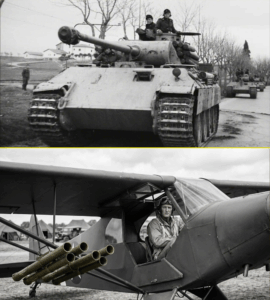

Trapped Infantry Watched German Tanks Close In—Then a Young US Pilot Rigged a “Six-Tube Trick” to His Fragile Paper Plane, Dove Through Fire, and Knocked Out Six Panzers to Save 150 Men

The first time Lieutenant Jack Mallory saw a Panzer up close, he wasn’t sitting in a cockpit.

He was lying in a ditch.

Mud in his mouth. Heart in his throat. The ground shaking under him like some angry giant was stomping across the French countryside.

He’d been a brand-new artillery forward observer then, down with a rifle company trying to help walk shells onto an enemy column. One moment he was peering through his binoculars at a distant speck on the road. The next, that speck had grown fenders and treads and a black cross on its side.

He’d never forgotten the sound.

Not the roar of the engine. Not the crack of the main gun.

The sound that stuck with him was the clatter of tracks and the grinding of gears, that heavy, deliberate clank that seemed to say: I get to choose who lives on this field. Not you.

It wasn’t fear, exactly. It was something colder.

Helplessness.

A year later, strapped into the left-hand seat of a light liaison aircraft the ground troops called a “paper plane,” Jack still heard that sound sometimes when he woke up too fast.

Now, though, he had a different vantage point.

He could see those steel beasts from above.

And, on one insane afternoon in the late fall of 1944, he’d finally get a chance to talk back.

That afternoon started out quiet.

Too quiet, as Sergeant Tom Riley, the battalion radio operator, would’ve said if he’d been the type to indulge in movie lines.

Instead, he just squinted at the sky and checked his watch.

“Mallory’s late,” he muttered.

“There’s fog over the rear areas,” Captain Ben Crowe said, half to himself, half to anyone listening. “Airstrip’s probably socked in. He’ll be here.”

They were dug in along a hedgerow north of a nameless French village, one of a hundred charcoal smudges on a map that seemed to be all smudges lately. The battalion had pushed ahead faster than the plan, chasing rumors that the opposing armor was pulling back to new lines.

Rumors, in war, were like weather reports.

Sometimes accurate. Sometimes completely off.

This time, they were completely off.

Private Eddie Ross, who’d joined the unit two weeks ago and still flinched at loud doors, leaned against the inside wall of a shallow foxhole and tried to pretend his legs weren’t shaking.

“Six tubes,” he said quietly, more to himself than to his foxhole mate. “He really has six?”

Corporal Sam Hernandez, who’d been fighting long enough that his nerves had gone past shaking to a sort of steady hum, smirked.

“That’s what I heard,” he said. “Took a bunch of bazooka launchers, strapped ’em under his wings. ‘Six-Tube Trick,’ he calls it.”

“That legal?” Eddie asked.

Sam shrugged.

“Out here? Legal is whatever keeps you breathing,” he said.

Eddie chewed on that.

He didn’t know much about artillery liaison planes except that they were small, slow, and made of fabric and hope. The first time he saw one, he’d thought it was some farmer’s crop-duster that had taken a wrong turn.

They called them Grasshoppers, L-Birds, Piper Cubs.

Or, more often, paper planes—because that’s what they looked like in a sky where big, tough fighters and bombers roared overhead.

“You think those little pipes can really knock out a tank?” Eddie asked.

“They say he’s nailed three already,” Sam said. “Two parked, one moving. I saw one myself. Hit it on the side road by the orchard. Thing just stopped like it remembered an appointment somewhere else.”

Eddie was trying to decide if that made him feel better or worse when the first distant boom rolled over the fields.

Not theirs.

Theirs was a deeper sound, a heavy thump from somewhere miles behind them.

This one was sharper, nearer.

Then another.

Closer.

“Captain,” Riley called, lifting the handset of his radio. “We’ve got movement on the net. First platoon says they see armor.”

Crowe’s jaw tightened.

“Where?” he asked.

Riley listened, pencil moving on a map.

“Tree line east,” he said. “Two, maybe three tanks at first. Now more. They’re cutting off the road behind Able and Baker. If they keep pushing, we’re the next course.”

Crowe swore under his breath.

“Artillery?” he asked.

“Firing elsewhere,” Riley said. “They’re trying to knock out a bridge six miles south. They can give us harassment rounds, but no massed fire without time to shift.”

“Air?” Crowe asked, though he knew the answer.

