When a Hardened N@zi Colonel Found Forbidden American Books Inside a Remote POW Camp, the Ideas He Discovered Sparked a Moral Battle That Became More Dangerous Than Any War He Had Fought

Colonel Wilhelm Hartmann had always believed he understood the world perfectly. Structure, order, and obedience—these were the pillars on which he had built his entire life. Even after capture, even after the war dissolved in chaos, he still thought the world outside his former regime was simply misguided, not morally different.

When he arrived at Camp Birchwood, an American-run POW facility hidden deep within the pine forests of Wisconsin, he carried that certainty like a shield. Other prisoners looked nervous, beaten down, or relieved to have survived. Hartmann, however, marched forward with the same rigid posture he had taught his soldiers. He believed captivity was temporary, that the world he knew would eventually rise again in some shape.

But none of that confidence prepared him for the quiet, unassuming discovery waiting for him on his first night—the thing that would quietly begin to unmake the life he had once chosen with absolute conviction.

CHAPTER I — The Books No One Was Supposed to Have

The barracks were warmer than expected, and the American guards treated the prisoners with a detached politeness that irritated Hartmann. It felt theatrical, unnatural. He assumed kindness had ulterior motives.

As he unpacked the few belongings allotted to him, he noticed a loose panel beneath the lower bunk. The flicker of curiosity—a feeling he rarely allowed—nudged him to peel it back.

Behind it lay a thin cloth-wrapped bundle. He pulled it out, expecting contraband tobacco or perhaps a hidden letter.

But instead… books.

Three of them.

All in English.

All worn, annotated, underlined.

All completely forbidden under the old regime.

Their titles meant little to him, though he recognized some ideas from whispered rumors:

A collection of essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson

A battered copy of “Democracy in America” by Alexis de Tocqueville

A thin anthology of American poetry

These were not weapons. These were not escape tools.

But they unsettled him more than either of those would have.

Who had hidden them? Why here? And why had the Americans allowed such materials inside?

He contemplated turning them over to the guards. But something—perhaps vanity, perhaps the desire to identify the subversive mind behind this little stash—made him hide them instead.

He told himself it was a calculated decision.

But it was curiosity.

The first crack in the armor.

CHAPTER II — Captain Alden’s Uncomfortable Hospitality

Camp Birchwood’s commander, Captain Thomas Alden, was a lanky man with a tired but gentle voice. He oversaw operations carefully, intervening only when necessary. It frustrated Hartmann to no end that Alden treated even senior officers like him with the same tone he used toward the teenage guards.

“Colonel Hartmann,” Alden said during their first official meeting, “you’ll find this camp quiet. We don’t run on force unless we need to. If you have concerns, you can bring them to me directly.”

Hartmann bristled at the lack of ceremony.

“You presume much, Captain,” he replied stiffly.

Alden shrugged. “War is over. Presumption is all any of us have left.”

That answer irritated Hartmann for reasons he couldn’t explain. He spent the first week cataloging the camp’s routines, convinced there must be hidden manipulations or strategies designed to weaken discipline. But the Americans seemed neither vindictive nor naïve. They were simply… humane.

It was disorienting.

More disorienting than hostility would have been.

CHAPTER III — The Poetry He Didn’t Mean to Read

For days, he left the books untouched. He told himself the English was too dense, that poetry was frivolous, that democratic philosophy was propaganda.

But late one night, when the barracks slept and he found himself restless, he unwrapped the bundle again.

The poetry anthology fell open to a page marked by a torn strip of cloth.

The poem was by someone named Langston Hughes.

Simple. Direct.

Yet it cut straight through the ideological armor he’d worn for decades.

It spoke of longing.

Of dignity.

Of a voice insisting on its right to exist.

He frowned, unsettled by the clarity of the emotion. Emotion had always been treated as weakness—a distraction, something to be controlled. But here it was presented without apology, without shame.

He closed the book, but the words stayed with him.

The second crack in the armor.

CHAPTER IV — The Young Guard Who Asked Too Many Questions

Private Eli Turner couldn’t have been more than nineteen. Energetic, curious, annoyingly earnest. He had been assigned to supervise the barracks during meal hours, and though Hartmann initially ignored him, the boy had a way of lingering with his questions.

