When Patton Rolled Into Messina First, Churchill Put Down His Cigar, Reached for the Right Joke, and Turned a Touchy Anglo-American Rivalry Into Ammunition for Winning the Bigger War

The telegram arrived in the middle of the afternoon, when London’s sky was the color of old tin and the air in the Cabinet War Rooms tasted of paper, smoke, and worry.

Winston Churchill sat at the head of the long table, waistcoat straining slightly, a fresh cigar smoldering between his fingers. Around him, maps covered the walls and the table itself—a patchwork of North Africa, Italy, and the long, jagged boot of Europe. Sicily lay there like a kicked stone in the water, almost—but not quite—touching the mainland.

They were in the middle of yet another discussion about shipping, landing craft, and the endless question of “what comes next” when an aide stepped quietly into the room.

“Prime Minister,” the young officer said, standing very straight despite the heat, “an urgent signal from General Eisenhower’s headquarters.”

Churchill turned his head, his eyes brightening with a mixture of curiosity and impatience.

“Well then, don’t let it stand there looking important,” he said. “Bring it to me before it dies of shyness.”

A faint ripple of chuckles moved around the table. The aide hurried forward and placed the flimsy sheet beside Churchill’s elbow. The Prime Minister picked it up, peering at the tight lines of type through his glasses.

His gaze flicked quickly across the words.

Then it stopped.

Then it went back.

Eisenhower’s message was brief, efficient, and utterly explosive in its implications:

MESSINA OCCUPIED STOP

THIRD U.S. ARMY ELEMENTS ENTERED CITY FIRST STOP

BRITISH EIGHTH ARMY ARRIVING SHORTLY STOP

ENEMY WITHDRAWAL ACROSS STRAIT CONTINUES STOP

OPERATION IN SICILY SUCCESSFULLY CONCLUDED STOP

For a heartbeat, the room seemed to hold its breath. No one else had read the signal, but they were watching Churchill’s face with the practiced attention of men who knew how much the tilt of an eyebrow could mean.

Churchill read it again, slower this time.

Messina.

Taken.

By Patton.

First.

He exhaled through his nose, a small cloud of cigar smoke curling upward.

“So,” he said softly, more to himself than anyone else. “The race is won.”

Across the table, General Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, cleared his throat.

“Good news, surely,” Brooke said. “Sicily in our hands. The enemy driven off the island. A success by any measure.”

“Oh, it is good news,” Churchill said, eyes still on the telegram. “Very good news indeed. Sicily is the key to the next door. We have unlocked it.”

He set the paper down, his finger tapping once on the word MESSINA.

“But,” he added, “it will not escape notice—particularly in certain quarters—that the first units into Messina wore American uniforms and followed General Patton’s flag.”

The room absorbed that in silence.

Everyone there knew about the unspoken contest that had been brewing between the British Eighth Army under General Bernard Montgomery and the American Seventh Army under General George S. Patton Jr. Both men were aggressive, ambitious, and very aware of how history might one day remember the campaign.

Messina, perched at the northeastern tip of Sicily, had become more than a city.

It was a finish line.

And now, it seemed, Patton had broken the tape first.

“Well,” Brooke said carefully, “Montgomery will not be… delighted.”

“No,” Churchill replied. “Monty will not be delighted at all.”

He looked up suddenly, his gaze sweeping the room.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “let us adjourn this meeting for a short while. I must consider how best to respond to this very welcome, very delicate piece of news.”

His tone carried both a smile and a warning.

He pushed back his chair and stood, adjusting his waistcoat with a small grunt. The ministers and officers around the table rose with him. As he moved toward the door, he gestured for one man to follow.

“Anthony,” he said, nodding toward Anthony Eden, the Foreign Secretary. “Walk with me.”

The two men moved down the narrow corridor of the underground complex, their footsteps echoing faintly off the concrete walls. The war rooms always felt like the inside of a ship that had been buried under London, Churchill thought—a vessel carrying the government through a storm no one had ever seen before.

Eden waited until they were alone, then spoke in a low voice.

“You’re thinking of the Americans,” he said. “And the British. And who gets which line in the newspapers.”

“I am thinking,” Churchill replied, “about how to keep this alliance stitched together tightly enough to strangle our enemy.”

He puffed on his cigar.

“Sicily is a triumph,” he went on. “It proves that our combined armies can leap from shore to shore and drive the enemy out. But men are still men, and generals are still the noisiest sort of men. Patton will be feeling ten feet tall tonight. Montgomery will feel as if someone has kicked his chair out from behind him.”

