When a drought-worn farmer pulls an injured pilot from a silent crash and hides her in his weathered barn, she vanishes at dawn—then thunders back in a silver jet, with a promise that rewrites debts, destinies, and every whispered rumor in town

The sky over Dry River had a way of pretending it was endless, even when the land below it stubbornly refused to yield anything at all. Fields lay flat and dull as if painted in chalk. The creek had tunneled inward and gone quiet months ago, then given up altogether. By late afternoon the air became a shimmering wall; by evening it felt like a held breath. The town had learned to speak softly under that sky.

Elias Boone had learned to listen.

He listened to the faint groan of the windmill as its blades turned lazily in wind too thin to mean anything. He listened to fences creak like old knees, to the distant rumble of trucks on the highway that carried other people’s luck past his mailbox. He listened to numbers—always numbers—the strapped ledger he kept beneath a coffee can on the kitchen shelf: seed bills, feed bills, fuel, taxes. Listening had become a kind of occupation, a substitute for hope. When you had nothing to sow, you learned to hear small things.

On an evening browned by dust, Elias sat on the porch steps with a cracked mug of water and watched the light slide lower, turning his fallow fields into sheets of tarnished metal. A hawk hung above the fence line, then folded and disappeared somewhere beyond the grove. The quiet had a weight to it, like a blanket that meant well but pressed down too hard.

He heard the trouble before he saw it, a sound that did not belong to Dry River. A quick, startled buzz that grew into a desperate coughing from the west. Elias stood. The sound cracked open into a ragged roar, wavered, and fell. It was close—closer than close—and wrong in a way that made his bones jump: an engine about to quit on a sky that would not forgive it.

He ran.

Past the barn, past the tank, down the path that had been a driveway before the ruts outnumbered the rocks. Dust rose behind him, the air taste of pennies. Beyond the south field a low hill lifted the land like a knuckle. The sound came over it, a small plane dipping, struggling, its nose twitching as if sniffing for a place to fall. For a breath the sun caught on the fuselage, and the plane flashed like a coin flipping heads to tails—it cleared the fence, clipped a stubborn mesquite, then slammed into the dead wheat with a crumpled sigh that traveled the ground to Elias’s boots.

Everything went strange-quiet again.

Elias didn’t stop to consider wisdom. He vaulted the fence, stumbled once, and reached the wreck at a run. The plane had skidded into a shallow ditch and tilted there like a toy discarded mid-argument. Steam drifted from the cowling; the propeller was bent in a way that made it look sorry for itself. The cockpit canopy was a spiderweb of cracks, sunburst lines radiating from a fist-shaped wound.

“Hey!” Elias shouted, voice croaking. “Hey, can you hear me?”

A face moved behind the crazed glass—pale, sharp, eyes bright with that particular brightness that happens when fear meets focus. A hand groped for a latch, failed once, then found it. The canopy gave an offended shudder and slid. Heat rolled out with the faint metallic smell of an overheated machine.

“I’m stuck,” the pilot said, breath hitching. She was young enough to make Elias feel older than he was, though her expression had the fixed calm of someone trained too hard to waste panic. A harness strap had locked across her shoulder, and her left leg was trapped beneath a panel kicked loose by the landing. Blood—only a little, not the kind to draw flies—streaked one eyebrow. “Fuel’s leaking.”

Elias leaned in. The spilled fuel—sharp, cold on a hot day—threaded the air. He smelled dust, hot rubber, and something like singed almonds. He found the buckle, thumbed it, and the strap freed with a clack that sounded louder than the crash. He lifted the panel jamming her leg and held it there, teeth set, while she tried to slide free.

“Count of three,” Elias said, even though counting had no purpose here other than being human. They moved together, and she gasped as her foot came clear. When he eased the panel back down it thumped like a drum. He offered his arm, and she took it, grip so steady it surprised him. They stumbled out and away from the plane, moving without grace but quick enough that the heat on their backs felt like a warning hand.

They made it to the fence line before the engine ticked heavily and went quiet for good. No flame followed—no dramatic fireball blooming into evening. Just the sound of metal settling into its own mistake.

She sank to the dirt, breathing hard, and pressed fingertips to her temple. “Thank you,” she said, and it wasn’t the kind of thanks said by habit. It was measured and real.

Elias peeled his hat off, fanned the air once, and put it back on. “Name’s Elias Boone. Don’t suppose this is a sightseeing tour?”

