When a German General Visited an American POW Camp and Froze—Because the Prisoners Looked Healthier Than They Did at Home

The first thing the German general noticed wasn’t the fences.

It wasn’t the guard towers, either—not the silhouettes with rifles, not the searchlights, not the clipped, practiced rhythm of an American camp doing its work. Those were expected. Those were predictable. Those were, in a strange way, comforting—because they meant the world still made sense.

No, what stopped him cold was something he did not have a neat word for.

The prisoners.

They were standing in loose clusters near the mess hall, sleeves rolled, faces turned toward the late-afternoon sun like men stealing warmth. Some were laughing. Not the tight, nervous laugh you hear when people pretend they’re fine—this was easy, almost careless. One of them had a tin cup in his hand and was gesturing with it the way a man gestures in a beer garden when the conversation turns funny.

The general’s boots slowed on the gravel. His escort—a U.S. major with polite eyes—kept walking for two steps before realizing the visitor had stopped.

“General?” the major asked, careful.

The German general didn’t answer at first. He stared.

The men behind the wire looked… wrong.

Not wrong in the way defeat looked wrong—he had seen defeat. He had watched divisions melt into rumors, watched trucks run out of fuel, watched maps become lies. He had seen men in surrender lines with hollow cheeks and eyes that had already given up arguing with hunger.

But these men—these German prisoners in an American camp—had color in their faces.

Their uniforms, though faded and mismatched, hung on them without the desperate looseness he’d grown used to. Their hands were not shaking. Their shoulders weren’t folded inward like paper.

And the most shocking detail of all, the detail that made his stomach tighten as if someone had pulled a rope from inside him—

They looked… well.

Healthy. Clean. Almost handsome in the blunt, ordinary way soldiers could look when they’d slept and eaten and shaved.

The general’s mouth went dry.

Because he couldn’t stop thinking of the men still out there—still in the collapsing Reich—still starving on the roads, still stumbling past bomb craters and burned-out stations, still staring at empty store shelves and pretending the end wasn’t coming.

Compared to them, these prisoners looked like men who’d been delivered from the worst part of war, not men who’d lost it.

His escort cleared his throat gently, as if to nudge him back into the script.

“Welcome to Camp Mason, sir,” the major said. “We’re glad you could make the visit.”

The German general finally blinked, the spell breaking just enough for words.

“They are…” he began, then stopped.

The major waited.

The German general tried again, quieter. “They are—how do I say it—so presentable.”

The major’s expression didn’t change. He’d heard versions of this before.

“They’re fed,” he said simply. “They’re housed. They’re working. They’re not under fire.”

The German general looked again. Presentable wasn’t the right word.

They looked like life had returned to them.

And that was the part he couldn’t forgive.

His name, for the purpose of this story, doesn’t matter as much as the fact that he wore the rank. A man with authority, a man who had signed orders, a man who had watched younger men salute him and then walk into danger because of something he’d decided at a desk.

He had been captured months earlier, when everything began to unravel. He had been separated from his command and moved through a chain of temporary holding areas before the Americans decided, for reasons of intelligence and protocol, that he should be shown what American captivity looked like.

It was a visit, yes—but it was also a message.

This is what your men become when they stop fighting us.

In the car on the way to the camp, he had prepared himself for the obvious.

He expected bitterness.

He expected humiliation.

He expected his countrymen behind wire to have the dull, furious eyes of men who felt they’d been cheated.

What he did not expect was the sound he heard as the camp came into view:

A harmonica.

It drifted across the air in lazy notes—unhurried, almost cheerful. Not a marching song. Not a funeral. Something casual, something someone played because they were bored in the afternoon.

The general’s fingers curled inside his gloves.

“Music,” he muttered.

The American major glanced over. “Keeps them calm. Keeps them busy.”

The general thought: Calm.

He hadn’t heard calm in Germany in years.

At the camp gate, a military policeman checked papers with bored professionalism. The wire fences stood tall, but what struck the general wasn’t the height.

It was the order.

Everything was arranged. Everything made sense. The walkways were swept. The barracks sat in rows like obedient paragraphs. Men moved in lines when they had to, but they also moved freely within boundaries, like people who understood rules and had stopped fighting them.

The camp smelled like dust and soap and cooked food.

Cooked food.

His stomach betrayed him with a faint twist, and he hated it.

They passed the mess hall. A group of prisoners carried crates—vegetables, maybe—laughing at something one of them said. They looked up as the small entourage passed, curiosity flickering, then dissolving back into their day.

The general waited for the expected moment—someone shouting an insult, someone spitting, someone performing hatred for the sake of pride.

Instead, one prisoner nodded politely, almost automatically, as if the general were simply another officer passing on the road.

That nod hit the general harder than any insult could have.

Because it said: I’m surviving.

It said: Whatever you told us about the enemy, look where we are now.

It said: We are still here.

They toured the infirmary. White sheets. Clean instruments. Prisoners lying on cots under thin blankets, watched by medical staff who didn’t look afraid.

