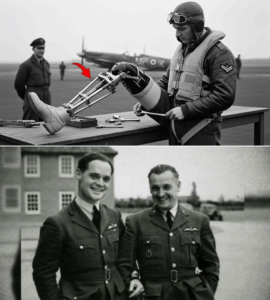

They Mocked the “Legless Pilot” as a Joke of the Skies, Until His Twin Metal Legs Gripped the Rudder Pedals and He Sent Twenty-One Enemy Fighters Spiraling Down in Flames

The first time Daniel “Danny” Cole heard someone call him “the legless pilot,” he laughed harder than anyone.

He was twenty-three, fresh from training, visiting an elementary school near his base to talk about flying. A little boy in the front row, all freckles and courage, had blurted it out without thinking.

“If you crash, will they call you the legless pilot?”

The room went silent. Teachers stiffened. A few kids gasped.

Danny just grinned.

“If I crash,” he said, “they’ll call me late for dinner. But if I don’t, you can call me anything you like—as long as it’s ‘sir’ when I’m in uniform.”

The class erupted in giggles. The tension broke. And the nickname, tossed out like a stone in a pond, sank without a ripple.

Back then, the idea that he could ever lose his legs felt as ridiculous as the idea that he could lose his wings.

Back then, war was still mostly a headline, not a shadow.

The Night Everything Changed

Three years later, on a rain-slick night in early spring, the sky above the training field was black and unforgiving.

Danny’s Hurricane trainer hit the runway hard, bounced, and skidded sideways. The crosswind slapped the plane like a hand. Instruments blurred. The runway lights vanished in a sheet of rain.

“Easy, easy…” he muttered, wrestling the stick.

He never saw the drainage ditch.

There was just the violent wrench of metal, the scream of tearing aluminum, the sharp smell of fuel, and a pain that didn’t feel real until his world went white.

The next thing he knew, he was upside down, hanging from his harness, his legs pinned under twisted metal.

“Cole! Hold on!” someone shouted, distorted, far away.

He looked down and saw—only for a second—where the cockpit had crumpled, the way the footwell had folded like paper. He saw his right leg at a wrong angle, his left leg trapped between jagged edges.

He didn’t remember screaming. Maybe he did. Maybe the roaring in his ears drowned it out.

Then there was fire.

Fuel dripped, caught, and the world became an orange blur.

“Get him out! Now!”

Hands fought the buckles. A knife flashed. Someone pulled him backward, dragging him across wet ground, away from heat that felt like the surface of the sun.

He passed out staring at the underside of another plane, its belly calm and intact against the rain-streaked sky.

When he woke in the hospital, the smell of antiseptic replaced the smell of burning fuel.

He tried to move his legs.

Nothing happened.

At first, he figured the drugs were strong or the bandages were tight. His mind, stubborn and optimistic, filled in the blanks.

“You’re all right, Cole,” he told himself. “Small break. A few weeks. You’ll be back in the cockpit.”

Then he saw the look on the nurse’s face when she came to check his IV. Her eyes dropped, then snapped back up. Her smile was forced.

“Morning, Lieutenant,” she said.

“Morning,” he croaked. “What’s… the damage?”

She hesitated.

“The doctor will explain,” she said softly.

That was when the first cold piece of truth slid between his ribs.

“You Will Never Fly Again”

The doctor was kind, which almost made it worse.

“Lieutenant Cole,” he began, clipboard in hand, glasses low on his nose, “you were very lucky to survive that crash.”

Danny looked past him to the white sheet that ended halfway down the bed.

“Define ‘lucky,’ Doc.”

The doctor followed his gaze.

Where his legs should have been, the blanket lay flat.

He’d known, somewhere under the morphine and denial. But knowing in the abstract was different from seeing that terrifying emptiness.

“We had to take them both,” the doctor said gently. “There was massive trauma. Infection risk. There was no way to save them.”

Danny stared at the ceiling.

“How high?” he asked, surprised at how steady his voice sounded.

“Above the knee,” the doctor replied. “We’ve fitted you with temporary stumps. When you’ve healed, we’ll talk about artificial limbs. You’ll walk again, with training.”

Danny swallowed. His throat felt raw.

“And flying?” he asked.