Riley shook his head.

“Fighters are tied up,” he said. “Command says maybe in an hour.”

An hour could be a lifetime.

Or not nearly enough of one.

Crowe stared at the map.

The battalion had pushed out along a country road that now looked less like a path forward and more like a funnel. The tanks, coming from the east, had cut the road behind them. Fields to either side were soft, muddy—bad going for their own vehicles.

Infantry in front.

Steel behind.

And in between, about a hundred and fifty men with rifles, a handful of bazookas, and more determination than anti-armor power.

“Get the bazooka teams up,” Crowe said. “Mine the road. Get everyone into hull-down positions. We’ll make ’em pay for every yard.”

“And Mallory?” Riley asked.

Crowe looked up at the sky.

It was pale blue, scattered with high, thin clouds.

Empty.

“He’ll get here if he can,” Crowe said. “And if he can’t…”

He didn’t finish.

He didn’t need to.

Ten miles back, at a strip of rough earth someone had grandly labeled Advanced Landing Field B-37, Lieutenant Jack Mallory stood next to his Piper L-4 and tried to pretend his hands weren’t trembling.

It wasn’t fear of flying.

He’d gotten past that during his tenth school loop, after he realized his instructor had more ways of making him dizzy than he had ways of protesting.

This was something new.

Fear of what he was about to do.

Of how insane it was.

Of how somehow, in the patchwork logic of war, it also made a crazy kind of sense.

“You don’t have to do this,” the ground crew chief, Sgt. Milo Jenkins, said, as if reading his mind.

“I know,” Jack said.

“Artillery liaison is dangerous enough without turning that crate into a porcupine,” Jenkins added, eyeing the underside of the wings.

The six tubes—pieces of M1A1 rocket launcher, the infantry’s standard anti-armor “bazooka,” modified and mounted—sat in three pairs.

Three under each wing, angled slightly downward.

Each one held a 2.36-inch rocket, the same kind the guys on the ground shouldered at tanks when they got too close.

Usually, a bazooka man got one, maybe two shots off before the tank either spotted him or rolled past.

Jack wanted six chances.

He’d spent sleepless hours with Jenkins figuring out how to clamp the tubes to the wing struts without ripping the fabric.

They used brackets they’d scrounged from a maintenance shed, drilled holes carefully, and wired everything tighter than a drum. The triggers were another story—wires running down into the cockpit, improvised switches taped to the control stick, a tangle of ingenuity and hope.

“Six-Tube Trick,” Jenkins had called it the first time they’d tested it on an old truck carcass in a field.

“The trick is not blowing ourselves up,” Jack had replied.

Now, with the rockets loaded and the word “PULL” stenciled in red next to each toggle, he took a deep breath.

“If I don’t do this,” he said, “who will?”

“Someone with more sense?” Jenkins suggested.

Jack smiled faintly.

“Artillery batteries are busy,” he said. “Fighters are tied up. Tanks are somewhere else. But I can be over that battalion in ten minutes. I can see those Panzers. If I can see them…”

He didn’t finish.

He didn’t have to.

Jenkins shook his head.

“You know they called Carpenter crazy for trying this back in Italy,” he said. “Bolting bazookas to a Cub. Now you’re doing the same thing in France.”

“Yeah,” Jack said softly. “But crazy’s working so far.”

Crazy had knocked out three tanks in the last month—two parked in a farmyard, one caught trying to nose its way out of a grove.

He’d hit them from behind, from the side, always low and fast, launching the rockets and then veering away like his life depended on it.

Because it did.

Those had been one-off targets.

This time, there would be a herd.

“Just remember,” Jenkins said, “that plane is still cloth and wood. Those things look at you funny and you fall apart.”

“I’ll keep it out of their gun sights,” Jack said.

“You better,” Jenkins muttered.

Jack climbed into the cockpit.

The L-4 smelled of oil, canvas, and the faint scent of cigar that no one admitted to. The world narrowed to the cockpit frame, the little instrument panel, the stick in his hand.

He checked his wiring again, tugged each switch.

“Left wing tubes, check,” he said. “Right wing tubes, check. Rockets armed.”

“You get one pass per target,” Jenkins said, leaning in. “Maybe two if you’re feeling lucky. Don’t get greedy.”

Greedy.

As if he were going shopping instead of into a fight.

Jack flipped the magneto switch, primed the engine, and pulled the prop.

The little engine coughed, sputtered, then caught.

The propeller blurred into motion.

The plane vibrated, eager.

Or maybe that was just his nerves.

