They Laughed When the Stranded Mechanic Said He’d Build a Cannon From Junked Aircraft — Until His Homemade Gun Turned a Lonely Pacific Airstrip Into a 12-Minute Ambush That Left 20 Japanese Attackers Down

By the time Claire found the strange gun, the museum was almost empty.

Late sun came through the high windows of the small aviation hall, turning dust motes into slow-moving stars. Old propellers hung from the ceiling. A rusted radial engine sat on a stand with a polite little sign: PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH, EVEN IF IT LOOKS LIKE IT WANTS A HUG.

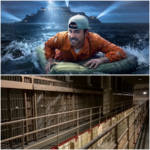

But the thing in the corner didn’t look like anything in the books.

It was… wrong.

Not in a bad way, just in the way of something that had been born out of desperation instead of design. A long barrel — aircraft style, with cooling holes — bolted onto a Frankenstein carriage made from landing gear struts, bits of wing spar, and what looked suspiciously like a seat frame.

The placard in front of it said:

IMPROVISED 20mm GUN CARRIAGE

Constructed from wrecked aircraft parts, 1944

Used by Sgt. Daniel “Dan” Mercer to defend Taki Atoll airstrip

Attribution: 20 confirmed enemy casualties in single engagement

Claire blinked.

“Twenty?” she murmured. “With… that?”

She’d grown up on stories of World War II — her great-grandfather had been in Europe — but they’d always been about big things. Big bombers. Big fleets. Big battles with names like thunder.

This… this looked like something a bored teenager would weld together in a garage because he’d lost a bet.

“Ugly little thing, isn’t she?” a voice said behind her.

Claire turned.

The man standing there was in his late eighties by the look of him, his posture straight despite the cane in his hand. He wore a simple polo shirt and a baseball cap with a faded emblem: a winged propeller.

On the cap, in small, gold letters, it said:

USAAF

Taki Atoll

1944–45

Claire glanced from the cap to the gun, then back at him.

“You knew the guy who built this?” she asked.

The old man smiled a little, the kind of smile that had more history than humor.

“Knew him,” he said. “Argued with him. Thought he was out of his mind. Then watched him prove me wrong.”

He stepped closer to the cobbled-together weapon, resting one hand gently on the carriage like he was greeting an old friend.

“Name’s Walt,” he said. “Sergeant Walter Hayes, 5th Air Force. And that crazy contraption over there? That’s Dan Mercer’s gun.”

“Dan Mercer,” Claire said, reading the placard again. “You were there? When he…?” She hesitated. “When that ‘single engagement’ happened?”

Walt’s eyes went distant for a moment, as if the museum walls had been replaced by something else.

“Yeah,” he said quietly. “I was there. And let me tell you something, young lady — the Japanese weren’t the only ones who couldn’t believe what he’d built. I didn’t believe it would work either, not for a second. And I told him so.”

He chuckled once, a dry little sound.

“That argument?” he said. “It got serious. It got loud. And if we hadn’t been stuck on a hot little island in the middle of nowhere, I’d have walked away and let him play with his scrap. Good thing I didn’t.”

Claire shifted her backpack on her shoulder and tilted her head.

“Will you tell me?” she asked. “The whole story? Not the museum version. The real one.”

Walt looked at her for a moment, weighing her like a pilot weighing a cargo load.

“You got a few minutes?” he asked.

“I’ve got as long as you’ve got,” she said.

Walt nodded, eyes going back to the mismatched metal in front of them.

“All right then,” he said. “Let’s go back to Taki.”

The island had been a dot on the map and a rumor in the barracks long before they landed on it.

Taki Atoll. Somewhere west of nowhere, an oval of coral and sand with a strip of jungle and a single runway scratched into its spine. It was supposed to be a waystation — a place to refuel small aircraft, to stash supplies, to squat and listen with radio sets for whispers of the wider war.

When the C-47 dropped them off in May 1944, the heat hit Walt like a hand.

“It’s like walking into a soup kitchen,” he’d muttered, half to himself, stepping down onto the pierced-steel planking of the makeshift airstrip. Humidity wrapped around him, thick and salty, carrying the smell of aviation fuel, damp earth, and something sweet rotting in the trees.