Eden gave a faint smile. “You did encourage Monty to see Sicily as a stage on which to show British leadership.”

“I did,” Churchill said. “And I do not regret it. But I also encouraged the Americans to take their share of the load—and credit. Now fate, in its usual mischievous way, has handed Patton the spotlight for the last act of this particular play.”

They reached a small side room with a desk, a couple of chairs, and a map of the Mediterranean on the wall. Churchill went in and shut the door behind them.

He lowered himself into the chair behind the desk, the springs protesting. Eden sat opposite.

“For all his faults,” Churchill said, “Patton is a fighter. He charges where others debate. The Americans admire that. Many of their soldiers adore him.”

“Many British officers don’t,” Eden noted dryly.

Churchill grunted.

“Montgomery,” he said, “is like a chess player who believes the game is won before the pieces are fully deployed. He likes to be certain, to polish every plan. It gives him confidence. But the Americans have a different instinct. They will take a chance where we would write another memorandum.”

He looked at Eden.

“And now,” he said, “Patton’s chance has paid off. His army has raced up the north coast and beaten Monty to Messina.”

Eden tilted his head thoughtfully.

“Do you suppose,” he asked, “that this matters more to us than it should?”

Churchill let out a low chuckle.

“My dear Anthony,” he said, “I live in a world where a single photograph—Patton standing in Messina’s square, his flag waving over some battered town hall—can carry more weight with the American public than fifty communiqués about ‘combined operations.’”

He leaned forward, the ember of his cigar glowing.

“Make no mistake,” he continued. “I want that photograph. I want it in every paper in New York and Chicago. I want American mothers to look at it and think, ‘Our boys are charging through Europe with British comrades at their side.’”

“And what do you want British mothers to think?” Eden asked.

“I want them to think,” Churchill said, “that their sons are marching beside the largest, most energetic ally their island has ever known—and that together we will finish this business.”

He sat back, brows knitting.

“But I must also manage the egos of the men who lead those sons. That means I must decide, very carefully, what to say about Patton’s victory.”

Eden studied him.

“So what will you say?” he asked.

Churchill took the cigar from his mouth, examining the ash.

“I will say,” he murmured, “that the American army has shown great dash and vigor in Sicily—and that the British army has shown steady, relentless pressure. That together they have forced the enemy to run, and that the race which truly matters is not to Messina, but to Berlin.”

He smiled suddenly, a glint of mischief appearing.

“And I might,” he added, “allow myself a small joke at Monty’s expense. He must not imagine himself immune.”

“Something gentle, I hope,” Eden said.

“Gentle,” Churchill said, “but not too gentle. The British Army has not come all this way to be treated like a piece on one man’s board. Patton’s success will remind everyone—including a certain Field Marshal—that the Americans are not here merely to hold our coats.”

He stubbed out the cigar decisively.

“Come,” he said, rising. “Let us go back and decide how to tell the world that the race for Messina has been won by the side that matters most: the Allied side.”

The next morning, the War Rooms buzzed with fresh reports.

Messina firmly occupied.

Axis forces withdrawing across the narrow Strait of Messina under fire.

British and American units shaking hands in the city streets, their faces tired and grinning, the rubble around them bearing the scars of bombardment.

Churchill had already drafted a message to Eisenhower, congratulating him on the success of Operation Husky. The wording had been precise: praising the “bold advances of the American forces” and the “tenacious drive of the British Eighth Army,” binding them together in a single phrase.

Now, as he sat with a fresh cup of tea, an aide arrived with yet another telegram.

“From General Alexander, Prime Minister,” the aide said. “On the ground in Sicily.”

Churchill nodded for him to proceed.

Alexander’s report summarized the situation on the island, then added a line that was more human than operational:

PATTON IN HIGH SPIRITS STOP MONTGOMERY COOL BUT DETERMINED STOP BOTH CLAIM CITY FOR THEIR MEN STOP RECOMMEND STRONG PUBLIC STATEMENT STRESSING JOINT ALLIED ACHIEVEMENT STOP

Churchill smiled.

“Of course they both claim it,” he said. “Two roosters, one perch.”

He turned to the group gathered around the table—Brooke, Eden, and a few other key ministers.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “it seems we must now perform a small balancing act for the benefit of our military poultry.”

Eden raised an eyebrow. “How do you propose to do that?”

Churchill took up his pen and pulled a blank sheet toward him.