“You speak English well,” Turner commented one day.

“Well enough,” Hartmann replied curtly.

“So… do you ever read American books?”

Hartmann stiffened. “Why do you ask?”

Turner shrugged. “A lot of prisoners read. Helps pass time.”

For a brief, irrational moment, Hartmann thought Turner knew about the hidden volumes. But the boy walked away without further comment.

Still, the question stayed with him.

And that night, he opened Emerson.

CHAPTER V — The Dangerous Idea Called “Self-Reliance”

He expected propaganda. He expected sentimental nonsense.

Instead, he found a bold argument that individuals—not the state, not tradition, not authority—should shape their own thoughts.

“Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.”

Hartmann read the line twice.

Then a third time.

It felt like an accusation.

A direct challenge to everything he had been trained to believe.

The essay wasn’t loud or fiery.

It was calm.

Unapologetic.

And impossibly dangerous.

Because it made him remember things he had spent years suppressing—doubts, questions, moments when he had disagreed silently with orders but followed them anyway.

He felt a knot tightening in his chest.

He slammed the book shut.

For the first time since arriving at Birchwood, he looked genuinely afraid.

CHAPTER VI — The Debate That Turned Into a Storm

A week later, Hartmann approached Captain Alden with a request he never imagined he would make.

“Do you have more books,” he asked, “written by American philosophers?”

Alden raised an eyebrow.

“That’s quite a shift.”

“It is an inquiry,” Hartmann said stiffly. “No more.”

But Alden had been watching him carefully.

“You’re trying to understand why we think the way we do,” the captain said softly.

Hartmann didn’t answer.

Still, Alden arranged for weekly discussion sessions between officers and willing prisoners. Some discussions were polite. Others became heated. And during one particularly charged meeting, a fellow prisoner accused Hartmann of abandoning his past, of betraying his former comrades.

The argument escalated into a near physical confrontation before guards intervened.

That night, Birchwood felt colder than usual.

Words echoed in Hartmann’s mind—accusations from other prisoners, but also questions from the books he had been reading.

Was he changing?

Or was he simply discovering a version of himself that had always been there, buried and ignored?

CHAPTER VII — Tocqueville and the Mirror No One Wants to Face

“Democracy in America” was the thickest book in the stash. It took Hartmann weeks to read, and some chapters required him to stop and walk outside just to clear his thoughts.

Tocqueville’s observations about equality, governance, and the power of individuals to shape their own communities challenged everything Hartmann had been taught.

He found himself arguing with the book out loud.

He found himself defending it in debates.

He found himself unwilling to hand it over even when the hidden owner—an older prisoner named Klaus Reinhardt—eventually confessed the books were his.

Reinhardt had been a teacher before the war.

He had hidden the books not because they were contraband in the camp, but because many prisoners were still hostile to ideas they had been taught to fear.

“You read them now,” Reinhardt said quietly. “Keep them, if you wish. Someone should.”

Hartmann didn’t know how to respond.

CHAPTER VIII — The Question That Broke His Certainty

During a late-winter discussion session, Captain Alden asked a simple question:

“Colonel, what do you believe freedom means?”

Hartmann opened his mouth automatically—ready to give a rehearsed political answer.

But none of the words felt true anymore.

He looked around the room:

at Reinhardt, quietly hopeful

at younger prisoners, confused or wary

at guards, simply listening

And for the first time in his life, he admitted he didn’t know.

Silence followed.

Alden didn’t smile or gloat.

He simply nodded, as if acknowledging a turning point Hartmann himself had not fully recognized.

CHAPTER IX — The Letter He Couldn’t Bring Himself to Finish

Spring arrived slowly, painting the edges of the forest with new life. Hartmann found himself writing frequently—letters he never sent. To family members. To former colleagues. To younger officers he had once mentored.

He tried to explain the ideas he was reading.

He tried to describe the internal struggle that kept him awake at night.

But every letter ended in the same way:

with the pen falling still,

and a tightness in his chest he could not yet resolve.

