aiming at shadows rather than exact targets.

Prisoners disappeared into the dark beyond the fence, running for the treeline where Owen had come in.

The plan was working.

If he had time to feel relief, he did not know it.

Because that was when everything turned.

“DEUTSCHER SPÄHER!”

German scout!

The shout came from behind him.

He spun.

A guard had spotted his silhouette in the wrong place, the wrong shape.

The patch was hidden under his helmet band, but his posture, his gear—it looked wrong.

A rifle barked.

Something slammed into his shoulder, spinning him.

He hit the ground hard.

Pain flared, sharp and hot.

He rolled, instinct carrying him into the shelter of the gatehouse wall.

The guard shouted again, calling for others.

The comm net crackled.

“Unbekannter Soldat am Nordtor!”

Unknown soldier at the north gate.

Owen’s vision tunneled.

Not now.

Not yet.

He gritted his teeth and dragged himself upright with his good arm.

He saw the guard raising his rifle again.

A Canadian prisoner tackled the guard from the side, driving him into the mud.

The rifle went off, muzzle flashing into the sky.

Another guard swung the butt of his weapon at the prisoner’s head.

The prisoner went down.

Owen raised his own rifle one-handed and squeezed the trigger.

The guard jerked, staggered, and fell.

It was his first shot of the night.

He hoped it would be his last.

The yard dissolved into chaos.

Prisoners swarmed.

Some fought hand-to-hand.

Some simply ran.

Guards shouted, fired, retreated, or threw down their weapons rather than be crushed.

From his vantage point, Owen saw what he’d hoped for:

The majority of guards withdrawing toward the western side of the camp, where the artillery had focused, convinced an assault was coming from that direction.

The north gap remained a wound, bleeding men.

He reached for his field radio with trembling fingers.

“Kincaid,” he rasped. “This is Daly.”

The reply was instant.

“Daly, for God’s sake, where—”

“North gate,” he said. “Gap’s open. Prisons are flooding out. You’ve got maybe five hours before the Germans figure out they’re not under full-scale attack.”

He swallowed hard.

“Get the trucks.”

“Already moving,” she said. “We started as soon as the sirens went.”

Of course she had.

He should have known.

“Your status?” Kincaid asked.

“Bit holed,” he said, glancing at the spreading warmth on his shoulder. “Still ticking.”

“Can you reach the river?” she asked.

He looked toward the culvert, where the darkness yawned like a promise.

“I can try,” he said.

“Then you try,” she ordered. “And if you can’t, you find a hole and stay in it. Our boys will be coming the other way soon enough.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

He shut off the radio.

Then he ran.

Or something like running.

It was more of a lurching, stubborn forward motion.

At some point his arm went numb.

At another he realized he’d dropped his rifle.

It didn’t matter.

His job now was to leave.

The machine he’d set in motion was bigger than him.

He slid under the inner fence, ignoring the sting of barbs, and reached the grate to the drainage chamber.

He dropped down, dragging himself with his good arm.

Cold water hit his face.

The sirens wailed and wailed above.

He crawled.

Every scrape of concrete against his knee felt like fire.

Time distorted.

The pipe was endless.

But eventually he smelled the river again.

He felt fresh air.

He emerged on the far bank, half in the water, half in the mud, and lay there, panting, watching steam curl from his own body in the cold.

Behind him, the camp roared.

Ahead of him, the forest waited.

He closed his eye.

He did not remember the next part clearly.

There were shapes.

Hands.

Voices.

Someone shouting his name.

Then, much later, light too bright to be moonlight.

Clean sheets.

The smell of antiseptic.

He drifted in and out of a haze of morphine and memory.

When he finally woke fully, Kincaid was sitting in a chair by his bed, coat off, sleeves rolled, hair pulled back in a way that said she’d forgotten about it hours ago.

“You look terrible,” she said.

“You should see the other guy,” he croaked.

He tried to move his left arm.

It refused.

He glanced down.

Fresh bandages.

No new missing parts.

He sighed.

“How long?” he asked.

“Thirty hours,” she said. “You’re in a field hospital, ten kilometers from where I last threatened to have you court-martialed.”

He blinked.

“How many?” he whispered.

She knew what he meant.

She picked up a folded paper from the table and handed it to him.

It was a rough, hand-written list.

Numbers.

Estimates.

“Fifty thousand were there,” she said quietly. “Canadians, mostly. Some British, some others. We don’t know exactly how many got out yet. At least forty thousand, maybe more. Some were too sick to move. Some… chose to take their chances in the chaos and didn’t make it. But the camp is empty now. The Germans tried to round up whoever they could in the surrounding woods. Our units engaged them on the east road. It’s done.”

Owen stared at the paper.

The numbers blurred.

“Forty thousand,” he said.

“At least,” she repeated. “And counting.”

He swallowed.

“Any… blowback from upstairs?” he asked.

She exhaled.

“We were just in a meeting when you woke up,” she said. “It got… heated.”

That was an understatement.

The war room looked like every other: maps, pins, cigarette smoke, weary faces, clattering typewriters.

But the mood was electric.

Divisional command, corps representatives, liaison officers from allied units—they were all there.

