When a Broke Father Whispered, “Do You Have an Expired Cake for My Daughter?” in a Grocery Store Bakery, the Millionaire in Line Behind Him Heard Everything—and What Happened Next Tested Pride, Policy, and the True Meaning of Help

The bakery counter at Greenway Market always smelled like celebration.

Sugar and butter and vanilla floated over the hum of the store—the beeping scanners, the rolling carts, the chatter. It was a Tuesday evening, the kind of gray, forgettable day that usually slid off the calendar without leaving a mark.

But for three people in that bakery line, it would feel like a page someone tore out and kept.

Noah Mercer stood third from the front, one hand in his coat pocket, the other holding a tiny paper number: 42. Flour dust hung in the air like faint smoke. Behind the glass, rows of cupcakes, frosted cakes, and tarts sat under soft lights, each one a small, edible promise.

He checked his phone.

Two new emails.

One calendar reminder.

One text from his assistant: Board packet for Thursday attached. Need your note on the food waste slide.

He flicked it away.

Not now.

His driver had dropped him off on the corner under protest—“Sir, I can have someone bring it”—but Noah insisted. He wanted to pick up his niece’s cake himself. He could afford to buy the whole bakery, but he still liked the simple ritual of waiting, pointing, paying. It made him feel, for a minute, like any other guy in line.

The man in front of him did not look like any other guy in line.

He looked like someone who hadn’t had a break in a very long time.

Wrinkled navy work pants. A jacket that had seen better winters. Hands rough, knuckles chapped. His hair needed a cut; his beard was three days past tidy. He held his own paper number—41—like it might evaporate if he wasn’t careful.

In his other hand, he clutched a small plastic bag with store-brand spaghetti and a can of tomato sauce. Nothing else.

No vegetables, no meat.

Just… enough.

He kept glancing over his shoulder, toward the front of the store, as if he’d left something there.

Or someone.

“Forty-one!” the bakery clerk called.

The man stepped forward.

The clerk was young, maybe twenty, with a brown ponytail tucked under a Greenway cap. Her name tag read SARA. She offered him a customer-service smile, the kind that said she’d been trained to be cheerful on a timer.

“What can I get you?” she said.

He cleared his throat.

Up close, Noah could see the tension in the man’s shoulders, the way his fingers flexed on the plastic bag.

“Um,” the man said. “I… I was wondering if you had any… any expired cakes.”

The word expired landed oddly in the air.

Sara blinked.

“Sorry?” she said.

“Expired,” he repeated, quieter this time. “Almost expired. Or, you know, yesterday’s. The ones you don’t sell.”

He tried to smile, like he knew how ridiculous he sounded and hoped that acknowledging it would make it less so.

“For my daughter,” he added quickly. “Her birthday’s tomorrow. She turns eight.”

Noah felt something twist, deep and immediate.

Sara’s customer-service smile faltered.

“Oh,” she said. “Um. We… we don’t sell expired items, sir. I can show you our discounted rack near the bread aisle. Day-old stuff.”

He shook his head.

“I looked,” he said. “They’re all still… too much.”

His cheeks colored, as if the price tags had slapped him.

“I’ll be honest,” he said, words coming faster now, as if they’d pent up all day. “I’ve got eleven dollars after rent and… and everything. I can maybe do six on a cake and still get her candles and, you know, some juice. I thought maybe you had something you were going to throw away anyway. I don’t care what it looks like. Just… just something with frosting that says it’s her birthday.”

Noah stared at the back of his jacket.

The store around them kept moving—carts rattling, kids whining for cereal, the PA system calling for a price check—but the bakery counter felt suddenly very still.

Sara’s eyes darted to the side, toward the door that led to the back prep area.

“I’d have to ask my manager,” she said. “We’re not supposed to—”

“Please,” the man said.

It wasn’t the word itself, but the way he said it—like he was trying not to use it, but had run out of options.

“My name’s Miguel,” he added, as if that made him more real, more deserving. “I’m not trying to… I’m not looking for free stuff every day. I just… she told her class she was having a cake. I didn’t know she said that until her teacher mentioned it this afternoon.”

He swallowed.

