They Said a Rusty Liberty Ship Would Last Five Minutes Against 23 Bombers — but One Stubborn Captain, a Hidden Cargo of 19 Desperate Refugees and a Rookie Gun Crew Turned the North Atlantic into a Miracle No One Could Explain

The plaque was so small you could almost miss it.

Claire Harper stood on the polished floor of a maritime museum in Boston, surrounded by polished brass and faded flags, and squinted at the little rectangle of metal screwed under a black-and-white photograph.

The photo showed a squat, ugly Liberty ship knifing through gray water, its deck guns silhouetted against a sky full of smoke. Off in the distance, tiny black specks marked where bombs were falling. Someone had snapped the picture from an escorting destroyer that arrived too late to see the worst of it.

Beneath the photo, the plaque read:

SS Meridian Star

North Atlantic, March 1944Attacked by 23 enemy bombers.

4 hours under repeated assault.

0 ships lost in convoy.

19 refugees hidden aboard — all survived.

Claire felt a little shiver run up her arms. Meridian Star.

Her grandfather’s ship.

She’d grown up with pieces of the story — half-remembered tales told over Thanksgiving, always drifting into arguments about whether Grandpa Elias had been a hero or a madman. But this was the first time she’d seen the ship as the world had known it: a line in a museum, reduced to numbers and a grainy photograph.

She leaned closer. Someone had added a smaller note beneath:

German pilots later reported disbelief that a “slow, lightly armed cargo ship”

could withstand repeated coordinated attacks.

Wartime intercepts describe it as “the Liberty ship that simply refused to sink.”

Claire smiled despite herself.

“That sounds like him,” she murmured.

A voice sounded behind her, accented, gentle. “You knew someone from that ship?”

She turned. An elderly man stood a respectful distance away, hands folded over the handle of a cane. His hair was white, his coat perfectly pressed. The pin on his lapel showed a tiny flag — not American. German.

“My grandfather was Captain Elias Harper,” she said. “He commanded Meridian Star.”

The old man’s eyes widened. He looked again at the photo, then back at her.

“Then perhaps,” he said softly, “it is time you hear the other half of the story.”

The morning they took on the refugees, the harbor in Belfast was still half asleep.

Fog rolled low over the water, muffling the clank of chains and the groan of winches. The SS Meridian Star, Liberty-class cargo ship, sat heavy at the pier, her holds already crammed with ammunition crates and food bound for England. She looked tired — rust streaking her flanks, paint peeling where salt and time had chewed at her.

On the bridge, Captain Elias Harper cradled a mug of coffee and watched the dockside commotion through narrowed gray eyes. He’d been at sea since he was seventeen. By forty-nine, nothing about war convoys surprised him much — not the blackout shades, not the anti-submarine net, not the destroyer already waiting outside the harbor like a sheepdog.

Then he saw the truck.

It was small, army-green, with canvas sides and tires too bald for comfort. It pulled up near the gangway and hissed to a stop. A young lieutenant hopped out, his uniform too crisp for a veteran, and hurried toward the ship.

Harper set down his coffee.

“I have a bad feeling about that truck,” he muttered.

First Officer Tom Briggs, who had been studying the departure orders, followed his gaze and snorted.

“Probably more ammo,” Briggs said. “Or someone realized we forgot half the potatoes.”

Harper didn’t answer. He watched as the lieutenant spoke to the dockmaster, gestured toward the ship, then waved at the truck. The canvas flap at the back lifted.

Nineteen faces peered out.

Most were small. Children. A few women. One older man with a beard and a hat clutched in his hands as if he’d been holding it for hours. Their clothes didn’t match — coats too thin for the Irish cold, shoes scuffed by long roads.

Refugees, Harper thought. The word tasted complex — pity, risk, paperwork.

The lieutenant glanced up at the bridge and cupped his hands around his mouth.

“Captain! Permission to come aboard and speak?”

Harper didn’t sigh out loud, but he felt like it.

“Here we go,” he said under his breath, and headed for the ladder.

Up close, the lieutenant looked even younger, his cheeks roughened by a shave done in a moving truck. Two military policemen stood behind him, hands resting on their belts. The refugees huddled in the truck, eyes darting between ship and soldiers.

“Captain Harper,” the lieutenant said, snapping a quick salute. “Sir. Lieutenant James Avery, Army liaison.”

Harper returned a shorter, older salute.

“What can I do for you, Lieutenant?” he asked. “We’re due to sail in three hours.”

“Understood, sir.” Avery took a breath. “We have civilians who need passage. Misplaced paperwork, mixed up transport assignments — they were supposed to be evacuated on a hospital ship yesterday, but someone in London changed priorities. There’s no room on anything else leaving this week.” He nodded toward the truck. “It’s either them on your ship or them waiting here through the next air raid.”

