When an Ammunition Ship Vanished in a Flash Over Guadalcanal, 250 Men Died in Seconds—Decades Later, One Sailor’s Hidden Journal Reignited the Fierce Debate Over What Really Blew Up USS Serpens and Why No One Remembered

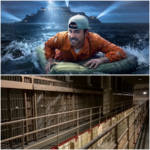

On a January night in 1945, the sky over Guadalcanal split open.

Men on the beach would later say it was as if someone had dragged a match across the stars—one long, blinding streak of white—and then torn the darkness in half with a roar that swallowed every other sound.

By the time the echo died, the USS Serpens (AK-97) was gone.

No burning hulk. No struggling silhouettes in the water. Just a widening cloud of smoke and glowing fragments tumbling out of the sky, hissing as they struck the sea.

For years, that was all anyone seemed to remember: a flash, a boom, and a name carved into a stone at Arlington.

But the real story didn’t end with the explosion.

It ended seventy-five years later, with a worn notebook, a family that refused to stop asking questions, and an argument that finally became too serious—and too loud—to ignore.

1. The Ammunition Ship

Seaman First Class Tommy Reyes had been on the Serpens for six months, and the smell of cordite never really left his nose.

He’d grown up in San Pedro, California, the son of a fisherman. To him, ships meant salt and diesel and fish scales stuck to boots. Now they meant crates of artillery shells, stacks of depth charges, and boxes stenciled with warnings in big black letters: HIGH EXPLOSIVE. HANDLE WITH CARE.

“Handle with care,” Tommy muttered under his breath, bracing himself as a sling of shells swung across the hold. “Sure. Like eggs. Except the eggs can take half the pier with ’em.”

“Quit talking to the ammunition, Reyes,” Chief O’Hara called from the hatch. “Creeps the new guys out.”

Tommy grinned up at the red-faced boatswain’s mate.

“You told me to treat it like family, Chief,” he said.

“I said respect it,” O’Hara replied. “I didn’t say tuck it in and read it bedtime stories.”

The Army stevedores in the hold laughed. Sweat ran down their necks in shiny tracks. Outside, the afternoon heat above Guadalcanal pressed on the ship like a hand on a lid.

The Serpens was moored off Lunga Beach, anchored out with a line of other service ships—oilers, tenders, floating warehouses feeding the endless appetite of the war grinding its way across the Pacific.

She was a converted cargo ship, a “Liberty” type with Coast Guard crew, stacked now not with flour and boots but with death in carefully counted boxes.

Tommy liked the ship. She was ugly, but she floated. She fed the front line. And, he told himself when the old fear crept up, she hadn’t blown up yet.

2. Orders and Arguments

That afternoon, Lieutenant Jack Harlow climbed the ladder from the main deck to the bridge with a face like a thundercloud.

The exec had the posture of a man who slept with a clipboard under his pillow. Neat, precise, cool. But today his jaw was clenched.

The captain, Commander Peters, was studying a chart at the wheelhouse table. Salt-and-pepper hair, coffee permanently in hand, the expression of someone who’d once enjoyed the sea and now mostly enjoyed getting through the day without a letter to next of kin.

“Harlow,” Peters said. “Tell me you’ve got good news.”

“Depends on your definition, sir,” Harlow replied. He held up a flimsy message form. “New orders from COMSOPAC. They want us fully loaded and ready to move in forty-eight hours.”

Peters’ brows rose.

“Forty-eight?” he said. “We’re halfway through loading as is.”

“Yes, sir,” Harlow said. “The Army stevedores say they can try twenty-four-hour rotations, but they’re already at the edge. Chief O’Hara’s asking for more safety checks, not fewer.”

Peters sipped his coffee, eyes narrowed.

“And the ammo depot?” he asked. “They still sending up those six-inch shells and depth charges together?”

“Yes, sir,” Harlow said, lips thinning. “Mixed loads per the supply schedule. I’ve… expressed concern.”

The captain snorted.

“You and every other skipper fueling this circus,” he said. “Look, Jack, you know the drill. Every time the front moves, the timetable goes crazy. They’re planning something up the line. And that means we pack like it’s Christmas Eve in a department store.”

Harlow stepped closer, lowering his voice.

“With respect, sir,” he said, “we’re an ammunition ship. You push the men too hard, we get careless. We’re one dropped crate away from lighting up half of Guadalcanal. I want written sign-off on any changes to standard loading procedures.”

