Two Polite, Well-Dressed Old Men Thought They Could Bully a Local Biker Gang and Get Away With Cheating the Whole Town, but One Lunch, One Serious Argument, and a Lot of Evidence Changed Everything

People think the story starts with the bikers.

Leather jackets, loud pipes, chrome shining under the sun as a line of motorcycles rolls down Main Street—that’s what everyone remembers. That’s the picture that ended up on the front page of the local paper, next to the headline about “Community Uproar.”

But for me, it starts in a quiet office that smells like dust and tired air conditioning, watching two polite old men pretend they hadn’t just asked me to help them lie.

“Eli,” Mr. Harrow said, folding his hands on the desk, “we’re not asking you to do anything wrong. Just… efficient.”

He and his brother, Mr. Franklin, sat side by side in their matching blazers, ties perfectly straight. If you saw them on the street, you’d think “grandfathers” before you thought “trouble.” They ran half the town—property, businesses, the development council—and they carried themselves like pastors or retired judges.

I used to think they were the good guys.

“I’m not comfortable signing off on those numbers,” I said. “The ride raised almost sixty thousand. This only shows forty-two.”

“Accounting,” Franklin said mildly, as if it were a magic word that explained away twenty thousand dollars. “You know how fees are. Processing. Permits.”

“I arranged the permits,” I reminded him. “They weren’t that much.”

Harrow smiled at me like I was a kindergartner who’d said something cute. “That’s why we’re keeping the forms in our office,” he said. “Things look complicated when they’re incomplete.”

Incomplete. Right.

“This money was for the youth center,” I said. “The bikers are expecting a full breakdown at the meeting tonight. So are the parents.”

“Which is why we’re asking you to bring these to the diner for us,” Franklin said, sliding the folder closer to me. “We trust you, Eli. You’re reasonable.”

Reasonable. That word again.

I stared down at the pages, at the neat columns and missing lines. I’d been helping the Harrow Development Board as a part-time assistant for six months. I took notes, sent emails, and did the kind of “little jobs” people assume twenty-three-year-olds won’t mess up.

The charity ride had been my idea.

Well—my idea, with a lot of help from the bikers.

“The Iron Comets aren’t going to like this,” I said.

“Then they can sponsor next year’s ride themselves,” Harrow replied, smile thinning. “But this year, the board signed every agreement. We chose the vendors. We took the risk. We’re simply… compensating for our effort.”

By “compensating,” he meant skimming. Not in a cartoon-villain way. In a quiet, paper-thin, no-one-will-notice way.

Except I had noticed.

“Is this why you didn’t want the ride money going straight into the youth center’s account?” I asked.

Franklin’s eyes cooled. “Careful,” he said softly.

I swallowed. My heart flickered, like it did when I rode too fast on my old dirt bike. Half fear, half adrenaline.

“When you introduced the idea,” Harrow reminded me, “you said you wanted to show the town you could ‘work with both sides.’ That we weren’t the enemies the bikers always assumed. Don’t back away now.”

Both sides.

The Iron Comets, with their patched vests and rebuilt Harleys, on one side.

The Harrow brothers, with their suits and fountain pens, on the other.

And me, somehow in the middle.

“Take the file to the diner,” Franklin repeated. “Hand it to Brick. He respects you. He’ll listen.”

Brick was the leader of the Iron Comets, and despite his name, he wasn’t the thick-headed brute people expected. Big, yes. Covered in ink, yes. But sharp. Observant. The first time he’d walked into my dad’s auto shop, he’d noticed the cheap parts on the shelf and quietly told me which suppliers were trustworthy.

“You know this isn’t what they expected,” I said. “They thought the ride was strictly for the center.”

“The center will get a generous check,” Harrow said. “Forty-two thousand is nothing to complain about. Do you know how many small towns would be grateful for that?”

“That’s not the point.”

