“‘They’re Giants!’ the Rumors Said — In a Bavarian Village Where No One Had Ever Seen an American, The Day the Columns Rolled In Was Supposed to Bring Fear, But What Happened When We Finally Looked Up at Them Changed Our Idea of Enemies, Strength, and Home.”

The first time we heard the engines, the windows rattled like teeth in winter. Mothers pulled curtains shut as if cloth could keep out history. The men who were left — old, tired, or returned from hospitals with crutches — stood in doorways and stared at the road where it curved past the mill.

“They are taller than we imagined,” my uncle whispered, as though height were a weapon.

For months we had eaten rumors: Americans who towered over doorframes, who had pockets full of chocolate, who smiled with perfect white teeth, who would shoot first and ask questions later, who would put a radio in every kitchen, who would tear down the church tower to build a cinema. The rumors contradicted each other, which meant they had the ring of truth.

I was thirteen and small and hungry for something that wasn’t fear. When the first olive-drab truck rounded the bend, our village — Hirschenfeld, a place of steep roofs and a river that remembered spring — forgot to breathe.

The truck stopped where the road widened. Dust drifted over it like a veil. The soldiers’ helmets were dappled the color of wet stones. One of them jumped down, tall enough to make the rumor smile with satisfaction.

“Guten Morgen,” he said, carefully, as if each letter had a splinter.

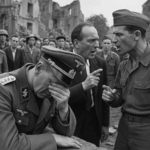

Our mayor, who had never been brave, smoothed his jacket and stepped forward with the handkerchief we had chosen as a white flag. The handkerchief had once been embroidered with his wife’s initials; she had unpicked them in the night. He held it up like a truce offered to the sky.

The tall soldier nodded. Another man climbed down after him with a notebook and a pen tucked behind his ear. He wore his height like an unbuttoned coat, something he couldn’t help and didn’t think about. He looked over our roofs, our faces, and the portraits of missing sons in our windows. Then he looked at the river and smiled.

“Bridge?” he said, half question, half memory.

“It was blown in March,” the mayor said in German, then added in the International Language of Desperation, “Kaputt.”

The tall soldier said something to the one with the notebook. The notebook man nodded, took the pen from behind his ear, and stepped closer.

“I am Lieutenant Segal,” he said in good German, the kind learned from a teacher who had loved the subjunctive and cafés. “We are here to occupy until order is established. We will need billets. And bread, if there is bread.”

“Bread?” my uncle repeated, as if the word were a magic trick. “Für uns?”

“For everyone,” the lieutenant said.

The tall one pointed at me and then at the measure marks on the bakery doorframe where Father used to measure me each birthday and write the date. He grinned and held his hand flat above my head, comparing me to the chalk lines. I was rooted to the spot and suddenly aware of my scuffed shoes. The tall soldier reached into a pocket and pulled out a paper-wrapped rectangle.

“Schokolade,” he said.

The paper was thin, the color of promises. I looked at Mother. She gave the smallest nod, a movement like a bird landing. I took the rectangle and felt it soften in my warm hand. Chocolate. Real chocolate. The last time I’d tasted it, the war was still a rumor.

“Danke,” I said, surprised at how easy gratitude sounded in my mouth.

The tall soldier’s name turned out to be Collins. He introduced himself later with a hand over his heart and a bow that was almost theatrical. “Joe,” he said, then pointed to the lieutenant. “Abe.” He pointed to the driver, a sunburned man with quick eyes. “Penn.” He went down the row of men, saying names that sounded like postcards: Ramirez, O’Malley, Whitaker, King. We had known only one kind of name for so long that the list felt like opening shutters.

They were indeed tall — taller than our timbers seemed to expect when they leaned into doorways — but they were also young, and their faces moved when they spoke, not locked in the careful masks we had learned. They looked at our goat, our stone well, our stack of chopped wood, the little patch of turnips with a kind curiosity, as if cataloging the things that people did to make a life.

The lieutenant asked for the priest, then the schoolteacher. The priest came at once, dust on his cassock, the peace flag from last week still tied to his bicycle. The schoolteacher took longer; she had been walking the river looking for wild garlic to stretch the soup. They spoke in good German and careful English and drew little diagrams on the notebook with a pencil that had teeth marks.

“We will not take your church,” the lieutenant said, anticipating our fear before we voiced it. “We will not take your children. We will not take your dignity. But we will take your guns.” He let the last word rest like a stone on a table.

“We have none,” the mayor lied.