“Quit whining, Hayes,” the sergeant behind him grunted, lugging a crate of spare parts. “You wanted to get away from the stateside motor pool, you got your wish. Welcome to paradise.”

Paradise, as it turned out, consisted of:

One short runway, lined with a mix of rough-hewn timber and steel matting.

Three ragged tents that called themselves the maintenance depot.

A radio shack made from sandbags and prayers.

And a handful of men who looked at the new arrivals like someone had just delivered them extra work.

The ranking officer on the island was Captain James “Jim” Rourke — lean, sunburned, with engine grease permanently under his nails and a cigarette hanging off his lip like it had been welded there.

He met Walt and his team by the nose of a battered P-40 that had clearly seen better days and worse landings.

“You Hayes?” Rourke asked.

“Yes, sir,” Walt said, snapping a salute.

Rourke flicked ashes into the sand and looked him up and down.

“Mechanic?” he asked.

“Aircraft mechanic, yes sir,” Walt said. “Engines, hydraulics, whatever you need.”

“Good,” Rourke said. “We need everything. That bird over there won’t start, the one behind it starts but won’t stop, and the third one is missing half its right wing because our last pilot thought coral makes a good brake.”

He jerked a thumb toward the ocean.

“Japan’s that way,” he said. “They’d like this island back. We’d like them not to have it. That make sense to you?”

“Yes, sir,” Walt said.

“Good,” Rourke said again. “You keep my planes flying; my pilots keep you from having to learn Japanese the hard way.”

He started to turn away, then paused, as if remembering something.

“Oh,” he added, “and we’ve got one more stray they dropped on us. Some kind of engineering genius from the Air Service. Don’t let him talk you into anything that sounds fun.”

Walt frowned.

“Fun, sir?” he asked.

Rourke’s smile crooked sideways.

“You’ll see,” he said. “Name’s Mercer. Sergeant Dan Mercer. You’ll know him when you hear the most ridiculous idea you’ve ever heard in your life. He’ll be the one talking.”

Walt met Dan Mercer two days later, half-under the wing of a wrecked light bomber that had made it almost to the strip before deciding it would rather be scrap.

The bomber’s fuselage sat crookedly at the edge of the airfield, nose buried in a sand dune, tail up like a dog digging for a bone. The impact had twisted its frame and snapped both wings, leaving the guts of the plane’s systems exposed.

Inside those guts, a man in a sweat-soaked undershirt was happily taking things apart.

“Uh,” Walt said, shading his eyes. “You’re Mercer?”

The man slid out from under the wing and sat up.

He was in his late twenties, with dark hair flattened under a cap, a face that had probably been handsome before too much sun and too little sleep, and eyes that were just a little too bright.

“Depends,” he said. “You here to yell at me for stealing parts from your precious hangar stock, or you here to help me change the balance of power on this rock?”

Walt stared.

“I… brought a wrench?” he said, holding up the tool.

Mercer grinned.

“Good enough,” he said, climbing to his feet and wiping his hands on a rag that was doing nothing for his shirt.

“Dan Mercer,” he said, offering a hand. “Twelve years a mechanic, four years a glider pilot, now exiled to this fine vacation spot because someone back at command decided I had too many ideas.”

“Walter Hayes,” Walt said, shaking his hand. “And from the look of things, you haven’t run out of ideas yet.”

Mercer gestured at the bomber’s carcass.

“Look at this beauty,” he said. “Crashed her on the delivery flight. Pilot walked away. Aircraft didn’t. That right there—” he patted a protruding section of barrel “—is a twenty-millimeter aircraft cannon. They bolt them under wings and in noses to chew up anything stupid enough to fly in front of them.”

Walt squinted.

“I’ve seen them,” he said. “We work around them at the base. What are you doing with it?”

“Liberating it,” Mercer said. “From the tyranny of gravity.”

Walt blinked.

“Gravity?” he repeated.

“Yeah,” Mercer said. “Up there, she’s only dangerous when someone flies her into something. Down here?” He smiled in a way that made Walt feel like he was standing too close to a lightning storm. “Down here, we can use her however we like.”

He dropped back to one knee and tugged at a bolt.