Peters’ gaze sharpened.

“That a formal request, Lieutenant?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” Harlow said. “It is.”

The commander held his stare for a long beat.

“This war’s gonna be won by men who do their job,” Peters said softly. “Not by men who write memos.”

“With respect, sir,” Harlow repeated, voice cool, “part of my job is making sure my men don’t die because someone ashore wants a faster paperwork line.”

The air between them tightened. và cuộc tranh cãi trở nên nghiêm trọng và căng thẳng—the disagreement didn’t stay polite. It grew teeth.

Peters set his cup down with a sharp clink.

“You think I don’t know what we’re sitting on?” he snapped. “I’ve written enough letters, Jack. I remember every name. I’m not about to turn this ship into a roman candle because some staff officer is in a hurry.”

He jabbed a finger at the message.

“But those same officers sign our fuel chits,” he added. “They sign the requisitions that get your boys fresh bandages and boots. We push back so hard we fall off the map, they’ll find some other ship to carry the load next time.”

Harlow’s jaw worked.

“So we just… bend?” he asked.

“We bend,” Peters said. “We don’t break. You put your concerns in the log. I’ll respond in writing. That way, if anything does go sideways, future historians can have a field day blaming us both.”

He picked up his coffee again, a small, weary smile ghosting across his face.

“In the meantime,” he said, “double the safety briefings. No smoking on deck, no loose shells, no shortcuts. Tell O’Hara if he sees anyone cutting corners, Coast Guard or Army, he has my blessing to throw them over the side.”

Harlow exhaled.

“Aye aye, sir,” he said.

As he turned to go, Peters glanced out the bridge window at the powder-blue sky, at the faint smudge of jungle-green shoreline.

“And Jack,” he added quietly, “when this is over, remind me to never sign up for an ammunition ship again.”

3. Last Letters

That night, Tommy sat cross-legged on his bunk in the forward berthing, pencil in hand, paper propped against a cardboard box stamped SMALL ARMS.

Dear Mom,

Still somewhere warm. Still somewhere with coconuts. Still can’t tell you where. If the censors let this through, assume I’m not writing from Antarctica…

He paused, listening.

The ship creaked and hummed softly around him. Far off, someone strummed a guitar. The smell of coffee drifted down from the mess deck.

“Reyes,” a voice said from the next bunk. “Tell your mom they’re feeding us steak every night. Maybe the Coast Guard’ll get a better reputation.”

It was Ellis, another seaman, face half-hidden in the dim light.

“Yeah, right,” Tommy said. “Mom knows me. If I say steak, she’ll picture my face and know it’s lies.”

He wrote:

The guys still call this a “lucky ship” because she’s never seen combat direct. But we’re loading enough ammo right now to make our own battlefield if we’re stupid…

His pencil hovered.

He thought about the argument he’d overheard on deck earlier, raised voices drifting down through the open hatch. He hadn’t caught all the words, just the tone: tension, frustration, worry.

He could see Chief O’Hara chewing his mustache, talking about fuses. An Army sergeant complaining about shifts. The exec’s clipped voice, the captain’s low growl.

He chose his words carefully.

Don’t worry, though. The officers here are careful. Maybe too careful sometimes. We do nothing without three meetings and a safety brief…

He didn’t write about the crate that had slipped at sunset, swinging wild for a moment before the hoist crew recovered it, everyone’s hearts in their mouths. He didn’t write about the way his hands had shaken for ten minutes afterward.

You asked if I’m scared, he wrote instead.

I am. Everyone is, if they’re honest. But it’s a working scared, not a hiding-under-the-bed scared. We do the job. We pray the gear holds. We remember you’re home waiting…

The ship’s bell rang eight times far above: midnight. Another day ticked over.

Tommy signed the letter, folded it, and slid it into an envelope. He wrote “Reyes, Tom” and his APO address in block letters.

He didn’t know it, but a mail clerk would one day stamp “DECEASED” across that envelope and send it back.

4. January 29, 1945

The day of the explosion started like every other: hot, sticky, relentless.

By noon, the holds were a maze of crates and shells, neatly stacked. Men moved through the rows like ants in a tunnel, carrying, checking, stowing.

In the mess, coffee pots emptied and refilled in endless rotation. Somewhere on the beach, a baseball hit by a bored sailor sailed into a clump of palm trees, triggering a rain of angry birds.