The corner of her mouth tipped. “Ana,” she said. “And no. Training run. Bird strike. The gauges went weird. I tried for the county strip, but…” She tilted her head toward the plane. “That happened.”

“You hurt bad, Ana?”

“Just scraped. Leg will complain tomorrow.” She squinted toward the plane, thoughtful in a way that made Elias wonder about the use of the word “training” and the brightness of her eyes. “Is there somewhere I can sit? Out of sight?”

He glanced at the road, the open land, the town spread thin and nosy as shadows. “Barn,” he said, and offered his shoulder again.

They moved slower this time. The sun slid down with them, drawing the heat out of the land like a thread. By the time they reached the barn, the sky had turned the color of a fresh bruise near the horizon and porcelain above. Elias shouldered the big door open. Inside: hay dust motes drifting in their own universe, soft smells of oil and wood, the long patient shapes of tools leaning against walls. He had built shelves from pallet wood three summers past and felt absurdly grateful to them now.

Ana eased onto an upturned bucket. “You have water?”

Elias fetched a jug from the sink and found a clean-enough tin cup. She drank as if there were a rule about it, then poured a splash into her palm and scrubbed gently at the cut on her brow. She tucked her hair back and looked at him over the rim of the cup with an expression that belonged more to meetings than barn aisles: assessing, appreciative, a little guarded.

“You didn’t call anyone,” she said.

“Phone’s in the house.” Elias shrugged. “And I figured you might want a minute before my neighbors come tradin’ stories for favors.”

Ana set the cup down. “I appreciate that.”

“You hungry?”

She laughed softly, surprised. “Am I allowed to say yes?”

Elias found bread, a jar of beans left from lunch, a heel of cheese that had survived July through stubbornness alone. They ate on the tailgate of his truck with the barn door cracked wider to invite the evening in. Crickets started their high, relentless fiddling. A single light blinked to life at the house and sent a yellow triangle onto the yard.

“So,” Elias said finally, “you fly for who?”

Ana glanced toward the opening in the door, measuring the space where a passerby might become a listener. “A program,” she said. “I can’t really—” She faltered, then met his gaze. “Nothing harmful. Just quiet. Training, logistics, communications—learning how to be small when the sky is big.”

“Being small is a specialty of mine,” Elias said dryly, and immediately regretted the complaint dressed up as humor. Ana’s expression shifted—sympathy without pity, precise as a tool placed back exactly where it belongs.

“You own the land?”

“Mortgage owns it. I rent part back to myself as a treat.” He tried to smile. “Been here all my life. My dad before me. Rain and I aren’t on speaking terms lately.”

She studied his face in the pause after that. “I’m going to ask for a favor you won’t like,” she said. “And I’ll make it right, if you let me. I need to vanish for a night. There will be questions I cannot answer today. If you keep the plane out of the gossip loop until morning, I can fix this. For both of us.”

Elias looked at the vague shape of the wreck through the barn gap. “Fix how?”

“I can’t say. Not because I don’t trust you—because I signed too many papers that say I don’t get to. But I have agency. And I won’t forget.”

He wanted to laugh at the drama of it, at the way the evening seemed to arrange itself into a story. He wanted to say, This is Dry River, Ana—stories don’t arrive in silver and leave IOUs. But he looked at her hands instead. They were steady. Not soft, not fancy, not the hands of someone rehearsing lines that sound good in a barn. And something in his chest that had been folded flat for years lifted its head.

“Hide a plane,” he said. “Sure. No problem.”

Ana’s smile flashed, quick as a bird. “Not the whole plane. Just…not the sight of it. I’ll pull the emergency beacon off now; you can shove the fuselage deeper into the ditch with your truck. Throw some tarps over it. In the morning, the right people will come, and nobody else will even remember what they did or didn’t hear.”

“That’s a mighty confident promise.”

“It’s a practiced one,” she said gently.

They worked in the hush of a decision made. Elias backed the truck down the field, nudged the wreck into a lower angle, and together they heaved old tarps over the cockpit, then dragged a sheet of corrugated scrap to lean against the nose like an improvised sunshade. The dusk had become night when they finished. The stars arrived chipped and sharp.

Back in the barn, Ana rolled her shoulders and winced. “Pain’s catching up.”

“You can bed down in the loft,” Elias said. “Hay’s clean. There’s a fan that whines like a philosophy teacher, but it moves air.”