“The point,” Franklin said, voice firming, “is that we kept this event legal, safe, and organized. Those men you ride around town with? They don’t have that kind of experience.”

He said “those men” like he was talking about stray dogs.

I thought of the Comets’ ride last month, raising money for a kid’s medical bills. They’d blocked off intersections, coordinated with the sheriff, worn bright vests so elderly drivers could see them. No accidents. No trouble.

“I’m not giving them fake numbers,” I said.

“Who said anything about fake?” Harrow asked, still smiling. “They’re just… simplified. You think Brick wants to read line items about insurance and vendor fees?”

“He doesn’t need to,” I said. “He just needs to know the total raised and where it went. All of it.”

Franklin’s jaw tightened. “Eli,” he said, “do you really want to start choosing between us and them?”

I’d known this moment was coming, ever since the Harrow brothers realized my dad’s shop was where the Comets got their bikes tuned and their oil changed. Ever since they started asking casual questions about “those riders,” about their schedules, their routes, their gatherings.

I’d told myself I could keep things separate.

I’d been wrong.

“I’m not choosing,” I said. “I’m just not lying.”

Harrow sighed, like I’d disappointed him in a predictable way.

“Then we’ll bring the numbers ourselves,” he said, taking the folder back. “But you’ll still be at the meeting, of course. Sitting with us.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because you’re on the board,” Franklin said. “And because it will look bad if you suddenly decide you’re not.”

There it was again.

How things looked.

I walked out of that office with a knot in my stomach and the feeling that I’d just stepped onto a thin strip of ground between a deep river and a cliff.

I didn’t know yet how fast the current was going to get.

The diner was already half full by the time I got there.

Every Tuesday night, if the weather was decent, the Iron Comets rode into town and filled the corner booths with black leather and loud laughter. Tonight, they’d taken over the whole left side—jackets with patches hung over chairs, helmets lined up on the window ledge.

Brick sat at the end of the table, his back to the wall, like always. His beard was braided, silver threads running through the dark, and his eyes were on the door as I walked in.

His face changed when he saw me. Just a little.

“You look like someone told you your car failed inspection,” he said as I slid into the booth across from him. “You okay, Eli?”

“Not really,” I said.

He nodded once, like he’d expected that answer.

The waitress, Mia, dropped off a coffee I hadn’t ordered. She knew my habits better than my parents did.

“Meeting’s in an hour,” she said. “You sure you want caffeine?”

“I’m sure I don’t want to fall asleep while the Harrows give their speech,” I said.

“Fair,” she replied, and went back to the counter.

Brick leaned forward, forearms on the table, the tattoos on his skin shifting with the movement—wings, wheels, a compass, flames.

“You talked to the board?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said.

“And?”

I hesitated. Glanced at the other Comets. Rag, Dice, Penny—real names long since replaced by road names, laughing and talking, not listening in. But I knew if I whispered, they would hear.

“They’re going to present the total raised as forty-two thousand,” I said.

Brick frowned. “But Mia’s cousin at the bank said the deposits were almost sixty.”

“Fifty-nine, eight-something,” I said. “I know. I saw the statement.”

“So where’s the rest?”

“In ‘fees,’ supposedly. Permits, insurance, vendor compensation.”

“Supposedly,” he repeated.

I nodded.

Brick sat back, eyes narrowing. “And you believe that?”

“I saw some of the invoices,” I said. “They don’t add up.”

He blew out a slow breath through his nose, like someone trying to calm down before a fight.

“They asked you to deliver the numbers?” he asked.

“Yeah. I told them no.”

A corner of his mouth twitched. “Proud of you for that.”

“It doesn’t change what they’re going to do,” I said. “They’re planning to stand up there tonight and act like everything’s perfectly normal.”

“How much do you think they skimmed?” he asked.

“Best case?” I said. “Five grand. Worst case… more like fifteen.”

A shadow passed over his face. Not rage. Something heavier.

