They Mocked the Slow “Flame Sherman” as a Clumsy Monster—Until One Dawn It Rolled Forward, Breathed Heat, and Collapsed an Entire Island’s Bunker Plan in Minutes

General Noboru Akiyama disliked ugly machines.

He disliked them the way a calligrapher disliked a blot—something heavy-handed that ruined the balance of a line. In his mind, war had always been a kind of geometry: angles of fire, overlapping sectors, approaches that could be predicted and punished. The island, with its ridges and coral shelves and tangled scrub, was a blackboard. Akiyama’s officers were chalk. His bunkers were punctuation marks.

And the enemy—if the enemy was sensible—would read the lesson.

They had built the bunker line with patience and pride. It wasn’t a single wall, but a woven thing: low concrete boxes with narrow slits, chambers cut into coral, crawl spaces that linked positions like veins. Some emplacements were obvious by design, meant to draw attention. Others were hidden so well that even the men assigned to them had to memorize the path, because once the brush was replaced and the loose coral brushed over, the entrance became a rumor.

Akiyama’s doctrine was simple: the enemy would arrive by sea, step onto sand, then crawl uphill into a maze that never allowed a clean answer. Every advance would be met by fire from two directions. Every pause would be punished. Every machine would be forced to pick a lane—and lanes were where geometry killed.

The Americans, Akiyama believed, were fond of machines. They brought steel to a jungle and assumed steel would persuade nature. That arrogance could be used.

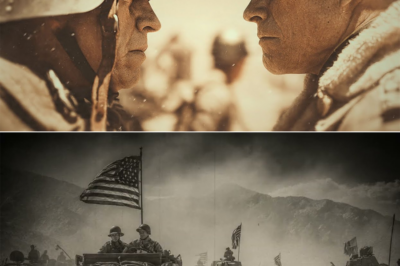

So when his intelligence officer reported that American engineers had been modifying tanks—“special Shermans,” the officer called them, lowering his voice as if the words might summon one—Akiyama felt only mild curiosity.

“Tanks?” he said, studying the map on his table. “On coral and slopes?”

“Yes, sir. They are bringing more. Some have strange fittings.”

Akiyama’s chief of staff, Colonel Ishikawa, snorted. “The Americans think every problem is a door,” he said. “So they build bigger shoulders.”

The room chuckled softly, grateful for any laugh that didn’t taste like desperation.

Akiyama allowed himself a small smile. “A tank is a large target,” he said. “A slow beast. It must come close. And when it comes close, it can be blinded, trapped, and stopped.”

The intelligence officer hesitated. “Sir… some of these tanks may not be armed in the usual way.”

Ishikawa raised an eyebrow. “What do you mean?”

The officer looked down at his notes. “Reports mention… a projecting device. It is described as a ‘flame’ apparatus.”

The word sat in the room like smoke.

Akiyama’s expression stayed calm, but his mind shifted a fraction. Fire was not new. It was as old as war itself. Men had always thrown it, carried it, feared it. But the idea of mounting it on a tank—on a machine meant to crawl forward and refuse to be stopped—added a new layer of discomfort.

Still, discomfort was not the same as danger.

“A tank that projects heat is still a tank,” Akiyama said, voice even. “It must see. It must approach. It must expose itself. Our bunker line is deep.”

Ishikawa nodded. “And we have prepared for it.”

Akiyama tapped the map. “The Americans will bring their slow beast. We will show them that the island is not a road.”

The meeting ended. Orders were issued. Ammunition was redistributed. Mines were checked. The bunker captains were told—again—what they already knew: hold fire until close range, use crossfire, don’t waste shots on shadows.

Outside, the island’s wind moved through palm fronds like a restless audience.

And far beyond the horizon, something heavy was being loaded onto a ship, its tracks clanking like teeth.

Captain Kenji Sato was an engineer officer, and engineers were taught to believe that everything had a reason.

Sato’s bunker—Position 14—was not glamorous. It had a narrow firing slit, a storage alcove, a cramped sleeping corner, and an air vent that always smelled faintly of damp coral. But it was part of the line, and the line was the general’s masterpiece.

Sato had helped build it.

He remembered the first days: cutting into coral with tools that complained, mixing concrete with seawater because fresh water was too precious, dragging logs for reinforcement, working under tarps to hide the shape from reconnaissance planes. He remembered the pride of seeing the bunker’s face disappear under carefully replanted brush, leaving only a faint unnatural straightness that only a trained eye could detect.