Dufort stood at the head of the table, jaw tight.

A colonel from corps—smooth, pressed, remote—tapped a pencil against a file.

“So,” the corps colonel said, “you are telling me that a single corporal, acting without official authorization, triggered an unsanctioned prisoner uprising that could easily have ended in catastrophe.”

“With respect,” Dufort said, “the catastrophe was already in progress. We simply interrupted it.”

The corps colonel’s mouth thinned.

“I understand the desire to paint this as a heroic incident,” he said. “But do you realize what would have happened if the Germans had responded differently? If they’d decided to simply… remove the problem?”

“You mean, shoot the prisoners,” Kincaid said flatly.

He frowned.

“I mean, execute a scorched-earth policy,” he said. “Our intelligence suggests such orders exist.”

“Our intelligence also suggested the camp’s population would be reduced by half over the next four months even under ‘normal’ conditions,” Dufort retorted. “I chose the gamble that didn’t involve a slow bleed.”

The corps colonel turned to a British liaison officer.

“And what will London say,” he asked, “when they learn that Canadian units took it upon themselves to unilaterally liberate a camp holding not only their own men but British prisoners as well, without coordinating with the agreed overall strategy?”

The British officer shrugged, tired.

“I imagine,” he said, “that some will be cross about the paperwork, and many more will be delighted not to have to write certain letters home.”

The corps colonel’s cheeks colored.

“This is not a joke,” he said. “War is not run on… on improvisation and sentiment.”

“Could have fooled me,” Kincaid muttered.

He rounded on her.

“Major,” he said sharply. “Explain to me how you justify risking the lives of tens of thousands of prisoners on the whims of a one-eyed scout.”

The room went very still.

Kincaid stood.

Her chair scraped.

“First,” she said, “I don’t justify it. I live with it. There’s a difference. Second, it wasn’t whim. It was a calculated risk based on firsthand reconnaissance and the expertise of the man you just called a ‘whim.’”

“Expertise?” the colonel scoffed. “He is impaired. That patch—”

“Is covering an eye he lost doing his job,” she snapped. “He’s forgotten more about German wiring, terrain, and patrol habits than most of us at this table will ever know.”

The colonel opened his mouth.

She didn’t let him.

“And third,” she said, voice hardening, “war may be run on timetables up here, but out there?” She jabbed a finger toward the wall. “Out there it’s mud and hunger and frostbite and numbers scratched on the inside of huts to count how many of your mates died this week. Out there, waiting is the risk. Doing nothing is a decision. We made a different one.”

The colonel’s jaw clenched.

“This kind of undisciplined heroism creates chaos,” he said coldly. “You’ll have every corporal in the theater thinking he has the right to rewrite operational plans.”

Dufort spoke up.

“Only the ones with the courage to take the consequences on themselves,” he said. “We didn’t send him. He went. We didn’t order the artillery. We suggested a training pattern be fired at an appropriate time. We acted in the gray, because the black and white were killing people.”

“This could have blown up in your faces,” the colonel argued.

“It did,” Dufort replied. “Just not the way you mean. The only ones who got hurt are the ones who were already bleeding. And the ones responsible for that are on the other side of the wire, not on this side of the table.”

The argument went on.

Serious.

Tense.

At points, inches from outright insubordination.

In the end, higher command did what higher command often did when presented with a fait accompli that was both tactically advantageous and politically messy:

They buried the bad parts and polished the good ones.

The official report would later say that “a combination of enemy miscalculation, prisoner initiative, and opportunistic Allied support resulted in the liberation of Camp 47.”

No mention of a culvert.

No mention of a switchboard.

No mention of Corporal Owen Daly’s name.

Not in the first draft, anyway.

Kincaid made sure that changed.

“If you’re going to tell the story,” she said, “you’re going to tell the whole thing. Or I will.”

The corps colonel glared.

“You’re playing a dangerous game, Major,” he said.

“So is he,” she replied. “Now.”

When she finished recounting the meeting, Owen lay back on his pillow and let out a long breath.

“So, I’m both a problem and a propaganda opportunity,” he said.

“Pretty much,” Kincaid said. “They’ll probably tidy it up for the papers. Trim the rough edges. ‘Brave prisoners seized the moment when German guards panicked under Allied bombardment.’ That sort of thing.”

He smiled faintly.

“That’s not wrong,” he said. “They did the heavy lifting. I just pulled a lever and moved some wires.”

She leaned forward, eyes sharp.

“You did a little more than that,” she said. “Don’t you dare minimize it because you’re afraid of what it means.”

He blinked.

“What does it mean?” he asked.

She sat back.

“That you did something nobody else could,” she said simply. “Not because you’re perfect. Not because you’re whole. Because you were willing.”

He swallowed.

The patch itched.

For the first time since he’d woken up, he reached up and lifted it, letting the cool air touch the scarred eyelid beneath.

He kept the ruined eye closed.

The world stayed half-dark on that side.

He turned his head, looking at Kincaid with his one good eye.

“You know what they called me,” he said. “Out there.”

“A nuisance?” she suggested.

He huffed a laugh.