“First,” he said, “I shall send a private message to Alexander to be passed on to both commanders. Something along the lines of—”

He began to write, speaking the words aloud as they flowed:

TO: GEN. ALEXANDER

PLEASE CONVEY MY HEARTIEST CONGRATULATIONS TO BOTH EIGHTH ARMY AND SEVENTH ARMY ON THEIR MAGNIFICENT ACCOMPLISHMENT STOP

THE AMERICAN ADVANCE TO MESSINA SHOWS GREAT DASH AND ENTERPRISE STOP

THE BRITISH ADVANCE SHOWS ENDURING RESOLUTION AND SKILL STOP

IN THIS RACE BOTH TEAMS HAVE WON THE ONLY PRIZE THAT MATTERS STOP

SICILY IS OURS AND THE ROAD TO ITALY LIES OPEN STOP

He paused, then added, almost as an afterthought:

TELL MONTGOMERY THAT EVEN THE FINEST JOCKEY CANNOT COMPLAIN WHEN HIS PARTNER IN THE NEXT STABLE WINS BY A NOSE STOP

TELL PATTON THAT HE HAS GIVEN THE ALLIED CAUSE A SPLENDID STORY BUT THAT THE BEST CHAPTERS ARE STILL TO BE WRITTEN STOP

Brooke gave a grunt that might have been approval.

“That should keep them both suitably proud and suitably reminded,” he said.

“But what about the House of Commons?” Eden asked. “And the press? They will want to know who got to Messina first.”

Churchill’s eyes sparkled.

“Ah, yes,” he said. “What shall we tell the House?”

He set the pen down, steepling his fingers.

“We shall tell them the truth,” he said. “But we shall choose which truth to emphasize.”

He looked at Brooke.

“Bernard has told me many times,” Churchill said, “that speed must never be purchased at the cost of care. He will have moved as he thought best. Patton, on the other hand, treats caution the way a bull treats a red flag.”

A few smiles appeared around the table.

“I intend,” Churchill continued, “to say something like this: ‘The Americans, led by General Patton, have shown extraordinary dash by reaching Messina with great speed. The British Eighth Army has pressed the enemy continually and forced him up the island. Between them, they have turned Sicily from a base of enemy operations into a springboard for our own.’”

He took a sip of tea.

“And when someone inevitably asks, ‘But Prime Minister, who won the race?’…”

He set down the cup and smiled like a man who had just seen the punch line before anyone else.

“I shall say,” he went on, “‘It seems that on this occasion, the Americans have won the cup. I am perfectly content that they should carry it—provided it is engraved with the words Victory for All the Allies.’”

Eden chuckled.

“That will play well in Washington,” he said. “And in London, too, I think.”

“It had better,” Churchill replied. “Because we shall need American goodwill and American steel for many more races yet.”

Two days later, Churchill stood at the dispatch box in the House of Commons, the green benches crowded, the atmosphere humming with anticipation.

Members leaned forward as he spoke of Sicily: of landings under fire, of hard fighting in the hills, of the enemy’s retreat.

“And now,” Churchill said, his voice filling the chamber, “the campaign in Sicily has reached its splendid conclusion. The city of Messina is in Allied hands. British and American soldiers stand together on that ancient shore, having swept the enemy from the island.”

A murmur of approval rippled through the House.

He went on.

“The American Seventh Army, under General Patton, executed a bold and rapid advance along the northern coast, reaching Messina with remarkable speed. The British Eighth Army, under General Montgomery, engaged the enemy steadily and drove him northward across rugged ground.”

He let the words hang for a moment.

“In this operation,” Churchill continued, “each has performed according to national character: the one with dashing vigor, the other with unyielding persistence.”

Laughter rustled through the benches, good-natured rather than mocking.

Then came the question he had been expecting, from an opposition member with a sharp mind and a fondness for headlines.

“So, Prime Minister,” the man called out, “do you admit that the Americans have beaten us to Messina?”

A ripple of tension ran through the chamber.

Churchill leaned forward, his hands resting on the sides of the dispatch box, his eyes glittering.

“I will gladly admit,” he said, “that on this particular occasion, the Americans have been first to a particular town. I offer them my hearty congratulations on winning what some may call a race.”

He paused, then added, his tone turning firm:

“But I must also remind the House that the only race which concerns His Majesty’s Government is the race to complete victory. If, in the course of that greater struggle, our Allies outpace us to a few milestones, I shall cheer them on—so long as we all reach Berlin together.”

For a heartbeat, there was silence.