He waved at Jenkins, taxied to the end of the strip, and turned into the wind.

For a moment, he sat there, engine rumbling, looking down the narrow path of flattened earth.

Somewhere out there, one hundred and fifty men were digging in, listening for the clank of tracks.

He could almost hear it himself.

“Okay,” he muttered. “Let’s talk back.”

He pushed the throttle forward.

The little plane rolled, bounced, then lifted, light as a leaf.

It took exactly seven minutes for Jack to reach the battalion.

He knew the route by heart—over the line of poplars, along the road that curved like a river, past the farmhouse with the red roof someone had painted black to avoid attracting attention.

From above, the battalion’s positions looked like a rough necklace of dark scratches along a hedgerow.

Two hundred yards beyond, the fields dipped, then rose again.

On that rise, like gray-green beetles on a plate, sat the tanks.

There were more than three.

He counted six.

Maybe seven.

They weren’t clustered.

They were spread out, angled, their long barrels pointed toward the hedgerow.

Behind them, half a dozen armored half-tracks and trucks crawled along, infantry riding the decks, rifles bristling.

He felt the old helplessness flicker.

He shoved it down.

Not today.

He did a quick circle, staying high, pretending—for the moment—to be nothing more than an artillery spotter.

Which he was.

He keyed his radio.

“Blackjack Two-Three, Blackjack Two-Three, this is Grasshopper,” he said. “Do you read?”

Static crackled.

Then a voice he knew well—Riley—came through, thin and strained.

“Grasshopper, this is Blackjack Two-Three, we read you,” Riley said. “You’re a sight for sore eyes up there.”

“Wish I looked more dangerous,” Jack said. “What’s your situation?”

“Tanks between us and home,” Riley said. “Artillery’s busy. Air’s busy. We’ve got bazookas and bad nerves.”

Jack’s eyes tracked the tanks.

They were moving forward now, slowly, stops and starts.

Feeling out the ground.

“Copy that,” Jack said. “I see six, maybe seven Panzers. Half-tracks behind. I can call adjustments if the battery frees up. In the meantime…”

He hesitated.

He hadn’t told them.

He hadn’t told anyone down there.

Jenkins had said, “If this works, the stories will tell themselves. If it doesn’t, there won’t be anyone left to complain.”

“In the meantime?” Riley prompted.

“In the meantime,” Jack said, “I’m going to try something stupid.”

There was a long pause.

“Define ‘stupid,’ Grasshopper,” Riley said finally.

“Bazookas,” Jack said. “Six of them. Under my wings.”

Silence.

Then, faintly, over the radio, someone whistled.

“You’re kidding,” Riley said.

“Nope,” Jack said.

“That’s illegal, crazy, or both,” Riley said.

“Probably,” Jack agreed.

Another voice cut in.

“Grasshopper, this is Blackjack Actual,” Crowe said. “Is this a joke?”

“No, sir,” Jack said. “If I can hit their flanks, maybe slow them down. Maybe scare them. Either way, it’s more than I can do just drawing circles on a map.”

Crowe exhaled audibly over the radio.

“You can’t take those things head-on,” he said. “They so much as sneeze in your direction, you’re kindling.”

“I wasn’t planning on a fair fight,” Jack said. “I’ll come in low on the tree line, pop up, fire, and run like hell.”

“You sure about this?” Crowe asked.

“No,” Jack said. “But those guys out there with rifles? They don’t have a lot of options either. I’d like to give them one.”

There was a brief, muffled exchange on the radio.

Probably Crowe and Riley and whoever else was near the handset, arguing.

Finally, Crowe came back.

“All right, Grasshopper,” he said. “I can’t order you to do this. And I can’t officially approve. But I won’t tell you not to.”

“Understood, sir,” Jack said. “Tell your bazooka teams to be ready. If I get their attention, they might miss something closer.”

“Copy that,” Crowe said. “Good luck up there.”

“Luck’s always appreciated,” Jack said.

He banked right, putting the sun behind him as best he could, and dropped to treetop level.

From the hedgerow, the men watched the little plane disappear behind the far stand of trees.

“He’s really gonna do it,” Eddie whispered.

Sam spat into the dirt.

“Better hope those tubes are more than decoration,” he said.

They heard the tanks now, louder—clank, clank, grind, rumble.

“Bazooka teams!” Crowe shouted. “Hold your fire until they’re close! Make your first shot count!”

In foxholes and behind stone walls, men shifted. Bazooka tubes, heavier than they looked, rested on shoulders. Loaders checked rockets, hands shaking.