Harper’s jaw tightened. Belfast had been hit often enough. He pictured bombs falling, children pressed against cold stone walls.

“How many?” he asked.

“Nineteen,” Avery said. “Mostly children from occupied territories. One doctor, two mothers, one older gentleman. They’ve been cleared, security-checked. We just… we ran out of space.”

He didn’t say the rest. They always ran out of space in war.

Briggs appeared at Harper’s shoulder, orders still in hand.

“Captain, our manifest doesn’t allow passengers,” Briggs said. He kept his voice low, but not low enough that the refugees couldn’t hear. One of the children, a thin girl with dark braids, watched him with enormous eyes. “We’re a cargo vessel, not a ferry.”

“Command authorization?” Harper asked Avery.

The lieutenant produced a folded paper, stamped, signed, with a name Harper recognized from enough memos to know it was real.

“Temporary civilian transport authorization,” Avery said. “One voyage. They’ll disembark in Liverpool. Sir… I don’t have anywhere else to put them.”

Harper took the paper. The language was legal, icy, and impersonal. It boiled down to two things: we made a mistake, and you will fix it.

He looked up at the truck. The refugees were trying very hard not to look hopeful. They knew better than to hope too easily.

Harper had hauled ammunition through U-boat-infested waters, sailed in convoys that lost two ships in a night. He’d told families their sons weren’t coming home. He’d signed off on cargo that never reached its destination.

He had never, in all those years, turned children away from a gangway he commanded.

“Where would we put them?” he asked.

“In the after hold, sir,” Avery said quickly. “We’ve cleared a corner, set up cots. They’ll stay below during transit to keep things simple.”

Briggs shifted his weight.

“Sir, with respect,” he said. “We’re already more loaded than I like. Add civilians and we’re multiplying our problems. If we take a hit—”

“If we take a hit,” Harper cut in, not abruptly but firmly, “we’ll deal with it. As we’ve always done.”

Briggs’ mouth tightened.

“You’re the captain,” he said. “But if something goes wrong, they’ll say we broke rules. And they’ll be right.”

That was the thing about Briggs. He didn’t whine. He simply laid out consequences like coordinates on a chart.

Harper studied the refugees again. The braided girl met his gaze for a heartbeat. She didn’t smile. She just held his eyes as if weighing him.

He turned back to Avery.

“Get them aboard, Lieutenant,” Harper said. “Quietly. I’m not turning anyone away to sit under the next siren.”

Avery’s shoulders dropped in relief.

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

As the MPs moved to help the refugees down, Briggs stepped closer.

“This is a mistake,” he said under his breath. “We’re going into open water with air raids nightly and subs that haven’t gotten the memo about losing the war. You’re adding nineteen more hearts for this ship to break.”

Harper didn’t look away from the refugees as they stepped carefully onto the gangway.

“Or nineteen reasons to fight a little harder,” he said.

The argument didn’t end there. It just went quiet, like an unresolved chord hanging in the air.

Her name was Anikó, but everyone on board ended up calling her Annie.

She was fourteen, though war had made that feel like a number that cheated. Her father had been taken two years earlier after someone whispered that he listened to the wrong radio station. Her mother had traded everything to get them onto the evacuation list. A train, a truck, a crowded room in Naples where names were shouted and checked. Her mother had squeezed her hand so tightly that Annie’s fingers still ached on cold mornings.

Now they were on a ship that smelled of oil and metal and something sharp she couldn’t name. The hold the soldiers put them in was cramped but clean enough. Cots were lined up in two rows, canvas stretched over metal frames, blankets folded at the foot.

The old man in the hat introduced himself as Professor Weiss. He had once lectured about history, he said, until history came crashing through the windows of his classroom. The doctor was a soft-spoken Italian woman named Lucia who carried her bag like a shield. The other refugees were a blur of names and accents.

“Stay below,” a soldier told them. “No wandering on deck. It’s safer this way.”

“Safer from what?” Annie asked. Her English was good enough; she’d learned it from old records and a teacher who sneaked in books.

“From everything,” the soldier said, and shut the hatch.

The hold grew quiet. Somewhere far above, boots thudded on metal. A whistle blew. The subtle tilt of the ship changed as they pulled away from the dock.

Annie sat on her cot, hugging her small suitcase to her chest. Her mother, Maria, smoothed her hair and tried to smile.

“See?” Maria said. “We are moving. That means we are going where we are supposed to go.”

“Where is that?” Annie asked.

“Somewhere safer,” Maria said. “Across the water. We will start again.”

Professor Weiss, on the cot opposite, chuckled softly.

“Families have been saying that since people first built boats,” he said. “Across the water, somewhere safer. Sometimes it turns out to be true.”

“Sometimes?” Annie echoed.

Weiss shrugged with one shoulder.

“We live on maybes now, child. But maybe is still better than never.”