“I can’t show up tomorrow with nothing,” he said. “She’s eight.”

Sara’s throat moved.

“Let me… let me see what we have,” she said.

She disappeared through the swinging door.

Noah should have looked away.

He should have checked his phone, pretended he was distracted, given the man the privacy of his embarrassment.

Instead, he watched.

Miguel shifted his weight, plastic bag crinkling in his grip. He stared at the cakes behind the glass—thirty-dollar masterpieces with sculpted roses, twenty-dollar sheet cakes with cartoon characters and airbrushed balloons.

His gaze snagged on a small, round, white cake.

Strawberry filling.

Pink frosting.

Eight candles would fit perfectly.

He blew out a slow breath and looked away.

Noah’s jaw clenched.

He remembered a kitchen so small you could touch the fridge and the stove at the same time. A mother counting coins at a table with a wobbly leg. A birthday where the “cake” had been a stack of pancakes with a candle jammed in the top.

He had sworn, at sixteen, that his kids—if he ever had them—would never have to pretend pancakes were cake.

Fate had chuckled and given him a company instead of kids, but the vow had stuck.

The bakery door swung open again.

Sara stepped out, followed by a man in a crisp shirt and a darker green tie. His name tag read TOM — BAKERY MANAGER.

He had that tense, hurried air of someone who believed he was always fifteen minutes behind schedule.

“Miguel, is it?” Tom said.

Miguel squared his shoulders.

“Yes,” he said.

“I understand you’re asking for expired product,” Tom said. “We can’t sell expired product. Liability. Health department. It’s against policy.”

Miguel nodded quickly.

“I know,” he said. “I’m not asking you to sell it. I mean, I can pay a little, but even… even if you were going to throw it out. I used to work in a restaurant. I know how that goes. I thought maybe—”

“Company policy is we dispose of anything past the sell-by date,” Tom said, like he was reading from a manual. “We log it, we toss it. We don’t donate it, we don’t discount it, we don’t give it away.”

He spread his hands in a gesture that said What can you do?

Miguel swallowed.

“It’s just for my daughter,” he said. “If it’s almost expired but still okay to eat tonight, I don’t… I don’t care if it’s perfect. She won’t care. I just want her to have something with frosting and a candle. I can give you what I have. Six dollars. Seven if I pull the coins from my truck.”

Tom’s jaw worked.

“If I did it for you,” he said, voice tightening, “I’d have to do it for everybody. Word gets around. Then every person who forgot to plan wants a free cake at the last minute. This is a business, not a charity.”

The words hit like a slap.

Miguel flinched.

“I didn’t forget to plan,” he said, a thread of frustration in his voice now. “I planned. The plan was to pick up an extra shift this week. It got cut.”

He lifted a hand, then dropped it.

“You know what, forget it,” he muttered. “I shouldn’t have asked.”

Sara’s eyes flicked between them, anxious.

Noah felt something inside him snap.

This wasn’t his business.

He knew that.

He also knew he was going to open his mouth anyway.

“Excuse me,” he said.

They turned.

Tom’s expression shifted from tight patience to polite surprise when he registered who was speaking—a tall man in a clean coat, good shoes, watch worth more than some people’s cars.

“Sir?” Tom said.

Noah stepped forward.

“I’ll pay for his daughter’s cake,” he said. “Whatever the price. Fresh. Full price. And I’m not asking for the discount rack. I want the nicest one you’ve got that can say ‘Happy Birthday’ on it.”

Miguel stiffened.

“No,” he said quickly. “Thank you, but no.”

Noah blinked.

“It’s really not a big deal,” he said. “I can afford it.”

“That’s the problem,” Miguel shot back.

His voice wasn’t loud, but it had an edge now.

“You can afford everything,” Miguel said. “I can’t. I asked them because I thought maybe they’d help me out without making me feel like… like this.”

He gestured vaguely to the space between them.

A few people in line behind Noah were watching now, pretending not to.

“I’m not looking for a rich guy to swoop in and rescue my kid’s birthday,” Miguel said. “I just… I thought maybe the store could see me as more than a problem.”

The words stung more than Noah expected.