The doctor paused. It was the kind of pause that spoke volumes.

“Son,” he said at last, “you’ve done your bit. You were a fine pilot. But this… this changes things. Aviation medical standards are strict for a reason. You’ll be discharged with honor. There will be other ways to serve your country.”

“You’re saying I’ll never fly again.”

The doctor hesitated, then nodded.

“I’m sorry.”

For a long time, neither of them spoke.

Outside the ward, a radio played a scratchy big band tune. Nurses moved from bed to bed. Somewhere down the hall, someone laughed too loudly, the nervous laughter of people pretending the world wasn’t on fire.

Inside Danny, something cracked.

Not just grief for his legs. Not just fear of a future where stairs looked like mountains.

It was deeper than that: the shattering of an identity.

He had been a pilot—not just a man who flew planes, but someone who felt more at home in the air than on the ground.

Now the ground had claimed him, quite literally.

He lay there for hours, letting the morphine dull the edges of his thoughts, staring at the place where his body ended and the blank sheet began.

At some point, the door opened again.

A woman’s voice, stern and brisk, cut through the haze.

“So. You’re the one who tried to barbecue himself in a ditch.”

He turned his head.

A tall woman in a neat uniform stood at his bedside, a clipboard under her arm, steel in her eyes. Her hair was pulled back tight, not a strand out of place.

“And you are?” he rasped.

“Margaret Price. Rehabilitation coordinator. If you’re planning to spend the rest of your life staring at that sheet feeling sorry for yourself, I’d like to schedule it properly so we don’t waste everyone’s time.”

Danny blinked.

“Excuse me?”

“You heard me,” she said, unruffled. “You have two choices, Lieutenant: learn a new way to move forward, or let this bed swallow you. I’ve got a waiting list of men outside who’d give anything to have your chance.”

“My chance?” he shot back. “In case you missed it, my legs are…”

“Gone,” she finished for him. “Yes. I can see that. But your hands work. Your eyes work. Your brain works, presumably. You can speak, which I’m starting to regret. That’s more than some.”

Anger flared in his chest.

“You have no idea what it’s like to—”

“To wake up and find your body isn’t what you remember?” she said, leaning in. “To be told you’ll never do what you love again? To hear people lower their voices when they talk about you as if your life is over?”

Her gaze hardned.

“Lieutenant, this ward is full of people whose lives have changed in terrible ways. You’re not special. The only thing that will make you stand out is what you do next.”

The argument grew sharp, voices rising, eyes flashing. Around them, nurses glanced over, ready to intervene if the shouting got worse.

“Even if I learn to walk,” Danny said through clenched teeth, “I’ll never be a pilot again. That’s what I am. That’s all I am.”

“Well then,” she replied, unfazed, “it’s time you became more.”

They stared at each other, the air between them charged.

Finally, she straightened.

“Your artificial limbs will be ready to fit in a few months,” she said crisply. “When they are, I expect you to be ready to use them. I’ll be back.”

She walked out, heels clicking, leaving Danny more furious—and more awake—than he’d been since the crash.

He didn’t know it yet, but that argument, raw and uncomfortable, would matter as much as any dogfight he ever flew.

Because it lit a fuse.

Learning to Walk on Metal

Rehab was pain, repetition, and humiliation all wrapped together.

The first day they brought in the artificial legs, they looked like something from a science fiction magazine: hollow metal tubes, leather straps, hinges where knees should be.

“Lightweight,” the technician said. “Strong. We’ll adjust them as you go.”

“Do they come with instructions?” Danny muttered.

Margaret was there, arms crossed.

“Put them on,” she said. “We’ll worry about graceful later. Today we just don’t fall on our face.”

The first time he stood, he felt like a puppet whose strings were being yanked by an unskilled hand. The floor seemed too far away, the room too tall.

Sweat ran down his back.

“Don’t lock your hips,” Margaret instructed. “Let the weight settle. The legs are tools, not anchors. Own them.”

He took one step.

Then another.

Then his right artificial foot caught on the linoleum, and he pitched forward.

He braced for impact that never came.

A firm hand grabbed his arm, another his shoulder.

“I’ve got you,” Margaret said quietly. “Now try again.”