Now he lived in it with thirteen men and a radio that worked when it felt like it.

On the night before the Americans pushed again, Sato sat at the entrance and listened.

The sea was invisible, but he could hear it in the pauses between insect calls. Beyond that, he could hear the distant thuds of ship guns—steady, patient, like someone tapping on a door they were certain would eventually open.

A young private named Hori crawled closer. “Captain,” he whispered, “is it true they have a tank that breathes fire?”

Sato didn’t like the word “breathes.” It made a machine sound alive.

“I’ve heard,” Sato said.

Hori swallowed. “Can it reach us?”

Sato looked out at the dark slope ahead, where their wire and mines and hidden lanes waited.

“It would have to come close,” he said. “And close is where we live.”

Hori nodded, but his eyes remained wide.

Sato understood. The bunker line was designed to punish steel, but fire—heat—had a way of ignoring the usual arguments. It didn’t care how brave you were or how accurate your aim was. It cared only about air, space, and time.

Sato returned to the bunker’s interior, where his men sat in silence and pretended they were not listening to the distant guns.

He checked the ammunition again. He checked the water again. He checked the ventilation flap again, as if a flap could solve what the horizon might deliver.

Then he sat under the dim lantern light and wrote a note in his personal notebook—one he never intended to show anyone:

“We have built a maze. But fire does not need to read.”

He stared at the sentence until the lantern hissed, and then he closed the notebook as if closing it might close the thought.

Dawn came gray and heavy, as if the sky itself didn’t want to witness what would follow.

The American bombardment softened, then shifted. It became more selective—fewer random crashes, more deliberate strikes. The island shook in measured pulses. Dust drifted from the bunker ceiling in fine, slow flakes.

Sato pressed his ear to the wall. He could feel vibrations: not just explosions, but movement—many boots, equipment, the subtle rhythm of an advance.

“Positions,” he whispered.

His men slid into place, rifles angled toward the slit, grenades laid out, machine gun ready. The bunker’s interior tightened into purpose.

A voice crackled on the radio—Colonel Ishikawa, clipped and steady.

“Hold fire until you see them. Let them commit.”

Sato answered softly, “Position 14 acknowledges.”

Then the first American figures appeared.

They moved cautiously through scrub, low and careful, using every dip and ridge line. They were disciplined—no wild rush, no careless exposure. Behind them, more figures followed, and behind them, the metallic clank of something heavier.

Sato felt his men tense.

“Wait,” he murmured.

The Americans advanced in short bursts. Some paused to point, to gesture. A few knelt and aimed toward likely bunker faces, trying to provoke shots. Sato gave them nothing.

Then the heavy sound grew louder.

It was not artillery. Not a shell.

It was a machine rolling over uneven ground.

And then it appeared.

A Sherman tank, broad and square, moving with the slow inevitability of a boulder pushed downhill. It had the familiar shape—turret, hull, tracks—but something about it looked wrong. The front carried an unusual fixture, like a stiff snout. The tank’s gun looked secondary, almost uninterested. The “snout” was the real mouth.

Sato’s stomach tightened.

“Is that it?” Hori whispered.

Sato didn’t answer. He didn’t want to give the thing a name.

The tank advanced with infantry close on its flanks, using it like a moving shield. The Americans were not charging. They were methodically closing distance, keeping their spacing, checking each patch of brush as if they had all day.

Sato watched through the slit and felt his own plan—the geometry, the crossfire—begin to strain. The bunker line was designed for enemy hesitation, for confusion. But this advance had a strange confidence. It felt like the Americans had brought a key.

The tank stopped, angled slightly toward a hidden rise where another bunker—Position 12—was known only to their men.

Sato’s breath caught.

How did they know?

Then the tank’s snout shifted.

And the world changed.

A roaring stream—bright in the gray morning—shot out in a focused arc and slammed into the brush-covered face of the hidden position. It wasn’t a random wash. It was aimed, controlled, sustained. It clung to surfaces with a relentless certainty that made Sato’s mouth go dry.

He heard shouting from the direction of Position 12. Not just one voice—many. Then, abruptly, the shouting cut off.

The tank held its stream for a few seconds more, then ceased, as if satisfied.

Smoke—or something like it—rose in a thick, ugly column.

Sato’s hands tightened on the edge of the firing slit until his knuckles hurt.