Around mid-afternoon, Peters granted liberty to a portion of the crew. Not all. Never all—not on an ammo ship. But enough.

“Take four hours,” O’Hara told Tommy’s section. “Stretch your legs. Don’t do anything dumb enough to make me come find you.”

“Aye, Chief,” Tommy said, trying not to look as relieved as he felt.

On the Higgins boat into the beach, the men joked about warm beer and postcards and whether they’d finally get a USO show with decent music.

They spread along the sand road, some heading for the makeshift canteen, others for the little chaplain’s hut or the swimming area marked by a rope and a sign warning about sharks “that hadn’t gotten the memo about the ceasefire.”

By eight that night, they were heading back.

The sky was clear, the Milky Way a luminous river overhead. The sea was calm. The silhouette of the Serpens sat against the horizon, lights along her deck like a string of yellow beads.

Tommy sat on the edge of the boat, hands in his lap, the breeze blessedly cool on his face.

He thought about the letter he’d mailed that afternoon, slipping it into the canvas bag with a dozen others. He thought about home. About fish scales on the deck boards of his father’s boat. About the way the harbor smelled at sunset.

He didn’t see the first flicker.

No one did. Not really.

Later, some would say they saw a brief glow near the forward hold, like a match struck in a dark room. Others would swear they heard a sharp crack before the main explosion, as if something had snapped deep inside the ship’s steel bones.

What everyone remembered was the sound.

It wasn’t just loud. It was… total.

A white light erupted from the Serpens’ midsection, so bright it seemed to erase the ship’s outline for a heartbeat. There was no slow build, no series of small blasts. One moment, the vessel was there; the next, a giant white blossom filled the night.

The shockwave hit the boat like a giant hand, throwing men flat. The sound punched the air from Tommy’s lungs. For a second, he heard nothing at all—just a high, awful ringing.

When the boat steadied and the world came back in fragments, he pushed himself up and looked.

Where the Serpens had been, there was chaos.

Fireballs—small, compared to the first flash, but still enormous by any normal standard—rose from the water, exploding shells cooking off as they fell.

Chunks of steel, some the size of jeeps, arced through the air and splashed down. The night smelled of burned metal and something chemical and wrong.

“Jesus,” someone whispered hoarsely. “She’s gone.”

“Get down!” the coxswain yelled. “Get—”

Another blast, smaller, went off closer to the waterline. A geyser of spray drenched them.

Men on the beach ran to the water’s edge, silhouetted against the blooming fire. On the nearby shore installations, sirens wailed.

Tommy’s hands shook on the gunwale.

“Chief’s on board,” he said, his voice strange in his own ears. “Harlow. The stevedores. The cooks. They’re all—”

He couldn’t finish.

In the days to come, the official reports would say the explosion heard that night was “of such magnitude that few, if any, on board could have survived.”

They’d be right.

5. The Inquiry

War doesn’t stop because one ship disappears.

Within twenty-four hours, the ammunition depot prepared to shift loads to other ships. The Navy divers began to search the area where the Serpens had been anchored. Chaplains drafted condolence letters.

The Board of Inquiry convened in a clapboard building on Guadalcanal that smelled of paper, sweat, and mosquito repellent.

Harlow, spared by a twist of fate—he’d been ashore at a logistics meeting when the ship blew—sat at a table beneath a creaking ceiling fan, his dress whites already limp in the tropical heat.

Across from him, three officers: a Navy captain, a Coast Guard commander, and an Army colonel. Between them, a stenographer’s machine clacked steadily.

“For the record, Lieutenant,” the Navy captain said, “state your name, rank, and duty assignment on USS Serpens.”

“Harlow, Jack C., Lieutenant, United States Coast Guard,” Harlow replied. “Executive officer, USS Serpens, AK-ninety-seven.”

“You were ashore at the time of the explosion,” the Coast Guard commander said. “Correct?”

“Yes, sir,” Harlow said, fighting the reflexive flinch of guilt. “At the request of the base supply officer. We were finalizing load manifests for the—” He stopped, swallowing. “For the load we… never finished.”

The Army colonel tapped his pen.

“The board has reviewed your written comments in the ship’s log about loading procedures,” he said. “Do you stand by your assessment that ‘undue haste’ and ‘confusion in supply scheduling’ created additional risk?”

Harlow hesitated.

He could feel Peters’ eyes on him, even though the captain now sat further down the table, waiting his turn, face impassive.

