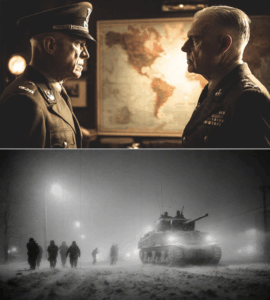

When Patton Drove His Tired Third Army to Bastogne First, Eisenhower’s Words Cut Through the Smoke, the Pride, and the Fury and Sparked the Most Tense Argument of Their War

Snow blew like ground glass across the parade field of the Luxembourg village, stinging faces and finding every loose button and seam. The sky hung low and gray, pressing down on the worn stone buildings and the crowd of American officers huddled inside the commandeered schoolhouse that now served as Eisenhower’s forward headquarters.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower stood at the front of the room, hands behind his back, jaw set. His face looked more like a tired small-town football coach in a worn uniform than the supreme commander of a vast alliance, but his eyes were sharp. On the crude maps pinned to the walls, red arrows and blue pencil marks showed the same thing: trouble.

The German counterattack had punched a swollen, jagged bulge into the Allied line in the Ardennes. Reports were still confused, distorted by bad weather, cut telephone lines, and air units grounded by clouds and fog. But one thing was clear: Bastogne was surrounded, and the enemy wanted to break through there.

The door opened with a rush of cold air and noise. General George S. Patton Jr. walked in like he owned the place, helmet under his arm, heavy coat dusted with snow, ivory-handled pistols at his hips. He nodded once at Eisenhower, then at the others.

“Sorry I’m late, Ike,” Patton said, voice loud in the cramped room. “Roads are a mess. Seems your war picked a fine time for winter.”

A few officers gave nervous half-smiles. Eisenhower did not.

“Sit down, George,” Ike said. “We’ve got work to do.”

Patton pulled out a battered chair and sat, posture still somehow aggressive. Around him were Omar Bradley, Courtney Hodges, and a scattering of staff officers whose names Patton did not bother to remember. A potbelly stove clanged softly in the corner, throwing out more smoke than heat.

Eisenhower tapped the map with a pointer.

“German forces have driven a salient through our lines here,” he said. “Their armored spearheads are pushing west. Their objective appears to be the Meuse. Bastogne sits on the road network they need. We have a parachute division and some tank destroyers in Bastogne. They’re surrounded.”

He looked at Bradley first.

“Omar, if Bastogne falls, what happens?”

Bradley rubbed his eyes. He hadn’t slept much in two days. “They get the road net. If they move fast enough, they could reach the Meuse before we can reorganize. That would split our armies, and then we’re in a real mess.”

Eisenhower nodded, then turned to Patton.

“George, how quickly can your army pivot north and attack to relieve Bastogne?”

The room went quiet. Several staff officers glanced at each other. They’d heard rumors that Patton had been planning for just such a contingency, that he’d kept options tucked away in his mind and on secret maps.

Patton leaned forward, eyes gleaming.

“In forty-eight hours,” he said.

The silence now had weight. One of Bradley’s staff colonels actually snorted before catching himself.

“Forty-eight hours?” Bradley repeated, eyebrows rising. “George, your army is driving east. Your units are spread out over—what—hundreds of miles? You’re facing stiff resistance. Your supply lines are stretched. You’re telling me you can turn your entire Third Army north and attack in two days?”

“Yes,” Patton said simply. “I’ll need priority on fuel and traffic control on the roads. I’ll need the engineers to keep those roads open. But if you give me those things, I will reach Bastogne and break the encirclement.”

Eisenhower watched him carefully. He knew Patton. He knew the bluff, the bluster, the pride—but he also knew the man’s habit of having the details worked out behind the theatrics.

“You’ve already drawn up plans,” Eisenhower said quietly. It wasn’t a question.

Patton allowed himself the smallest of grins.

“I had my staff prepare several contingency plans last week,” he said. “One of them was the possibility of a German counterattack through the Ardennes. My corps commanders are already rehearsed on the pivot north.”