“Think he can nail one?” Eddie asked.

Sam shrugged.

“Depends on if those tankers are looking up,” he said.

“I would be,” Eddie muttered.

Up ahead, the tanks fanned out, hunting for hull-down positions.

Their commanders, heads out of the hatches, scanned the hedgerow with binoculars, looking for muzzle flashes, movement, anything.

None of them looked up.

They never thought they had to.

Jack flew so low his wheels skimmed the tops of the wheat.

The L-4 wasn’t built for this.

It was built to loiter slowly above front lines, poke its nose over treetops, and direct artillery.

It was gentle.

It forgave sloppy landings.

It was not supposed to hunt tanks.

“Don’t think about that,” he muttered. “Just fly.”

He turned in a wide arc behind the tanks, keeping a stand of trees between them and his approach.

At the last moment, he pulled back on the stick, lifting above the tree line.

The tanks appeared in his windshield like targets on a range.

He could see the top decks, the thin armor on the rear, the open hatches where commanders sat with binoculars.

His world narrowed to one Panzer, slightly separate from the others, its turret angled away.

He flipped the first switch on the left-hand panel.

“Tubes one and two armed,” he said under his breath. “Let’s see if this works twice.”

He lined up the crossbar on the windscreen with the tank’s rear deck, compensated for his speed and the drop he’d seen in tests.

Then he squeezed the improvised trigger.

From the ground, witnesses would later say the little plane spat fire.

To Jack, it felt like someone had kicked the wing.

Two rockets leapt from the tubes, smoke trails stitching a ragged line between air and armor.

For a heartbeat, nothing.

Then a flash.

One rocket hit just behind the turret ring.

The other skipped wide.

The tank jerked, stalled, and a plume of dark smoke belched from the hatch.

The commander, half-out of his cupola, vanished in a burst of movement as his crew scrambled to get clear.

“Hit!” someone screamed over the radio.

Jack didn’t have time to celebrate.

Tracer rounds arced up from the ground, bright beads of light with teeth.

The tank he’d hit wasn’t firing back, but the others were.

Machine guns chattered, bullets stitching the air where he’d been half a second before.

He yanked the stick, banked hard, and dropped back behind the trees, heart pounding.

“Grasshopper, you nailed it!” Riley shouted. “One burning!”

“Tell them not to pop their heads up yet,” Jack said, voice shaking. “I’m coming around again.”

He swallowed, tasted fear and smoke and adrenaline.

“Four left,” he muttered. “Maybe five. Four rockets on the left. Four on the right. Make ’em count.”

Down at the hedgerow, men cheered and swore and peeked over the parapet despite orders to stay down.

“Did you see that?” Eddie shouted. “He hit it! He hit it!”

“Keep your skull down, you idiot!” Sam yelled, yanking him back. “You wanna catch a stray? You cheer when we’re all not getting flattened!”

But even he couldn’t help grinning.

Those tanks, which had looked invincible ten minutes ago, now had a smoking hole in their line.

And the little paper plane was still flying.

“Bazooka teams, stay ready!” Crowe shouted. “They’re rattled, but they’re not blind!”

The tanks shifted.

One turned its turret toward the hedgerow, scanning for the source of the sudden insult.

Another angled its cannon upward, unsure.

They fired a few shells, blind, into the trees beyond.

Branches exploded.

Birds scattered.

The men in the hedgerow ducked instinctively, though the shells weren’t aimed at them—yet.

“Come on, Grasshopper,” Riley whispered into his headset. “Come back around, you crazy son of a gun.”

Jack came in low again, this time from the other side.

He’d learned two things from the first pass.

One, the rockets did what they were supposed to do when they hit.

Two, the tanks would not ignore him now.

He kept his altitude just high enough to clear a haystack and a line of telephone poles.

The second tank in the line was angled slightly toward him, turret turning.

He saw the long barrel swivel, tracking.

“Don’t let him line you up,” he muttered.

He jinked left, then right, feeling the wings flex.

The Grasshopper could dance, but not too wild.

He needed a stable shot.

He picked a tank farther down the line instead—one still turned toward the hedgerow, unaware that death was about to fall from an angle its designers hadn’t planned for.

He armed tubes three and four.

The improvised wiring hummed faintly.

“Don’t fail me now,” he breathed.

He popped up just long enough to clear the last tree, saw the tank’s engine deck, and squeezed.

Two more smoke trails.

One struck the rear hull, where armor was thinner.

The second hit the tracks, showering sparks.

The tank shuddered, veered, and ground to a halt, treads locked.

