Tokyo’s Secret 1942 Debate: Japan’s Bold Move Toward Australia Collapsed When Intelligence Reported Australian Factories Had Equipped Eight Divisions and Turned the Continent Into a Trap

The telegram arrived in Tokyo the way bad news often does—quietly, folded into official language so it wouldn’t sound like fear.

It didn’t come with drama. No shouting courier, no slamming doors. Just a thin paper file handed from one uniformed clerk to another, then carried down a corridor where polished floors reflected ceiling lights like calm water.

The cover sheet read: SOUTHERN STRATEGY—AUSTRALIA.

Inside, the words were sharper.

Not about ships or weather, not about the usual estimates of distance and supply. This was about something Japan could not simply outfight with courage or surprise.

It was about factories.

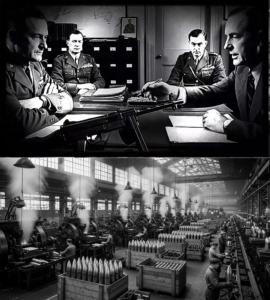

Captain Sadatoshi Tomioka—head of planning on the Navy side, a man who loved maps the way some men love poetry—held the file in both hands as if it might bite. His eyes moved quickly, absorbing the summary: Australia’s war economy was expanding at a pace that didn’t fit the old image of a distant, sleepy outpost. Japan had maintained diplomatic representation in Australia until late 1941, and the implication hung in the report like a warning: Tokyo had not been blind. The Strategist

Yet the scale, written plainly, was still a shock.

A junior officer watched Tomioka’s face, waiting for permission to breathe.

Tomioka didn’t look up. “Read it again,” he murmured.

The officer read, voice careful:

“By March 1942, Australia had produced enough armaments to fully equip six infantry divisions.”

A pause.

“By June 1942, Australian production had equipped eight infantry divisions with modern weapons.” The Strategist

Eight.

Not one or two formations with borrowed gear. Eight divisions able to stand on their own feet—armed, supplied, and increasingly confident.

Tomioka’s mouth tightened. For weeks he’d argued in conference rooms that a limited landing in the north could be done with a “token force,” that Australia was too empty and too far apart to resist quickly, that the real danger was allowing the United States to use Australia as a springboard. Wikipedia

Now, the paper in his hands suggested the opposite: the continent was becoming a trap—wide enough to swallow an invader, and armed enough to bite back.

He turned toward the wall map—New Guinea, the Coral Sea, the long reach toward the Australian coastline.

There are moments when a strategist realizes the world has quietly changed while he was still arguing with the old version of it.

This was one of those moments.

Two days later, the Imperial General Headquarters met in a room where words carried more weight than weapons.

On the Army side, men sat with faces carved from discipline. They had been warning for months that Australia was not a neat target. Its size alone was a problem; its distance, a second; its potential for Allied reinforcement, a third.

Prime Minister Hideki Tojo had opposed an invasion as unfeasible, and later insisted Japan lacked the troop strength and the supply capacity for “actual physical invasion.” Wikipedia

But the Navy had kept pushing, because the Navy did not fear distance the way the Army did. The sea was the Navy’s home. If anything, distance felt like an advantage.

Tomioka stood when permitted and placed the intelligence summary on the table. The paper looked small compared to the stern faces surrounding it.

“Before we discuss numbers,” he said, “we must discuss reality.”

An Army general—older, heavier, unimpressed—gestured sharply. “Reality is that Australia is vast.”

“Correct,” Tomioka said. “And the vastness is becoming… populated by armaments.”

The phrase landed oddly in the room. Not poetic. Almost ugly.

An Army planner spoke, voice like a file scraping metal. “Our estimate remains: a minimum of ten divisions, perhaps more, to invade and hold.” Wikipedia

Tomioka countered automatically, as if habit still had authority. “The Navy’s estimate for a northern landing is smaller—three divisions could secure key coastal enclaves.”

The Army side didn’t laugh.

They didn’t need to.

One of them slid a ledger forward. “Transport alone would require 1.5 to 2 million tons of shipping,” he said, tapping the figure once, as if a single tap could end the debate. Wikipedia

Shipping was not an abstract number. It was the difference between feeding conquests and starving them. It was the difference between holding islands and losing them. It was the difference between victory and overreach.

Tomioka’s eyes flicked to the intelligence summary again.

Australia’s factories. Eight divisions.

He felt a strange irritation—not at the Australians, but at time itself. Time was doing what enemy fleets could not: building Australia into something harder.

“And,” the Army planner continued, “Australia will not sit still while we unload.”

He said it as if the very thought was insulting: that an enemy would dare to prepare.