The slow beast, he realized, did not need speed.

It needed only reach.

The Americans moved forward immediately, infantry flowing around the tank like water around a rock. They didn’t rush the position blindly; they approached with an awful calm, as if they already believed the bunker was no longer a problem.

Sato’s radio crackled with frantic voices.

“Position 12—respond!”

“Position 12, report!”

Static.

A strangled, brief reply—too broken to understand—then silence again.

Colonel Ishikawa’s voice returned, tighter now. “All positions—hold. Hold fire.”

But Sato could hear it even through the radio’s hiss: the colonel’s certainty had developed a crack.

Sato peered again through the slit and saw the Sherman begin to roll forward, one track grinding over coral with a slow, confident chew.

It was coming toward his sector.

Hori whispered, “Captain… it’s coming here.”

Sato forced his voice steady. “It must come close,” he said, repeating the doctrine like a charm. “Close is where we live.”

But the sentence sounded less convincing now, because the tank had proven something cruel:

Close was not only where they lived.

Close was also where the tank’s mouth worked best.

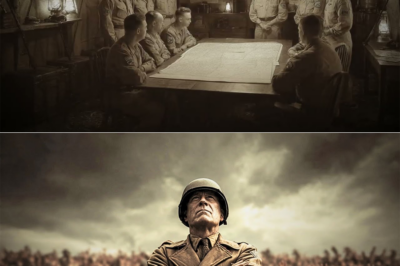

General Akiyama received the first report at midmorning.

His command post was dug into a hillside, protected by sandbags and careful camouflage. From inside, it smelled of earth and wet uniforms and ink. Outside, the island groaned under distant impacts.

A messenger arrived, sweating, eyes sharp with urgency.

“Sir,” the messenger began, “Position 12 is silent. We have no contact.”

Akiyama frowned. “Artillery?”

The messenger hesitated. “Not artillery, sir. A tank with a projecting device. It engaged the position directly.”

Akiyama’s expression tightened. “Engaged how?”

The messenger looked uncomfortable, as if the words themselves were dangerous. “With… intense heat.”

Akiyama’s fingers pressed into the edge of the map.

“Is the position destroyed?”

The messenger swallowed. “We don’t know. The entrance is blocked by rubble and smoke. The Americans advanced past it.”

Akiyama stared at his bunkers marked on the map—each one a point in his geometry. If the enemy could neutralize a point without a slow siege, the geometry began to fail.

“What of the anti-tank teams?” Akiyama asked.

The messenger’s voice dropped. “They attempted an approach. They could not close. The infantry around the tank is heavy.”

Akiyama dismissed him with a short motion and turned to Ishikawa.

“They’re using it as a wedge,” Ishikawa said, jaw clenched. “A slow wedge that scares men away from their own openings.”

Akiyama’s eyes narrowed. “It is still a tank.”

Ishikawa nodded. “Yes. But it is a tank that changes the meaning of ‘near.’”

Akiyama stood, smoothing his tunic as if the gesture could smooth the situation.

“Send orders,” he said. “No bunker holds its fire if the tank approaches. We engage immediately at maximum distance. Focus on the infantry screens. If we remove the screen, the tank becomes alone.”

Ishikawa hesitated. “Sir, our firing slits are—”

“Do it,” Akiyama snapped, sharper than he intended.

Ishikawa bowed. “Yes, sir.”

Akiyama watched him go and felt something he hated: uncertainty.

The Americans, he realized, were not merely attacking his bunker line.

They were rewriting its assumptions.

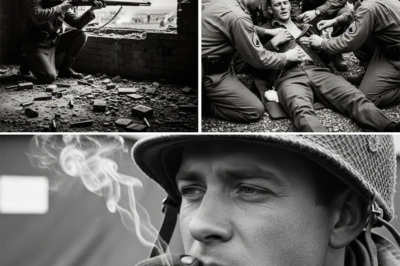

Sato heard the tank before he saw it again.

The clank, the grind, the slow insistence. It came closer in small increments, pausing, angling, moving again—like a predator that didn’t need to hurry because it had teeth that made rushing unnecessary.

“Captain,” Morita—his gunner, older and blunt—muttered, “we should fire now.”

Sato stared through the slit. The tank’s turret was turned slightly away, but its snout faced forward. The infantry moved in cautious swarms, kneeling, scanning, firing into likely shadows.