The general’s throat tightened when he saw a young German soldier with his hair neatly trimmed, reading a book with the slow focus of a man who no longer had to scan the horizon for explosions.

“What is he reading?” the general asked, surprised at his own curiosity.

The major glanced. “English primer. Some of them try to learn.”

The general’s lips pressed together.

Learning English in captivity. It sounded like betrayal and wisdom at the same time.

They moved on.

In the recreation area, men played soccer. Their boots kicked dust. Someone shouted a joke. Someone else made a dramatic dive and got up laughing, waving off the mock outrage.

The general felt something cold form behind his ribs.

His men looked younger here.

Not in age—war had carved lines into all faces—but in spirit, in posture, in the subtle way they weren’t bracing for the next blow.

They looked like men temporarily paused from destruction.

The general turned sharply toward the major.

“Do they receive—” he searched for the right word, the word that wouldn’t sound like begging. “Do they receive adequate rations?”

The major didn’t take offense. “They receive rations based on policy, and what we can supply. There are international rules. And we’ve got food.”

The general heard the unsaid part:

We have enough to feed our prisoners.

He thought of Germany—of trains that didn’t run, fields abandoned, cities turned into rubble and smoke, children with hollow cheeks, old women carrying buckets like they carried the whole war.

He thought of officers in his own army who had insisted, even as reality collapsed, that endurance would be rewarded.

Rewarded with what?

This?

His own men behind wire, looking better than the ones still “free”?

The general’s vision narrowed. The camp seemed brighter, almost obscene.

They paused near a small bulletin board posted with notices in German and English: work assignments, rules, library hours, a list of sports matches. The general stared at the neat handwriting, the careful translations.

“Library,” he read aloud, voice low.

The major nodded. “Keeps them occupied. Helps discipline.”

Discipline.

The general almost laughed, but the sound died in his throat.

He had spent years trying to impose discipline through fear and ideology and the promise of victory.

Here, discipline came from routine… and something worse:

Dignity.

Not full dignity. Not freedom.

But enough to keep a man from becoming an animal.

Enough to let a man look in a mirror and still recognize himself.

The general’s hands shook slightly. He tucked them behind his back so no one would see.

A prisoner walked past carrying a bucket, stopped, and stared openly at the general’s uniform. For a heartbeat, they locked eyes.

The prisoner’s gaze wasn’t hateful.

It was assessing.

Then, quietly, the prisoner said in German, “Herr General.”

Just that. No insult. No praise.

Then he walked on.

The general stood frozen, feeling as if he’d been slapped by politeness.

Later, they sat in a small office near the administration building. The major offered coffee. The general stared at the cup like it was a trick.

He sipped.

Real coffee.

Not the thin substitute he’d grown used to. Not the burned water passed off as comfort.

He set the cup down with care, as if it might explode if handled wrong.

The major watched him with a calm that felt almost unfair.

“You seem surprised,” the major said.

The general exhaled slowly. “In my country,” he said, choosing each word like a minefield, “we were told… captivity here would be harsh.”

The major’s mouth tightened—not with anger, but with something like tiredness.

“War is harsh,” he said. “We try not to add to it when we don’t have to.”

The general stared at him. “Why?”

The major shrugged. “Because it keeps order. Because it’s policy. Because someday, our boys come home too.”

That last line landed deep.

Because it reminded the general of something he’d tried hard to forget:

The enemy was made of men who also wanted to survive.

When the tour ended, the major offered the general a final walk along the fence line. The sun was lowering now, turning the wire into thin gold lines. The prisoners moved toward evening routines—some heading to barracks, some to wash up, some still lingering, stretching, talking.

The general walked slowly, eyes scanning faces.

There were older men with tired eyes.

There were boys barely old enough to shave.

There were hardened soldiers with scarred knuckles and stubborn jaws.

And in many of them, there was something the general had not expected to see inside a prison:

Relief.

Not relief at being captured—no soldier wants that.

Relief at being out of the machine that had begun eating its own.

Relief at being away from the collapsing nightmare of the final months.

The general stopped again, unable to help himself, staring at one particular group: a cluster of prisoners gathered around a makeshift table, playing cards. Their laughter rose and fell like a living thing.

One of them looked up and smiled—a quick, automatic smile, like a man who had forgotten, for half a second, that he was supposed to be miserable.

The German general’s chest tightened painfully.

The major followed his gaze. “Some of them,” he said, “are going to remember America like this.”

The general’s voice came out hoarse. “They will return.”

The major nodded. “Eventually.”

The general swallowed. “And they will tell others.”

The major didn’t deny it. He simply said, “That’s usually how stories work.”

Stories.

The general suddenly understood what this visit had truly been.

Not a tour.

A warning.

Because if prisoners went home saying, “We were fed,” “We worked,” “We lived,” then everything the regime had screamed about the enemy would rot from the inside out.

The general leaned closer to the fence, watching the men behind it.

They looked… human.

And that was the most dangerous thing of all.