“Yes, sir,” Harlow said. “I stand by it.”

The Navy captain’s jaw tightened.

“You understand,” he said, “that suggesting negligence in Army procedures is a serious charge.”

“I am not accusing anyone of negligence, sir,” Harlow said carefully. “I am saying that when you mix high explosives, fatigue, and unclear orders, risk goes up. I voiced those concerns up my chain of command.”

The Coast Guard commander flipped through a folder.

“Your captain acknowledged those concerns in writing,” he said. “He also states that all safety precautions were followed, that no deviations from standard ammunition handling procedures were authorized.”

“Yes, sir,” Harlow said. “On the ship, we followed procedure to the letter. Chief O’Hara made sure of it. The Army stevedore sergeants were just as strict.”

“Then how do you explain the… event?” the Army colonel demanded. “You say everyone did everything right. Yet the ship exploded like a bomb.”

Harlow’s hands curled into fists in his lap.

“Sir,” he said, “I don’t know. I wish I did. I wish we had more than fragments and memories.”

“That’s not good enough, Lieutenant,” the colonel snapped.

“And yet it may be all we have,” the Coast Guard commander said quietly.

The Navy captain drummed his fingers.

“There has been speculation,” he said, “about enemy action. A torpedo, perhaps. Sabotage. Did you see any indication—prior to the explosion—that an enemy submarine was in the area?”

Harlow thought of the calm water, the clear night, the sky turning white.

“No, sir,” he said. “We had no sonar contact. No alerts from destroyers. No reports of enemy aircraft.”

“Nonetheless,” the captain said, “for the sake of the families and the service records, it may be preferable to attribute this loss to enemy action.”

The sentence hung in the air.

“Preferable to whom?” Harlow asked before he could stop himself.

The colonel sat up.

“Lieutenant—” he began.

Harlow forged on, something in him snapping.

“With respect, sir,” he said, voice tight, “if this was an accident, if something went wrong with the ammunition or the handling, saying ‘oh, the enemy must have done it’ doesn’t fix that. It just… buries it.”

He thought of Tommy Reyes’ grin. Of Chief O’Hara’s barked laughter.

“And it doesn’t honor the men we lost,” he added. “They deserve the truth. Not a story that makes us feel better.”

The room went very still. The fan creaked overhead like an old man clearing his throat.

The Coast Guard commander regarded him for a long time.

“The truth,” he said at last, “may be that we don’t know. And may never know.”

He set down his pen.

“Let’s take a recess,” he said.

The board would ultimately write that the loss of Serpens was “presumably the result of an internal explosion, exact cause undetermined.” In some correspondence, it would be listed as “enemy action.” In others, “accidental explosion.”

The war moved on. Other ships blew up. Other men died.

And back home, families opened letters that said their sons had been “lost in the service of their country” without much more detail than that.

6. Names on Stone

In a corner of Arlington National Cemetery, not far from the rows of white markers that form such a neat, brutal geometry, there is a different kind of monument.

A long, low stone, carved with names. No bodies beneath. Just etched letters standing in for men whose remains were forever mingled with steel and sea and South Pacific sand.

USS Serpens, it says. January 29, 1945.

The names march down the stone. Coast Guardsmen. Army stevedores. A Public Health Service doctor. Young. Old. Italian surnames. Irish. Polish. Reyes, Thomas A.

On a humid July afternoon, seventy-five years after the explosion, a young woman traced that name with her fingers.

Lily Reyes had seen her grandfather’s name before—on a family tree, on an old photograph—but seeing it here was different. Here, it wasn’t just part of her history. It was part of the nation’s.

Her father stood a few feet away, hands in his pockets, staring at the skyline of D.C. beyond the trees.

“You okay?” he asked.

Lily nodded, swallowing.

“I just didn’t realize how many,” she said, eyes moving along the stone. “He always said ‘a lot of guys’ when he talked about the ship. I didn’t picture… all this.”

Her father’s gaze softened.

“He didn’t talk much about the explosion,” he said. “Just the funny stuff. The time they accidentally dropped a crate of potatoes into the admiral’s gig. The time the chief made them scrub the deck three times because someone flicked a cigarette butt near the hold.”

Lily smiled faintly, fingers still on the stone.

“He wrote about it,” she said.

Her father blinked.

“He what?”