She smiled at that, climbed the short ladder with careful insistence, and disappeared into the glow of the bare bulb. Elias set a radio on the workbench. He told himself he would sit for ten minutes and then go inside. He lasted five. The fatigue of not worrying for one brief hour rushed out of him and left something lighter.

He woke to the strange quiet of a barn where someone else is sleeping. He climbed the ladder to check on her and found the corner of the hay undisturbed. On the loft rail a note was clipped under a clothespin. He squinted, then found his glasses and read:

Elias—Thank you. I’ll be back before the heat learns your name today. Please don’t be afraid of morning noise. —A.

He stepped outside. The eastern sky was just beginning to pale. He had time, then, to doubt. Plenty of time to go inside, call the county, and let officials and questions and complicated forms pour into the day like marbles spilling off a table. He pictured the look on Sheriff Myles’s face when he explained: “A pilot asked me to keep quiet. She promised a better tomorrow.” The sheriff had a dependable frown that could make optimism look like malpractice.

Elias went to the kitchen instead and made coffee measured as if it were medicine. He wrote numbers in the margins of yesterday’s numbers, as if new arithmetic might reorder facts. He fed the dog. He watched the road. When he heard the morning arrive, it came not as the scattershot chorus of birds or the confident sound of delivery trucks, but as the low rolling thunder of engines.

Not from the road—from above.

Elias walked out to the yard, coffee mug forgotten on the railing. Over the ridge, a plane appeared, then another: sleek, purposeful, the kind of aircraft you see in magazines that talk about distance as if it were a trick of perspective. They were not low enough to be rude, but low enough to make the ground feel noticed. One circled once and angled toward the field beyond his ditch. The other drifted farther east and held.

The first jet—because it was a jet, bright as a comma—settled with a grace that made Elias’s heart knock once firm against his ribs. It set down where no runway existed because sometimes the world rearranges its rules in front of you. Dust plumed, swirled, and fell. The aircraft rolled to a neat stop near the edge of the stubbled field, a discreet distance from everything, like a guest unsure of which door qualifies as the front.

A hatch opened. A set of folding steps unfolded with an exactness that made Elias think of patient hands snapping a pocketknife shut. Ana came down, hair pulled back, wearing the same clothes as yesterday but carrying a different gravity.

“Morning,” she called softly, as if greeting a neighbor across a fence.

Elias, because the world had not entirely rewritten him overnight, said, “You brought friends.”

“Just one,” Ana said, smiling. “The other is a watchful neighbor.”

He laughed then, because it clicked into place all at once—not the details, not the machinery behind it, but the feeling of the mechanism. She wasn’t simply a student of flying. She belonged to a flight path with doors that could open over fields like his, with calendars that made room for sunrise and gratitude. Whatever the program was, it had a budget, and it had kept its promise.

“Come on,” she said, eyes warm now in a way that made him feel a little dizzy. “Let’s set your day right.”

They walked to the jet. A man in a faded ball cap stood a polite distance away, hands clasped in front of him. He nodded, said good morning, and then fell back into silence that was not empty but useful. Ana led Elias up the steps. The cabin inside was small and clean, with lines like a well-made tool. The air smelled faintly of citrus and something new. At a small table, two people sat with briefcases and courteous attention. They looked like the cousins of bankers who also knew how to change a tire. One of them—sharp-eyed, soft voice—said, “Mr. Boone,” as if they had known his name since before sunrise.

“Elias,” he corrected, suddenly aware of the dust on his shirt, the crack in his thumbnail, the weird sense of dream about all of it.

“Elias,” the soft-voiced one said. “I’m Mara. This is Cole. We represent a set of friends of Ana’s—call us a foundation with a fondness for the practical. We don’t do posters or speeches. We show up where people make choices for other people’s sake.”

Elias looked at Ana, who looked at him the way a bridge might look at a river it was glad to cross.

Mara slid a thin folder across the table. In it were documents explained in plain language and then explained again even plainer. They were not replacing the past or paving it over. They were untangling the present. The mortgage could be settled—today, all of it, penalties included—in exchange for a lien that would not attach to his soul but to a reasonable percentage of future harvests over a decade, with a forgiveness clause woven in at year five if conditions still ran against him. There was a credit line at a rate that did not require laughter to keep from crying. There were contacts for buyers who dealt in long contracts that did not punish bad years like personal failures. And there was one more page anchored to the back: a zero-interest loan to repair the windmill, replace the pump, reline the tank. The numbers were precise without being cruel.