No flames yet.

But it was out of the fight.

“Another one!” someone shouted over the net. “He’s got two!”

Tracer fire stitched the air again.

A burst ripped through his right wing.

Fabric snapped.

The plane lurched.

Jack’s stomach plummeted.

“Come on, girl, stay with me,” he said, hands gentle but firm on the stick.

He dropped back to the deck, skimming so low he could see the individual blades of grass in his peripheral vision.

The L-4 shook, but the wing held.

Jenkins’ muttered curses about “cloth and wood” echoed in his head.

“Damage?” Crowe asked.

“Nothing important,” Jack lied. “Wing’s ventilated, that’s all.”

“Two tanks disabled,” Riley said. “Half-tracks falling back a bit. You seeing that?”

“Roger,” Jack said. “They’re spooked. Let’s make ’em more spooked.”

He banked again, heart hammering against his ribs like it wanted to jump out and walk home.

He had four rockets left.

Four chances.

Behind the tanks, the infantry riding the half-tracks started to rethink their life choices.

One of them shouted and pointed skyward.

“Flieger!”

The German lieutenant in charge barked orders.

Rifles and machine guns pivoted.

But hitting a small plane buzzing just above the ground, weaving between trees, was like trying to swat a dragonfly with a broom.

A bullet could still find a fuel line, a pilot, a vital wire.

They just had to get lucky once.

Jack had to get lucky six times.

He’d already used up two of those.

“Third pass,” he muttered. “Rule of three. Make it count.”

He changed tactics.

This time, instead of attacking the flank, he came in from behind, where the tank crews felt safest.

From this angle, he could see the rear armor, the exhaust vents, the round shapes of spare track links bolted on.

He picked the third tank in line, slightly separated, its turret still swinging indecisively between hedgerow and horizon.

He armed the remaining two tubes on his left wing.

He popped up.

The tank commander, half-out of his hatch, turned and stared.

Jack saw his face.

Just for a second.

A flash of pale skin, open mouth.

Surprise.

Maybe a hint of “this isn’t in the manual.”

Then Jack squeezed the trigger.

Two rockets streaked out.

One went high, hissing over the tank and disappearing into a field beyond.

The other slammed into the engine housing.

Flame blossomed, orange and black.

Jack yanked the stick.

A burst of tracers flashed past his nose.

Another round punched through the cockpit floor, by his ankle.

He felt the shock more than heard it.

Fuel fumes bit his nose.

“Okay, okay, okay,” he said, half to the plane, half to himself. “We’re fine. We’re fine. We’re fine.”

He leveled out behind a line of trees.

“Three tanks disabled,” Riley said, voice high. “You’re making them nervous, Grasshopper.”

“Nervous is good,” Jack said. “Nervous makes them sloppy.”

He had two rockets left.

On the right wing.

That wing had taken some hits.

He checked the wiring again, eyes flicking between the ground and the panel.

Everything still glowed the way it should.

“Two more,” he whispered. “Just two more.”

On the ground, the effect was immediate.

With three of their lead tanks either burning or immobilized, the remaining armor shifted uneasily.

One tried to back up, but the soft ground sucked at its treads.

Another angled toward a different part of the hedgerow, trying to find a weak spot.

In doing so, it exposed its flank to one of the bazooka teams Crowe had positioned behind an old stone wall.

“Now!” Crowe shouted.

The bazooka man, shaking, squeezed the trigger.

The rocket whooshed out, trailing smoke, and hit the tank’s side with a flat spark.

The tank halted.

A second rocket, from another team, slammed in a heartbeat later.

This one punched through.

Flame licked out.

“Bazooka hit!” Riley yelled. “We got one!”

“Keep at ’em!” Crowe shouted. “They bleed like anything else!”

The enemy armor tried to respond, firing high-explosive rounds into the hedgerow.

Trees blew apart.

Dirt fountained.

Men ducked, ears ringing.

But the line held.

They were no longer sheep in a pen.

They were a pack, hitting back.

And above them, the little paper plane came around again.

By the fourth pass, Jack’s arms ached.

His palms were slick with sweat.

His right foot felt numb, where shrapnel or a bullet had nicked the floor.

“Don’t think about that,” he muttered. “Think about targets.”

The field was chaos now.

Smoke from the burning tanks drifted in gray sheets, obscuring lines.

He used it.

Came in low, ducked into a plume, popped out the other side like a ghost.

The fourth tank in line, distracted by the bazooka casualty nearby, hadn’t fully turned its turret.

He could see its rear quarter.

He armed the last two tubes.