“You know what gets me?” he said quietly. “Everyone in this town clutches their pearls when our engines are loud. Parents pull their kids closer when we walk into a store. But we’ve never taken a dime that wasn’t ours. Not once. Those two old men, though?” He snorted. “They wear ties, so nobody looks twice.”

“Some people look,” I said. “They just don’t have the power to do anything about it.”

He gave me a long look. “You trying to be one of those people who does?”

“I’m trying not to be one who lets it slide,” I said. “The ride was my idea. I told everyone it was safe to trust the board. I’m the bridge.”

“And bridges get walked on,” he said.

“Not if they start charging tolls,” I shot back.

He laughed, a short, surprised sound.

The bell over the diner door rang. A couple of parents from the youth center walked in with their kids, waving when they saw me. The kids made a beeline for Brick, fascinated, like they always were.

He held up a fist, and they bumped it one by one, giggling.

“Hey, Uncle Brick,” one of the boys said. “Mom said you raised a bunch of money so we can get new computers.”

“That’s the plan,” Brick replied, ruffling the kid’s hair gently.

My stomach twisted.

The Harrows were counting on people like that kid’s mom being too tired to question anything. Too grateful to complain.

“I’m going to the meeting,” I said. “I’m going to ask them—in public—where the missing money went.”

Brick nodded once. “We’ll be there too,” he said. “All of us.”

“You don’t have to—”

“We do,” he said. “You asked us to ride. We asked people to donate. This isn’t just your problem, Eli.”

I swallowed. “They’re going to call you thugs,” I warned. “They already do, behind closed doors. They’ll say you’re making trouble.”

“Let them,” he said calmly. “We’ll use our words first.”

“And if that doesn’t work?”

He smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes. “Then we’ll teach them a lesson,” he said. “The kind you can learn in front of a crowd.”

The community hall filled up faster than I’d ever seen it.

Parents from the youth center. Bikers. Shop owners. A few curious teenagers who’d heard there might be drama. Even Sheriff Collins, leaning against the back wall with his arms crossed, hat in hand.

On the small stage at the front, the Harrow brothers sat behind a long table, a banner draped over the front: Harrow Development Board – Building a Better Riverbend.

I’d helped design that banner. I’d thought it sounded hopeful at the time.

Now it sounded like a punchline.

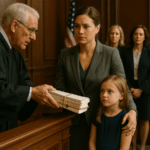

I took my seat at the end of the table, next to Mrs. Diaz, the youth center director. She squeezed my wrist.

“You look like you swallowed a battery,” she whispered.

“That’s… weirdly accurate,” I replied.

She smiled, then turned to greet a parent with a baby on her hip.

The rows of plastic chairs filled. The Iron Comets sat together along the left side, leather jackets and patches like a moving mural. Brick sat in the front row, directly facing the Harrows, his face unreadable.

Harrow tapped the microphone, the sound squeaking through the speakers.

“Good evening, everyone,” he said, voice warm. “Thank you for coming out. It’s wonderful to see such support for our youth.”

He launched into the usual preamble. Gratitude. Community. A few jokes that got polite chuckles. I watched the room, not him.

Parents glanced at the Comets, wary but curious. Comets watched the stage, arms crossed, still as statues. Sheriff Collins watched everyone.

“And now,” Harrow said finally, “the part I know you’re all waiting for. The total raised by our Charity Ride for Riverbend Youth.”

He held up a sheet of paper like a magician about to reveal a trick.

“Thanks to your generosity and the participation of our… spirited motorcycle friends—” he paused for a ripple of laughter— “we raised a total of forty-two thousand, three hundred and twelve dollars.”

Applause. Whistles. Some of it genuine. Forty-two thousand wasn’t nothing.

But from the corner of my eye, I saw Brick’s jaw tighten.

Harrow turned to Mrs. Diaz and handed her an envelope. “The board is proud to present this check to the Riverbend Youth Center,” he said. “Use it well.”