“In his journal,” Lily said. “The one you gave me. From the war. I didn’t think it was much at first. Just lists. ‘Shift in hold #3.’ ‘Mail went out.’ But then the last few days…” She shook her head. “It’s like he knew something was wrong.”

Her father frowned.

“He never showed that to me,” he said.

“I don’t think he showed it to anyone,” Lily said. “I found it in a toolbox after Aba died. Between wrenches.”

A voice behind them cleared gently.

“Excuse me,” it said. “Sorry to interrupt.”

They turned.

A man in Coast Guard dress blues stood a respectful distance away. Late thirties, maybe forty, with a folder tucked under his arm.

“I couldn’t help overhearing,” he said. “You’re related to one of the Serpens crew?”

“Yes,” Lily’s father said. “My father. Tommy Reyes.”

The man’s face lit.

“Reyes,” he said. “Seaman First Class. Ammunition detail. I’ve read his name so many times in the casualty list I feel like I know it by heart.”

He stepped closer, extending a hand.

“Commander Jason Cole, U.S. Coast Guard,” he said. “I’m with the history office. We maintain records on ship losses. Serpens is one of mine.”

Lily shook his hand.

“You… study what happened?” she asked.

“Every scrap of paper I can get,” Cole said. “And lately, every scrap of… story. There’s a lot the official documents don’t say.”

Lily glanced at her father, then back.

“I have his journal,” she said.

Cole’s eyebrows climbed.

“You do?” he said. “From before the loss?”

“Yes,” Lily said. “The last entry is dated the day before the explosion.”

Cole drew a slow breath, as if he’d just heard someone say there was a fresh photograph from 1945.

“Would you…” he began, then stopped, catching himself. “I mean, if you were willing to share copies, that could be a huge addition to the story we can tell about these men. About what that last week was like for them.”

Lily heard the sincerity in his voice. She also heard the carefulness. The readiness for a no.

She thought of her grandfather at the kitchen table, older and rounder, telling silly stories about the war to keep the dark parts at bay.

“I think that’s why he wrote it,” she said. “Because there’s stuff he couldn’t say out loud.”

Her father nodded slowly.

“If it helps people remember him as more than a name on a stone,” he said, “I’m okay with that.”

Cole smiled.

“Then let me buy you both a coffee,” he said. “I’ll tell you what we know. And we’ll see how your grandfather’s words fit into the gaps.”

7. Paper and Ghosts

Two hours later, in a quiet corner of a café not far from the Pentagon, Lily slid the worn notebook across the table to Commander Cole.

It was small, the kind you could slip into a shirt pocket. The cover was stained and soft from handling. Inside, the pages were filled with neat block letters, dates at the top.

Cole opened it with the reverence of someone handling a relic.

“June 12, 1944,” he read. “Report aboard USS Serpens. Didn’t know Coast Guard had big ships like this. Thought we just rescued people in storms…”

He chuckled softly.

“He’s not wrong,” he said. “We did a lot of both, that war.”

He flipped forward, skimming.

“Here,” Lily said, pointing. “The January entries.”

He found the page.

January 26: Loading continues. Feels like the ship is swallowing the whole ammo depot. Chief says if someone sneezes wrong we’ll be a new constellation.

January 27: Exec had a blow-up with some Army officer about mixing stuff in the same hold. Chief walked by afterward muttering about fuses. Guys are making jokes, but everyone’s jumpy. I’m jumpy. Don’t tell Mom.

January 28: We almost dropped a crate today. Sling slipped. For a second I thought, “This is it.” Everything went slow, like the movies. Then the line held. Guys laughed after but it wasn’t a real laugh. I heard LT Harlow arguing with the captain again. Words like “undue risk” and “paper pushers.” Feels like everyone’s tired and mad and trying not to show it.

January 29: Got four hours on the beach. Wrote Mom. Water looked nice. The ship looked… normal. Like always. Funny how you can be sitting on a bomb and still joke about the coffee.

Cole read in silence for a while, lips moving faintly as he absorbed each line.

Finally, he closed the notebook gently.

“This is… incredible,” he said. “Not because it tells us exactly what blew the ship—that still might be beyond anyone’s reach—but because it shows what the men were feeling. The tension. The fatigue. The sense that something was off.”

He looked at Lily.

“Your grandfather mentions arguments between the exec and the captain,” he said. “There’s a note in the logs about concerns over loading speed. Harlow raised them formally. Peters responded. But neither of them say how angry it got. How… serious.”