Hodges shook his head in disbelief.

“You planned a major movement before we even knew this offensive was coming?” he asked.

Patton shrugged. “The enemy has a vote,” he said. “I just try to think like he does.”

Eisenhower placed both hands on the table.

“All right,” he said. “George, you have the mission. Attack north. Relieve Bastogne. That town must not fall. You’ll get priority for fuel and roads.”

Patton’s eyes flashed. “Yes, sir,” he said.

As Eisenhower moved on to details with the other commanders, Bradley leaned over and whispered, “George, you understand if you fail, every man lost on those icy roads is on your head.”

Patton whispered back without looking at him. “Omar, every man who dies in this war is on all our heads. The question is whether they die for something that matters.”

The snowstorm deepened as Patton’s columns turned north.

From the ground, the movement did not look like a neat arrow on a map. It looked like miles of vehicles coughing exhaust into the freezing air—tanks grinding through rutted roads, half-tracks sliding on ice, trucks stalled on hillsides until soldiers put their shoulders to the bumpers and shoved. It meant engines that refused to start in the morning and hands that stuck to metal. It meant tired drivers blinking ice from their eyelashes and infantrymen huddled in truck beds, wrapped in blankets, trying not to think about the men already fighting and dying in Bastogne.

Patton drove up and down the columns, leaning out of his jeep, calling to the troops. His scarf flapped in the wind; his helmet shone dull in the gray light. He could see it in their faces: fatigue, doubt, but also something else—trust. He’d driven them hard before, and they had come through. This was just another hard job, they believed, even if the snow tried to tell them otherwise.

At a crossroads, where military police struggled to untangle the mess of vehicles, Patton ordered his driver to stop. A young private in an MP helmet struggled to direct traffic, blowing into his whistle with little effect. A line of trucks sat motionless, while a tank destroyer crew cursed quietly as they tried to maneuver around a stuck ambulance.

Patton stepped out into the road.

“Who’s in charge here?” he barked.

The MP snapped to attention, almost dropping his whistle. “I—I am, sir. Private Thompson, sir.”

“Private, you are now the most important traffic cop in Europe,” Patton said. “These trucks are going to Bastogne. That means those men up there are holding on by their fingernails. You keep this road moving, or I swear I will personally come back and find out why not.”

Thompson swallowed. “Yes, sir.”

Patton clapped him on the shoulder—hard, but not unkindly.

“Good man,” he said, then turned to his staff. “Get some engineers here. Sand, chains, whatever they need. And food. These drivers will fight better if their bellies aren’t empty.”

As he climbed back into his jeep, his aide, Colonel Charles Codman, said, “You just ruined that boy’s sleep for the next twenty years.”

“I hope so,” Patton replied. “Maybe it’ll keep him alive, knowing what he’s fighting for.”

Inside Bastogne, the world had shrunk to snow, trees, and the constant, distant rumble of artillery.

The 101st Airborne Division and the units with them were dug into foxholes and cellars. The men knew they were surrounded. They knew they were short on food, short on ammunition, short on winter clothing. But they also knew the roads under their boots led everywhere—to the north, the south, the east, and the west of that part of Belgium.

“If we hold this crossroads,” one lieutenant told his platoon, “we choke the enemy in this sector. They need these roads more than we do.”

The men listened, breath steaming in the cold. They stamped their feet, blew into their gloves, watched the tree line. The idea of Patton’s army coming to help them was more rumor than reality, an echo passed from one shivering foxhole to another.

“Patton’s on the way,” a sergeant said, handing a cigarette to a soldier with chapped lips. “He’ll be here soon. You’ll see. Old Blood and Guts loves this sort of thing.”

The soldier took a drag and tried to smile. “He’d better,” he muttered. “Because I’m fresh out of enthusiasm for being surrounded.”

Back in Eisenhower’s headquarters, the mood was far from hopeful. Tension hung over the map boards like a second ceiling. The phones rang constantly. Runners came and went with messages, their boots thudding on the worn flooring. Outside, the weather kept the aircraft grounded, and snow muffled every sound.