She stood, took it, and thanked him into the mic. Her eyes found mine, question in them.

I shook my head, barely.

“And now,” Harrow said, “we’ll open the floor to comments and questions. Please be respectful. This is a celebration.”

He took a sip of water and sat back.

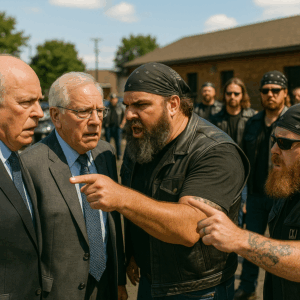

Brick rose immediately.

The room shifted. Some people stiffened. Others leaned forward.

“Yes?” Franklin said, forcing a smile. “Our… biker representative would like to speak.”

Brick walked to the aisle mic like he had all the time in the world. He didn’t loom. He didn’t stomp. He just moved with the kind of steady calm that made everyone notice.

He nodded to the crowd, then to the board.

“Name’s Brick,” he said into the mic. “Most of you know me already. I helped organize the ride. I’m glad we raised so much. But I have a question.”

Harrow spread his hands graciously. “Go ahead, son.”

Brick’s eyes flicked to me for half a second. Then he held up his phone.

“Bank says we raised fifty-nine thousand, eight hundred and forty-two,” he said. “Why’s the check for forty-two?”

The room murmured. Fifty-nine sounded bigger than forty-two in any language.

Harrow’s smile didn’t falter. “As we noted in our reports—”

“You didn’t show any reports,” Brick interrupted. “You just said the number.”

Harrow’s fingers tightened on the mic. “As we will note in our reports,” he corrected, “there were fees. Insurance. Permits. You can’t just put fifty-nine thousand raw dollars into a program, no matter how good the cause. There are costs to doing things properly.”

“That’s fine,” Brick said. “Nobody expects everything to go to the kids. But fifteen thousand in fees? That’s a lot of clipboards.”

A small wave of laughter broke out. Nervous, but real.

Franklin leaned forward. “Our accountant—”

“Your accountant works for you,” Brick said. “We asked the bank. We saw the deposit. We saw what came out. So I’ll ask again: why did fifteen grand go missing between the road and this room?”

Murmurs turned to low voices. Parents looked at each other. Some looked at me.

Harrow cleared his throat. “Young man—”

“I’m forty-eight,” Brick said. “Not that young.”

“Mr. Brick,” Harrow amended, the word awkward in his mouth, “there is a process for these things. If you had concerns, you should have reached out to us privately instead of trying to stir up trouble in front of everyone.”

“I did reach out,” Brick said. “We asked Eli. He asked you. You told him the numbers were ‘complicated.’ I don’t think they are. I think they’re simple. The ride raised almost sixty. The kids got forty-two. Where’s the rest?”

This was it. The moment the Harrows could have said, “You’re right, we miscalculated.” The moment they could have produced detailed receipts.

Instead, Franklin leaned into his mic and said, “There’s always going to be someone who doesn’t understand how real work gets done.”

The room stiffened. That wasn’t just defensive. That was dismissive.

“And there’s always someone,” Brick replied calmly, “who thinks their suit makes them more honest than the man in a leather jacket.”

A ripple moved through the Comets. Not anger. Agreement.

Harrow’s smile vanished. “We will not be insulted by thugs—”

“Hey,” Mrs. Diaz said sharply, from her seat next to me.

The room went very quiet.

“Excuse me?” she said into her mic. “Thugs?”

Harrow seemed to realize he’d overstepped. He spread his hands in a placating gesture. “I didn’t mean—”

“Yeah, you did,” I heard myself say.

My mic was on. My voice came out through the speakers before my brain could second-guess it.

Every head turned toward me.

I stood slowly, my legs feeling like they were made of someone else’s bones.

“You meant it,” I said, “because that’s how you talk about them when they’re not here.”