If Sato fired too early, he might reveal his slit and invite a direct answer.

If he fired too late, he might invite something worse.

He remembered the general’s doctrine. He also remembered the note in his notebook:

Fire does not need to read.

Sato made a decision.

“Fire,” he said quietly.

The machine gun barked through the slit, short controlled bursts aimed at the infantry around the tank. A few Americans dropped into cover. Others returned fire instantly, rounds snapping against coral and sandbags.

Sato’s bunker became a loud place.

Morita kept firing, moving his aim in steady sweeps, trying to thin the infantry screen. Rifles joined in. Grenades were prepared, but Sato knew grenades were prayers at this range.

Outside, the tank paused.

Then it turned—slowly, deliberately—until its snout pointed directly at Sato’s concealed face.

Sato’s stomach clenched.

“Stop firing!” he ordered.

Too late.

The bunker had announced itself.

The tank’s snout dipped slightly, as if tasting the air.

Then a tight stream of brightness shot forward, striking the brush and coral near the slit. The impact was immediate—heat and glare, the air outside the bunker turning into a violent shimmer. The brush that had hidden their entrance ceased to be hiding. Smoke and dust poured, and the outside world became a harsh, choking haze.

Inside, the temperature rose in a frightening rush.

Men shouted. Someone coughed. Another man knocked over a water can in frantic motion.

Sato’s mind raced: ventilation. Airflow. The bunker was strong against bullets and shells, but it was still a box—still dependent on breath.

“Back!” Sato shouted. “To the rear! Seal the slit flap!”

They had a metal shutter designed to reduce visibility and fragments. It wasn’t built for this, but it was all they had. Two men wrestled it down, hands slipping with sweat.

The stream outside ceased, then returned again in short bursts, probing, searching, as if the tank operator were looking for the bunker’s weakest argument.

Sato’s ears rang.

Hori, pale, said, “Captain… we can’t—”

Sato grabbed him by the shoulder, hard enough to steady him. “Listen to me,” Sato said, voice low and fierce. “This bunker is not a tomb. It is a tool. We move if it becomes unusable.”

Morita coughed, eyes watering. “Exit tunnel?” he rasped.

Sato nodded. “Now.”

They had built an escape crawl space leading to a concealed opening uphill, meant for withdrawal or reposition. It was narrow, damp, and humiliating, but it existed for exactly one reason: survival.

Sato waved his men toward it.

One by one, they crawled into the tunnel, dragging ammunition, pulling the wounded, moving like desperate insects through darkness. The bunker behind them shook slightly as the tank’s stream struck again, and the air in the tunnel felt suddenly precious.

Sato crawled last, refusing to leave until he was sure the others were moving.

As he pushed into the tunnel, he heard the bunker’s interior lantern shatter.

Then the world behind him became a roaring hiss.

Not an explosion.

Something worse: the sound of air being forced to surrender.

Sato crawled faster.

He emerged from the concealed uphill opening into brush and gray daylight that smelled of smoke and crushed leaves. He rolled to the side, dragging Hori with him.

They lay there, panting, listening.

Below, the Sherman moved slowly past the bunker’s face as American infantry advanced around it. The tank didn’t even linger long. It didn’t need to. It had done its work—forced the bunker to abandon its role, turned a “fixed” position into a liability.

Sato stared, heart pounding, and felt a bitter clarity settle over him.

This wasn’t just a tank.

It was a doctrine on tracks.

A doctrine that said: You can hide from shells. You can resist bullets. But you cannot argue with a machine that turns your shelter into a trap.

By afternoon, the bunker line had begun to unravel.

Not everywhere. Not all at once. But in a pattern that felt inevitable: the flame tank advanced with infantry, pauses of probing fire, sudden focused bursts of heat against suspected positions, then infantry flowing forward once resistance weakened or withdrew.

Some bunkers held longer, their crews refusing to abandon them. Others evacuated through tunnels and trenches, only to be caught by advancing infantry or pinned by supporting fire. The defensive line, designed to be a maze, was being converted into a series of isolated rooms—each one sealed off and dealt with.

General Akiyama watched reports pile up like stones.

“Position 12—silent.”

“Position 14—withdrawn.”

“Position 9—no response.”

“Enemy armor advancing steadily, infantry close support.”

Akiyama’s jaw tightened until it ached. He had built a system that punished the enemy for approaching. Now the enemy had brought a tool that punished staying.