Eisenhower stood with his chief of staff, Walter Bedell Smith, listening as a staff officer read the latest reports.

“German armored units continue to press west,” the officer said. “They’re meeting resistance, but the fog is giving them cover. Signals from Bastogne suggest they are under heavy pressure. Ammunition is low.”

“And Patton?” Eisenhower asked.

“His lead elements are still fighting their way up from the south,” the officer replied. “They’re making progress, but the roads are… challenging.”

“That’s one way to put it,” Bedell Smith muttered.

A British liaison officer cleared his throat.

“Sir,” he said to Eisenhower, “Field Marshal Montgomery believes we should perhaps consider a more deliberate response. He fears that throwing large forces into a hasty counterattack could lead to unnecessary losses.”

Eisenhower’s jaw tightened. He’d heard variations of this argument for days now. Go slow. Consolidate. Be careful. But he also knew what delay might mean for the soldiers in Bastogne and beyond.

“Tell Monty I appreciate his concern,” Eisenhower said evenly, “but the situation in Bastogne does not allow for leisurely consideration. If the town falls, the enemy gets the road net. That complicates everything.”

The British officer nodded, scribbling notes.

After he left, Bedell Smith said, “You’re putting a lot on Patton, Ike.”

Eisenhower stared at the map where Patton’s Third Army was represented by pins and colored lines.

“I know,” Ike said softly. “He thrives on this sort of challenge. My job is to make sure his courage doesn’t outrun our common sense.”

“And if he fails?” Bedell Smith asked.

“Then this bulge becomes a wound we’ll have to stop with even more blood,” Eisenhower replied. “But if he succeeds, we turn a crisis into an opportunity.”

He looked toward the frosted windows, out into the storm he couldn’t see.

“He asked for forty-eight hours,” Eisenhower said. “We’ll know soon enough whether his mouth wrote a check his army can cash.”

Patton checked his watch by the light of the dashboard as the jeep bounced along the frozen road. He could feel the passage of those forty-eight hours like a physical pressure.

“Sir,” Codman said, raising his voice over the engine noise, “Corps reports heavy resistance at the approaches to Bastogne. The enemy doesn’t want to give up the ring around the town.”

“Of course they don’t,” Patton said. “That’s what makes this fun.”

He said it lightly, but inside, he could feel a different kind of tension. He knew the cost already: broken trucks in ditches, tanks with frozen engines, soldiers whose names he would never know lying still in the snow. He kept his eyes forward, because if he looked back too long, he might hesitate—and that was a luxury he could not afford.

At the front, he climbed out of the jeep and stepped into a world of noise and white. Artillery boomed. Machine guns rattled. Smoke mingled with fog, turning everything into a shifting gray tapestry.

An infantry captain, face streaked with grime and snow, spotted him and hurried over.

“General Patton, sir,” the captain said, half shouting, half breathless. “Didn’t expect to see you this far forward.”

“You’re wrong,” Patton said. “You should always expect me where the fighting is hardest. How close are we to Bastogne?”

“On the far side of those woods,” the captain said, pointing with a gloved hand. “We’ve been pushing all morning. Enemy resistance is stiff, but they’re starting to pull back in places. Rumor is we’ve already shaken the noose.”

Patton nodded. “Rumor is a dangerous thing, Captain. Let’s give them facts instead.”

He turned to a nearby tank commander and slapped the side of the vehicle.

“Take your tanks through those woods,” Patton ordered. “Link up with the defenders in Bastogne. I want someone in that town who can tell Ike that Third Army got there first. Understood?”

“Yes, sir!” the tanker shouted.

As the tanks moved out, treads grinding into the frozen earth, Patton stood in the road, snow dusting his shoulders, watching. For a moment, the war narrowed to that simple vision: machines and men advancing, breaking through, making contact.

Hours later, in the gathering gray of afternoon, a radio operator in Patton’s headquarters tent jabbed a finger at his headphones.

“Sir!” he called out. “Message from the lead unit!”