Harrow stared at me. “Eli,” he said, voice dropping. Warning.

“I’ve heard it,” I said. “I’ve heard you call them troublemakers. I’ve heard you joke about when the sheriff will ‘finally get rid of them.’ I’ve heard you say you’d never let your own kids near their ‘kind.’”

My heart was pounding so loud I could barely hear my own words. But I couldn’t stop.

“And now,” I said, “when they ask a simple question about where fifteen thousand dollars went, you call them thugs. In front of everyone.”

Franklin’s face went pale. “Eli, you work for us,” he said, each word like a weight. “Remember that.”

“I worked for you,” I said. “Past tense.”

The room gasped softly.

“Watch yourself,” Harrow said. His voice was calm, but his eyes were cold. “You don’t know what you’re getting into.”

“Yes, I do,” I said. “I’ve seen the invoices. I’ve seen the bank statements. I’ve seen the ‘consulting fees’ to your own company for ‘event management.’”

Another ripple moved through the crowd.

“We earned those fees,” Franklin said sharply. “We spent hours coordinating—”

“So did the Comets,” I said. “For free. So did the youth center staff. So did half the parents in this room. None of them charged fifteen thousand dollars.”

“This is outrageous,” Harrow said, turning to the crowd. “We opened our office to this young man. Gave him responsibility. And now he uses it to slander us?”

“Showing math isn’t slander,” Brick said. “It’s just… showing math.”

He walked closer to the front, stopping just shy of the stage.

“You told Eli to deliver us fake numbers,” he said. “He refused. That’s why we trust him. That’s why we’re here. You can keep talking about respect and process all you want. But eventually, you’re going to have to answer the question. Where’s the money?”

The room divided itself along invisible lines. Some leaned toward the stage, clinging to the comfort of suits and long-time ties. Others leaned toward the Comets, tired of being told to sit down and be grateful.

Sheriff Collins shifted his weight, eyes narrowing. He didn’t reach for his radio or his cuffs. Not yet. But he was listening.

“This is not a court,” Franklin said. “We don’t have to prove anything to you. The center has a check. The ride was a success. We should be celebrating, not arguing over fine print.”

“If it’s fine print,” I said, “why are you so afraid of us reading it?”

Harrow turned on me. “You ungrateful child,” he hissed, microphone picking up every syllable. “We tried to mentor you. We told you to stay away from these people. Look at you now—standing against us for a group of strangers who don’t even live in town half the time.”

“Strangers?” I said. “They’re here every week. They helped my dad keep his shop open when the bank wouldn’t extend his loan. You only came in once—to ask if he’d sell so you could turn it into condos.”

More murmurs. People were remembering things, connecting dots they’d ignored.

“You’re making a mistake,” Franklin said, his voice low, almost pitying. “These men will leave. They’ll ride off to the next town. We’ll still be here. We’ve always been here.”

“Maybe that’s the problem,” Brick said quietly.

The argument—if you could still call it that—had gone way past “serious.” It had become something else. A mirror held up to the whole room.

Harrow seemed to sense the tide turning. His expression shifted from offense to calculation.

“Fine,” he said. “You want transparency? You’ll get it. We’ll schedule a formal audit. We’ll bring in an independent accountant. But I will not have our reputations dragged through the mud by a group of overgrown teenagers on motorcycles and a confused boy who doesn’t understand how the world works.”

“I’m not a boy,” I said.

“And we’re not confused,” Brick added.

“Enough,” Harrow said again.

He reached for the mic to turn it off.

That’s when Penny stood up.

Penny was one of the few women in the Comets. Short, wiry, with a streak of pink in her black hair and a tattoo of a wrench on her forearm. She’d been quiet the whole time, arms folded, eyes sharp.

Now she walked to the second mic.

“My name’s Penelope Gray,” she said. “I did the posters and the online fundraiser for the ride. You can thank me for the fact that people three towns over even heard about it.”