“One-eyed scout,” he said. “Like a joke. Half a pair. Half a man.”

She shrugged.

“Funny,” she said. “From where I’m sitting, it looks like you saw twice as much as anyone else.”

He snorted.

“That’s terrible, ma’am,” he said.

“I’m out of good lines,” she said. “Used them all on the colonel.”

He grew serious.

“Do you think they’ll remember it?” he asked. “The men who got out?”

“Every time they close their eyes,” she said. “Every time they hear a siren or a gate creak. Every time they roll over and there’s a real mattress under them instead of planks.”

He stared at the ceiling.

“I don’t want medals,” he said.

“You’re getting one,” she replied. “Probably more than one.”

“I don’t want my name on a plaque,” he said.

“Then we won’t hang it in your room,” she said. “We’ll put it in a hall somewhere, so strangers can argue about the details.”

He smiled.

“What do you want, then?” she asked quietly.

He thought.

“Permission,” he said.

“For what?”

“To keep being a scout,” he said. “Even with one eye. Even when it makes other people uncomfortable. To go where it’s gray and messy and try to make it a little less awful.”

She nodded slowly.

“I can do that,” she said. “At least in the part of the army I run.”

She stood.

“Get some rest, Daly,” she said. “You’ve got a lot of people to pretend you don’t recognize at the celebration tomorrow.”

“Celebration?” he groaned.

“They’re bringing in some of the men from the camp,” she said. “The ones well enough to travel. There’s talk of speeches. Maybe a band.”

He winced.

“That sounds worse than the culvert,” he said.

She laughed.

“Heroism comes in many forms,” she said. “You can face a microphone. You faced worse.”

She reached the door.

“Major?” he called.

She turned.

He hesitated.

“Thank you,” he said.

“For what?”

“For arguing,” he said. “When it got serious. When you could’ve just said, ‘No’ and slept easier.”

She held his gaze.

“You gave me a chance to be the kind of officer I wish I’d had when I was your age,” she said. “I wasn’t going to waste it.”

She left.

He lay there, listening to the distant rumble of trucks and tired voices.

He thought about the men pouring through the gap in the gate.

He thought about the sergeant.

About the way he’d squared his shoulders and said, “We’ll play your crazy hand.”

He was asleep before he realized he was smiling.

Years later, when the war was a story people told in pubs and classrooms, someone would ask a white-haired man at a Legion hall in Winnipeg:

“Is it true? That one scout freed fifty thousand Canadians in six hours?”

The man—Sergeant Thomas Price, retired—would sip his beer and shake his head.

“No,” he’d say. “It took all of us. Took every man who ran when the sirens screamed. Took every driver who kept the trucks running. Took every officer who decided to risk their career instead of writing another letter home.”

He’d pause, eyes drifting to a framed photograph on the wall—black-and-white, grainy, of a young man in uniform with a patch over one eye, looking like he’d just gotten away with something.

“But,” Price would add, voice softening, “it’s also true that none of it would’ve happened without one stubborn scout who refused to let a missing eye stop him from seeing a way through.”

And somewhere, far from the speeches and the simplified stories, Corporal Owen Daly would be walking along a quiet riverbank, listening to the water, the wind, the ordinary sounds of a world that had finally stopped screaming.

He would pause sometimes when he heard a distant siren—ambulance, fire engine, some city noise that meant help instead of danger.

He’d smile and shake his head.

“Still working, then,” he’d murmur.

One eye on the world.

Both eyes, in a way, always on the wire.

THE END

News

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare Rifles, Ignored His Own Commissar’s Orders, and Turned One Hill Into a “Forest of Ghosts” That Killed 225 Attackers and Broke the Siege

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare…

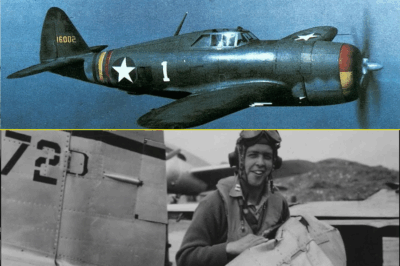

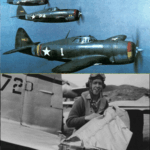

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That Weight Into a Weapon and Sent 3,752 Luftwaffe Fighters Plummeting From the Sky

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That…

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion, Claimed Ninety-Six Enemy Combatants Without a Single Direct Shot, and Sparked One of the War’s Most Tense Command Arguments

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion,…

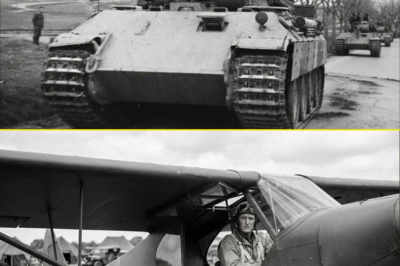

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane, Dove Through Fire, and Knocked Out Six Panzers to Save 150 Men

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane,…

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to Notice — But What He Saw, What He Asked, and the Argument That Followed Changed the Boy’s Entire Life Forever

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to…

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet Single Dad Janitor Stood Up, Walked to the Defense Table, and Changed Everything

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet…

End of content

No more pages to load