Days turned into weeks. The parallel bars became his battlefield. Standing, stepping, turning, falling, getting back up.

Other men in the rehab ward watched. Some scowled, wrapped in their own pain. Some whispered encouragement.

“Look at Cole,” one said. “Walking on tin stilts.”

“Legless pilot,” another joked, not unkindly. “Maybe they’ll bolt those things to the rudder.”

The nickname came back, this time from peers, and hit different. It stung, but also sparked.

Late one afternoon, drenched in sweat, Danny gripped the bars and stared at his reflection in the mirror: a young man, thinner than before, pale but not broken, standing on metal legs that gleamed in the fluorescent light.

“This isn’t the end,” he told his reflection. “Not if I don’t let it be.”

He didn’t know how or when, but a thought had begun to form in the back of his mind, stubborn as a weed:

If I can walk, I can sit.

If I can sit, I can fly.

Who says you need flesh and bone in your calves to work a rudder pedal?

The Impossible Request

Six months after the crash, walking on his artificial legs with a cane, Danny requested a meeting with the base medical board.

The clerk reading his file nearly choked.

“You want what?” he asked.

“My flight status reinstated,” Danny said calmly.

The clerk stared at the line on the form.

Applicant requests reconsideration of flying status, with artificial limbs.

“You know this is crazy, right?” the clerk said. “They’ve never approved anything like this.”

“Then I’ll be the first.”

The clerk shook his head, but stamped the form.

“It’s your funeral,” he muttered.

The medical board room felt like a courtroom: long table, three officers in white coats, a pile of papers thicker than a phone book.

The chairman, a stern colonel with a mustache that looked like it had survived two previous wars, flipped through the file.

“Lieutenant Cole,” he began, “you are requesting reinstatement to active flying duty despite bilateral above-knee amputations. Is that correct?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You understand why the regulations exist.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Care to explain why we should make an exception?”

Danny took a breath.

“Because I can still do the job,” he said. “Flying is more about hands, eyes, and judgment than it is about shins. I can work rudder and brakes with these.” He tapped his metal legs. “We can modify the cockpit if needed. I’m not asking for special treatment. I’m asking for a fair test.”

The colonel raised an eyebrow.

“A fair test,” he repeated. “And if you fail?”

“Then I’ll hang up my flight jacket and find another way to serve. But I want to know it’s because I can’t, not because someone assumed.”

One of the other doctors, a younger major, leaned forward.

“Walking with prosthetics is one thing,” he said. “Operating a fighter under combat stress is another. What if you lose a leg in turbulence? What if a strap breaks? What if you have to bail out?”

“I’ll tie them on extra tight, sir,” Danny said lightly. Then, more seriously: “I know the risks. I crashed once. I survived. I accept that I may not be so lucky next time. But every pilot accepts that, legs or no legs.”

A tense silence settled.

The colonel and the younger doctors exchanged glances. The argument was becoming heated—not in volume, but in stakes.

“You’re asking us to put our names on something that could get you killed,” the major said quietly. “If you die because we bent the rules, we live with that.”

“And if you ground me because it’s easier,” Danny shot back, “I live with this for the rest of my life, knowing I walked away from a fight I could have joined.”

Their eyes locked. For a moment, it felt like the rehab argument with Margaret all over again—only now the cost of losing was much higher.

Finally, the third doctor, an older man with tired eyes, spoke up.

“Let him try,” he said. “With an instructor, in a trainer, under controlled conditions. If he crashes, we’ll be there. If he doesn’t… we might learn something.”

The colonel frowned.

“This could set a precedent,” he warned.

“Yes, sir,” the older doctor said. “A precedent for not writing off everyone who doesn’t fit our idea of ‘perfect.’”

The colonel sighed.

“Very well,” he said at last. “Lieutenant Cole, you will undergo a series of evaluation flights under supervision. This is not approval for combat duty. It is simply a test. Understood?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Don’t make me regret this,” the colonel added.

“I’ll do my best, sir,” Danny replied, heart pounding.

Back in the Air

The first time he climbed into a cockpit again, it was like coming home and sneaking in through the window.

The trainer sat on the tarmac, sunlight gleaming off its wings. An instructor waited in the rear seat, head poking out above the canopy.