The ship’s engines rumbled like a distant thunder. As Meridian Star slid into the gray Atlantic, nineteen refugees settled into uneasy hope, unaware that in a few days their survival would become a point of argument in war rooms on two continents.

On the second day out, Briggs brought up the refugees at the noon briefing.

They were in the cramped chartroom off the bridge, the table crowded with maps and coffee rings. The convoy — a loose line of Liberty ships, tankers, and a few faster freighters — crawled across the Atlantic at a stubborn ten knots. A destroyer ahead and a corvette hanging back tried to look like enough protection against submarines and aircraft.

Harper traced their plotted course with a calloused finger.

“If we hold this speed, we’ll be off the Irish shelf by tomorrow night,” he said. “After that, we’re in the deep water.”

“Where the wolves are,” muttered Chief Engineer Morales.

“And the birds,” added the signalman, Petty Officer Quinn. “Radio picked up chatter this morning about increased enemy air patrols out of the French coast. They’re pushing farther west now that they’re desperate.”

“We’re not exactly a tempting target,” Morales said. “We barely make steam, and we’re carrying beans and bullets, not gold.”

Quinn shrugged.

“A ship’s a ship from the sky,” he said. “And every ship we sink is one less that makes it to England. That’s how they think.”

Briggs cleared his throat.

“Speaking of things we carry,” he said. “We should address our extra cargo.”

Harper didn’t pretend not to know what he meant.

“They’re people, not cargo,” he said.

Briggs’ jaw flexed.

“They’re nineteen souls we weren’t scheduled to protect,” he said. “We’ve already heard planes at night. If we get spotted, that hold becomes a trap. We have no proper shelter, no lifeboat assignment, no—”

“No guarantee about anything,” Harper finished. “Same as the rest of us.”

Morales shifted, uncomfortable.

“Captain, if we do take a hit,” he said, “the after hold’s not the worst place they could be. It’s near the bulkhead. But Briggs is right about one thing: they’ll need a plan. We can’t just pretend they’re not there.”

Harper knew that. He’d been pretending a little anyway, because every time he thought about those nineteen faces, he saw them in the water. He saw himself writing their names in a log no one would read.

He rubbed his temple.

“All right,” he said. “Here’s what we’ll do. Morales, check the ladders and hatches near the after hold. Make sure nothing sticks. Quinn, you’re in charge of a drill. Quiet — no announcing it ship-wide. I don’t want the refugees panicking. Just show them the way to the nearest lifeboats, assign them spots, make sure they know how to put on lifejackets.”

Briggs’s eyebrows shot up.

“Lifejackets?” he repeated. “For people who aren’t on the manifest?”

Harper met his gaze squarely.

“You want them drowning because someone in an office didn’t type their names?” he asked.

Briggs dropped his eyes first.

“That’s not what I want,” he said. “I just don’t want to give command another reason to say we’re reckless. We’re already low on credit.”

“We’re in a war,” Harper said. “Credit is imaginary. The only currency that matters is who makes it home. We do our jobs, and if someone wants to write me up later, they can do it with all nineteen of those kids waving behind me.”

The room went quiet for a heartbeat. Then Morales nodded slowly.

“I’ll check the hatches,” he said.

Quinn, barely twenty and trying not to show how nervous he was, saluted.

“I’ll take care of the drill, Skipper,” he said. “I’ve got a little sister back home. I’ll treat them like she was on board.”

“Good,” Harper said. “Then maybe we can all sleep half an hour tonight.”

Briggs folded his arms.

“And if the planes come before we’re ready?” he asked.

Harper looked at him.

“Then,” he said, “we find out what we’re made of.”

The drill took place that afternoon under a sky the color of steel.

Quinn led the refugees up narrow ladders, along passageways that smelled of paint and salt, and out onto a section of deck near the aft lifeboats. The wind slapped at their faces. The Atlantic rolled in long, slow swells, the convoy spread out in a ragged line ahead and behind them.

Annie stepped carefully, one hand on the cold rail, the other gripping her mother’s sleeve. She was dizzy from the motion and the sudden expanse of sky. She’d never seen the horizon like this — a clean, sharp line between water and air, unbroken by buildings or mountains.

“Stay in pairs,” Quinn called, his voice climbing over the wind. “Everyone gets a lifejacket. You put it on like this—” He demonstrated, tugging the straps. “If we sound the alarm and tell you to come here, you don’t run, you don’t scream, you just do what you practiced. All right?”

Some of the children nodded. One boy stared fixedly at the lifeboats, his lip trembling.

“We’re not going in them now, are we?” he whispered to Lucia, the doctor.

“No,” she said gently. “This is a rehearsal. Like when we practice a song before we perform it.”

“Or a speech,” Professor Weiss added. “We hope never to give it. But we learn it by heart.”