The right wing shuddered as he did.

“Come on,” he whispered. “Just hold together a little longer.”

He lined up.

Squeezed.

The last two rockets shot out.

One struck dead center on the rear deck.

The armor there wasn’t meant to take that kind of focused hit.

Something ruptured.

A dark cloud belched.

The tank ground to a halt.

The second rocket missed, hitting the dirt and exploding in a shower of earth.

“Tubes empty,” Jack said aloud, as if the plane needed to be told. “That’s it. Show’s over.”

He banked, heading back toward friendly lines.

Bullets still stitched the air.

But less of them now.

Some of the enemy gunners had stopped shooting.

They were too busy trying not to be in the next tank that caught fire.

“Grasshopper, this is Blackjack,” Crowe said. “You’re clear. You did it.”

“Not alone,” Jack said.

He glanced down.

The enemy formation was in shambles.

Four tanks were clearly out of action—two burning, two stalled.

A fifth had an ugly black mark on its side from the bazookas and wasn’t moving.

The sixth—maybe seventh, he’d lost count—was backing away, slowly, treads churning.

The half-tracks, under sporadic small-arms fire from the hedgerow, were reversing too, commanders gesturing frantically.

They were retreating.

Not regrouping.

Retreating.

He let himself breathe.

Just once.

Back at the hedgerow, men laughed and shouted and thumped each other on the helmet.

“We did it!” Eddie yelled. “They’re pulling back!”

“Don’t jinx it,” Sam said, but he was grinning.

Crowe stood, dust and leaf bits clinging to his uniform, and watched through his binoculars as the enemy armor withdrew.

Not in good order.

In messy chunks.

Artillery, now freed from its earlier task, started dropping shells on the road behind them, adding urgency to the retreat.

“Riley,” Crowe said, “get me division. I want to tell them how a paper plane did the job of a tank battalion.”

“Yes, sir,” Riley said, grinning as he adjusted the radio.

Jack landed shakily back at B-37.

The ground rushed up faster than he liked.

He bounced once, twice, then settled, the plane wobbling as it rolled to a stop.

His hands wouldn’t unclench from the stick for a second.

He flexed them, feeling the tremor.

His right foot tingled sharply, pain catching up now that adrenaline was ebbing.

He looked down.

The floor around his boot was stained dark.

“Great,” he muttered. “Didn’t even feel that.”

Jenkins ran out, waving.

“What did you do to my airplane?” he shouted as Jack cut the engine.

“Gave it some stories to tell,” Jack said weakly.

He opened the door and tried to climb out.

His leg buckled.

Jenkins caught him under the arm.

“Easy there, hero,” Jenkins said. “Don’t faceplant. It ruins the dramatic entrance.”

Jack laughed, then winced as his foot screamed protest.

“It’s nothing,” he said. “Just a scratch.”

“Yeah, and I’m a ballerina,” Jenkins replied. “Sit.”

He half-carried, half-dragged Jack to a crate, propped him up, and then turned to the plane.

The right wing looked like someone had taken a hole punch to it.

Several of the tubes were empty, scorched at the mouth.

“What’d you hit?” Jenkins asked, awe creeping into his voice.

“Four,” Jack said. “Maybe five. Bazooka teams got one, too. They’re pulling back.”

Jenkins let out a low whistle.

“Four?” he said. “In that?”

He slapped the side of the L-4 affectionately.

“Guess we gotta start calling her something fancier than ‘paper plane,’” he said.

“Don’t get too cocky,” Jack said. “She’s still cloth.”

“Cloth with teeth,” Jenkins said.

He looked at Jack.

“You realize command is never gonna believe this,” he said. “Not until they see the photos. And even then, they’ll say it was luck.”

Jack shrugged.

“Luck’s part of the job,” he said. “So is being too stubborn to know when to quit.”

Jenkins snorted.

“Speaking of quitting,” he said, “medics are on their way. Don’t argue with them. They’ve got needles.”

Jack groaned.

“I hate needles,” he said.

“And tanks, apparently,” Jenkins said.

Jack smiled faintly.

“Tanks started it,” he said.

News of the “six-tube trick” traveled faster than official reports.

By the time division HQ got the battalion’s message, someone’s cousin in another unit was already telling the story to a cook two towns over.

They say this skinny pilot strapped bazookas to his lawnmower with wings and dove at the tanks like a madman. Took out six. No, I swear. Six. Saved the whole outfit…

Officially, the after-action report was more restrained.