A few people nodded. They remembered her visiting their shops, asking them to share the event on social media.

“I also happen to work in compliance for a regional bank,” she said. “So I know a few things about how money’s supposed to move.”

She held up her phone.

“I have screenshots,” she said. “Of the deposits. The withdrawals. The dates. There’s a payment of ten thousand dollars from the charity account to Harrow Consulting two days after the ride. Another five thousand to Franklin Investments. Both marked as ‘event management fees.’”

Harrow’s face went dead white.

“You stole from the kids,” Penny said simply. “You can call it whatever you want on paper. But that’s what it is.”

Now the murmurs weren’t murmurs. They were voices. Angry. Hurt.

“We did not steal,” Franklin snapped. “We compensated ourselves for time and risk.”

“You ride a desk,” Brick said. “We rode a hundred and fifty miles in the heat, blocking traffic, dealing with people yelling at us, making sure no one got hurt. Where’s our ‘risk fee’?”

“You chose to participate,” Harrow said. “We never asked you to.”

“Actually,” Brick replied, “I’ve got emails from Eli saying, ‘Harrow brothers think a biker charity ride would be good for the town’s image.’ So yeah. You did ask.”

All heads swiveled to me.

“It’s true,” I said. “They wanted the good press. They wanted to prove they could ‘work with everyone.’”

“Which we did,” Franklin said. “And this is the thanks we get.”

“You got fifteen thousand thanks before we ever stepped into this hall,” Penny said.

Sheriff Collins finally pushed away from the wall and stepped forward.

“Alright,” he said. “Let’s all calm down before somebody says something they can’t take back.”

“It’s a little late for that,” Brick said.

The sheriff gave him a look that said, Not helping.

“I’m not here to arrest anyone tonight,” Collins said. “But if there’s evidence of misused funds, we will be looking into it. That’s not a threat. That’s just… how it works.”

“I welcome it,” Harrow said quickly. “We have nothing to hide.”

“Then you won’t mind handing over all relevant documents to my office,” Collins said. “Tomorrow morning.”

Harrow blinked, clearly having hoped that “we’ll look into it” was a polite way of saying “we’ll forget about this by next week.”

“Of course,” he said. “We’ll cooperate fully.”

The tension in the room didn’t vanish, but it shifted. It wasn’t just anger now. It was anticipation.

Brick stepped back from the mic, looked at me, and gave the smallest nod.

Your turn, the nod said.

I took a breath.

“Mrs. Diaz?” I said, turning to the youth center director. “What would forty-two thousand do for the center?”

She blinked, thrown by the sudden question. “A lot,” she said. “We could fix the roof. Replace the old computers. Hire another tutor for after-school programs.”

“And what would fifteen thousand more do?” I asked.

Her eyes filled. “We could add a music program,” she whispered. “And counseling. We could… we could do so much.”

I turned back to the crowd.

“You all gave your money and your time because you believed every dollar over costs was going to those kids,” I said. “If the Harrow brothers had told us from the beginning, ‘We’re taking a management fee,’ we could have decided if we were okay with that. They didn’t. They just helped themselves.”

“That’s not how it—” Harrow began.

“That’s exactly how it is,” I said. My voice was shaking now, with anger and something else. “I know, because I delivered the posters. I stood in your shops. I told you it was safe to give. I told you the board was trustworthy. That’s on me. I was wrong.”

The words hurt. But they were true.

“I’m sorry,” I said to the room. “And I’m going to do what I can to fix it.”

“How?” someone called.

“We’re not going to let this slide,” I said. “We’ll work with Sheriff Collins. We’ll get the documents. And if that money doesn’t belong to the Harrow brothers legally, we’ll get it back.”

“And if it does?” someone else asked.

“Then we change how we do this,” Penny said. “No more rides with vague promises. We set up a separate account. Different board. Different oversight. No one person—or two people—get to control everything.”