Annie watched Quinn move among them, adjusting straps, offering a hand when someone stumbled. He had a boyish face, freckles across his nose, and a patient way of explaining that made complicated things seem less frightening.

“Have you done this before?” Annie asked when he checked her jacket.

He glanced at her.

“The drill?” he said. “A few times. The real thing… once. Didn’t like it.”

“What happened?” she asked.

“Another ship in another ocean,” he said. “We got everyone off. Took three days to find land. I don’t recommend it.”

He tried to make it sound like a joke. It almost worked.

When the drill ended, and they were back in the hold, Maria squeezed Annie’s hand.

“See?” Maria said. “They have a plan. That’s good.”

Annie thought about ropes and cold water and the way Quinn’s voice had tightened on the word “once.”

“Good,” she echoed.

Above them, on the bridge, Briggs watched the refugees disappear below again and shook his head.

“You know what happens when you run extra drills?” he said. “You tempt fate.”

Harper, hands on the wheel, kept his gaze on the horizon.

“You think fate cares about drills?” he asked.

“I think fate likes irony,” Briggs said. “We practice for something, and it shows up.”

Harper almost smiled.

“Then let’s practice for making it to Liverpool,” he said.

If fate was listening, it chose to ignore that particular request.

They heard the planes before they saw them.

It was four days out, late morning. The sea had flattened into an ugly, chopped-up gray, the wind biting at exposed skin. The convoy plowed on — Meridian Star somewhere in the middle, destroyer weaving out ahead, steel hulls threading through the vastness of the North Atlantic like beads on a string.

On the bridge, Harper and Briggs were reviewing the latest signal from the escort when Quinn’s head snapped up.

“Listen,” Quinn said.

At first it was nothing — just the usual sounds of sea and ship. Then there it was: a faint buzzing, like angry hornets very far away.

Briggs swore under his breath.

“Engines,” he said. “That’s not ours.”

Harper grabbed the binoculars and scanned the low clouds off the starboard bow.

“Signal from the escort,” Quinn said, pressing headphones to one ear. “Enemy aircraft likely inbound. All ships prepare for air attack.”

The ship’s whistle blared three long blasts. On deck, men dropped what they were doing and ran for their gun stations. Covers came off the 20-mm anti-aircraft guns. Ammunition belts rattled like chains. Someone shouted for helmets.

Below, in the after hold, the refugees jolted as the whistle echoed through the metal.

“What is that?” Maria asked, eyes wide.

Annie had heard that sound on shore. In Naples, in the night, followed by sirens and the dull thump of distant explosions.

“Planes,” she whispered.

The hatch above them banged open. Quinn appeared, breath clouding in the cold air.

“Everyone stay here,” he said, more urgent than he meant to. “Do not come on deck unless we send someone for you. Doctor, Professor, help keep things calm. We’ll get through this.”

“How bad is it?” Weiss asked.

Quinn hesitated.

“I don’t know yet,” he said. “But the convoy’s been lucky so far. Maybe it’s just a flyover.”

He didn’t believe that, and neither did they. But sometimes hope needed a costume.

He shut the hatch and sprinted for his gun station.

On the bridge, distant specks grew into shapes. Harper could make out twin engines, straight wings, stubby noses. Bombers.

“Count?” he asked.

Briggs’ lips moved silently as he tracked them.

“Too many,” Briggs said finally. “At least twenty. Maybe more coming in behind the first wave.”

Quinn’s voice crackled over the voice tube from the gun deck.

“Skipper, they’re lining up on the convoy,” he said. “Looks like they want the big tankers first.”

“That’s small comfort,” Morales muttered.

Harper took a breath.

“All right,” he said. “Sound general quarters. Gunners, hold your fire until they commit to a dive. Don’t waste ammunition trying to scare them.”

Briggs glanced at him.

“And if they decide we’re not worth a bomb?” Briggs asked.

“Then we do our job and keep the sky busy,” Harper said. “Every second we make them spend dodging flak is a second they’re not lining up perfectly on someone else.”

“Heroic,” Briggs said. “Or suicidal.”

“Ships that don’t shoot back sink just as fast,” Harper said. “At least this way we get a vote.”

The bombers broke formation like a flock of birds, peeling off in pairs and trios. Some angled toward the lead ships. Others, perhaps surprised by the stubborn little hedgehog of guns that Meridian Star was rapidly becoming, adjusted their course.

“Looks like we have admirers,” Quinn called.

“All gunners, stand by,” Harper said.

The first bomb fell wide — a distant splash that sent up a towering plume of water. The second landed closer, the concussion shuddering through the hull. Men flinched. Somewhere in the hold, a child started to cry.

“Steady,” Harper said, more to the ship than to anyone. “She’s taken worse waves in a winter storm.”

Then the real attack began.