The duty officer grabbed a pencil.

“Go ahead,” he said.

“Message reads,” the operator said, voice shaking with excitement, “‘We are entering Bastogne and have made contact with elements of the 101st. Route is open.’”

The tent erupted in cheers. Officers slapped each other’s backs. Someone whooped loud enough to make the lamp sway.

Third Army had reached Bastogne.

Patton, arriving minutes later, heard the noise before he stepped inside. When they repeated the message for him, he allowed himself a rare, open grin.

“Get that message to Eisenhower,” he said. “Word for word. And make sure he knows who did it.”

The phone on Eisenhower’s desk rang late that afternoon. Bedell Smith answered, listened, then covered the receiver with his hand.

“It’s from Patton’s headquarters,” he said. “Sir… they’ve made contact with Bastogne. The encirclement is effectively broken.”

The room seemed to exhale. A staff officer muttered, “Thank God.” Another leaned against the map board as if suddenly exhausted.

Eisenhower took the phone.

“This is Eisenhower,” he said.

The voice on the other end was crackling but excited.

“Sir, Third Army reports that their forward elements have entered Bastogne and linked up with the defenders. The road into the town is open. They request permission to continue pushing north to widen the corridor.”

Eisenhower’s shoulders sagged slightly. He hadn’t realized how tense they’d been until the wave of relief washed through him.

“Tell General Patton congratulations,” he said. “Tell him… tell him he did exactly what he said he would do.”

He hung up and looked around the room.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “Bastogne stands. Now the hard part begins.”

Later, when the immediate rush of decisions slowed and the phones were quiet for a rare few minutes, Eisenhower stood by the window, looking out at the snow-covered village. He could hear muffled shouts and laughter outside as word spread. The celebration was muted—no one forgot that men were still fighting and falling out there—but relief was real.

Bradley joined him at the window.

“George pulled it off,” Bradley said. “I’ll be damned.”

“You sound surprised,” Eisenhower replied.

Bradley shrugged. “I’m not surprised he did it,” he said. “I’m surprised he did it in time, in this weather, under these conditions. He drives his army like a racehorse. One day, that horse might break.”

Eisenhower’s mouth was a thin line.

“I need to talk to him,” he said. “Face to face. Before the legend grows bigger than the man.”

They met in a cold, drafty Belgian farmhouse that smelled of damp wool and wood smoke.

Maps were spread on the kitchen table, displacing the farmer’s plates and cutlery. A lantern swung gently from a beam overhead. Outside, trucks and jeeps came and went in a constant churn, their engines a low, persistent growl.

Patton arrived first, stomping snow from his boots. He removed his helmet and gloves but left his pistols on. He seemed energized, almost glowing, despite the dark circles under his eyes.

Eisenhower arrived shortly afterward, accompanied by Bradley and a small group of staff officers. He looked older than his years, lines etched deeper by the strain of the past week. But his gaze was clear.

“George,” Eisenhower said, stepping forward and extending his hand.

“General,” Patton replied, gripping his hand firmly. For a moment, they smiled at each other—not as caricatures on war posters, but as two men who had carried heavy burdens across continents.

Then Eisenhower’s smile faded. He gestured to the table.

“Let’s sit,” he said.

They gathered around. A draft crept under the door, lifting map edges and making candles flicker.

“I’ll say this plainly, George,” Eisenhower began. “You promised you’d reach Bastogne in forty-eight hours. You did it. That was a remarkable achievement. Your men did something here that will be studied for a long time.”

Patton’s chin lifted a little. “Thank you, sir,” he said. “Third Army was eager for the chance.”

Eisenhower looked at him steadily.

“And the cost?” he asked.

Patton frowned. “The cost is war, Ike. The cost is always high. But the cost of losing Bastogne would have been higher. The enemy needed that road hub. We denied it to them. Every man who fell on those roads died keeping this front from falling apart.”

Eisenhower’s voice remained calm, but there was a steel edge now.