Another officer added the line Tojo had favored for months: instead of conquering the continent, Japan could attempt to isolate it—cut communication lines, deny it reinforcement, and apply pressure until it bent. Wikipedia

Tomioka knew that argument. He hated it because it lacked the clean certainty of a landing arrow on a map. Isolation sounded like waiting. Waiting sounded like surrendering initiative.

But now he held proof that initiative could be punished.

Eight divisions did not mean Australia was unbeatable. It meant Australia would not be easy.

And “not easy” was sometimes enough to change a war.

Far away from Tokyo’s polished tables, the engine of that change was loud, oily, and ordinary.

In Melbourne, in Footscray, in workshops that smelled like hot metal and machine grease, women and men moved in steady rhythm. They weren’t thinking about Japanese staff debates. They weren’t imagining arrows on maps.

They were thinking about quotas.

A foreman in a munitions factory shouted over the noise, pointing at rows of shell casings like a man pointing at a harvest. Women in work clothes and rolled sleeves handled metal with practiced care, spinning and finishing artillery shells in a process that demanded speed without error.

In Sydney, ammunition workers packed cartridges until their hands felt like machines themselves—count, pour, seal, stack—again and again, day after day, because repetition was its own kind of defense.

In Adelaide, women posed for a group photo outside a factory making Beaufort components—smiling the way people smile when they’re tired but proud to be useful.

None of it looked like heroism in a newsreel. It looked like labor.

And yet, back in Tokyo, those workshop rhythms were being translated into military arithmetic.

Australia’s “great strategic victory,” one modern assessment argues, wasn’t a single battle at sea—it was the expansion of science, technology, and industry that helped convince Japan an invasion was too dangerous. The Strategist

A continent was turning itself into a fortress not by building a wall, but by building capacity.

In the headquarters meeting, Tomioka tried one more time.

“If we do not seize Australia,” he said, “the Americans will use it as a base. They will bring their airfields, their supplies, their momentum—”

An Army general cut him off with a calm that felt like contempt. “Then do not give them the opportunity. Expand the perimeter. Take the islands that matter. Isolate the base.” Wikipedia

Another Navy voice—one Tomioka didn’t like hearing—added that even within the Navy, the idea wasn’t universal. Admiral Yamamoto had consistently opposed the invasion proposal. Wikipedia

It was happening: Tomioka could feel the debate slipping away from him.

He reached for the only weapon that sometimes worked in a room of hardened planners—fear.

“Eight divisions,” he said, tapping the intelligence summary. “If they are already equipped by June, what will they look like by the end of the year? And what will America add to that?”

No one answered immediately.

Because the fear was real.

But the Army did not respond to fear by leaping. It responded to fear by refusing risk.

One planner read aloud the blunt conclusion from the Japanese side’s own internal records about the “token force” idea—dismissed as nonsense, labeled “gibberish.” Wikipedia

The word hung there, embarrassing and final.

Tomioka felt heat rise in his neck.

He wasn’t a fool. He understood shipping. He understood distance. But he also understood something the Army often underestimated: momentum. A war could be won in windows—short periods where bold moves created irreversible facts.

He believed early 1942 was such a window.

But Australia’s factories were closing it.

And then another blow landed—not from Australia, but from the ocean.

The room turned its attention to operations already in motion—efforts designed to isolate Australia from the United States by advancing through the South Pacific. Wikipedia

A strategy that sounded less glorious than invasion—but far more achievable.

The decision, when it came, was not announced like a verdict. It was simply… accepted.

The invasion proposal was rejected, and Japan’s focus shifted toward isolation—an offensive that would soon be disrupted by major naval battles in mid-1942. Wikipedia+1

Tomioka sat down slowly, as if the chair had become heavier.

Around him, men began talking about next steps, new priorities, other islands.

But Tomioka could still hear the number in his head:

Eight divisions.

A factory-built warning.

In Australia, nobody knew the full story in Tokyo. They didn’t need to.

They had their own story—one written in sirens, blackout curtains, and headlines that shouted about danger. The fear of invasion was widespread, and it pushed Australia to expand its military and its war economy while tightening links with the United States. Wikipedia

In small homes and big cities, people argued about where the threat would come from and when. They traced invisible lines on kitchen tables, pointing north, pointing east, imagining ships on the horizon.

But in the War Cabinet documents—monthly reports, production tallies, allocation lists—another story was being written with quiet stubbornness: a nation that intended to be expensive to attack. The Strategist

The workers didn’t call it strategy. They called it work.

A woman in Footscray, hands stained with oil, didn’t know what “twelve divisions” meant in a Japanese appreciation. She didn’t know what “1.5 million tons of shipping” looked like on a planner’s page.