“And the Army?” Lily’s father asked. “Did any of them write anything down?”

“Army records are spottier,” Cole said. “They lost officers in the blast too. The stevedores didn’t leave many diaries. But we do have letters from families saying they were told it was ‘enemy action,’ while the Coast Guard files lean toward ‘internal explosion.’ That discrepancy has… bothered people.”

“And you?” Lily asked. “What do you think?”

He took a deep breath.

“I think we put an extraordinary amount of explosive material onto a single hull, in a hurry, in conditions that were far from ideal,” he said. “We did it because the war demanded it. Because men on other islands needed shells more than we needed a leisurely loading schedule.”

He sipped his coffee.

“I also think there’s no evidence of a torpedo or an aerial bomb,” he added. “No radar contacts. No submarine reports. Just a ship that suddenly became a sun.”

“And the argument about what to call it?” Lily said. “Accident, enemy action, fate…”

“That argument,” Cole said, “has been going on in one form or another since 1945. On paper, in survivor reunions, in little side comments in memos. Some wanted enemy action because it felt… more meaningful. Easier to accept your son died in battle than in a paperwork mix-up. Others, like Harlow, pushed for honesty even if it hurt morale.”

He glanced at the notebook.

“Your grandfather’s words add weight to the side that says: the risk was real, and everyone knew it,” he said. “They weren’t careless. They were careful. But the system above them pushed that carefulness to its limits.”

Lily chewed her lip.

“So what do you do with that?” she asked.

Cole smiled ruefully.

“I get into arguments,” he said. “Serious, tense arguments, with people who think we should leave well enough alone. With people who say, ‘Why stir this up? It’s been decades.’ With others who say, ‘If you call it an accident, you disgrace the dead.’”

He spread his hands.

“But I also talk to families,” he said. “And most of them, when they hear what you’re hearing, say, ‘Thank you for not treating them like a footnote.’”

He folded his hands over the notebook.

“I’d like to quote this,” he said. “In an article. In a briefing. At the next memorial service. Your grandfather’s line about ‘working scared’ is exactly the kind of thing we forget about support ships. They weren’t in the newsreels. They were just… there. Until they weren’t.”

Lily nodded.

“Use it,” she said. “Just… make sure his name’s on it. Not just ‘an anonymous sailor.’ He deserves better than that.”

“He’ll get it,” Cole said.

8. The Wreck

A year later, Lily stood on the deck of a research vessel off Guadalcanal, peering down into water so blue it looked fake.

The air was hot, heavy with salt. The coastline curved away around them, a necklace of green hills and white beaches. Somewhere beyond the trees, the rusted skeletons of tanks and trucks lay where they’d been abandoned after another war.

Beside her, Commander Cole adjusted his headset.

“You sure about this?” he asked.

“No,” Lily said. “But I’m here.”

He grinned.

“That’s usually enough,” he said.

The joint expedition—Coast Guard historians, Navy divers, and Solomon Islands maritime archaeologists—had been Cole’s idea. For years, the exact resting place of the Serpens had been an approximate circle on a chart. Now, with better sonar and a little funding, they’d decided to look more closely.

They didn’t expect a pristine wreck. The initial explosion had scattered the ship like confetti. Subsequent salvage efforts had removed anything dangerous or obviously useful. But fragments remained—twisted steel, scattered across the seafloor.

“ROV ready,” a tech called from the control tent.

Lily and Cole ducked inside.

On a bank of monitors, the feed from the remotely operated vehicle flickered to life: a beam of light cutting through blue, then green, then the darker shades of depth.

Fish flitted through the beam, silver flashes in the gloom. The bottom rose slowly—sand, then patches of coral, then shapes.

At first, it was hard to tell what was natural and what wasn’t. The sea had grown fingers. Coral encrusted edges of metal. Barnacles softened lines.

Then the ROV’s camera swung past a plate of steel the size of a car door, bent inward. A row of rivets. The ghost of a hull curve.

“There,” Cole said quietly. “Part of the side.”

The pilot eased the ROV closer. Lily pressed a hand to her mouth.

Another shape loomed: a circular object half-buried, encrusted but unmistakable.

“Gun mount?” someone suggested over the comms.

“Or a winch,” another voice said.

They moved on. Pieces of deck grating. Sections of pipe. A twisted ladder.

And then, lying at an angle like a fallen signpost, a fragment of the ship’s nameplate.