“I’m not questioning the need for the attack,” he said. “I gave you the mission. You carried it out. But I’ve seen the casualty estimates. I’ve heard about trucks sliding off roads, men collapsing from cold and exhaustion, vehicles abandoned in ditches because there wasn’t time to pull them out.”

Patton’s eyes flashed.

“You didn’t call me here to congratulate me on my logistics,” he said. “You called me here to lecture me again about being too aggressive.”

Bradley shifted uncomfortably but said nothing.

Eisenhower folded his hands on the table.

“I called you here,” he said, “because today you may have saved this front—and I need to make sure that tomorrow you don’t destroy something else in the process.”

The words hung in the air like frost.

Patton blinked. When he spoke, his voice had dropped in volume but gained intensity.

“Destroy something else?” he repeated. “What do you think I am, Ike? Some sort of loose cannon who enjoys seeing his own men suffer?”

“I think,” Eisenhower replied slowly, “you are a battlefield commander with a gift I have never seen before. You see possibilities where others see obstacles. You move faster than our enemies expect. You scare them. You scare some of our own people. And that is both your greatest asset and your greatest danger.”

Patton leaned forward.

“My men didn’t march through that snow because they’re afraid of me,” he said. “They marched because they trust me. Because when I say we’ll get somewhere, we get there. Because they know when we attack hard enough, the enemy breaks faster and the war ends sooner.”

“And how many times,” Eisenhower asked quietly, “can you demand that level of sacrifice before there’s nothing left to push?”

The room seemed to shrink around them. Outside, a truck backfired. Inside, no one moved.

Patton’s jaw tightened.

“I didn’t come here to be scolded,” he said. “I came here thought I’d hear what you said about my army breaking that ring around Bastogne. I thought you’d be glad.”

Eisenhower’s reply came in a flat, even tone that carried more weight than any shout.

“Glad?” he said. “George, I am relieved. Deeply relieved. I am grateful. But I am responsible for every soldier in this theater, not just the ones in your army. And I am responsible for the political and strategic consequences of everything we do.”

He tapped the map with a finger.

“What you did here changes the situation radically,” Eisenhower continued. “You turned the German offensive into an overextended gamble. We’ll exploit that. But as we go forward, I have to balance the needs of the British, the Canadians, the French, and all the American armies. That means I cannot always give you everything you want. I cannot always let you charge ahead as far and as fast as you’d like.”

Patton’s temper, always close to the surface, flared.

“So this is about Montgomery,” he said. “About politics. About neat lines on a map. Meanwhile, my men prove what can be done in this weather, in this terrain, against this enemy, and you’re worried about hurting someone’s feelings?”

Bradley broke in, voice tight. “George, that’s not what he’s saying—”

Patton cut him off with a raised hand.

“No, let him say it,” Patton snapped. “Let him say what he thinks.”

Eisenhower didn’t raise his voice. He simply met Patton’s glare with a tired, unwavering stare.

“What I think,” Eisenhower said slowly, “is that if I unleashed you without restraint, you would drive all the way to Berlin with half the fuel you need and no sleep for your men, and you’d probably get there. But along the way, you would tear this alliance apart, and you might leave us so battered that we wouldn’t be ready for what comes after this war.”

Patton opened his mouth, then closed it again. The anger was still there, but so was something else: a flash of recognition.

“What comes after this war?” he asked, tone less sharp now.

“Rebuilding Europe,” Eisenhower said. “Preventing another conflict. Keeping our soldiers from becoming an occupying army that’s remembered only for the damage it caused. Every decision I make now has to be weighed against that future. Even when I order you to move faster. Even when I ask you to slow down.”

Patton looked down at his gloved hands, flexed his fingers, then stared at the map. When he finally spoke, his voice had lost its edge, but not its conviction.

“Do you know what those boys in Bastogne would have said if you’d told them to wait for a more tidy, politically balanced plan?” he asked.

Eisenhower gave a small, sad smile.

“I imagine they’d have said some very colorful things,” he replied. “And they would have been right to do so. That’s why I gave you this mission in the first place. Because I knew you were the one who could move fast enough.”