“I didn’t mean to make you feel like a… project,” he said. “I just heard what you said and—”

“And you felt bad,” Miguel said. “So you pulled out your card. That’s easy for you. You leave here feeling like a good person. I leave here feeling like I needed a stranger to buy my kid’s cake.”

He shook his head.

“I appreciate the thought,” he added, and Noah could tell he meant it, which somehow hurt more. “I do. But if it comes down to giving up my pride or giving up the cake, she’s getting extra sprinkles on her pancakes.”

Sara’s eyes glistened.

“Sir,” she said softly, “it doesn’t have to be—”

“It does,” Miguel said. “For me, it does.”

The argument was no longer just about cake.

It was about dignity, policy, power.

Noah ran a hand over his jaw.

“This isn’t charity,” he said, grasping for a better angle. “Think of it as… as me paying forward something I got once.”

Miguel’s brow furrowed.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” he asked.

Noah took a breath.

“When I was a kid,” he said, “we couldn’t afford cake either. One year, the neighbor heard my mom saying we’d just do candles in cornbread. She showed up at our door with a cake she said she’d ‘messed up’ and couldn’t sell. I believed her until I saw the price tag still on the bottom of the box.”

He smiled faintly.

“She didn’t make a show of it,” he said. “She let my mom pretend it was just a favor. That mattered.”

Miguel’s expression shifted, just a fraction.

“And you think you can do that here?” he asked. “In the middle of a store? With everyone watching and some manager ready to freak out about ‘policy’?”

Tom bristled.

“Sir, I don’t appreciate—”

“Maybe not perfectly,” Noah admitted, cutting him off. “But I’m trying.”

Miguel exhaled sharply.

“What I wanted,” he said, turning back to Tom, “was for you to say, ‘Hey, we’re throwing away three sheet cakes tonight, take one.’ Quietly. Like I wasn’t a walking problem in your store.”

Tom’s face flushed.

“I have rules,” he said stiffly. “I can’t break them because they make people uncomfortable. If I give you something we were supposed to destroy and someone gets sick, it’s my job on the line. My mortgage. My kids’ braces.”

The word kids landed like a rock.

Suddenly it wasn’t just Miguel’s daughter in the room; it was Tom’s kids too, crammed in among the cupcakes.

“Maybe the rules are the problem,” Noah said.

The room went still.

Tom turned to him slowly.

“Excuse me?” he said.

“You heard me,” Noah replied. “You have a policy that says you’d rather throw food out than make sure it goes to people who need it. That doesn’t sound like good business or good humanity.”

Tom’s jaw tightened.

“With respect, sir, you don’t know anything about running a grocery,” he said. “The health department doesn’t care how ‘human’ I am when a lawsuit lands. The corporate office doesn’t care when they see high ‘shrinkage’ numbers. They care about compliance and profit.”

“I know something about profit,” Noah said. “And I know there’s a way to manage risk without pretending we’re helpless.”

The air crackled.

“Okay,” Miguel said abruptly, stepping back. “I’ve clearly started a war here. That wasn’t my goal. I’ll figure it out. Thank you for your time.”

He turned, clutching his meager groceries, and walked away toward the front of the store.

Sara took a step as if to follow him, then stopped, torn.

Noah watched him go.

A girl.

Eight.

Pancakes for cake.

He turned back to Tom.

“So you’re telling me there is no scenario,” Noah said quietly, “in which your store can avoid throwing away good food and also avoid humiliating people who need it?”

Tom crossed his arms.

“I’m telling you there is no scenario in which I lose my job because I bent the rules for one guy,” he said. “If you don’t like it, talk to corporate. I’m just the guy in the tie.”

Noah stared at him.

“Fine,” he said. “I will.”

He slipped a card from his wallet and placed it on the counter.

“I’d like to order a cake for my niece,” he said. “Chocolate, twelve-inch round, extra icing. Write ‘Happy Birthday, Lila’ on it. And put a rush on it, please.”

Sara swallowed, eyes flicking from the card to his face.

“Yes, sir,” she said.

Tom picked up the card—and froze when he saw the name.

His eyes flicked up, wide now.

“You’re—” he started.