From the cockpit of his bomber, Oberleutnant Karl Müller studied the Liberty ship through the sweat-fogged glass and felt… annoyed.

The convoy had taken them by surprise at first — a gift in a war that had stopped being generous. Fuel was short. Engines were tired. Pilots were worn out. But here, spread out below, lay an entire line of Allied shipping, crawling along at target-practice speed.

The first dive had been satisfying. One tanker hit, columns of smoke twisting upward. A freighter near the front limping already. Reports crackled over the radio — “Hit amidships,” “Near miss,” “Breaking away.”

Müller’s flight had been assigned the midsection.

“Pick something soft,” his rear gunner, Dieter, said. “Something that won’t shoot back much.”

“Those,” Müller said, nodding at a cluster of ships, “are ammunition carriers. We can tell by the way they turn. Heavy in the water. Sluggish.”

He swung his bomber into a lazy arc, lining up on a Liberty ship that looked particularly tired. Rust streaks, no escort close by, just a handful of small guns.

“See?” he said. “Easy.”

Then the “easy” ship opened up.

Tracer fire stitched the sky, not wild but measured. The first burst passed below him, the second above. The third walked its way toward his nose with disturbing discipline.

“Scheisse,” Dieter yelped as bullets hammered somewhere under their feet. “This one has teeth!”

Müller yanked the yoke, pulling them out of the line of fire, then dove again from a different angle.

“Just one Liberty,” another pilot said over the radio. “Shouldn’t be hard.”

“Tell that to the holes in my wing,” Dieter muttered.

As Müller pulled around for another pass, he looked again. The Liberty ship’s decks were bristling with men at guns, moving with purpose. Smoke puffed from its barrels, but it didn’t waver in formation.

Stubborn, Müller thought. But everything sank eventually.

“Again,” he said through gritted teeth.

On Meridian Star, the world had shrunk to noise and motion.

Bombs screamed as they fell, then exploded in pillars of water that slapped the ship on both sides, dousing the deck in spray. The gunners fired, reloaded, fired again. Shell casings rolled underfoot like brass marbles.

Quinn’s shoulder ached from the recoil of the 20-mm. His ears rang despite the cotton stuffed into them. He tracked the nearest bomber, leading it just enough, and squeezed the trigger.

Tracer rounds reached up, curved, and for a heartbeat he thought he’d missed. Then the bomber jerked, trailing smoke from one engine.

The gun’s loader, a kid from Ohio whose name Quinn hadn’t had time to remember properly, shouted in disbelief.

“You got him! You actually got him!”

The bomber wobbled away, climbing, leaving a smudge of black against the cloud.

“Or I annoyed him,” Quinn said. “He’ll be back if he can turn.”

Another bomb fell close. The explosion blew a chunk of deck planking into the air. A spray of splinters peppered Quinn’s cheek. He tasted salt and dust.

“Damage report!” Harper shouted down the voice tube.

Morales’ voice came back from the engine room, taut but steady.

“Holding for now,” he said. “Starboard plating buckled, but no breach. Pumps are ready if we start taking on water.”

Briggs, white-knuckled on the bridge rail, watched a nearby freighter take a direct hit. The ship seemed to rise on its own explosion, then sag. Flames licked at the cargo hatches.

“Poor devils,” he muttered.

The bombers wheeled again.

“This is impossible,” Briggs said. “Twenty-three of them? Against us?”

“Not just us,” Harper said. “The whole convoy.”

Briggs shot him a look.

“The escort’s busy,” he said. “The others too. We look like an easy mark. So they keep coming.”

As if to prove his point, three bombers peeled off from the main group and dove together toward Meridian Star.

“Triple run!” Quinn yelled. “Here they come!”

“Hard port!” Harper snapped.

The helmsman spun the wheel. The Liberty ship, never designed for elegance, responded with a sluggish, stubborn swing. The bombs fell — one ahead, one astern, one so close on the port side that the blast lifted the ship and slammed her down again.

In the after hold, the refugees were flung from their cots. Dust sifted down from the ceiling. Annie clutched her suitcase, teeth rattling.

“What’s happening?” a boy cried.

Professor Weiss crawled to him, his own hands shaking.

“The ship is dancing,” Weiss said. “The captain is teaching it to dodge.”

Maria caught Annie’s eye and tried to nod reassuringly. The effect was spoiled by the way her lips were pressed so tightly together.

“I’ll be right back,” Lucia said, grabbing her bag. “If they need help on deck…”

“Stay,” Weiss said, fingers closing around her sleeve. “If the doctor goes up and does not come back, who will the children have to look at?”

Lucia hesitated, then slowly sat down again.

“Then we all stay,” she said. “Until someone tells us otherwise.”

Above, the argument Briggs had been holding back finally broke loose.