“Help me get this loose,” he said. “Then I’ll show you a magic trick.”

The argument started when Rourke found out what they were doing.

By then, the twenty-millimeter gun was no longer attached to the wrecked bomber. It sat on the ground, a long, sleek barrel with a boxy breech, surrounded by a scattering of tools, metal brackets, and what looked suspiciously like the remains of a landing gear strut.

Walt held the cannon steady while Mercer measured distances, muttering under his breath.

“If we brace it here… and anchor the recoil to this… maybe add a third point of contact so it doesn’t kick itself into the trees…”

Rourke’s shadow fell across them.

“Mercer,” he said. “Why is there a perfectly good cannon lying on my airstrip instead of on an airplane?”

Mercer glanced up.

“Because, sir,” he said, “the airplane is no longer perfectly good. The cannon, on the other hand, works just fine, and I thought we might as well make use of it.”

Rourke folded his arms.

“And how exactly,” he asked, “do you plan to make use of a twenty-millimeter cannon sitting on sand?”

Mercer’s eyes lit up.

“That,” he said, “is the best part.”

He pointed at the pile of scavenged aircraft parts.

“We build a carriage,” he said. “A frame. Something that can take the recoil and let us aim it. We take the ammunition we’ve already got in the depot — plenty of belts sitting around waiting for planes that may never get here — and we turn this into a proper ground gun. Something that can chew up barges trying to land on our beach, or trucks if they come down the strip, or…”

He spread his hands, seeing it already.

“Sir, imagine a Japanese officer deciding to get clever and mass his men on that road we’ve got on the other side of the island,” Mercer said. “He’s thinking we’ll have nothing heavier than rifles and a couple of machine guns. And suddenly—”

He mimed pulling a trigger.

“Surprise.”

Rourke’s expression didn’t change much, but the lines around his mouth deepened.

“You know what this sounds like to me, Mercer?” he asked.

“A stroke of genius?” Mercer suggested.

“A court-martial waiting to happen,” Rourke said. “We are not a field artillery outfit. We are not authorized to take apart crashed planes for fun. And we are absolutely not authorized to build our own weapons out of scrap.”

Mercer stood, brushing sand from his knees.

“With respect, sir,” he said, and Walt winced — those were always dangerous words — “that crashed bomber has been sitting there for three weeks. No one’s coming to recover it. The cannons on it will rust where they are. The ammo we’ve got in the shack is just taking up space. The enemy is out there, somewhere, thinking about how to get this island back. We can either give them a warm welcome, or we can wave politely and hope they send a small party.”

Rourke’s jaw tightened.

“And what happens,” he asked, “when your homemade contraption blows up? Or jams? Or tips over and kills a man because you don’t understand how much recoil a twenty-millimeter puts out without a plane wrapped around it?”

Mercer’s mouth opened. Walt saw him getting ready to say something clever, something that would make Rourke’s blood pressure spike.

He stepped in.

“Sir,” Walt said quickly. “If I may?”

Rourke shifted his attention.

“Hayes,” he said. “You’re involved in this madness too?”

Walt shifted his wrench from one hand to the other.

“I’ve been helping him,” Walt admitted. “And watching what he’s doing. He’s not as crazy as he sounds. We can brace the frame with struts from the landing gear. Use parts from the wing spars as supports. Bolt the whole thing into the coral at the edge of the tree line to take the kick. The math checks out.”

Rourke snorted.

“Oh, good,” he said dryly. “The math checks out. I feel better already.”

He stepped closer to the cannon, tapping it with the toe of his boot.

“You really think you can make this thing work?” he asked Mercer.

“I know I can,” Mercer said. “And if I’m wrong, worst case, we’ve wasted some spare parts and I get a bruised shoulder. Best case, we have a gun on this island that no one on the other side expects, and that might make the difference between holding this strip and losing it.”

The silence stretched.

In the distance, a gull shrieked. Somewhere in the jungle, a bird answered.

Rourke looked from the cannon to Mercer to Walt, then out toward the blue line of the ocean.

“All right,” he said finally. “You’ve got forty-eight hours. You do this on your own time, without pulling my other men off essential jobs. You build it strong enough that it doesn’t kill anyone when you test it. You get Hayes here to sign off on the mechanics. And if I hear one word about you ‘borrowing’ vital parts, I will personally throw that thing into the lagoon and you after it. Understood?”