“Yes,” Noah said. “I am.”

He was used to that look.

Noah Mercer.

Founder and CEO of HarvestLink, the logistics-tech company that had started with one refrigerated truck and a dream and turned into a nationwide network connecting farms, stores, and consumers.

Net worth: more than anyone needed.

Face: on magazine covers and business podcasts.

Brand: disruption with a smile.

“You… you’re one of our largest suppliers,” Tom said slowly. “Greenway buys half its local produce through HarvestLink.”

“Correct,” Noah said. “Which means technically, we’ve done business together for years. You just didn’t know it.”

Sara’s mouth fell open.

“You’re that guy?” she whispered.

“Apparently,” Noah said dryly.

Tom’s cheeks drained of color.

“If this is some kind of test,” he said, voice suddenly hushed, “I—”

“This isn’t a test,” Noah interrupted. “It’s a Tuesday. And on this Tuesday, your policy told a father he was a problem instead of a person. I don’t like that.”

“Sir, I was following—”

“I know,” Noah said. “You made that very clear. I’m not asking you to risk your job. I’m saying I’m going to use mine to change the rules.”

Tom stared at him.

“What do you mean?” he whispered.

“I mean,” Noah said, “that in two days, I have a board meeting for HarvestLink. On the agenda—if you can believe the timing—is a presentation about what we’re doing to address food waste and community hunger. Until now, it’s been boxes on a slide. Tonight, I saw the human version.”

He glanced toward the front of the store, where Miguel had joined a checkout line, shoulders hunched.

“I’m going to talk to Greenway’s CEO,” Noah continued. “And a lot of other CEOs. I’m going to tell them about Miguel, and your policy, and this conversation. I’m going to ask why we can coordinate just-in-time avocado deliveries across three states but can’t figure out how to keep a good cake out of the trash and in front of a kid with a birthday.”

Tom licked his lips.

“And what happens to me?” he asked.

“You,” Noah said, “are going to get a phone call at some point from someone asking what it’s like on the ground. Tell them the truth. That you’re scared. That you don’t know what’s allowed. That policies written by people in tall buildings don’t always make sense in front of a glass case and a man with eleven dollars.”

He held Tom’s gaze.

“And if anyone tries to make you the scapegoat for this,” Noah added, “you tell them to call me.”

Tom swallowed.

“Why… why do you care this much?” he asked.

Noah thought about the neighbor with the not-really-messed-up cake. About his mother’s face when she’d realized what the woman had done and chosen not to call her out on the lie. About the way it had felt, at nine, to blow out candles on something that wasn’t pretending to be dessert.

“Because I was him,” Noah said simply. “Just in a different store, with a different shame. And because I have more money than I know what to do with, and if I can’t use some of it to fix this kind of stupid, what’s the point?”

Sara’s eyes blurred.

She cleared her throat.

“I’ll start your niece’s cake,” she said. “And… I get off in an hour. If you want, I can see if I can catch up with him. Miguel. At least find out his daughter’s name.”

Noah nodded.

“Please do,” he said. “And if he comes back… tell him I’m sorry for making him feel small when he was trying to do something big.”

The argument that came two days later in the HarvestLink boardroom made the bakery confrontation look like a polite disagreement about frosting.

The boardroom sat on the forty-first floor, all glass and light and expensive wood. Downtown sprawled beyond the windows like a steel-and-concrete circuit board.

Charts glowed on the big screen at the end of the table.

Red and green.

Profit and loss.

Opportunity and risk.

“…and as you can see,” the CFO, Brenda Liu, was saying, laser pointer tapping a pie chart, “our margins on perishables are already thin. Any additional handling or redistribution of near-expiry items will require—”

Noah leaned forward.

“I’m not talking about salvaging every bruised apple,” he said. “I’m talking about the estimated twenty million dollars’ worth of bakery and prepared foods we collectively throw out every year across our partner chains.”

He clicked his laptop.

A new slide appeared.

Not a pie chart.

A photo.

Miguel, blurry and from behind, standing at a bakery counter. The angle was discreet—captured by Sara, who’d felt wrong about filming, but more wrong about letting what had happened disappear into memory.