Then the chamber erupted in applause and laughter, a wave of approval washing over him.

Churchill nodded once, satisfied.

Somewhere across the ocean, when the words reached them, American readers would smile, feeling seen and appreciated.

Somewhere closer, British officers would chuckle, knowing their Prime Minister had defended their honor without picking a needless fight.

And somewhere in Sicily, two generals—one British, one American—would read the carefully chosen phrases and hear, beneath the humor, the message intended for both:

You are both valuable. You are both watched. You are both part of something larger than your own glory.

Months later, long after the dust of Sicily had settled and the war had moved on to Italy and beyond, Churchill would recall that moment when Patton won the race to Messina.

He would remember the telegram in the smoky room, the quick flicker of wounded pride on behalf of his own army, the temptation to defend one side more fiercely than the other.

And he would remember what he had chosen to say instead.

He had chosen to praise Patton’s speed without slighting Montgomery’s method.

He had chosen to make a joke of the rivalry, not a rupture.

He had chosen to remind both his own people and the Americans that the prize at stake was not a city in Sicily, but a peaceful future in Europe.

In private, with his trusted circle, he had summed it up in a line that never quite made it into the official records, but stayed in the memories of those who heard it.

“In Messina,” he had said, “the Americans have won the race. Good luck to them. Let their generals collect trophies, so long as together we collect the end of this war.”

That was what Churchill really said, in his own way, when Patton rolled into Messina ahead of everyone else.

He said:

Well done.

Be proud.

But remember—the finish line lies far beyond that port, and we intend to cross it side by side.

THE END

News

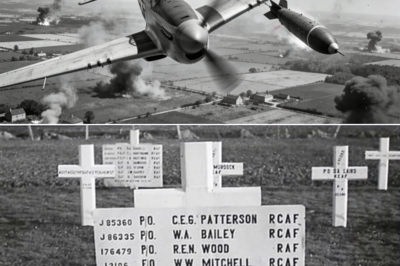

Out of Bullets, Out of Time: How a Tired Fighter Pilot Faced a Racing Flying Bomb Over a Sleeping City, Dared to Touch Its Wing With His Own, and Turned an “Impossible” Mid-Air Flip Into a Lifesaving Last Resort

Out of Bullets, Out of Time: How a Tired Fighter Pilot Faced a Racing Flying Bomb Over a Sleeping City,…

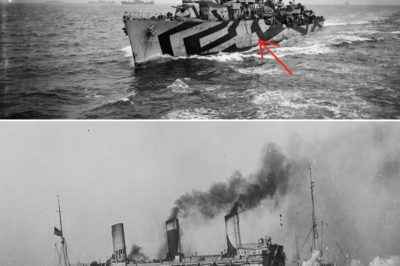

How A Half-Forgotten Harbor Painter Covered Gray Warships in Wild Stripes, Turned the Atlantic Into a Floating Gallery of Optical Illusions, and Left U-Boat Commanders Squinting Through Their Periscopes at “Modern Art” They Couldn’t Shoot Straight

How A Half-Forgotten Harbor Painter Covered Gray Warships in Wild Stripes, Turned the Atlantic Into a Floating Gallery of Optical…

From Laughingstock to Lifeline: How One “Backwards” Parachute Hack Turned a Ridiculed Tinkerer Into the Only Man Who Could Drop Through Hurricane Winds, Land Behind Enemy Lines, and Save an Entire Airborne Mission From Disaster

From Laughingstock to Lifeline: How One “Backwards” Parachute Hack Turned a Ridiculed Tinkerer Into the Only Man Who Could Drop…

From Slapped Helmets to Midnight Rescues: Fifteen Times George S. Patton Shocked Winston Churchill, Shattered Expectations, and Forced Britain’s Wartime Lion to Admit the Loud American Cavalryman Was Exactly the General the Allies Needed

From Slapped Helmets to Midnight Rescues: Fifteen Times George S. Patton Shocked Winston Churchill, Shattered Expectations, and Forced Britain’s Wartime…

The Night Eisenhower Quietly Admitted That Patton’s Hard-Charging Columns Had Turned the Enemy’s Own Lightning Tactics Against Them—and Explained Why Speed, Nerve, and Relentless Discipline Beat Even the Famous “Blitzkrieg” at Its Own Game

The Night Eisenhower Quietly Admitted That Patton’s Hard-Charging Columns Had Turned the Enemy’s Own Lightning Tactics Against Them—and Explained Why…

End of content

No more pages to load