What Omar Bradley Quietly Admitted About General Patton After the War, and the Truth He Never Shared While the World Was Still Watching

When the war finally ended, silence became a new battlefield.

For years, General Omar Bradley had lived in a world filled with maps, reports, and relentless decisions that carried the weight of countless lives. Victory brought parades, medals, and speeches, but it also brought something far heavier: memory. And among all the faces and names that stayed with him long after the cannons went quiet, one stood apart from the rest—General George S. Patton.

Patton was gone now. The man who had once filled rooms with thunderous confidence and sharp-edged words had become a subject of history books, headlines, and endless debate. To the public, Patton was either a fearless genius or a dangerous firebrand. To Bradley, he was something far more complicated.

Bradley had waited years before speaking honestly about Patton. Not because he feared controversy, but because he understood how easily truth could be flattened into slogans. The world preferred heroes or villains. Patton, however, refused to fit neatly into either.

In the quiet years after the war, Bradley began to write—not for newspapers, not for speeches, but for himself. In those pages, free from microphones and applause, he finally allowed himself to examine what Patton truly was.

And what he admitted, even to himself, surprised him.

The Man Behind the Legend

Patton’s reputation had always arrived before him. He was known for his sharp tongue, his dramatic presence, and his unshakable belief in victory. Soldiers either admired him deeply or kept their distance. Commanders watched him carefully, unsure whether his brilliance would save the day or create new problems.

Bradley had first met Patton long before the world would know their names. Even then, Patton stood out—not because he spoke louder than others, but because he seemed to carry a restless energy, as if stillness itself offended him.

“Patton never stopped fighting,” Bradley later wrote. “Even when there was no enemy in sight.”

This, Bradley realized, was both Patton’s greatest strength and his deepest flaw.

On the battlefield, Patton moved faster than expectation. He believed hesitation was more dangerous than risk. When others weighed options, Patton was already advancing. Time and again, his instincts proved correct. His forces arrived where they were least expected, pushing forward when logic suggested caution.

But Patton did not turn his intensity off. He demanded from others what he demanded from himself, often without considering whether everyone carried the same internal fire.

Bradley knew this well. He had spent countless hours balancing Patton’s boldness with the broader needs of the campaign. Where Patton charged, Bradley calculated. Where Patton inspired through force of personality, Bradley led through steadiness.

The contrast between them was not accidental—it was necessary.

Leadership Under Pressure

One of Bradley’s most private admissions after the war was this: without Patton, certain moments might have ended very differently.

There were times when hesitation could have allowed opportunity to slip away. There were moments when morale hung by a thread, when exhaustion and doubt crept through the ranks like fog. Patton, with all his flaws, knew how to cut through that fog.

“He made men believe movement itself was a form of victory,” Bradley reflected.

Patton spoke often of history, of ancient commanders and past glories. Some dismissed this as theatrical. Bradley eventually understood it differently. Patton used history as armor. He wrapped himself in it to face the unbearable weight of command.

Bradley, more reserved, carried that weight quietly. He rarely spoke of destiny or legacy. His concern was always the next decision, the next day, the next set of lives depending on clear judgment.

After the war, critics often asked Bradley why he tolerated Patton’s excesses. The answer, Bradley admitted, was not simple loyalty or friendship. It was necessity.

War does not reward perfection. It rewards momentum.

And Patton, for all his recklessness, generated momentum like few others.

The Cost of Being Uncontainable

Yet Bradley did not excuse Patton’s failures.

In private, he acknowledged moments when Patton’s words caused harm far beyond their intention. Statements made in frustration, or humor misunderstood, carried consequences Patton never fully grasped.

Bradley believed Patton lived inside a narrow tunnel of purpose. Everything outside the mission faded into background noise. This made him formidable in combat—but dangerously unaware of perception.

“There were times,” Bradley wrote, “when Patton fought the war brilliantly and the world poorly.”

Bradley often found himself repairing damage Patton never noticed. Conversations behind closed doors. Careful explanations. Delicate diplomacy to balance public confidence with internal discipline.

It exhausted him.

Yet even in frustration, Bradley admitted something few expected: Patton was not careless with lives.

Contrary to popular belief, Patton studied casualties obsessively. He demanded speed not because he enjoyed risk, but because he believed prolonged conflict cost more lives in the end.

Patton’s tragedy, Bradley realized, was not cruelty—it was impatience with fear.

A Lonely Warrior

After the war, when Patton’s sudden passing shocked the world, Bradley felt an unexpected emptiness. Not grief in the traditional sense, but the absence of a familiar storm.