“This is madness!” he shouted over the scream of falling bombs. “We’re one Liberty ship. We’re supposed to stay in formation, not play decoy.”

Harper’s jaw clenched.

“We are in formation,” he said. “We’re just not rolling over.”

“They’ll sink us first!” Briggs snapped. “And when they write the report, it’ll say we died bravely while violating common sense.”

A near miss slammed water across the bridge windows, cutting off his view for a second. When it cleared, everyone was still standing. The ship was still moving.

Harper leaned in close.

“Tom,” he said quietly, using Briggs’s first name for once. “There are nineteen children below deck who think adults know what they’re doing. I am not going to sit here and hope those pilots get bored. If they want us, they’ll have to work for it. Are you with me or not?”

Briggs stared at him. For a moment, fear and anger warred on his face. Then something else settled in — something like resignation, or acceptance.

“I’m with you,” he said. “But if we get out of this, you’re explaining all of it to the board of inquiry yourself.”

“Gladly,” Harper said.

He grabbed the voice tube.

“All stations, this is the captain,” he said. “You’ve seen what they’ve got. Now make them see what we’ve got. Keep shooting. Keep moving. We’re not done yet.”

From the German side, the reports began to sound… irritated.

“Liberty ship mid-column still active,” one pilot said over the radio. “Multiple passes, heavy flak.”

“I thought those things were barely armed,” another responded.

“So did I,” came the tight answer. “This one didn’t get the memo.”

Müller clenched his jaw. He’d already made three runs on the same ship, and each time he’d taken more damage than he’d inflicted. He’d seen bombs fall close — near enough to drench the vessel, to lift it, to rattle its bones. But not close enough to break it.

“Fuel check,” he snapped.

“Getting low,” Dieter said. “Two or three more dives at most if we want to make it home.”

Home. That word had started to feel theoretical.

“Command will not be pleased if we return with our bomb load unused,” Müller said.

“Command is not here,” Dieter muttered.

Müller looped around again, lining up the Liberty ship in his sights.

“Just one more,” he said. “It cannot last forever.”

On Meridian Star, Quinn saw the bomber angle down again and felt a flicker of something like grim camaraderie.

“You have to admire persistence,” he muttered.

“Save it for after we’re not under them,” his loader said.

The next few minutes were a blur.

Bombers dove in turns, trying to coordinate, trying to catch the ship in a pattern. Harper zigzagged as best he could, turning into the dives, presenting the smallest possible target. Gunners blazed away, barrels glowing hot.

A bomb struck the water so close to the starboard bow that it cracked the plating. Seawater gushed in. Alarms wailed in the engine room.

“Skipper, we’re taking on water forward!” Morales yelled. “Pumps engaged. We can compensate for now, but if we take another that close…”

“We won’t,” Harper said. He wasn’t sure how he knew that. He just refused to imagine the alternative.

Another near miss shook the entire ship. A crate broke loose in the hold, smashing against a bulkhead. In the refugee compartment, dust exploded from the ceiling.

A child started sobbing uncontrollably. Lucia moved from cot to cot, murmuring the same words in three different languages: “You are here, you are breathing, you are alive.”

Annie sat frozen, suitcase clutched in white-knuckled hands. She listened to the stomping overhead, the distant shouts, the relentless pounding of guns. She pictured the young gunner, Quinn, standing exposed under the screaming planes, firing up at specks that wanted to erase them.

“You should at least come below,” she whispered toward the ceiling.

No one could hear her, but it felt important to say.

After what felt like a lifetime compressed into minutes, the intensity of the attack began to change.

The bombers were still there, but their dives grew less precise. Some peeled away earlier. The firing runs became sloppier.

On his bomber, Müller checked his fuel gauges and swore.

“We have to break off,” Dieter said. “If we don’t, we swim home.”

“Any other joy today?” came a weary voice from another cockpit. “My wing’s shot full of holes and my navigator is green.”

One by one, the reports echoed the same reality: low fuel, damaged engines, nerves fraying.

Müller made one last pass, more out of stubbornness than strategy. He dropped his final bomb, watched it fall, and cursed when it detonated just shy of the Liberty ship’s stern.

A column of water shot up, drenched the deck, then fell back.

The ship slowed, shuddered — but kept going.

“Pulling out,” he told the formation. “We’ve done what we can.”

“What we can,” Dieter repeated under his breath. “Except sink that cursed thing.”

Müller banked toward the east, leaving the convoy behind. As he did, he looked back one last time.

The Liberty ship was still there. Smoke curled from one corner of her deck where a crate had caught fire, but streams of water were already beating it down. Her guns still pointed skyward, daring anyone to come back.

He shook his head, a reluctant respect forming in his chest.

“Stubborn,” he said again.

The Atlantic swallowed his words.

On Meridian Star, the sky gradually emptied.