“Enemy armored counterattack disrupted by low-level air harassment and infantry anti-armor fire. Four enemy tanks destroyed, two disabled, remaining elements withdrew in disorder. Friendly casualties minimal.”

Unofficially, the men who’d been lying in the mud that afternoon had their own way of putting it.

“We were about to get rolled,” Sam said later, sitting in a field kitchen, hands wrapped around a mug of bitter coffee. “Then Mallory and his flying porcupine showed up and poked holes in their pride. We owe him a drink. Or ten.”

Eddie, still riding the high of not being crushed into the French countryside, nodded vigorously.

“I never thought I’d cheer at something that looked like it belonged at a county fair,” he said. “But when those rockets hit—man. I’ll never call it a paper plane again.”

“You will,” Sam said. “Just with more respect.”

Captain Crowe, when asked by a brigade staff officer if he had any comments, had put it simpler.

“Sir,” he said, “I watched an unarmored liaison aircraft with a top speed slower than my jeep knock out as many tanks as a company of Shermans on a good day. I don’t know what you call that, but where I come from, we call it guts.”

A week later, Jack sat in a medical tent, his foot bandaged, his L-4 undergoing more patch-ups than a kid’s bicycle.

The doc had insisted he stay off it for a bit.

“Just a graze,” Jack had protested.

“A graze that went through your boot and left shrapnel in your ankle,” the doc had replied. “You wanna be walking on that in ten years? Sit.”

So he sat.

He read dog-eared magazines. He wrote letters to his sister back home. He listened to the quiet talk of other wounded men, some of whom would go back to the line, some of whom wouldn’t.

One afternoon, the tent flap rustled.

Crowe ducked in, Riley behind him.

“Well, if it isn’t the hero of hedgerow four,” Crowe said.

Jack flushed.

“Sir,” he said. “I just did my job.”

“You did more than that,” Crowe replied.

Riley grinned.

“You know they’re writing about you up and down the corps now?” he said. “Some colonel called your stunt ‘innovative use of existing anti-armor assets.’”

“That’s one way of putting it,” Jack said.

Crowe handed him a folded paper.

“Here,” he said. “From division.”

Jack unfolded it.

It was a commendation, official language and all.

For “extraordinary initiative and courage in the face of enemy armor,” for “disabling multiple enemy tanks with improvised rocket armament on a liaison aircraft,” for “saving the lives of approximately one hundred and fifty soldiers in imminent danger of encirclement.”

Jack stared at the number.

One hundred and fifty.

It was different seeing it in print.

Not just faces in foxholes.

Not just voices on the radio.

“There were that many?” he asked quietly.

Crowe nodded.

“If those tanks had broken through…” he said. “Well. We’d be mailing a lot more letters home.”

Jack swallowed.

“I just didn’t want to hear that clanking and feel helpless again,” he said.

Crowe studied him.

“You know,” he said, “most people in your position would’ve said, ‘Not my job’ and circled overhead calling in artillery that wasn’t there. You turned your little kite into a tank buster.”

Jenkins, who’d slipped in behind Riley, snorted.

“Don’t encourage him, sir,” he said. “Next thing you know he’ll be asking me how many rocket tubes we can fit under those wings before she stops flying.”

“More than six?” Jack asked, half-joking.

“Absolutely not,” Jenkins said. “Six was already pushing my sanity.”

They laughed.

For a moment, in that tent, the war felt far away.

Just men, joking, shaking their heads at the crazy things they did to survive.

Then Riley’s radio crackled from outside.

“Grasshopper, this is Blackjack Two-Three,” the faint voice said. “We’re moving again. Hope your crate’s ready for round two when that leg heals.”

Jack smiled.

“Tell them,” he said to Riley, “that the six-tube trick’s retired. Next time we’ll think of something even dumber.”

“You’re gonna give me gray hair,” Jenkins muttered.

“You already have gray hair,” Riley said.

“That’s from him,” Jenkins snapped, jabbing a thumb at Jack.

Crowe just shook his head, amused.

“Rest up, Mallory,” he said. “There’ll be more days like that one. Maybe not with tanks. Maybe with something else. But I’ve got a feeling your knack for ‘crazy that works’ isn’t done yet.”

“Yes, sir,” Jack said.

When they left, he lay back on the cot and stared at the canvas above.

He could still hear the tanks.

But now, over that clank and grind, he could hear something else.

The whoosh of rockets.

The cheer in Riley’s voice.

The roar of a little engine that, for ten minutes on a fall afternoon, had sounded louder than any Panzer.

He didn’t think of himself as a hero.

Heroes were other men.

Men who’d done more.