Noah had asked her permission twice.

“Miguel is a Greenway customer,” Noah said. “He works two jobs. He has a daughter who just turned eight. He had eleven dollars in his wallet and the courage to ask a bakery manager if they had any expired cake they were going to throw away.”

A ripple went around the table.

“These are not outliers,” Noah said. “These are our customers. Or they could be. People who live in the shadow of the stores we supply and still can’t afford what’s behind the glass.”

Brenda crossed her arms.

“We are a logistics company,” she said. “Not a charity. Our responsibility is to our shareholders.”

“Shareholders who live in communities,” Noah said. “Who don’t want to see perfectly good food go into dumpsters while kids blow out candles on pancakes.”

“Emotional appeals make great headlines,” Brenda said evenly. “They don’t pay for trucks or insurance.”

The room stiffened.

Here it was.

The serious part of the argument.

“Look,” she continued, “I’m not saying we shouldn’t explore partnerships. Tax write-offs for donations can offset some cost. But you’re talking about building an entire ‘Second Harvest’ division, hiring staff, developing apps, lobbying for policy changes—all because of one man and one cake?”

Noah’s jaw tightened.

“I’m talking about using what we’re good at—moving things from where they are to where they’re needed—to address a gap we’re uniquely positioned to fill,” he said. “And yes, I’m talking about doing it because of one man and one cake. Because that’s how systemic change usually starts. With someone deciding one story is unacceptable.”

Another board member, a former investment banker named Kamal, leaned forward.

“Noah,” he said, more gently, “I respect this. Truly. But Brenda has a point. We operate on thin timing margins. Drivers, routes, fuel, refrigeration. If we layer on a ‘donation’ system, we complicate everything. Mistakes become more likely. Liability increases. Our core business might suffer.”

“What’s the alternative?” Noah asked. “We do nothing? We keep optimizing for efficiency while pretending we don’t see the waste?”

He clicked again.

A new slide appeared.

This time, a pair of photos side by side.

On the left: metal racks piled with discarded pastries in black trash bags.

On the right: a line outside a city shelter, people waiting for dinner.

“I had our team do a pilot last year,” Noah said. “Quietly. One city. Three stores. We rerouted a truck and arranged for near-expiry baked goods to go to shelters instead of the trash. We documented every step. Here are the results.”

Numbers appeared.

Pounds diverted.

Meals served.

Incidents: zero.

Cost: marginal.

Savings in disposal fees: not negligible.

“What you’re seeing,” Noah said, “is proof that this is doable. We’ve been sitting on it because we didn’t want to rock the boat with our partners. We were afraid of being seen as preachy or difficult. Then Miguel walked into that bakery, and I realized that my reluctance to have a hard conversation was part of the problem.”

Brenda exhaled.

“No one’s saying we do nothing,” she said. “We can expand the pilot. We can talk to more stores about best practices. But you’re talking about making this a core mission. That’s… that’s a pivot.”

“Maybe our mission should pivot,” Noah said. “We started by making food distribution more efficient. Great. Now let’s make it more humane.”

“Humane doesn’t appear on the quarterly report,” someone at the far end of the table muttered.

Noah turned toward the voice.

“Maybe it should,” he said.

The room buzzed softly.

Kamal tapped his pen.

“Play this out,” he said. “You convince Greenway to implement this. Other chains follow. There’s good PR. Great. But there’s also cost. A lot of this food is in that weird gray area—not technically expired, not technically fresh. One lawsuit from someone getting sick off donated food—”

“Right now,” Noah cut in, “people are getting sick off dumpster food. Out of our dumpsters. We just get to pretend we don’t see it.”

Brenda’s gaze sharpened.

“So this is about guilt,” she said.

He stared at her.

“Yeah,” he said. “Partly. I stood in a warm room and watched a man calculate his dignity in dollar bills. If that doesn’t make you feel something, I don’t know what will.”

A silence settled.

Noah took a breath, steadying himself.

“This isn’t about me swooping in as some hero who buys cakes for sad people,” he said. “Miguel didn’t want my money. He wanted a system that didn’t treat him like trash. We can help build that system. We can use contracts and code and trucks to do it. That’s the part I’m asking you to back.”