“You sure about this, Cole?” he called. “I draw the line at carrying you if you fall.”

“I’ve got my legs on,” Danny joked. “What more do you want?”

He climbed the small ladder carefully, metal feet clanking on the rungs. The ground crew watched, a mix of curiosity and disbelief on their faces.

Once in the cockpit, he did something that surprised even him: he smiled.

The familiar smell of fuel, oil, and worn leather wrapped around him like an old jacket. The instrument panel, all dials and needles, looked like the face of an old friend.

He strapped in, then pulled the special harness down to secure his thighs and prosthetic legs firmly against the seat. He’d worked with mechanics for weeks to modify the rudder pedals and brakes, adding brackets and straps that his metal feet could hook into.

“Feet on pedals?” the instructor asked through the intercom.

“Feet on pedals,” Danny confirmed, flexing his hips. The pedals moved. The rudder twitched. It wasn’t as smooth as before, but it was possible.

“Hands on stick, eyes on horizon. Let’s see what you’ve got.”

The engine roared to life. The plane vibrated, eager.

As they taxied, Danny worked the brakes carefully. It felt clumsy at first, the feedback different through metal than through flesh. But he adapted quickly, his brain mapping the new sensations.

“Takeoff is yours,” the instructor said. “I’m on the controls with you.”

They lined up. The runway stretched ahead, a strip of possibility.

“Throttle up,” Danny murmured.

The plane surged forward. His metal legs braced, his hips working the rudder to keep them straight. At the right moment, he eased back on the stick.

The ground fell away.

He was flying.

He laughed out loud, the sound half joy, half disbelief.

They climbed into a wide blue sky. Clouds drifted below, harmless cotton instead of the hard obstacles they’d seemed from a hospital bed.

“Level off at five thousand,” the instructor said. “Let’s try some turns.”

Left turns, right turns, climbs, descents. The controls responded smoothly. His feet found their new rhythm. The artificial knees didn’t care about gravity; they only cared about his intent.

After an hour, the instructor spoke.

“I’m going to let go of the controls,” he said. “You’ve got it.”

Danny flew for another ten minutes on his own, hands and metal legs working as if they’d always been a team.

When they landed, the approach wasn’t perfect, but it was safe. The wheels chirped on the runway. They rolled to a stop.

On the ground, the instructor climbed out and looked up at him.

“Well?” Danny asked.

The instructor chewed his lip, then nodded slowly.

“You can fly,” he said. “You’re rough in spots, but you can fly.”

Word spread quickly.

The “legless pilot” who’d broken himself in a ditch was back in the sky.

Some called him reckless. Others called him an inspiration.

The Germans, of course, knew nothing about him yet.

But they would.

Laughter in the Enemy Briefing Room

On the other side of the channel, in a smoky briefing room, a German squadron studied intelligence photos of new Allied pilots.

They laughed when they saw the one of Danny.

“Look at this,” a young lieutenant said, smirking. “They’re so desperate, they’re sending up cripples now.”

In the grainy image, Danny stood beside his plane, leaning lightly on a cane, metal gleaming where his trouser legs ended.

“They call him ‘the legless pilot,’ apparently,” the intelligence officer said, flipping through his notes.

More laughter.

“Maybe we should shoot at his feet,” someone joked.

“Just aim low, you’ll miss him entirely,” another added.

The room filled with smug chuckles. The idea of a man with metal legs in a cockpit seemed like a bad joke, a sign of Allied weakness.

No one in that room considered that having already lost his legs, this pilot might be less afraid of anything else they could take.

No one imagined that this “joke” would soon carve their unit’s emblem into his tally board, one fiery spiral at a time.

Into Combat

Approval for full combat status didn’t come overnight.

Danny’s evaluation flights turned into more advanced tests: formation flying, gunnery practice, simulated emergencies.

He forced himself to be ruthlessly honest.

If he found a maneuver he couldn’t manage smoothly with his prosthetics, he drilled it ten, twenty, thirty times. If a strap slipped, he redesigned it with the ground crew. If a landing went sideways, he replayed it in his head until he understood every mistake.

He wasn’t satisfied with being “almost as good as before.” He wanted to be better. Sharper. More disciplined.

The war didn’t pause for his rehabilitation.