Sacrificed more.

He thought of himself as something simpler.

A pilot who’d seen a problem and refused to accept he had no tools to solve it.

Even if those tools were just six tubes, some wire, and a willingness to fly a paper plane straight at steel.

Years later, long after the war, a kid at an airshow tugged at Jack’s sleeve.

He was older now, hair grayer, lines at the corners of his eyes deeper.

He’d been invited to talk about “improvised air-ground tactics” to an audience that mostly wanted to see the stunt pilots.

The kid, maybe ten, pointed at the old Piper Cub on display.

“Did you really put rockets on one of those?” he asked, eyes wide.

Jack smiled.

“I did,” he said.

“Aren’t tanks, like, super strong?” the kid asked. “How could this little thing hurt them?”

Jack looked at the plane.

At its fabric skin, stretched over wooden ribs.

At its small wheels.

At its single propeller.

“It didn’t hurt them by being big,” he said. “It hurt them by being where they didn’t expect it. By using what it had, not wishing it was something else.”

The kid frowned, thinking.

“So… it was like a paper plane with teeth?” he asked.

Jack chuckled.

“Something like that,” he said.

“When I make paper planes,” the kid said, “my teacher says they can’t do anything. They just fall.”

Jack looked at him.

“Sometimes,” he said, “the things people think can’t do much surprise them the most.”

He wasn’t talking about planes anymore.

He was thinking of the men in foxholes who’d stood their ground against tanks.

Of the ground crew who’d helped him bolt on those tubes.

Of a young radio operator’s steady voice over static.

Of the mechanics and cooks and clerks and all the other “paper airplanes” in the machinery of war who’d found ways to bite back.

The kid nodded solemnly, as if committing the lesson to memory.

“Can you show me how to fold one that flies better?” he asked.

Jack grinned.

“That,” he said, “I can definitely do.”

As they bent over a sheet of paper, the roar of modern jets overhead shook the sky.

He barely heard it.

In his mind, he was back in that little cockpit, low over the French fields, six tubes under his wings, heart pounding, stubborn as the day was long.

A sound echoed—distant, remembered.

Not the clank of tanks.

Not the whoosh of rockets.

The sound of one hundred and fifty men cheering from a hedgerow, knowing they would see another sunrise because a “paper plane” had decided not to stay harmless.

THE END

News

When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six Hours Later, His Lone Gamble Turned Their Mockery into Shock, Freedom, and a Furious Argument in the War Room

When the One-Eyed Canadian Scout Limped Toward a Fortress Holding 50,000 of His Countrymen, His Own Brothers in Arms Laughed—Six…

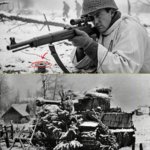

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare Rifles, Ignored His Own Commissar’s Orders, and Turned One Hill Into a “Forest of Ghosts” That Killed 225 Attackers and Broke the Siege

His Battalion Was Surrounded and Out of Ammunition When the Germans Closed In—So a Quiet Soviet Sniper Stole Six Spare…

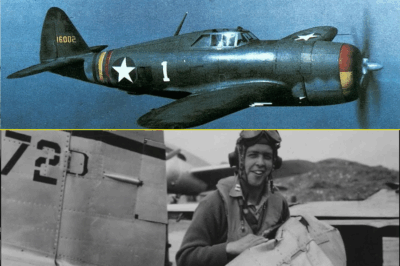

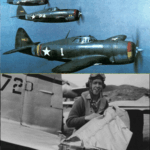

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That Weight Into a Weapon and Sent 3,752 Luftwaffe Fighters Plummeting From the Sky

Designers Mocked the P-47 Thunderbolt as a Bloated ‘Flying Tank’ That Would Never Dogfight — Then Its Pilots Turned That…

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion, Claimed Ninety-Six Enemy Combatants Without a Single Direct Shot, and Sparked One of the War’s Most Tense Command Arguments

When a Quiet American Sniper Strung a Single Telephone Line Across No-Man’s-Land, His Ingenious Trap Confused an Entire German Battalion,…

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to Notice — But What He Saw, What He Asked, and the Argument That Followed Changed the Boy’s Entire Life Forever

When the Diner’s Owners Quietly Slipped a Stray Kid Free Meals Every Day, They Never Expected a Visiting Millionaire to…

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet Single Dad Janitor Stood Up, Walked to the Defense Table, and Changed Everything

When the Millionaire’s Fancy Attorney Panicked and Ran Out of the Courtroom, Everyone Expected a Mistrial — Until the Quiet…

End of content

No more pages to load