SE P E N S, the letters read, gaps where S R had broken away.

Lily felt tears prick her eyes.

“That’s her,” she whispered.

Cole nodded, his jaw tight.

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s her.”

The ROV hovered there for a long moment. On deck, no one spoke.

It wasn’t a grand wreck, the kind that ends up in coffee-table books. No bow rearing up dramatically, no intact cabins. Just scattered bones of steel, half-claimed by the sea.

But it was enough.

Later, they would lower a small plaque, weighted and anchored near the nameplate fragment. It would read simply:

In memory of the officers and crew of USS Serpens (AK-97)

Lost here 29 January 1945.

They served in silence. We remember in kind.

As the plaque sank, bubbles rising around it, Lily closed her eyes.

She pictured her grandfather as a young man—laughing with Ellis in the berthing, grumbling about the coffee, writing in his little notebook.

She pictured Chief O’Hara barking orders, Lieutenant Harlow writing his carefully worded objections, Captain Peters staring out at the shore line and counting risks.

She pictured the flash in the night sky.

And she pictured, beyond that, decades of quiet. Of names in stone, of arguments in offices, of families wondering exactly how a ship could simply… vanish.

9. The Real Story

A year after the expedition, Lily sat in a folding chair at Arlington, watching her father listen to Commander Cole speak at the Serpens memorial.

“…we’re not here to re-litigate board findings,” Cole was saying. “We’re not here to point fingers at men who did their best in impossible circumstances. We’re here to say that the men of Serpens were not just numbers in a casualty table.”

He held up a copy of the little notebook.

“One of them, Seaman First Class Tommy Reyes, wrote in his journal that he and his shipmates were ‘working scared’—not frozen, not reckless, but fully aware that what they were doing was dangerous. He trusted his officers. He trusted his crewmates. He trusted that if something felt wrong, someone would speak up.”

Cole glanced at the stone behind him.

“History sometimes calls them ‘support ships,’” he said. “As if they were simply… background. But without ships like Serpens, the shells don’t get to the front. The missions don’t launch. The war doesn’t move.”

He took a breath.

“The real story after 1945 isn’t just that an ammunition ship exploded and vanished,” he said. “It’s that, for too long, the men on her vanished from our telling of the war. We remembered the battleships and the carriers. We forgot the freighters and the tenders. Today, with families like the Reyes’, we’re trying to fix that.”

He stepped back.

A bugler played taps. The notes rose thin and pure in the heavy air.

When it was over, people milled about in small clusters. Old veterans shook hands. Children tugged at programs.

Lily sat for a moment longer, letting it sink in.

Her father slid into the chair beside her.

“Your grandfather would’ve rolled his eyes at all this fuss,” he said softly.

“Probably,” Lily said. “Then he would’ve told the story of the potato crate again.”

They sat in companionable silence.

After a while, Lily spoke.

“You know what gets me?” she said. “The fact that the argument’s still going. About what to call it. Accident, enemy action, fate. People get so heated.”

Her father chuckled.

“That’s history,” he said. “Everyone wants the one sentence that explains everything.”

She shook her head.

“I don’t think there is one,” she said. “I think the one sentence is: ‘It was complicated, and people did their best, and sometimes that wasn’t enough.’”

Her father looked at her sideways.

“You should write that down,” he said.

She smiled.

“Maybe I will,” she said. “In a little notebook. Keep the family tradition going.”

They stood, one more family in a crowd of many, and walked away from the stone.

Behind them, the names stayed, etched in granite. Not forgotten, not fully explained, but finally part of a story big enough to hold both the flash in the sky and the arguments that followed.

Somewhere in the South Pacific, fish still weave through the rusted bones of the Serpens. Coral grows slowly over steel meant for war.

Ships pass overhead, bound for ports whose names were once battlefields.

Most of the sailors on those decks will never hear of AK-97. They’ll never know that, for a second in 1945, those waters were brighter than noon. That dozens of men disappeared so fast their own shadows couldn’t keep up.

But because a few people refused to let their memories sink, because a worn notebook made its way from a toolbox to a historian’s desk, because hard conversations were finally had in offices and at memorials, the forgotten ammunition ship that exploded and vanished is not quite so forgotten anymore.

She never got a glorious battle. She never fired a shot in anger.

But she did what she was built to do: she carried the weight of war, quietly, until the day the load was too much.

And for that, she earned her place in the story.

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load