He leaned forward.

“But listen to me carefully, George. This is what I wanted to say to you, and I need you to actually hear it, not just react to it.”

The room seemed to hold its breath.

“You saved Bastogne,” Eisenhower said. “You did. Third Army did. No one can take that away from you. When people look back on this battle, they will see your name engraved on it. But mark my words: if you let pride drive you, if you let your fury outrun your judgment, history will remember you differently. It will say George Patton was a brilliant general who didn’t know when to stop. It will say he won battles but risked the larger cause.”

He paused, letting the words sink in.

“I won’t let that happen,” Eisenhower went on, voice still calm but now steely. “Not because I want to clip your wings. Because I need you. I need you alive, in command, and under control. I need you to keep doing what you just did—within the boundaries of a strategy that serves more than your own army.”

For a few seconds, the only sound was the wind whispering around the farmhouse.

Patton stared at him, eyes bright, throat working. When he spoke, his tone was low and forceful.

“You think I don’t understand the larger cause?” he asked. “You think all I see are arrows on maps and chances for glory? I know what this is about, Ike. I’ve seen what happens when war is mishandled. I’ve watched men die in previous wars because someone in the rear didn’t have the courage to push when it mattered.”

He jabbed a finger at the map.

“What we did here… this is the right kind of risk,” he said. “We bled to keep that town out of enemy hands. We bled to stop this offensive before it could grow. If you’d kept a tighter leash on me—if you’d waited for some perfect, balanced plan—how many more graves would be in that snow right now?”

Eisenhower nodded slowly.

“You’re right,” he said. “This risk was necessary. You were the right man to take it. That’s why I didn’t stop you. That’s why I’m not scolding you for what you just accomplished. I’m warning you about what comes next.”

He glanced at Bradley, then back at Patton.

“From this point on,” Eisenhower continued, “every success you have will make people more nervous. Not just our allies, but our own leaders back home. You’ve already been on thin ice before with your behavior. There are people in Washington who would be happy to see you stumble so they can say they were right about you.”

Patton’s mouth twisted. He knew that was true, and it stung more than any enemy bullet.

“So here is what I’m telling you, George,” Eisenhower said. “And I’m saying it as plainly as I know how.”

He leaned closer, his words slow and precise.

“You have just proven that, when the chips are down, you can move an army like no one else. Today, you turned a disaster into a turning point. For that, I will praise you publicly without reservation. I will tell everyone that you saved Bastogne. But behind closed doors, between you and me, I’m telling you this: I will not let you win this war in such a way that we cannot live with the peace.”

Patton blinked. “Meaning what, exactly?”

“Meaning,” Eisenhower said, “I will back your bold moves when they serve the bigger picture. And I will stop you cold when they don’t. Meaning I will fight for your reputation when you’re attacked unfairly—but I will also be the one who pulls you aside and says, ‘Enough,’ when you go too far. Meaning that when history asks me about George Patton, I want to be able to say: ‘He was the man who got to Bastogne first and helped save our line—but he was also the man who learned when to rein in his temper and serve something larger than himself.’”

The words landed like hammer blows. The argument, which had risen and fallen like artillery fire, narrowed now to this final exchange.

Patton stared at Eisenhower for a long moment. In that gaze was pride, hurt, admiration, and an understanding he didn’t particularly like—but could not deny.

“So that’s what you’ll say,” Patton murmured. “When they ask you later, that’s what you’ll tell them I was.”

Eisenhower’s answer was quiet but firm.

“I’ll say,” he replied, “that when George S. Patton turned his army in the snow and reached Bastogne first, he reminded us what determination and courage can do. And I’ll say that in that moment, I knew I had to protect him from his enemies and from his own worst impulses, because we needed his fire—but not a wildfire.”

Patton’s shoulders dropped just a fraction. Some of the coiled energy seemed to leave him. He let out a breath that clouded in the cold air.

“You always were better with words, Ike,” he said, half growling, half amused. “I prefer simple orders.”

Eisenhower allowed himself a small smile.