Ishikawa returned, sweat-darkened, eyes sharp with fatigue.

“Sir,” Ishikawa said, “our anti-tank teams cannot close. Their infantry screen is too disciplined. And the tank does not rush; it pauses, it waits, it uses its device only when it is confident.”

Akiyama stared at the map again. His neat geometry now looked like a child’s drawing compared to the enemy’s methodical pressure.

“They called it a slow beast,” Akiyama murmured, almost to himself.

Ishikawa swallowed. “Yes, sir.”

Akiyama’s voice turned flat. “Slow is not weakness if nothing can stop you.”

Ishikawa said nothing.

Akiyama stood and walked to the entrance of the command post. Outside, the air was thick with haze. He could hear distant engines—steady, patient. He could also hear scattered rifle fire, the frantic sound of a line losing its shape.

For a moment, Akiyama imagined the Sherman as a creature: not fast, not elegant, but unstoppable, with a mouth that made concrete feel temporary.

He hated the thought.

He hated even more that it fit.

Akiyama returned to the table and picked up his pencil. He drew new lines—fallback points, new pockets, a reorganization that might hold for a few more hours, maybe a day.

But as he drew, he realized something that made his hand hesitate:

His bunker line had been designed around endurance—hold, resist, bleed the enemy.

The flame tank attacked endurance itself. It didn’t just knock on a door. It made the room behind the door unlivable.

Akiyama set the pencil down and felt, for the first time in months, a kind of helpless anger that had nowhere to go.

At dusk, Sato and the remnants of his bunker crew gathered in a shallow gully with other survivors—men from Positions 11, 13, and 15. Faces were streaked with soot and sweat. Eyes darted constantly, as if the tank might roll out of the dark itself.

Hori sat beside Sato, trembling slightly.

“They didn’t even stop,” Hori whispered. “They didn’t even celebrate. They just… moved on.”

Sato nodded. “That’s why it worked.”

A young lieutenant from another position—Lieutenant Nakamura—spoke bitterly. “We built bunkers to last. We thought time was our ally.”

Sato looked up at the dimming sky. “Time is always someone’s ally,” he said. “Today it was theirs.”

Nakamura’s voice cracked. “How do you fight that thing?”

Sato didn’t answer immediately, because the honest answer was ugly.

You fought it by catching it alone. By forcing it into a mine lane. By stripping its infantry screen. By being lucky. By being willing to lose men in close approaches that might or might not succeed.

And even then, Sato wasn’t sure.

He finally said, “You don’t fight it the way you want to. You fight it the way it forces you to.”

Hori swallowed. “So… we were wrong to laugh.”

Sato gave a tired exhale. “Laughing was never the mistake,” he said. “Believing laughter was armor—that was the mistake.”

The gully fell quiet.

Far away, an engine idled, then moved again, a low grinding that seemed to promise the same lesson tomorrow.

Sato took out his notebook and wrote another private line beneath the first:

“We built a maze. They brought a torch.”

He stared at it, then closed the notebook.

Around him, men checked weapons, redistributed ammunition, whispered to the wounded. They were trying to rebuild a line out of fragments.

Sato knew they might succeed for an hour, perhaps. A day, if the island offered a lucky ridge.

But he also knew this:

The slow beast had changed the meaning of “safe” on the battlefield. It had turned the bunker—once a symbol of stubborn endurance—into a place where endurance could become suffocation.

Sato looked into the dark and tried to imagine a future where engineers could answer this with an invention of their own.

But war rarely waited for inventors.

It only waited for engines.

And somewhere out there, under a dim sky, the heavy tracks kept moving—patient, methodical—toward the next bunker mouth that would learn, too late, that steel didn’t need to be fast to be final.

News

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany, the stunned reaction inside German High…

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat into his first major triumph, the shockwaves reached Rommel himself—forcing a private…

The Day the Numbers Broke the Silence

When Patton’s forces stunned the world by capturing 50,000 enemy troops in a single day, the furious reaction from the…

The Sniper Who Questioned Everything

A skilled German sniper expects only hostility when cornered by Allied soldiers—but instead receives unexpected mercy, sparking a profound journey…

The Night Watchman’s Most Puzzling Case

A determined military policeman spends weeks hunting the elusive bread thief plaguing the camp—only to discover a shocking, hilarious, and…

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

End of content

No more pages to load