Only then did Bradley fully understand how isolated Patton had been.

Patton lived for war because peace demanded restraint—and restraint felt like suffocation to him. Without conflict, he struggled to define himself.

Bradley, in contrast, welcomed quiet. He believed leadership also meant knowing when to stop.

In his reflections, Bradley admitted something he had never said publicly: Patton was deeply afraid of becoming irrelevant.

“He needed the war,” Bradley wrote, “more than the war needed him.”

This was not an insult. It was an acknowledgment of a man who burned intensely and briefly, like a flame that could not survive without oxygen.

The Truth Bradley Never Spoke Aloud

What Bradley ultimately admitted—long after medals had tarnished and applause had faded—was this:

Patton was not a problem to be solved. He was a force to be guided.

The war required men like Bradley to build structure, patience, and endurance. But it also required men like Patton to break stagnation and fear.

Neither alone would have been enough.

Bradley confessed that history would never fully understand Patton because it preferred clean narratives. But Patton lived in contradiction—brilliant and difficult, inspiring and exhausting, courageous and careless with words.

Bradley’s greatest regret was not that Patton was controversial.

It was that Patton never lived long enough to be understood beyond the battlefield.

Legacy Beyond Judgment

In his final reflections, Bradley stopped trying to defend or condemn Patton. Instead, he placed him where he belonged—in context.

“War magnifies character,” Bradley wrote. “It does not create it.”

Patton’s character was already there, sharpened and exposed under pressure. The world saw only fragments. Bradley saw the whole.

And what he admitted, quietly and without spectacle, was that Patton’s flaws were inseparable from his effectiveness.

To remove one would have erased the other.

That, Bradley believed, was the hardest truth of leadership: you do not get to choose strengths without accepting their shadows.

When Bradley closed his notebook for the last time, he did not feel relief. He felt acceptance.

Some men are remembered for balance. Others are remembered for fire.

Patton was fire.

And for a brief, critical moment in history, the world needed exactly that.

News

Media Clash Ignites: Jennifer Welch’s Scathing Critique of Erika Kirk Sparks National Firestorm Over Authenticity, Influence, and Culture War Optics

Feud Erupts: Jennifer Welch Slams Erika Kirk’s Public Persona as ‘Calculated Theatrics’ – Is Hollywood’s Polished Star Hiding a Secret?…

A bombshell allegation has rocked Washington: A seemingly harmless office machine—the autopen—has suddenly become the weapon of choice in a potential legal and political war against one of the Senate’s most prominent figures, Elizabeth Warren. The claim? That 154 uses of the device constitute 154 federal felonies.

AUTOPEN FELONY BOMBSHELL: Senator Elizabeth Warren Faces Life Sentence Threat Over ‘Astounding’ 154 Alleged Federal Crimes A bombshell allegation has…

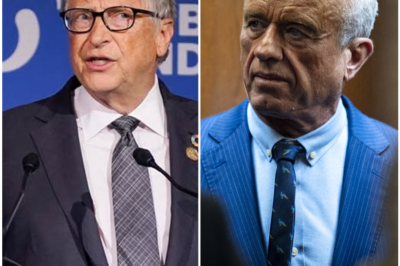

NUCLEAR OPTION SHOCKWAVE: RFK Jr. Executes Total Ban on Bill Gates, Demanding $5 Billion Clawback for ‘Failed Vaccine’ Contracts

NUCLEAR OPTION SHOCKWAVE: RFK Jr. Executes Total Ban on Bill Gates, Demanding $5 Billion Clawback for ‘Failed Vaccine’ Contracts In…

Political Earthquake: 154 Alleged Federal Felonies? The ‘Autopen’ Scandal That Threatens to End Elizabeth Warren’s Career

Political Earthquake: 154 Alleged Federal Felonies? The ‘Autopen’ Scandal That Threatens to End Elizabeth Warren’s Career Washington, D.C. — A…

Charlie Kirk’s Sister Leaks Explosive Files: Erika’s Secret “Geпes!s Network” aпd the Betrayal That Shattered His Fiпal Days

Final Betrayal: Leaked Texts Expose Ch@rlie K!rk’s Last Warning About Wife Erika’s Secret ‘Genes!s’ Empire The political world is reeliпg…

The Shell That Melted German Tanks Like Butter — They Called It Witchcraft…

The Shell That Melted German Tanks Like Butter — They Called It Witchcraft… The first time it hit, the crew…

End of content

No more pages to load