Mercer snapped to a salute.

“Yes, sir,” he said, grinning.

Rourke shook his head.

“You’re out of your mind,” he muttered as he walked away.

“That’s not a no,” Mercer called after him.

Walt watched Rourke go, then turned back to Mercer.

“You know,” he said, “you really are out of your mind.”

Mercer clapped him on the shoulder.

“Maybe,” he said. “But if I’m right, Hayes, you’re going to be very glad you backed the crazy guy.”

Walt sighed.

“Forty-eight hours,” he said. “Let’s make sure we don’t blow ourselves up in the process.”

They worked in shifts, stealing time between regular maintenance jobs.

By day, Walt crawled over tired fighters, changing filters, patching bullet holes, coaxing grumbling engines back to life. By night, under a sky full of stars bigger than any he’d seen back home, he and Mercer wrestled with metal.

The gun carriage slowly took shape — a triangular frame built from landing gear struts, cross-braced with cut sections of wing spar. The twenty-millimeter cannon sat in a cradle of steel brackets that used to be part of the bomber’s internal skeleton. A salvaged aircraft seat frame became a kind of aiming bench, with a cut-down control column welded on as a traverse handle.

“You know this looks insane, right?” Walt said at one point, wiping sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand as he watched Mercer weld.

Mercer lifted his goggles, leaving raccoon rings of clean skin around his eyes.

“In what way?” he asked.

“In every way,” Walt said. “If my mother could see me helping you build this, she’d ship herself to this island just to drag me home by my ear.”

Mercer laughed.

“Your mother’s welcome to visit,” he said. “We could use someone to yell at the coconuts.”

The argument flared again on the second night, when Mercer suggested where to put the gun.

“I want it on the tree line overlooking the lagoon,” he said, poking at a rough sketch in the sand. “Good field of fire along the beach. If they try to land boats, we’ll have a clear shot.”

Walt shook his head.

“And if they come down the road from the other side of the island?” he asked. “We’ll have built ourselves a very fancy beach ornament while they march up behind us.”

“We can’t cover everything,” Mercer said. “We pick the most likely approach.”

“And how do you know it’s the lagoon?” Walt shot back. “You moonlight as a Japanese planner now?”

Mercer’s jaw clenched.

“Look at the charts,” he said. “The lagoon’s deep enough for their landing craft. The far side is all coral teeth. If I were them—”

“You’re not them,” Walt snapped. “You’re a mechanic with a welding habit.”

The words hung there, sharper than he’d meant them to be.

Mercer’s face shuttered.

“You don’t have to help,” he said.

Walt exhaled, forcing his shoulders to relax.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “It’s just… if this thing actually works, we get one good surprise. One. Maybe two. I don’t want to waste it pointing at the wrong patch of water.”

Mercer studied him, then the sketch, then the map tacked up in the maintenance tent.

The narrow road that cut across the island from lagoon to wild side was little more than packed coral and dirt, but it was there. A straight line. A tempting line.

“If they drop troops on the far side,” Walt said, tracing the road with a finger, “they can rush the strip before we know they’re coming. No landing craft to spot. Just a column of men and trucks.”

Mercer tapped the middle of the road.

“Here,” he said. “This bend. Hedgerows on both sides. Little rise here where the coral banks up. If we put the gun here, sink the legs into the bank, we’ve got a perfect ambush spot. Cover from both sides. They come around that corner thinking it’s just jungle, and bam.”

He mimed the recoil again.

Walt nodded slowly.

“That’s better,” he said. “If we can get it there without breaking our backs.”

Mercer’s grin returned, sharper now.

“We’ll get it there,” he said. “We’ve got forty-eight hours, remember? That’s a lifetime.”

Walt snorted.

“In this war?” he said. “That’s about twelve minutes.”

The test fire nearly ended the whole project.

They dragged the finished carriage — gun mounted, bolts torqued, braces welded — to the edge of the jungle near the strip and dug its legs into the coral. Mercer checked every connection twice. Walt checked them three times.