By the time he transferred to a frontline fighter squadron, the skies over Europe were thick with contrails and stories.

The first day he rolled his metal legs into the ready room, conversation died.

Pilots glanced up from their coffee and cards.

Some stared.

Some looked away, uncomfortable.

The squadron commander, Major Collins, stood, his face a controlled neutral.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “this is Lieutenant Daniel Cole. He’s joining our merry band.”

A murmur rolled through the room.

Collins continued.

“He’s already logged more flight hours than most of you. His medical clearance is signed by people who outrank all of us. His legs are none of your business unless he kicks you with them.”

A few polite chuckles.

“Any questions?”

One pilot, younger than Danny, raised a hand hesitantly.

“Sir… can he, uh… can he bail out?” he asked.

Danny answered himself.

“If I have to,” he said, “I’ll figure it out on the way down.”

The room laughed, this time with him, not at him.

The ice cracked a little.

Collins tossed him a squadron patch.

“Don’t make me regret this, Cole,” he said quietly.

“I’ll do my best, sir,” Danny replied.

The first time he took off in formation, the other pilots watched him like hawks.

He slid into position smoothly, his plane moving as if guided by instinct.

On his first combat mission, over gray water and green fields, they met a small enemy patrol. Two planes downed, no losses.

Not spectacular. But solid.

He didn’t see the enemy pilot’s face as his rounds stitched across the fuselage. He didn’t want to. They were just shapes trying to kill his friends.

In that first dogfight, something shifted.

He wasn’t “the legless pilot” anymore, not in the minds behind those guns. He was just another Allied fighter, dangerous and determined.

Back in the debrief, the intelligence officer mentioned something that made Danny’s jaw tighten.

“Radio chatter from the other side referred to ‘that cripple plane,’” he said. “Looks like they’ve noticed your legs, Cole.”

The room waited for Danny’s reaction.

He shrugged.

“Then they know where I’ve already been hurt,” he said. “Maybe they’ll waste time aiming at the wrong place.”

Smiles spread around the room.

The joke diffused the tension.

But inside Danny, another fuse lit.

If they were laughing, they didn’t understand yet.

He would change that.

Twenty-One Fighters

History doesn’t record every heartbeat, every bead of sweat, every half-second decision that leads to a tally mark on the side of a plane.

It remembers the numbers.

Three enemy fighters downed on his fifth mission.

Two more on his eighth.

A shared kill here, a probable there.

The day he shot down his tenth, his squadron painted a small emblem under his cockpit: a black silhouette with twelve tiny lines beneath it to mark aerial victories and damaged enemy planes.

“Double ace soon,” someone said.

He waved them off.

“Some of those are just ‘maybes,’” he replied. “The only ones that count are the ones that don’t come back to try again.”

But at night, alone, he’d run his fingers lightly over the marks.

Not out of pride for destruction, but out of grim relief—for every fighter he dropped, a bomber might make it home, a ground crew might not get strafed, a village might not be hit.

On his fifteenth victory, his metal legs locked against the rudder, keeping the slip just right as he lined up behind an enemy fighter trying to escape into cloud.

On his seventeenth, he fought through a vertigo-inducing corkscrew with an enemy pilot who clearly had no intention of going down without taking someone with him.

On his nineteenth, his plane came back with holes in the wings and a chunk missing from the tail, his right metal leg numb where a piece of shrapnel had pinged off it.

“How’s the leg?” the crew chief asked.

Danny looked down at the dented metal.

“Better than the last pair,” he said dryly. “We’ll buff it out.”

By the time he reached twenty-one fighters destroyed—confirmed kills, logged, cross-checked, signed off by intelligence—the nickname “legless pilot” had traveled farther than he had ever imagined.

In Allied circles, it became a story of stubborn courage.

In enemy mess halls, it was a bitter joke.

“You hear about that pilot with no legs?” someone would ask over thin soup.

“Yes,” another would reply, jaw tight. “He shot down my cousin.”

The laughter had stopped.

The Fight That Almost Took Everything

Victory number twenty-one didn’t come easy.

It happened over a patchwork of fields and roads in enemy territory, on a morning that started like any other.

The squadron had launched to escort bombers. The sky was hazy, sun struggling through high clouds. Everything looked washed out, like an old photograph.