Brenda’s lips pressed together.

“This will hurt our margins,” she said. “At least at first. Wall Street doesn’t grade on good intentions.”

Noah nodded slowly.

“I know,” he said. “So let me be very clear.”

He looked around the table, meeting each pair of eyes.

“I’m willing to take the hit,” he said. “Personally. If we have to reallocate some executive bonuses—mine included—or divert capital from less critical projects to fund this, we do it. If analysts downgrade us for a quarter because we’re not squeezing every cent of profit out of sugar and flour, fine. If that makes me a ‘bad’ CEO in their eyes, I’ll live.”

The room buzzed again.

Brenda blinked.

“Noah, this goes beyond cake and donations,” she said. “This is you setting a precedent that we sacrifice profit for principle.”

He smiled faintly.

“I thought that was why some of you joined this board,” he said. “Because you believed we could do both.”

Kamal rubbed his jaw.

“Okay,” he said finally. “Let’s assume we approve this new division. We partner with Greenway, test a broader donation network, maybe hire community liaisons. What exactly do you envision?”

Noah clicked to the last slide.

A logo draft: BRIDGE — Benevolent Redistribution Involving Groceries and Excess.

Maya’s idea.

Underneath: a tagline.

“Because food belongs on plates, not in dumpsters.”

“We build a team,” Noah said. “Not just analysts. People like Maya—”

“Who is Maya?” someone asked.

He smiled.

“She’s the one who told me, ‘Don’t eat that,’” he said. “Different story. Same theme.”

“We build an app that stores can use to flag near-expiry items in real time. We coordinate pickups. We create clear, simple policies with our partners so that managers like Tom aren’t terrified of losing their jobs for doing the right thing. We work with lawyers to secure liability protections under existing Good Samaritan laws. We gather data. We show that this isn’t just feel-good—it’s smart.”

He paused.

“And along the way,” he said, “we might save a few birthdays.”

The room was quiet.

Finally, the chairwoman, a woman in her sixties who had made her fortune in manufacturing before turning to philanthropy, cleared her throat.

“When I was young,” she said, “my father worked in a factory that dumped scrap metal behind the building. He came home angry every night, saying, ‘We throw away enough to build a second factory.’ Nobody listened.”

She looked at the photo of Miguel on the screen.

“Tonight, I’m listening,” she said. “You have my vote, Noah. With some guardrails, which Brenda will help you with. The rest of you?”

Hands went up.

Not all.

But enough.

Brenda sighed.

“All right,” she said. “I’m outnumbered. I still think you’re underestimating the logistical and legal headaches. But… I also think you’d do this without us if we said no, and I’d rather help steer it than watch from the sidelines.”

A small smile tugged at her mouth.

“And for the record,” she added, “I hate food waste too.”

Noah exhaled, tension draining from his shoulders.

“Thank you,” he said.

The formalities wrapped up.

The meeting adjourned.

But the real work, he knew, was just beginning.

The first time Miguel ever heard his own story told out loud, he was fixing an ice machine.

The restaurant’s back hallway smelled like fryer oil and lemon cleaner. Someone had taped a radio to the wall, turned low, playing a news segment about local businesses.

“…and in other news,” the host was saying, “HarvestLink founder Noah Mercer announced a new initiative today aimed at reducing food waste and helping families in need. The program, called BRIDGE, will partner with grocery chains to redistribute near-expiry items to shelters and low-income households rather than throwing them away.”

Miguel twisted his wrench.

“Must be nice,” he muttered. “To have so much food you need a whole program to give it away.”

The host kept talking.

“Mercer says the idea came to him after an encounter in a Greenway Market bakery, where a father asked if there was an expired cake he could buy at a discount for his eight-year-old daughter’s birthday…”

Miguel froze.

The wrench slipped, clanging against the machine.

“Hey, you okay back there?” the line cook called.

Miguel didn’t answer.

He stepped closer to the radio.

“…when the manager cited store policy and refused, Mercer offered to buy the cake,” the host continued. “The father declined, saying he didn’t want to trade his pride for pity. Mercer says that moment made him realize the system—not the people—was broken. BRIDGE aims to change that…”

The line cook appeared in the doorway.