“We don’t buy land,” Cole said. “We don’t flip it or collect your favorite tree with the deed. We make it possible for time to do its work.”

Elias felt dizzy again. He had braced for a catch and found a staircase. “And for this I…?”

“You saved Ana,” Mara said simply. “You listened when she asked for quiet. You left space for the right kind of noise.”

Ana touched the folder with one finger. “And because I gave my word.”

Elias swallowed. He thought of Sheriff Myles and his dependable frown, of neighbors who would claim they’d have done the same and then spend the rest of the summer proving otherwise. He thought of his father’s hands, cracked as the pond mud in late August, the way the man had told the sky goodnight as if it were a friend walking home the long way. He thought of the hawk and the little plane and the way the land sometimes pretended it was endless.

“I don’t know what to say,” he managed.

“‘Yes’ is useful,” Cole said, and his smile took any sting out of it.

Elias said yes.

They moved fast in a gentle way that felt like the opposite of a rush: signatures, verifications, a few calls placed by people who could make phones behave like instruments instead of alarms. When they finished, Mara closed her briefcase with a soft click. Cole stood and stretched the way people stretch after a long car ride. The man in the ball cap, who had said nothing and needed to say nothing, climbed the steps and murmured to Ana. She nodded.

“We’ll take the wreck out,” she said to Elias. “Someone will come with a flatbed that looks like it belongs to a roofing company. If anyone asks, tell them you’re fixing fence and curse the price of wire. No one will remember the sound if you give them the story they expected.”

Elias, startled into laughter, said, “You have a degree in small towns?”

“Several unofficial ones,” Ana said. “Also, your town deserves better stories. Maybe we can help with that too.”

He looked at the folder again. Something in his chest that had been lifting since dawn finally stood up. “You already did.”

They walked down into the morning. The second jet had drifted away sometime during signatures, and now the first hummed quietly, impatient in the polite way of living machinery. And because Dry River refused to let any day be too clean, a truck nose appeared over the rise—Sheriff Myles, hat already committed to the expression his face was preparing.

He pulled up slow, engine ticking, elbow hooked out the window. He took in the sight of a sleek aircraft on a field that had never asked for one, a farmer standing beside it like the end of a riddle, a woman with a cut on her brow smiling like the answer.

“Mornin’, Elias,” the sheriff said, slow as syrup you can’t afford. “I heard a rumor, and the rumor had the kind of legs I don’t trust.”

“Morning, Sheriff,” Elias said. He gestured at the field with a generous sweep he had not practiced. “Fence repair. Price of wire is daylight robbery.”

Myles blinked once. Twice. His eyes slid to Ana, whose expression managed to be both courteous and empty, like a guest at a party where the host forgot their name. His gaze returned to the jet and stalled there, then thought better of it and came back to Elias.

“You all right?” he asked, the real question underneath the decorations of authority.

“Better than,” Elias said, and the truth of it warmed his tongue.

The sheriff studied him another breath. Then he nodded, faintly. “If you need anything…,” he said, a sentence behind which a dozen other sentences lived.

“Got it covered,” Elias said, and discovered that the words didn’t sound like bluff coming from him. They sounded like plan.

Myles tipped his hat and rolled away, the rumor’s legs shortening with each yard.

Ana exhaled. “He’s good at his job.”

“He is,” Elias said. “And now he gets to be good at not doing part of it.”

They stood together for a long minute that grew comfortable. The man with the ball cap signaled. It was time. Ana offered her hand, then, as if talking to herself, said, “You could have run the other way.”

“You could have flown past.”

She shook his hand once, firm. “I’ll be back,” she said, and it wasn’t an echo of the note from the loft. It was a promise of a different shape.

The jet lifted with a grace that framed the morning like punctuation. It cut a neat line into the sky and was gone, leaving behind the faintest tremble in the tawny grass, the smell of clean heat, and a man standing in his own field holding a folder that felt heavier only because it had weight worth carrying.

The flatbed arrived an hour later with the humble self-importance of a vehicle that does ordinary things very well. Two men in shirts the color of faded sky eased the wreck onto the bed, strapped it down, and nodded to Elias as if they’d just picked up a water heater that decided to nap in the wrong yard. By noon there was nothing to see but a set of tire marks that matched a dozen other sets, the sort of marks no one notices unless they have chosen to add you to a story.