“Bandits, eleven o’clock high,” came the call over the radio.

Enemy fighters dove in, sunlight flashing on their wings.

The first minutes were chaos: planes twisting, diving, climbing, tracers sewing the air.

Danny’s world narrowed to a circle framed by his canopy and the crosshairs of his gunsight.

He caught one enemy crossing his path, rolled, and fired in a short controlled burst. Hits on the wing root. The plane shuddered, then peeled away, smoke trailing.

“Good hit, Six,” his wingman called.

“One,” Danny acknowledged, already looking for the next.

He saw a bomber under attack, a fighter crawling up its blind spot.

He dove, metal legs clamped hard, body straining under G-force.

“Hold on, boys,” he muttered.

His rounds struck the enemy just as it started firing. The fighter snapped sideways, wing disintegrating. The bomber lurched but kept going.

That was two.

Then he made a mistake.

He followed a third enemy too deep, too far from his own formation, trusting his instincts and the Merlin’s power to keep him safe.

For a few glorious seconds, it worked.

He latched onto the enemy’s tail, matched its every move, and fired. Tracers walked up the fuselage. The plane burst into flames, rolling over, the pilot bailing out too late.

“Three,” he said, adrenaline surging.

Then tracers whipped past his canopy from nowhere.

He’d forgotten the obvious: in the sky, you were never alone.

“Check six!” his wingman screamed.

He rolled hard, but too late. Bullets stitched his right wing, ripped through the fuselage. The plane shuddered.

Warning lights flickered. The Merlin coughed, then steadied, wounded but alive.

Something slammed into his right artificial leg, twisting it.

His foot slipped off the rudder pedal.

For a terrifying second, he lost control. The plane yawed wildly, the horizon spinning.

“Not like this,” he growled.

He kicked his hips, struggling to slam the metal foot back into place. The modified strap had torn. The leg dangled uselessly, flopping with every motion.

With only his left leg locked in, his right side wanted to wander. The plane skidded in every turn, fighting him.

He could bail out. He could call it done, hope the chute worked, hope he landed somewhere that wouldn’t shoot him on sight.

But he was in enemy territory, low on options, and he could still hear bomber engines thundering somewhere above.

He thought of the medical board’s doubts, of Margaret’s fierce eyes, of the German briefing room laughter he’d never heard but could easily imagine.

He thought of twenty-one enemy fighters that would happily have killed him if given the chance.

“No,” he snarled to nobody. “Not today.”

He loosened his grip on the stick just slightly, letting the plane tell him what it wanted to do, fighting less, guiding more.

He used more aileron and elevator, less rudder, flying “sloppy” by the book but effective enough to keep him in the air. He compensated for the yaw with tiny adjustments, reading the ball on the turn-and-bank indicator like a lifeline.

Behind him, the enemy fighter that had hit him swept past, overshooting in its eagerness.

The German pilot, seeing the smoke from Danny’s wing, probably thought he’d finished him. Maybe he lined up another shot, expecting an easy kill.

He didn’t expect the “cripple” to snap into a diving turn that looked like a controlled fall.

Danny’s stomach dropped. His left leg burned with strain. His right artificial leg flailed, dead weight. But his hands were calm, precise.

He looped under his attacker, pulled up, and came around behind him.

The German pilot, surprised, rolled and dived for the deck, trying to escape.

With one working pedal and a lot of stubbornness, Danny followed.

At treetop height, they danced a deadly waltz: banking, jinking, streaking over roads and fields so low that cows scattered.

The Merlin engine roared, wounded but unyielding.

Danny waited.

No rush. No panic.

When the enemy finally made the mistake he’d been waiting for—a slightly too-wide turn, a burst of tracers in the wrong direction—Danny was there.

He squeezed the trigger.

The enemy fighter shuddered. Smoke blossomed from its engine. It rolled over, clipped a line of trees, and exploded in a field.

“Four,” he whispered, though he knew the official tally from that fight would likely be three, not four. Someone else had a claim on the first.

His own plane was bleeding. Fuel gauge dropping. Control sluggish.

“Cole, get out of there!” Collins’ voice snapped over the radio. “You’re hit bad.”

“On my way,” Danny replied, the understatement of the year.