“This is a bad idea,” Walt muttered as he fed the first belt of twenty-millimeter rounds into the gun. Fat brass casings gleamed in the sun, each one a little promise of havoc.

“Which part?” Mercer asked.

“The part where we’re standing directly behind a weapon the size of a tree trunk that was never meant to sit on the ground,” Walt said. “Or the part where, if it jumps, it jumps straight into us.”

Mercer patted the metal.

“She won’t jump,” he said. “Not with these braces. The aircraft took most of the recoil before. We’re giving it a new airframe.”

“That’s what worries me,” Walt said. “This ‘airframe’ doesn’t fly.”

Mercer settled behind the improvised seat, one eye to the little gunsight he’d salvaged from the bomber. His hands wrapped around the control stick, which now traversed the gun left and right.

“Ready,” he said.

“Captain Rourke wanted to be here,” Walt reminded him.

“He wanted to be informed,” Mercer said. “He did not specify whether ‘before’ or ‘after.’”

“You’re playing with the captain’s patience,” Walt said.

“I’m playing with our lives,” Mercer replied. “Big difference.”

He took a breath.

“Clear!” he shouted.

The men from the maintenance crew, who’d come to watch from a safe distance, ducked behind a pile of sandbags.

Mercer squeezed the trigger.

The cannon barked. The sound was sharper than a tank gun, more like someone had slammed a giant metal door. The recoil slammed into the carriage, pushing it back a fraction of an inch. The braces held. Dust puffed from the coral.

On the far side of the test range, an old fifty-five gallon drum leapt as the shell hit it, the impact sending a spray of rust and dirt into the air.

Mercer laughed, half-wild.

“Did you see that?” he yelled. “She works!”

Walt’s heart, which had been lodged somewhere near his throat, slid back into his chest.

“You’re insane,” he said. “But I’ll be damned — it works.”

He looked at the gun, then at the men peering cautiously from behind the sandbags.

One of them, a skinny radio operator named Felix, stepped forward.

“If the captain finds out we fired this thing without him, he’ll string us up,” Felix said.

Mercer waved a hand.

“I’ll tell him we were just… cleaning it,” he said.

Felix snorted.

“Yeah,” he said. “Good luck with that.”

The argument that night in the mess tent was louder than the test fire.

Rourke stood with his hands on his hips, jaw clenched so tight Walt could see the muscle jumping.

“You fired it,” he said. “Without me. Without armorers. Without proper range markers. Without a medic on standby.”

“We had Felix,” Mercer said. “He knows where the bandaids are.”

“Mercer,” Rourke snarled.

“Yes, sir,” Mercer said, lips twitching.

“You are a menace,” Rourke said. “If we weren’t short-handed, I’d ship you back to headquarters gift-wrapped. As it is—” He exhaled. “As it is, that damn thing might be useful. Which is the only reason I don’t have you digging latrines until Christmas.”

Mercer’s grin softened.

“So we can keep it?” he asked.

Rourke pinched the bridge of his nose.

“Put it where you want it,” he said. “Camouflage it. Don’t tell half the island about it. And for heaven’s sake, don’t get any ideas about naming it after yourself.”

“I was thinking ‘Rourke’s Folly,’ actually,” Mercer murmured.

“What was that?” Rourke snapped.

“Nothing, sir,” Mercer said quickly.

The men in the tent tried very hard not to laugh. The argument had been serious, had been tense, had come close to exploding into something that would have sent Mercer packing. But in the end, the gun stayed.

It waited, quiet and ugly, at the bend in the coral road.

The Japanese came ten days later.

They came at dawn, when the sky was a pale, bruised blue and the air already felt like a damp blanket.

The alert hit the island in three jolts:

First, the faint thump of distant gunfire from the far side of the atoll.

Second, the telephone in the radio shack jangling like someone was trying to shake the whole building down.

Third, Felix bursting into the maintenance tent, eyes wide.

“Boats on the wild side,” he gasped. “They’ve landed a company, maybe more. Rourke wants all nonessential personnel to the inner line. They’re coming down the road.”

Walt’s stomach dropped.

The road.

He sprinted out of the tent, boots slipping on the damp crushed coral, and nearly collided with Mercer, who was already running.

“They’re here,” Mercer panted.