“Then it will be easy,” the lieutenant said.

By noon, the square looked like a postcard from a world that liked order: trucks parked in neat rows, soldiers moving like the music of drills, villagers watching with arms folded. The baker’s wife, who had not smiled since the telegram, found a small private smile when Penn asked for “Brot, bitte?” with the solemnity of a church prayer and paid with a ration coupon and a tin of peaches.

Peaches. The word rolled through us and made everything seem brighter.

That afternoon, a group of children, including me, watched as Collins tried to explain baseball to the boys using a broom handle and a potato. “You hit, you run,” he said, miming both. “He throws, you catch.” He tossed the potato gently to little Franzl, who swung with all the concentration of a scientist and connected with a splat that sent peeled potato like confetti. The Americans laughed with their whole torsos; the mothers flinched; the boys looked at each other as if a secret door had opened into a room where laughter was allowed.

“Tomorrow,” Collins said, wiping potato from his cheeks, “I bring a ball.”

“Wir haben einen Ball,” Franzl said, and vanished toward his house, only to return with something that had once been a ball and was now a thesis on persistence. They played until the shadows stretched across the road, and the ball, whatever it was, discovered the laws of physics anew in American hands.

That night, the Americans slept in our spare rooms, on floors, in barns — wherever the lieutenant’s notebook assigned them. Collins slept in our guest room, on Father’s old straw mattress, his long feet comically near the rail. In the kitchen he tried to help with the washing up and learned the German word for “careful” when he nearly tipped the basin.

He watched Mother slice bread with the reverence of someone watching a ceremony. He pointed at our doorframe and its chalk marks, and then, holding his palm flat, he touched the highest one.

“Vater,” I said. “He was tall.”

“Fighting?” he asked, the English word thick with German history.

“Lost,” I said, and watched the word and its meanings land in his eyes.

“I am sorry,” he said, not as a phrase one carries like a coin but as a thing carved inside.

In the morning, the lieutenant gathered everyone under the linden tree in the square. The church bells rang because the bells had rung every morning as long as anyone remembered, through joy and funerals and years when the only news was rationing and lists. He stood on a crate that had once held nails and now held a man who was attempting to nail us all to a different future.

“We will establish a checkpoint at the mill,” he said. “Curfew at nine. No flags for a while. No marches. No more speeches from the balcony.” He looked up at our Rathaus, its balcony a mouth that had eaten too much sound. “There will be food distribution when the convoy arrives. We will pay for what we requisition. You will bring any weapons to the church by noon tomorrow. If not, we will search and we will be angry.”

The last sentence carried a smile that wasn’t funny.

Then he did something we had not seen anyone in a uniform do in years. He put the notebook away and asked a question.

“What do you need?” he said.

Silence, the kind that hums.

“Salt,” the baker’s wife said, surprising herself with the courage to name a specific.

“Shoes,” said an old man, lifting his foot to show the careful weave of rope that had replaced leather.

“Medicine,” said the schoolteacher, touching a pocket where there had once been aspirin.

“Roof tiles,” said the priest, because even rain behaves like an enemy when wood goes bare.

“Grammar books,” I said, and my classmates stared as if I had confessed a crime. “For English.”

“English?” Collins repeated, laughing. “For what?”

“For you,” I said, and nobody laughed.

The lieutenant wrote every request down as if each were a vow.

That afternoon, I watched Collins at the mill, where he stood with Penn and two others, looking at the stump where the bridge had been. The river was low but quick, as if it were hurrying to get somewhere better. Collins picked up a stick and began to draw in the dust: beams, planks, triangles where triangles make everything hold when gravity wants to argue.

“Pontoon,” Penn said.

“Borrow the boats,” Collins said, pointing at the fishermen’s upturned hulls that had not tasted water since the winter freeze. “Rope here. Rope there. Planks. One truck at a time.”

“Engineers?” Penn asked.

“We are engineers,” Collins said, and winked at the fisherman who had sidled closer, pretending to be interested in dust.

By evening, they had a plan that looked like all good plans: impossible until it wasn’t. The fishermen looked at the Americans with begrudging respect, which is the most durable kind. The miller’s daughter brought a jug of cider, and for the first time in months we pretended that planning might be fun.

At sundown, the Americans did a thing that was both strange and familiar. They stood in a rough circle, took off their helmets, and bowed their heads. No one spoke, and all the words not spoken felt like a prayer.

Mother and I stood at our window and watched.