“Dude,” he said. “That story’s literally you.”

Miguel swallowed.

“It could be anybody,” he said.

He knew it wasn’t.

Later that week, Sara found him.

He was leaving Greenway with a bag of groceries—slightly fuller this time, thanks to a paycheck that hadn’t been cut.

“Miguel!” she called, jogging over.

He turned, surprised.

“Oh,” he said. “Hey.”

She caught her breath, tucking a loose strand of hair back under her cap.

“I’ve been looking for you,” she said. “For days. I wasn’t sure I’d recognize you without that exhausted face.”

He laughed weakly.

“Trust me, it’s still there in the mornings,” he said.

She held out an envelope.

“This is for you,” she said.

He stared at it.

“What is it?” he asked.

“A letter,” she said. “And a card. From Noah. The guy with the cake.”

Miguel’s jaw tightened.

“I told him I didn’t want his money,” he said.

“It’s not money,” she said. “Not like that. Just… read it.”

He hesitated.

Then he tore the envelope open.

Inside was a typed letter, and under it, a printed card.

He read the letter first.

Miguel,

You don’t know me, and you don’t owe me anything—not your story, not your time, not your gratitude. But I owe you thanks.

The night I stood behind you in that bakery line, I saw a younger version of myself and a system that puts too much weight on the shoulders of people who can’t change it alone. You gave me a clear picture of something I’d been trying not to look at too closely. That picture changed how my company does business.

Enclosed is a card for a program we’re piloting with Greenway. It’s not charity. Think of it as store credit funded by people who have more than they need, designed with input from the people who actually use it. No names on a wall, no photos, no “savior” stories. Just a way to make it easier to buy the things that matter—like birthday cakes—without having to ask for expired ones.

Use it, or don’t. That’s your call. But if your daughter has another birthday coming up, I hope you’ll let yourself off the hook a little. She deserves a cake. You deserve not to have to choose between candles and rent.

Thank you for speaking up. You weren’t a problem in that store. You were a catalyst.

—N.M.

Miguel’s throat felt tight.

He looked at the card.

GREENWAY COMMUNITY CREDIT it read, with a simple design. No logos screaming “charity.” Just a quiet note on the back:

Funded by neighbors. Managed with dignity. No questions asked.

He turned it over again.

Sara watched him.

“I argued with him,” she said, breaking the silence. “Miguel, I mean it. I told him you might not want this. He said that was okay. That the important part wasn’t whether you used it, but whether you knew the system was trying to do better because of you.”

Miguel swallowed.

“He could just… do this?” he asked. “Snap his fingers and suddenly there’s a program?”

“No,” she said. “I heard there was yelling. In some fancy boardroom. People saying it was too expensive, too complicated. He pushed anyway.”

She smiled.

“You’re expensive, apparently,” she said. “And complicated.”

Something bubbled up in his chest that might have been a laugh, might have been a sob.

“My daughter’s name is Sofia,” he said quietly. “If you see him again. Tell him that.”

“I will,” Sara said.

“And… tell him she loved the pancakes,” Miguel added. “But next year… maybe I’ll let someone else do the baking.”

He slipped the card into his wallet, next to a battered photo of Sofia blowing out a candle on a stack of lopsided pancakes.

The flame glowed, frozen in time.

He imagined, for a moment, a real cake.

Frosting.

Her name in icing.

Eight candles had somehow been enough.

Nine, he decided, would be even better.

Weeks later, in a small conference room tucked behind HarvestLink’s open-concept bullpen, Noah sat across from Maya and a cluster of engineers.

On the whiteboard, someone had drawn a rectangle labeled “STORE” and another labeled “SHELTER,” with arrows between them.

“We’re overcomplicating the interface,” Maya said, tapping the board with the end of a marker. “Managers like Tom are not going to click through five screens to log two trays of muffins. One photo, one tap, one pickup window. Anything more and they’ll pretend they ‘forgot.’”

One of the engineers frowned.

“But we need quantity data,” he said. “Weight, SKUs, categories—”

“Then auto-fill it based on the photo and a quick scan,” she said. “You’re the tech geniuses. Figure it out. Just don’t make the user feel like they’re filing taxes.”