She only knew that if she did her job right, somebody’s gun would fire when it needed to. Somebody’s unit would have what it lacked last month. Somebody would stop feeling like they were waiting to be hit.

And slowly—almost invisibly—those small certainties added up into something a distant enemy could measure.

Back in Tokyo, Tomioka walked alone after the meeting, down a corridor where everyone pretended not to look at him.

In his mind, the argument replayed in sharper detail than it had actually occurred.

He told himself he wasn’t wrong—only early.

He told himself the Army lacked vision.

He told himself he’d find another way to protect Japan’s perimeter.

But the truth that kept returning was simpler, and therefore harder:

Japan had met a kind of resistance it did not know how to bomb or blockade quickly.

Industrial momentum.

An enemy that could make weapons faster than fear could break it.

And this mattered because the Navy’s dreams were always constrained by one brutal fact: a ship could sail only as far as supply allowed. An island could be taken only as long as it could be fed. A perimeter could be stretched only until it snapped.

Australia—huge, distant, armed by its own factories—was a continent-sized test of that snapping point.

Even Allied assessments later would conclude that a Japanese invasion was enormously demanding and unlikely, with reasons including the scale of commitment required and other strategic risks. Anzac Portal

Tomioka didn’t need Allied conclusions. He’d seen the same logic on his own table.

The war was not ending. But one path through it had just closed.

The most dangerous part of a rejected plan is what it leaves behind.

Not the troops that never landed, not the ships that never sailed.

But the lingering idea—inside enemy minds and friendly minds—that it might have been possible if the timing had been different.

That idea can fuel myths for decades.

In Australia, many people long believed an invasion was imminent. In later years, historians and educators have debated how real the threat truly was, noting that while invasion fears were intense, invasion plans were not adopted as actual operations. Wikipedia+1

So here is the version that matters most—the one hidden inside that Tokyo debate:

Japan’s Navy did propose an invasion. Japan’s Army opposed it as impractical. Tojo rejected it as unfeasible. Wikipedia

And among the reasons—alongside geography, shipping limits, and competing priorities—was a realization that Australia was not a soft target waiting for history to happen to it.

Australia was building.

Six divisions equipped by March, eight by June, according to one detailed argument grounded in contemporary production reporting. The Strategist

Numbers on a page.

But also: women finishing shells in Footscray.

Workers packing ammunition by the thousands.

Factory teams turning aircraft components into something that could fly and fight.

A continent becoming harder, week by week.

And when Tokyo finally saw that clearly—when it understood that “Australia” didn’t just mean coastline and distance but also workshops, supply chains, and divisions that could be armed without asking anyone’s permission—the invasion argument lost its clean shine.

It became what it truly was:

A gamble with terrible odds.

Tomioka, walking alone down the corridor, understood something he did not want to admit even to himself:

Sometimes the battle that changes everything is not fought at sea.

Sometimes it happens in a factory—quietly, relentlessly—until the enemy realizes the door is no longer worth kicking in.

THE END

News

An Apache Man Was Left Tied to the Mesquite — Until a Rancher’s Daughter Stood Her Ground Against a Charging Bear and Changed Two Worlds

An Apache Man Was Left Tied to the Mesquite — Until a Rancher’s Daughter Stood Her Ground Against a Charging…

“That’s Forbidden,” She Whispered—And the Rancher Understood Why a Single Word Could Splinter a Quiet Town Overnight

“That’s Forbidden,” She Whispered—And the Rancher Understood Why a Single Word Could Splinter a Quiet Town Overnight The first time…

“Do It Now—Before the Wind Changes”: One Rancher’s Midnight Choice, a Coil of New Wire, and the Decision That Ended the Open Range Forever

“Do It Now—Before the Wind Changes”: One Rancher’s Midnight Choice, a Coil of New Wire, and the Decision That Ended…

“Best Food I’ve Ever Had,” She Whispered—The Day German Women POWs Tasted American Cooking and Realized the War Had a Stranger Ending

“Best Food I’ve Ever Had,” She Whispered—The Day German Women POWs Tasted American Cooking and Realized the War Had a…

On D-Day’s Darkest Morning, “Exploding Dolls” Fell From the Sky and a Phantom Army Fooled 8,000 Germans Into Waiting While Omaha Burned in Silence

On D-Day’s Darkest Morning, “Exploding Dolls” Fell From the Sky and a Phantom Army Fooled 8,000 Germans Into Waiting While…

Shock in a Quiet Barracks: A Wehrmacht General Demanded Answers, and What He Saw in the American Women’s POW Ward Rewrote His Beliefs Overnight

Shock in a Quiet Barracks: A Wehrmacht General Demanded Answers, and What He Saw in the American Women’s POW Ward…

End of content

No more pages to load