“Do they pray like us?” I asked.

Mother, who had prayed for sons, bread, and the gentle end of a fever that had come in spring and stayed until winter, said, “Everyone prays the same when they do it right.”

We slept with the Americans in our house that night. When the clock struck two, I woke to the sound of a man breathing unevenly. I went to the hall and saw Collins sitting at the top of the stairs in a square of moonlight, his hands gripping his knees.

“Alptraum?” I said, surprising both of us with my boldness. “Nightmare.”

He laughed softly, as if the word itself had soothed something. He nodded. “Boom,” he said, and mimed a plane diving with his hand. “Boom.” He opened his hand like a flower. “Then quiet.” He tapped his ear, shook his head. “For a long time.”

He looked at me, and although he was taller than every rumor, in that moment he was my height exactly.

“Water?” I asked.

He nodded. In the kitchen, he tried to help and knocked the ladle. It clanged, and we froze like thieves, then rolled our eyes in unison at our own fear.

“Danke,” he said when I handed him the cup. “You English good.”

I smiled. “Not good. Better soon.”

He bowed, a gesture that looked old-fashioned on a man with American boots.

The next day, the convoy arrived: trucks bearing sacks of flour, crates of canned goods, boxes labeled with acronyms we learned to translate into hope. Children ran behind the vehicles like parade confetti. The Americans handed out tins with labels that sounded like fairy tales — peaches, pears, ham — and they did it with a formality that made each gift feel like a contract.

At noon, the church filled with the sound of metal placed on wood as old pistols, hunting rifles, and a few ugly machines that had lived under floorboards for too long were surrendered. The priest stood beside the altar and nodded to each person as if they were confessing and being absolved. The lieutenant’s notebook lay open on the lectern, a blank line at the bottom of each page as if to say, “We are not finished.”

Not everyone came. The Americans knew that. They did not turn into wolves; they turned into neighbors with very good boots and a clear sense of where doors were. They knocked. Sometimes they waited. Sometimes they came back with a carpenter to fix a hinge that had squeaked since the year without a summer.

At the river, the bridge grew as if it had been planted. We watched men in uniform tie knots with hands that had also written letters and learned to shave in the dark. We watched our fishermen lift boats with shoulders that had carried grief. The first plank was placed with ceremony. The last plank was placed with relief.

When the first truck crossed — slowly, like a man greeting a horse he had not ridden in years — the village clapped. We clapped like children at a puppet show, except this time the strings were rope and our hands smelled of sap instead of dust.

That evening, the lieutenant set up a projector in the square and hung a sheet on the Rathaus wall. We sat on crates and benches. The Americans stood or lay on their packs. The projector coughed light like a smoker and then whispered a film onto the sheet: women in hats in a city with wide streets, a man kissing a woman at a station, a baseball game where the ball went up into a sky that looked like ours and then fell back into a glove that looked like Collins’. The soundtrack sputtered and then found a tune. Somewhere behind us, a cow lowed as if adding commentary.

The schoolteacher leaned toward me. “Listen,” she said. “Do you hear? They laugh with their throats open.”

“I know,” I whispered. “It is loud and clean.”

When the film ended, the sheet flapped like a sail. The lieutenant turned and, without the notebook for once, said, “We don’t know how long we will be here. We will do our work and hope you will do yours. Tomorrow we begin repairing the school roof. And — please — bring your children. We’ll teach English for an hour. You can teach us the song you sang when that bridge was bones.”

He looked, for a moment, exactly his age, which was too young to be in charge of anyone. He nodded, then put the notebook back in his pocket as if the act made him older again.

We went to sleep second-night-of-peace sleep: lighter, still cautious, the kind that keeps your ears open but lets your shoulders forget a little.

Days lengthened into routine. Collins fixed our squeaky door with oil and a piece of cotton and showed me how. He measured himself against the chalk marks on the doorframe and laughed when he came up short against Father’s line by the width of a fingernail. He taught Franzl to catch not with fear but with hands that closed at the exact right moment. He learned to pronounce “Pfannkuchen,” which made us laugh every time because he insisted on a military seriousness that the pancake did not deserve.

We learned they missed home almost as much as we missed ours.

One afternoon, a Red Cross truck arrived with parcels and letters. Collins opened an envelope and took a deep breath as if letters sometimes carried oxygen. He read quickly, his mouth moving. Then he tucked a photograph into his shirt.

“Wife?” Mother asked gently.