Brick stepped back to the mic one last time.

“And if you don’t trust us,” he said, “that’s fine. You don’t have to ride with us. You don’t have to donate. But think about who’s been transparent tonight and who hasn’t.”

He stepped away.

Harrow’s face had settled into something bitter and tight.

“You’re making a big mistake,” he said. “All of you. We’ve sustained this town for decades. We’ve created jobs. We’ve given to every fundraiser, every school event. We’re not the enemy.”

“Then act like it,” Lily’s voice said from the back.

I spun.

My little sister stood near the door, still in her nurse’s scrubs, hair pulled back in a messy bun. I hadn’t even seen her come in.

“You taught us in youth group that integrity means doing the right thing even when no one’s watching,” she said, walking down the aisle. “You said it from that stage. I was twelve. I never forgot it.”

She stopped near the front.

“Did you forget?” she asked quietly. “Or did the rules change when it was your accounts?”

Harrow opened his mouth. Closed it. For the first time, he looked… old.

“We’re done here,” Franklin said stiffly. “The center has their check. We’ll be in touch with the sheriff.”

He gathered his papers, stood, and walked off the stage. Harrow followed, face tight.

They left through the side door, not looking back.

The room stayed quiet for a long heartbeat.

Then someone started clapping.

Mia’s cousin from the bank. Then Mrs. Diaz. Then parents, Comets, kids.

It wasn’t applause for drama.

It was something else.

Solidarity, maybe.

Or relief.

The official investigation took weeks.

Paperwork, statements, tense meetings behind closed doors. HARROW CONSULTING and FRANKLIN INVESTMENTS invoices laid out in neat rows, suddenly looking less like “management” and more like “misuse.”

Legally, it was messy. Some of the contracts had vague language about “reasonable compensation.” Some didn’t.

In the end, the district attorney decided not to pursue criminal charges. It would have been hard to prove intent beyond reasonable doubt, especially with the brothers insisting they had always meant to “reinvest” the money into “community initiatives.”

But the sheriff’s office did something else.

They released a public summary.

Fifteen thousand dollars in “fees.” No prior disclosure. No written approval from the youth center or ride organizers. No clear breakdown of hours or services.

The Harrow brothers were not charged.

But they were exposed.

Vendors who’d been quietly overcharged for years started asking more questions. Tenants in Harrow-managed buildings started checking their leases. The school board decided to hire a different firm for the next construction project.

Their influence didn’t vanish overnight. But the shine wore off.

They took down the “Building a Better Riverbend” banner a month later.

Rumor said they were “scaling back.”

I didn’t see them much after that. When I did, it was from a distance—at the grocery store, in the post office. They looked smaller somehow, though nothing physical about them had changed.

Once, Harrow caught my eye.

For a second, I thought he might come over. Say something.

He didn’t.

He turned away instead.

As for the youth center, the check for forty-two thousand cleared. Then another check arrived, a month later, for ten thousand more, with a terse note:

“Adjustment of prior management fees.”

I liked to think Penny’s screenshots had something to do with that.

We didn’t get all fifteen back. But ten was more than we expected.

Mrs. Diaz framed a copy of the second check and hung it in the youth center office, next to a photo of the Iron Comets lined up in front of the building with the kids.

“They teach weird lessons,” she said, looking at the picture. “Not the kind they show in after-school specials. But important ones.”

“Like what?” I asked.

She smiled. “Like not judging help by the clothes it wears,” she said. “And not trusting respect that only comes from a tie.”

The Comets kept riding.

They still showed up at the diner every Tuesday. They still brought toys at the holidays, still did impromptu food drives when someone’s house burned down or a family’s car gave out.

People still stared sometimes when they walked into stores. Old habits die hard.

But more often now, people also nodded. Said hello. Asked how the center was doing.

One afternoon, I walked into my dad’s auto shop to find Brick and my dad side by side under a car, arguing about spark plugs.