He coaxed the damaged plane towards friendly territory, every mile a negotiation between gravity and will.

The landing, when it came, wasn’t pretty. He barely made the field. The right wing scraped the ground; the plane slewed sideways and came to a shuddering stop in a spray of dirt.

Ground crew ran toward him.

He shut down the engine, flipped the canopy, and laughed shakily.

One of the crew stared at his right leg.

The metal shin had a neat bullet hole through it, the polished surface twisted where the impact had bent it.

“Huh,” Danny said, staring. “Good thing those weren’t original equipment.”

They hauled him out, more gently than last time.

He limped on his one fully attached leg and one mangled prosthetic back to the briefing room, refusing a stretcher. Pain flared with every step, but he relished it.

He was walking.

He’d landed.

He’d brought the plane and himself home.

The squadron crowded around as he recounted the fight.

When the intelligence officer confirmed three more enemy fighters destroyed—bringing his total to twenty-one—someone let out a low whistle.

“Twenty-one,” Collins said. “For a man who was supposed to never fly again.”

Danny shrugged.

“I guess nobody told the enemy that,” he said.

What the Laughter Missed

When the war finally ended, numbers were tallied.

Pilots with all their limbs and pilots with artificial ones went home with medals, scars, nightmares.

Danny Cole’s record—twenty-one enemy fighters destroyed, dozens more damaged, countless missions flown—became part of the history books. Some got his numbers wrong. Some embellished. Some forgot.

People loved the headline version of his story:

“Legless pilot becomes ace.”

It was neat. Clean. Almost cute, in a twisted way.

What the headline missed was everything in between: the pain, the rehab arguments, the medical board tension, the endless hours in the cockpit relearning how to move.

It missed the subtle truth that courage isn’t the absence of fear or pain, but the decision to move anyway.

Years later, a young pilot, standing in front of a trainer, would ask him:

“How did you do it, sir? How did you fly and fight with metal legs?”

Danny would tilt his head, thinking.

“I didn’t fly with metal legs,” he’d say. “I flew with hands, eyes, and a brain that refused to accept someone else’s idea of my limits. The legs were just… hardware.”

“And the Germans?” the young pilot would ask. “Is it true they laughed at you?”

“Oh, probably,” Danny would say with a half-smile. “People laugh at what they don’t understand. That’s their problem. The thing about laughter from the ground is, it gets very quiet when you’re above it.”

He’d look out the window at the sky.

“They learned,” he’d add softly. “Not because I wanted revenge, but because every fighter I brought down meant someone else got to live. That’s all war flying is, in the end. Buying time for someone you’ll never meet.”

The story of the “legless pilot” isn’t really about legs, or even about planes.

It’s about what happens when a person who’s been told “you will never” decides to answer, calmly and persistently, “watch me.”

It’s about an argument in a hospital room that turned serious and tense and refused to end in pity.

It’s about a medical board that bent just enough to let reality, not fear, decide.

It’s about enemies who laughed, then stopped laughing when the tally climbed and the rumors spread.

And it’s about the simple, stubborn truth that resilience doesn’t always look like movie heroics. Sometimes it looks like a man strapping on cold metal limbs at dawn, walking to a waiting fighter, and climbing in, one rung at a time.

Germans laughed at the “legless pilot” once.

History remembers something else:

The sound of twenty-one enemy fighters falling silent while he stayed in the air.

News

THE NEWS THAT DETONATED ACROSS THE MEDIA WORLD

Two Rival Late-Night Legends Stun America by Secretly Launching an Unfiltered Independent News Channel — But Insider Leaks About the…

A PODCAST EPISODE NO ONE WAS READY FOR

A Celebrity Host Stuns a Political Power Couple Live On-Air — Refusing to Let Their “Mysterious, Too-Quiet Husband” Near His…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced a Secretive Independent Newsroom — But Their Tease of a Hidden…

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,” and Accidentally Exposed the Truth About Our Family in Front of Everyone

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,”…

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He Never Expected the Entire Reception to Hear My Response and Watch Our Family Finally Break Open”

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He…

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting Match Broke Out, and the Truth About Their Relationship Forced Our Family to Choose Sides

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting…

End of content

No more pages to load