Elias spent the afternoon doing something reckless: he planned. He walked the fenceline with a tape measure and optimism in his pocket. He called the parts store and said sentences like “this week” and “let’s go ahead.” He stood by the windmill and listened not to its groan but to the way it might sound tomorrow. He drank water cold from the jug and did not taste pennies. He took the ledger from under the coffee can and laid it on the table without dread. He drew lines not to contain but to point. He wrote numbers like verbs.

Toward evening, when the heat had softened enough to allow cheek and breeze to speak kindly to each other, a shadow passed over the yard. Not a jet. A small, sky-colored helicopter that might have been a dragonfly if dragons had gone to finishing school. It drifted to a hover near the barn and then settled with a sigh. Ana stepped down, hair unhurried by wind now, a canvas bag over one shoulder.

“You said you’d be back,” Elias called, too happy to pretend surprise.

“I’m tidy,” she said. “And I forgot to tell you about the buyers.”

She did, sitting on the tailgate again like they had known each other longer than a day, listing off names and dates and what each name liked to accomplish when. She left behind a map scribbled with phone numbers, a thermos of coffee that smelled improbably like oranges, and a small package he didn’t open until after she left: a watch, simple, with a band the color of wet earth. Engraved on the back, a sentence that felt like a rope thrown across a wide space: For choosing to arrive.

Weeks turned. Clouds learned to behave. The creek tried on its old voice and kept it for days at a time. The windmill whirred with something like gratitude. The first harvest didn’t sing; it hummed. Humming was more than enough. When people asked, Elias shrugged and talked about stubbornness and good timing, about finally switching seed and how a friend of a friend had done him a kindness on a contract. You do not perform a miracle and then expect applause for noticing it.

But on certain evenings, when the sky over Dry River pretended it was endless and the land below it decided not to argue, a smooth shadow would pull itself across his field. A plane would etch a polite arc above his fence line and tilt a wing in a gesture that was either physics or affection. The dog would bark once, for form. And Elias Boone, struggling farmer, ledger carrier, listener of small sounds, would tip his hat toward the biggest sound he had ever kept quiet, and feel something in him answer:

Yes.

News

Her Mother-in-Law Called Her “Lazy” and Refused to Let Her Eat Because She Was Pregnant—But When the Family Doctor Arrived Unexpectedly and Asked One Question, the Truth She’d Been Hiding for Months Finally Shattered the Whole House.

Her Mother-in-Law Called Her “Lazy” and Refused to Let Her Eat Because She Was Pregnant—But When the Family Doctor Arrived…

When My Mom Banned Me From the Family Dinner at a Fancy Restaurant, I Burst Out Laughing and Asked the Owner for a Seat — What Happened Next Made Everyone at the Table Realize Who They Had Truly Been Eating With.

When My Mom Banned Me From the Family Dinner at a Fancy Restaurant, I Burst Out Laughing and Asked the…

“The Lesson They Never Expected to Learn”

After a Group of Students Attacked a Young Teacher, Leaving Her in a Coma, a Single Father and War Veteran…

The Billionaire CEO Pretended to Be Asleep to Test His New Maid’s Honesty — But When He Opened His Eyes and Saw What She Was Doing by His Bedside, He Realized He’d Been Testing the Wrong Person All Along.

The Billionaire CEO Pretended to Be Asleep to Test His New Maid’s Honesty — But When He Opened His Eyes…

My Brother Stole My Film Premiere, My Script, and My Spotlight — He Walked the Red Carpet Wearing My Dream. But Three Days Later, at the Airport, Justice Arrived in an Envelope That Made Him Drop Everything He’d Faked.

My Brother Stole My Film Premiere, My Script, and My Spotlight — He Walked the Red Carpet Wearing My Dream….

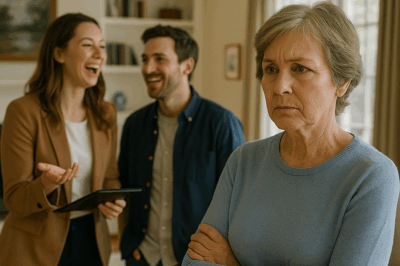

I Heard Laughter Coming From My Living Room, But When I Looked Inside, My Daughter-in-Law Was Showing My House to a Buyer—Smiling as If She Already Owned It. What Happened Next Changed Everything I Believed About Family.

I Heard Laughter Coming From My Living Room, But When I Looked Inside, My Daughter-in-Law Was Showing My House to…

End of content

No more pages to load