One moment there were bombers everywhere — outlines against the clouds, noise above all other noise. The next, there were only a few stragglers, then none.

The air felt raw, scraped clean.

“Cease fire,” Harper said hoarsely. “All guns, cease fire.”

The sudden relative quiet made his ears ring. He realized only then how hoarse he’d become from shouting orders.

“Damage control,” he said. “I want reports from every compartment. Check on the refugees first.”

“Aye,” Briggs said, already moving.

Quinn slumped against his gun, arms trembling. His loader slid down to sit on the deck, breathing hard.

“We’re alive,” the loader said, as if testing the words.

“Ship’s still floating,” Quinn said. “So yeah. For now.”

When Briggs reached the after hold and spun the hatch wheel, dozens of eyes turned up at him.

“How bad?” Professor Weiss asked.

Briggs glanced around. The hold was dusty, dim, and crowded — but intact. No shattered beams, no rushing water.

“We’re still here,” he said. “Which is better than the alternative.”

Maria wrapped both arms around Annie and sagged with relief.

“Is it over?” a child whispered.

“For now,” Briggs said. “Stay here until we say otherwise. It’s safer below.”

Lucia frowned.

“If something had happened…” she began.

“It didn’t,” Briggs said. His voice cracked just enough to betray how close he’d come to imagining it too. “The captain danced this bucket through a storm. You owe him your grumbling later.”

Weiss smiled faintly.

“We will give him a proper grumble, then,” he said. “To show our gratitude.”

As Briggs closed the hatch, he heard soft laughter start up — strained, but real. For the first time since the attack began, he felt something in his chest unclench.

Back on the bridge, Morales’ voice came through, sounding almost cheerful.

“Pumps are keeping up,” Morales said. “We’ve got some leaks and a long list of things that will make the shipwrights in Liverpool curse our names, but we’re afloat and making way.”

“Any casualties?” Harper asked, bracing himself.

Morales hesitated.

“Minor injuries,” he said. “Couple of cuts, a broken wrist. Nothing worse than what the city boys get in a bar fight.”

Harper exhaled slowly.

“And the convoy?” he asked Quinn.

Quinn, at the signal desk, scanned the reports.

“One tanker burning but under tow,” Quinn said. “One freighter damaged. No ships lost. Escort reports several bombers damaged, maybe a few down.”

Briggs reappeared on the bridge, hair mussed, eyes bloodshot.

“The refugees are intact,” he said. “Scared, but intact.”

Harper leaned on the rail and looked out at the gray ocean, the line of ships that had somehow held together under a sky that wanted to tear them apart.

“All ships, this is Meridian Star,” Quinn read from a signal light as he translated Harper’s words into flashes. “We are damaged but operational. Still in formation. Still carrying everything we left with.”

In a cramped radio room somewhere on the enemy coast, an operator transcribing reports from returning bombers jotted down a note beside the line about a stubborn Liberty ship:

Target: one cargo ship. Heavy resistance. Refused to sink.

The comment made its way up through channels, gathering disbelief like lint.

They limped into Liverpool four days later, battered but upright.

Dockworkers stared at the patched hull, the scorch marks, the splintered railings. Stories had outrun them, as stories always do.

“Is this the one that took on two dozen bombers?” someone called up as the gangway went down.

“Twenty-three,” Quinn shouted back before he could stop himself. “But who’s counting?”

When the refugees emerged, blinking in the unfamiliar sunlight, a murmur rippled through the dockside crowd.

“Passengers?” a harbor official said, scandalized. “On a Liberty?”

Harper met his eye.

“Temporary authorization,” Harper said, producing the wrinkled paper Avery had given him. “We were asked to carry them.”

“And we carried them,” Briggs added. “All the way.”

The official started to sputter about protocols and manifests. Harper let him wind down, then spoke in a tone that carried the gravel of the North Atlantic.

“If you’d like to file a complaint, sir,” he said. “You can send it to my cabin. I’ll make sure it arrives framed, so I can hang it next to the memory of nineteen people who didn’t drown.”

The official’s mouth snapped shut. He looked past Harper at the refugees, who were already being shepherded toward a shelter building, wrapped in borrowed coats.

Professor Weiss paused at the foot of the gangway and turned back.

“Captain,” Weiss called.

Harper stepped closer.

“Yes, Professor?”

Weiss lifted his hat in a small, formal gesture.

“Thank you for arguing with your first officer,” Weiss said, eyes twinkling. “It appears you won the right to make a very good decision.”

Harper glanced at Briggs, who was pretending to examine a mooring line.

“Sometimes,” Harper said, “a captain has to be stubborn.”

Annie stood beside Weiss, suitcase still in hand. She looked up at Harper.

“I will learn English better,” she said, careful with each word. “Then I will tell people what you did.”

Harper felt his throat tighten.

“Learn it for something nicer than war stories,” he said.