On the ride back, the general stared out the window at American roads, American fields, American normalcy. Trucks moved without panic. Houses stood with roofs intact. People drove as if fuel wasn’t a miracle.

His mind kept returning to one moment: the prisoner who had addressed him politely.

“Herr General.”

No hate. No desperation.

Just acknowledgment.

The general’s thoughts spiraled into a place he had avoided for years:

What if the war had been built on lies so large they required constant fear to keep them standing?

What if the enemy wasn’t the monster they had described?

What if the true monster had been the machine that demanded everything and returned only ashes?

He clenched his jaw until it ached.

A general was supposed to deal in reality. He was supposed to see the world as it was, not as speeches painted it.

And yet he had lived inside a painted world for too long.

Now, in one afternoon, the paint was peeling.

That night, in his own quarters, he could not sleep.

He kept seeing faces behind wire—faces with color, with life. He kept hearing laughter where he expected bitterness. He kept smelling cooked food.

At some point, he sat up, lit a cigarette with shaking hands, and stared into the dark.

A thought arrived, sharp and unwelcome:

If captivity here is this… then what are we fighting for anymore?

He imagined his men still in the field—still being pushed, still being told to hold lines that didn’t matter, still dying for ground that would be abandoned by morning.

He imagined the ones at home—families in ruins, children hungry, mothers exhausted, old men staring at empty horizons.

Then he imagined the prisoners again, playing cards, learning English, lining up for meals, living.

His cigarette burned down to his fingers before he noticed.

He crushed it out, breathing hard, as if he’d run.

He was a general. He was trained to make decisions.

But for the first time in a long time, he realized the war had made him good at one thing above all:

Explaining away the unbearable.

Tonight, the unbearable had stepped into sunlight and smiled behind a fence.

And he could not explain it away.

In the morning, he asked the American officer for one thing before the next transfer, the next interrogation, the next routine of captivity closed in again.

“A pencil,” he said.

The major raised an eyebrow. “To write?”

The German general nodded once.

He didn’t say what he would write. A confession? A report? A letter that would never be delivered?

But as he took the pencil, his hand steadied, and his eyes hardened—not with hatred, but with clarity.

Because the shock of the camp had done something war itself had failed to do:

It had forced him to see his own side without slogans.

And in that clarity, the most dramatic battlefield truth of all emerged—not from gunfire, but from a fence, a mess hall, and a group of prisoners who looked startlingly alive:

Sometimes, the moment an army truly loses is not when it surrenders a city.

It’s when its own leaders realize the enemy can afford to treat captives better than the regime can treat its free citizens.

And once you see that, you can never unsee it.

THE END

News

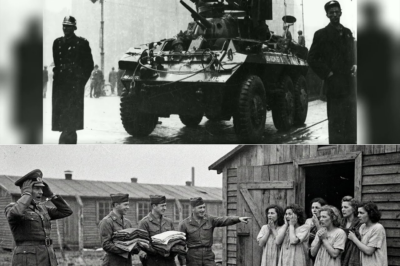

Shock in a Quiet Barracks: A Wehrmacht General Demanded Answers, and What He Saw in the American Women’s POW Ward Rewrote His Beliefs Overnight

Shock in a Quiet Barracks: A Wehrmacht General Demanded Answers, and What He Saw in the American Women’s POW Ward…

The Moment a Captured German General Misread the Scene—and Then Realized the Americans Were Doing Something His Own Army Never Learned: Mercy With Rules

The Moment a Captured German General Misread the Scene—and Then Realized the Americans Were Doing Something His Own Army Never…

A Captive General Asked for ‘His Women’—But the Americans Led Him Through a Quiet Barracks Where Compassion, Not Revenge, Delivered the Sharpest Defeat

A Captive General Asked for ‘His Women’—But the Americans Led Him Through a Quiet Barracks Where Compassion, Not Revenge, Delivered…

The Night Roosevelt Read One Quiet Sentence About Normandy—and Answered With Words That Made Everyone in the Room Understand Europe’s Future Was Now

The Night Roosevelt Read One Quiet Sentence About Normandy—and Answered With Words That Made Everyone in the Room Understand Europe’s…

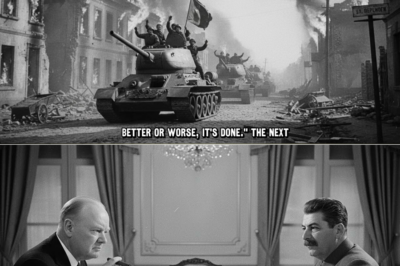

When the West Stopped at the Elbe: The Meeting Where Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton Realized the Red Army Would Reach Berlin First

When the West Stopped at the Elbe: The Meeting Where Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton Realized the Red Army Would Reach…

In the Cellars of Berlin, They Whispered “It’s Not Rumor Anymore” as Strange Voices Rose Up the Stairwell and the City Finally Felt Its End

In the Cellars of Berlin, They Whispered “It’s Not Rumor Anymore” as Strange Voices Rose Up the Stairwell and the…

End of content

No more pages to load