How could he explain transformation when he didn’t fully understand it himself?

CHAPTER X — The Choice in the Library

One morning, Captain Alden summoned him.

“We’re updating camp privileges,” he said. “I’d like you to oversee the small library we’re building. You have the strongest English skills—and frankly, you’ve been reading more than any prisoner I’ve met.”

It was not an order.

It was an invitation.

And surprisingly, he accepted.

Organizing those shelves became the most meaningful work he had done in years. He recommended books, translated summaries, encouraged discussions. He ensured that every volume—American, French, British—was available to anyone willing to read, regardless of rank or past loyalty.

Other officers noticed the shift in him.

Some were quietly supportive.

Some resentful.

Some frightened by the possibility that their beliefs were not as immovable as they once thought.

But the library grew.

And so did the conversations.

CHAPTER XI — The Day He Finally Understood

Months later, Hartmann stood outside the barracks with Private Turner, now twenty and more confident. The young guard asked a question Hartmann had once dismissed.

“Sir… do you ever think about what you’ll do after all this?”

Hartmann looked toward the forest, where sunlight filtered through tall pines.

For the first time, he allowed himself to imagine a future not dictated by obedience, ideology, or fear.

“I think,” he said slowly, “I will spend the rest of my life learning how to be a better man than the one I used to be.”

Turner didn’t respond at first.

Then he simply nodded, understanding more in that one sentence than Hartmann had expressed in months.

CHAPTER XII — Release and the Road Forward

When Hartmann was eventually released, he took only a few items with him:

A notebook full of unfinished letters

The poetry anthology

Emerson’s essays, now worn from use

A small American flag Turner had secretly slipped into his bag “as a reminder of the place you started over”

As he stepped beyond the camp gates, he realized he did not feel like the man who had arrived months before—rigid, certain, unmovable.

He felt uncertain. Open.

And strangely free.

He didn’t know where life would take him now.

But for the first time, he was ready to let his own conscience—not anyone else’s—guide him.

And that, he understood at last, was the idea that had been waiting for him all along.

THE END

News

A little girl who whispered to a CEO that her mother hadn’t come home during a dangerous snowstorm, sending him rushing into the night and uncovering a truth that would change all three of their lives forever

A little girl who whispered to a CEO that her mother hadn’t come home during a dangerous snowstorm, sending him…

A wealthy mother who took her twin children out for a celebratory dinner

A wealthy mother who took her twin children out for a celebratory dinner unexpectedly crossed paths with her ex-husband, leading…

A son who returned to the hospital earlier than expected to check on his recovering mother — only to discover that his wife’s well-intentioned choices were unintentionally putting her at risk, forcing the family to confront truths they had long avoided

A son who returned to the hospital earlier than expected to check on his recovering mother — only to discover…

A billionaire who mocked a waitress in Spanish, assuming she wouldn’t understand a word, only to be stunned when her flawless response exposed his arrogance and transformed the entire atmosphere of the restaurant — and his own character

A billionaire who mocked a waitress in Spanish, assuming she wouldn’t understand a word, only to be stunned when her…

A young man who sacrificed his dream job interview to help a stranger on the street, unaware she was the CEO’s daughter — and how that single choice transformed his future in ways he never expected

A young man who sacrificed his dream job interview to help a stranger on the street, unaware she was the…

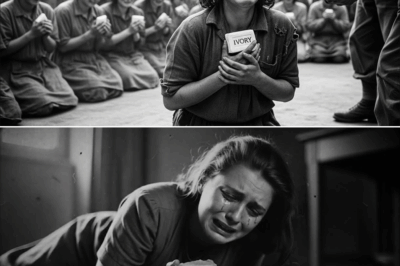

How a Simple Bar of Soap Opened Old Memories, Stirred Hidden Courage, and Helped Eighty-Seven Italian Women Partisans Finally Find Their Voices After Years of Silence in the Turbulent Summer of 1945

How a Simple Bar of Soap Opened Old Memories, Stirred Hidden Courage, and Helped Eighty-Seven Italian Women Partisans Finally Find…

End of content

No more pages to load