She smiled.

“Maybe both,” she said. “We need all kinds.”

In the years that followed, Meridian Star’s brush with twenty-three bombers became a small legend in certain circles.

Convoy officers told the tale as a lesson in what a single ship could endure. Refugee organizations used it as an example of how bureaucratic errors could still end in grace. Pilots on both sides remembered that day as one where expectations were upended.

In Germany, in the late 1940s, a former airman named Karl Müller sat in a café and read a translated clipping about a “stubborn Allied cargo ship” that had held off an entire squadron. He snorted.

“Meridian Star,” the article said. The name meant nothing to him until he read the line about the refugees.

All nineteen survived.

He closed his eyes and pictured the squat ship below, the flak whipping past his cockpit, the way it had refused to die. He had not known it carried civilians. He had not known it carried children.

If I had sunk her, he thought, would I be reading this now? Or would the article be shorter — a footnote about souls lost at sea?

He stirred his coffee and said nothing aloud. Some questions sat better in silence.

Back in the Boston museum, decades later, the old man with the cane shifted his weight and looked up at the photograph of Meridian Star.

“I was in one of those planes,” he told Claire. “Not the one that damaged her, clearly. The one that failed to.”

Claire stared.

“You… you attacked my grandfather’s ship?” she asked.

“I attacked a silhouette on the water,” he said. “We did not know names then. We barely knew our own by the end.”

He tapped the plaque with one knuckle.

“Later, in an archive, I read a captured report about that convoy,” he said. “It mentioned the refugees. That no ships were lost. That all nineteen survived. And for the first time, I thought — there are lives I did not take that day. They do not know my name. I do not know theirs. But they exist.”

Claire nodded slowly.

“One of them was my grandmother,” she said. “Her name was Annie. She came to America with a small suitcase and a story nobody believed for a long time. She said a creaky cargo ship danced under the bombs for hours. She said the captain and his first officer argued about whether they should have been aboard at all. She said the crew fought like they had extra hearts to protect.”

The old man smiled, lines deepening around his eyes.

“Your grandmother was right,” he said. “On all counts.”

Claire looked back at the photograph. The Liberty ship in the picture seemed small, almost fragile.

“Germans couldn’t believe one ship held off twenty-three bombers,” she said softly. “That’s what it says in the notes.”

“We believed it,” he said. “With every hole in our wings, we believed it.”

He straightened slowly.

“I came here today,” he said, “because I heard this museum had a photo of that ship. I thought perhaps I would finally say thank you. Not to the crew — they did their duty. But to the stubborn captain who decided to carry nineteen people he didn’t have to. Without that choice, my failure in the sky would have been a very different thing.”

Claire swallowed past the lump in her throat.

“My grandfather was never good at following orders when they got in the way of people,” she said. “He probably would have called your attack ‘good practice.’”

The old man laughed — a soft, surprised sound.

“If you ever want to know what it looked like from above,” he said, “I can tell you. There is more than one way to remember a miracle.”

She thought of Annie, sitting at a kitchen table years earlier, hands wrapped around a mug of tea, eyes distant as she spoke of drills and deck guns and a sky full of angry bees.

“I’d like that,” Claire said. “We’ve heard the story from below for a long time. It’s time we heard another angle.”

They stood together in front of the photograph — the granddaughter of the captain and the man who had tried to sink his ship — and read the small plaque again.

Four hours under attack.

No ships lost.

Nineteen refugees.

Nineteen survivors.

In a world that had spent much of the twentieth century counting losses, the numbers on that plaque were a rare equation that pointed the other way.

All nineteen.

Every last one.

News

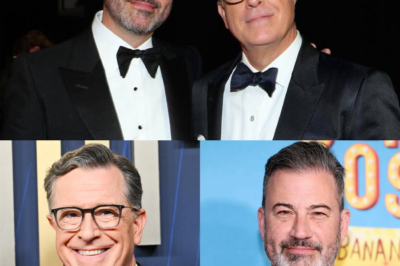

THE NEWS THAT DETONATED ACROSS THE MEDIA WORLD

Two Rival Late-Night Legends Stun America by Secretly Launching an Unfiltered Independent News Channel — But Insider Leaks About the…

A PODCAST EPISODE NO ONE WAS READY FOR

A Celebrity Host Stuns a Political Power Couple Live On-Air — Refusing to Let Their “Mysterious, Too-Quiet Husband” Near His…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced a Secretive Independent Newsroom — But Their Tease of a Hidden…

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,” and Accidentally Exposed the Truth About Our Family in Front of Everyone

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,”…

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He Never Expected the Entire Reception to Hear My Response and Watch Our Family Finally Break Open”

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He…

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting Match Broke Out, and the Truth About Their Relationship Forced Our Family to Choose Sides

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting…

End of content

No more pages to load