“Mother,” he said, and then, trying the word that was both the same and not, “Mutter.” He tapped his chest. “Keine Frau.” No wife.

He looked at me and at the chalk on the door and then at Mother’s hands. “You are strong,” he said. “Both.”

Mother shrugged, an art we had perfected. “We learn,” she said.

High summer arrived. The linden tree threw shade wide enough for a classroom. We put words on a blackboard that had once held maps with arrows. “Apple,” I wrote. “Apfel,” the schoolteacher added. “Bridge,” wrote Collins, and underlined it twice. “Brot,” wrote the baker’s wife, just because it felt good to write a word that meant full.

Sometimes there was a small parade of the war through our village: a group of men in gray with empty hands and eyes like abandoned houses passing through, guarded by Americans whose faces had learned to be careful with triumph. We stood aside and lowered our eyes. We, too, were learning carefulness — the careful way to be relieved without dancing on a grave.

In late August, orders came. The column that had made our square look like a blueprint began to turn back into a drawing of departure. The lieutenant shook hands with the mayor — the handshake of men who had negotiated curfews and roof tiles — and promised letters neither would write. The fishermen brought eels for the Americans and acted as though eels were what one always brought to farewell parties.

When it was Collins’ turn to leave, he stood in our doorway and looked once more at the chalk marks, then added one for himself with the date. He gave me a baseball, scuffed from a summer of being asked to explain itself.

“Catch,” he said. “Learn to look it in the eye.”

He gave Mother a small tin of coffee and told her it tasted like mornings in a city he loved. He shook my uncle’s hand with the understanding of men who talk little and repair more. He called out to Penn, who shouted back something that sounded like a swear, and they both laughed.

At the truck, he turned and looked at us the way people look at water before they drink: grateful, wary, aware that the thing will pass through and not stay.

“Tschüss,” he said in the German that children use.

“Auf Wiedersehen,” I said in the German that hopes.

They rolled out the way they had arrived, with engines that remembered winter and roads that remembered boots. We watched until the dust was just dust.

That evening, the village was quieter than we expected. The lieutenant’s notebook lived in my memory, a list of small repairs that had become, in their accumulation, a kind of miracle: bridge, roof, salt, grammar books, shoes. People had started to paint shutters again, not because anyone had ordered it but because color felt legal.

I took the baseball to the doorframe and held it at the level of Collins’ chalk mark. He had been taller than our rumors and shorter than our fear. He had been, to my surprise, a person.

We ate soup that tasted less like stretching and more like seasoning. We talked about the bridge as if talking could make wood stronger. We listened to the radio and found a station where a woman sang in French about the moon as if it were a neighbor.

In bed that night, I lay awake and tried to list, in both languages, the ways enemies turned into something else when you saw them standing in your doorway struggling with a ladle. Enemy: Feind. Stranger: Fremder. Guest: Gast. Neighbor: Nachbar. Friend: Freund. The words behaved like a line of soldiers that had been told to stand down and go home.

When sleep finally came, it brought a simple dream: a chalk mark on a doorframe that kept getting higher, not because anyone taller had arrived, but because the house itself had decided to stand up straighter.

Years later, when our town had rebuilt its own habits and the doorframe held a new generation’s heights, tourists would come and ask, in halting German, where the Americans had stood. We would show them the linden tree and the river and the bridge whose planks had been replaced three times but whose idea had not. We would point to the doorframe where Father’s chalk still ghosted the wood, and we would point to the little mark with a foreign date.

“They were taller than we imagined,” we would say, smiling at our younger selves who had thought that height was the important part. “But not just in inches.”

News

How a Former Colonel Confronted the Collapse of Everything He Once Believed, Faced the Weight of His Past on the Ashes of a Broken Nation, and Spent Three Decades Rebuilding Trust, Bridges, and the Dream of a United Europe

How a Former Colonel Confronted the Collapse of Everything He Once Believed, Faced the Weight of His Past on the…

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose From the Dust to Prove Skill, Honor, and Command Presence Matter More Than Intimidation or Muscle

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose…

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders, and Quietly Shifted the Balance of a War Few Understood Was Already Changing

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders,…

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a Force Far Stronger and Sparked One of the Most Astonishing Moments of Bravery in Naval History

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a…

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable Trial That Exposed the Fragility of Power and the Hidden Strength of Ordinary People During the Hamburg Crisis

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable…

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into the Pivotal Moment Changing an Entire War at the Battle of Midway

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into…

End of content

No more pages to load