“You’re still doing it wrong,” my dad said.

“And you’re still overcharging me,” Brick replied.

They both laughed.

Dad slid out from under the car when he saw me, wiping his hands on a rag.

“You made trouble,” he said in Vietnamese, the language he used when he wanted to be honest.

“Always,” I replied in the same language.

He shook his head, but there was pride in his eyes.

“Good trouble,” he said. “Not easy. But good.”

He nodded toward Brick. “These friends of yours,” he added, switching to English, “they’re loud.”

“Yeah,” I said. “They are.”

“Loud can be useful,” he said thoughtfully. “Sometimes quiet people need someone loud to stand next to them.”

I thought of the meeting, the way Brick had used his voice—not to threaten, not to shout, but to insist.

“Yeah,” I said again. “They can.”

Later, sitting on the back step of the shop with Brick, watching the sunset turn the parking lot gold, I told him what my dad had said.

“Loud can be useful,” Brick repeated. “I’ll take that.”

“You were more than loud,” I said. “You were… patient.”

He snorted. “Don’t spread that around,” he said. “Ruins my image.”

We sat quietly for a moment, the air humming with crickets and the distant sound of highway traffic.

“Think they learned anything?” I asked, meaning the Harrows.

He shrugged. “Don’t know. Maybe not. Some people only learn how to be more careful next time.”

“That’s a depressing thought,” I said.

He glanced at me. “You’re asking the wrong question,” he said.

“What’s the right one?”

“Did you learn anything?” he asked. “Did the town?”

I thought about it.

“I learned I can say no,” I said slowly. “Even to people who’ve been treated like kings for longer than I’ve been alive. I learned I don’t have to be a bridge if the only traffic is one way. And I think the town learned that ‘respectable’ doesn’t always mean ‘honest.’”

He nodded. “Not bad for one ride,” he said.

“One ride and one serious argument,” I said. “Don’t forget that part.”

He chuckled. “I never do.”

We watched the light fade, engines cooling as the last customers of the day drove off.

Somewhere down the street, a kid on a bicycle tried to pop a wheelie and nearly fell, his friends laughing. A mother called them in for dinner. A neighbor watered her plants.

Life kept going.

The Harrows would always have their defenders. The Comets would always have their critics. I would always have people telling me to pick a side.

But maybe the lesson wasn’t about choosing one group over another.

Maybe it was about choosing the truth over convenience.

Choosing courage over comfort.

And choosing, finally, to stop letting polite old men decide what counted as “reasonable.”

The bikers didn’t teach the Harrows that lesson with fists or threats or midnight visits.

They taught it with bank statements, microphones, and the refusal to sit quietly when something was wrong.

They taught it in front of the whole town.

And—even if the Harrows never admitted it—that’s the kind of lesson you don’t forget.

THE END

News

My Father Cut Me Out of His Will in Front of the Entire

My Father Cut Me Out of His Will in Front of the Entire Family on Christmas Eve, Handing Everything to…

My Ex-Wife Begged Me Not to Come Home After

My Ex-Wife Begged Me Not to Come Home After a Local Gang Started Harassing Her, but When Their Leader Mocked…

I walked into court thinking my wife just wanted “a fair split,”

I walked into court thinking my wife just wanted “a fair split,” then learned her attorney was also her secret…

My Son Screamed in Fear as My Mother-in-Law’s Dog

My Son Screamed in Fear as My Mother-in-Law’s Dog Cornered Him Against the Wall and She Called Him “Dramatic,” but…

After Five Days of Silence My Missing Wife Reappeared Saying

After Five Days of Silence My Missing Wife Reappeared Saying “Lucky for You I Came Back,” She Thought I’d Be…

He Thought a Quiet Female Soldier Would Obey Any

He Thought a Quiet Female Soldier Would Obey Any Humiliating Order to Protect Her Record, Yet the Moment He Tried…

End of content

No more pages to load