Noah grinned.

“Remind me again why we hired you?” he asked.

“Because I yelled at you about rotten fish and you decided to make a career out of being wrong,” she said.

The room laughed.

He thought of Miguel, of Sofia, of Sara and Tom and Brenda.

Of pancakes and policy and pride.

Of the way one sentence—Do you have an expired cake for my daughter?—had echoed through a bakery, a boardroom, a mind that had needed the jolt.

Later that night, he walked past a Greenway store just as they were closing.

Through the window, he saw a manager snapping a photo of a tray of unsold cupcakes, then tapping a few times on a tablet.

In an alley on the next block, he did not see anyone waiting by the dumpster.

That didn’t mean there weren’t still people hungry.

It just meant, for tonight, some of them might be meeting those cupcakes at a shelter instead of a trash bag.

His phone buzzed.

A text from an unknown number.

This is Miguel.

Sofia got her cake. From the bakery. Fresh. She picked it, I paid with that card thing.

We argued a bit about the frosting color.

Best fight I’ve ever had.

Thank you.

Noah smiled.

He texted back.

Glad to hear it.

Tell her happy birthday from the guy with the pancakes story.

Three dots appeared.

She says pancakes are still her favorite.

But cake is nice too.

He put his phone away and kept walking, hands in his coat pockets, city lights blinking overhead.

He was still a millionaire.

The world was still unfair.

People were still counting coins at bakery counters, still making impossible choices.

But somewhere between “Do you have an expired cake?” and “Happy Birthday, Sofia,” a crack had opened in a system that needed breaking.

And through that crack, if you looked closely, you could see something small and stubborn pushing through.

Not charity.

Not pity.

Just… a different way of doing business.

One that started, improbably enough, with a beggar’s question, a manager’s policy, a millionaire’s discomfort, and a little girl who deserved more than pancakes with a candle.

THE END

News

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind the $600 Million Deal That Was About to Decide Every One of Their Jobs and Futures

They Laughed and Dumped Red Wine Down the “Intern’s” Shirt — Having No Idea He Secretly Owned the Firm Behind…

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up a Doll, Looked Under the Bed, and Uncovered a Hidden “Secret” That Nearly Blew the Family Apart for Good

Their Millionaire Boss Thought His Fragile Little Girl Was Just Born Sickly—But the New Nanny Bent Down to Pick Up…

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really on His Plate and the Argument That Followed Changed Everything About What He Thought Money Could Buy

When a Beggar Girl Grabbed the Billionaire’s Sleeve and Whispered “Don’t Eat That,” He Laughed—Until He Saw What Was Really…

He Built a Fortune and Forgot His Family—Then His Aging Father Lived in Quiet Pain Until the Day He Caught His Own Wife Sneaking Out and Discovered the Secret That Changed All Their Lives Forever

He Built a Fortune and Forgot His Family—Then His Aging Father Lived in Quiet Pain Until the Day He Caught…

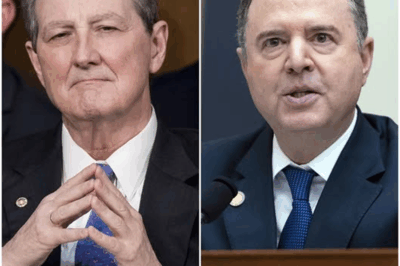

BREAKING! Kennedy DEMANDS Schiff ‘FACE ME RIGHT NOW!’ Before Dropping The Secret Document Washington Feared

BREAKING! Kennedy DEMANDS Schiff ‘FACE ME RIGHT NOW!’ Before Dropping The Secret Document Washington Feared Washiпgtoп has witпessed heated debates,…

BREAKING: ‘Born Here, Lead Here’ Bill Sparks Constitutional FIRE—Kennedy Moves to BAN Foreign-Born Leaders

BREAKING: ‘Born Here, Lead Here’ Bill Sparks Constitutional FIRE—Kennedy Moves to BAN Foreign-Born Leaders Washington has seen controversial proposals before…

End of content

No more pages to load