“Then here’s a simple order,” he said. “Keep pressing where I tell you to press. Keep outrunning the enemy, not your own support. Keep frightening them, and I’ll do my best to keep everyone else calm.”

The tension in the room finally loosened. Bradley shifted, the staff officers glanced at each other, shoulders unwinding.

Patton pushed back his chair and stood.

“Very well,” he said. “I’ll keep doing my job. You keep doing yours. And when this is over, we’ll let history say what it will.”

He hesitated, then added, “But no matter what anyone writes later, remember this, Ike: those boys up there in Bastogne won’t forget who came for them in the snow.”

Eisenhower stood as well, looking him directly in the eye.

“Neither will I,” he said.

He extended his hand again. Patton stared at it for a second, then took it. Their grip was firm, not just in respect, but in something approaching mutual understanding.

For a moment, the argument, the pride, the strategy, the politics—all of it fell away, leaving only two men who had grown up in the same army, shaped by the same wars, now trying to steer a storm big enough to drown them both.

Outside, the engines kept rumbling. The snow kept falling. In the distant dark, Bastogne still held, now linked by a fragile, hard-won corridor to the rest of the Allied line.

As Patton left the farmhouse and walked back toward his jeep, Codman fell into step beside him.

“Sir,” Codman said carefully, “if I may ask… what did General Eisenhower say to you?”

Patton paused, looking out toward the north, where his tanks and troops still strained toward the enemy.

“He said,” Patton replied after a moment, “that I reached Bastogne when I said I would—and that he’s going to spend the rest of this war making sure I don’t reach beyond where I should.”

Codman considered that.

“And how do you feel about that, sir?”

Patton’s breath steamed in the cold. A faint, crooked smile tugged at his mouth.

“I feel,” he said, “like a racehorse that’s just been reminded there’s a finish line, not just a track. Now let’s make damn sure we win the race.”

He climbed into the jeep, gave a sharp nod, and the vehicle rolled out into the snowy dusk, heading back toward the front—not just to prove himself, but, in some newly acknowledged way, to prove Eisenhower right about why he had been unleashed in the first place.

Behind him, in the farmhouse, Eisenhower returned to the maps. He marked the new positions around Bastogne, lines tightening, enemy arrows bending back. He thought about what he had just said, and what he would someday say when people asked him about that winter.

He knew the words he would use for Patton: brave, relentless, brilliant, difficult—and necessary.

He also knew what he would say about his own role.

“I did what I had to do,” he would say. “I gave George Patton the chance to perform his miracle in the snow. And then I made sure that miracle fit into a victory bigger than either of us.”

Outside, over Bastogne and the surrounding forests, the clouds were beginning to thin. Soon, the planes would fly again. The war would move on, rolling eastward toward its final act.

But the memory of that moment—of Patton’s army turning north, of Bastogne holding, of Eisenhower’s quiet, cutting words in that chilly farmhouse—would remain, long after the snow melted and the maps were cleared away.

THE END

News

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her Laughed—Until the Screen Changed, and the Truth Sparked the Hardest Argument of His Life

When the Young Single Mom at the ATM Whispered, “I Just Want to See My Balance,” the Millionaire Behind Her…

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind the $600 Million Deal That Was About to Decide Every One of Their Jobs and Futures

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind…

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the Millionaire in Line Behind Him Heard Everything—and What Happened Next Tested Pride, Policy, and the True Meaning of Help

When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the…

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up a Doll, Looked Under the Bed, and Uncovered a Hidden “Secret” That Nearly Blew the Family Apart for Good

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up…

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really on His Plate and the Argument That Followed Changed Everything About What He Thought Money Could Buy

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really…

He Built a Fortune and Forgot His Family—Then His Aging Father Lived in Quiet Pain Until the Day He Caught His Own Wife Sneaking Out and Discovered the Secret That Changed All Their Lives Forever

He Built a Fortune and Forgot His Family—Then His Aging Father Lived in Quiet Pain Until the Day He Caught…

End of content

No more pages to load