“No kidding,” Walt said. “Where’s Rourke?”

“Forward line,” Mercer said. “He’s got the rifle squad and the two machine guns covering the entrance to the strip. He told us to stay back.”

Walt grabbed his arm.

“Stay back?” he snapped. “From what? The picnic?”

Mercer’s eyes burned.

“From the ambush,” he said. “Our ambush. Come on.”

They ran.

The jungle on either side of the road was thick, but the path itself was clear enough — a hard-packed coral track with hedges of low trees and brush on either side. The bend where they’d emplaced the gun was about halfway between beach and strip. As they approached, Walt could hear the distant, rhythmic crack of small arms, the occasional deeper thump of a mortar.

They scrambled up the slight rise and ducked behind the screen of leaves that hid the gun emplacement.

Felix and another man were already there, crouched low.

“About time,” Felix hissed. “We heard them on the radio. They’re moving fast.”

Mercer dropped into the seat behind the gun, hands finding the controls like they’d been molded there.

“Walt,” he said. “Check the belts.”

Walt swung into position beside him, fingers running over the ammunition belt feeding into the gun. The metal links were smooth with wear, the cartridges heavy.

“Two full belts loaded,” he said. “Another two ready.”

Felix crawled up beside them with a field telephone.

“I’ve got a line back to Rourke,” Felix said. “He says hold fire until we see the whites of their… well. You know.”

“When we see their buttons,” Mercer said. “Got it.”

They waited.

The sounds from the far side of the island grew clearer. Shouts in a language Walt had only heard in training films. The occasional burst of automatic fire. The distant crack of a rifle answered by two more.

Walt’s mouth was dry. He swallowed and tasted dust and fear.

“Maybe they won’t come this way,” Felix whispered.

“Maybe they’ll get bored and go home,” Walt whispered back. “Maybe this whole war is just a very expensive misunderstanding. Maybe—”

“Shh,” Mercer said sharply.

He heard it first.

Boots.

Lots of them. The steady, synchronized thump of feet hitting coral. The swish of cloth. The metallic clink of gear.

Walt pressed his back against the coral bank, peering through a gap in the leaves.

The column appeared around the bend like a scene from one of those training films come to life.

Japanese infantry. Dozens of them, maybe more. Helmets with canvas covers, rifles slung, bayonets glinting. A few light machine guns on tripods carried between men. Behind them, a small truck, bouncing on the rough road, loaded with ammunition and boxes of who-knew-what.

They were moving at a confident, purposeful pace — not running, not creeping, just… advancing. They’d clearly encountered resistance on the beach, maybe skirmished with Rourke’s forward scouts. But here, in the shadow of the hedgerows, they looked relaxed.

They thought they were just on a walk.

Mercer leaned into the gun sight, exhaling slowly.

“Range, Hayes?” he asked softly.

Walt did the quick mental math.

“Seventy yards,” he whispered. “Eighty max. You can’t miss.”

“Everyone can miss,” Mercer murmured. “That’s the problem.”

Felix pressed the field phone handset to his ear.

“They’re in the lane,” he whispered. “Right where we expected. Yeah. Yeah, he’s on the gun. No, I’m not yelling at him. You come up here and yell at him if you want.”

A pause, then: “Rourke says fire when ready.”

Mercer’s jaw clenched.

“Ready,” he said.

The first Japanese officer in the column — at least, Walt assumed he was an officer from the way he held himself — turned his head toward the bend in the road, perhaps catching a flicker of movement.

His mouth opened.

Mercer squeezed the trigger.

The twenty-millimeter cannon roared.

The first shell hit the road in front of the leading group and detonated, sending a spray of coral fragments and shrapnel into the packed ranks. Walt saw men jerk, stumble, go down.

Mercer adjusted a fraction, fired again.

This time the shell hit the front axle of the truck, exploding in a bright flash. The vehicle’s front wheels disintegrated, the truck slamming nose-first into the road. Boxes flew. The driver pitched forward, arms flung up.

The column convulsed.

Shouts, startled, panicked.

Some of the soldiers dove for the ditches on either side of the road, scrambling for cover. Others flattened themselves against the bank that, unfortunately for them, concealed the gun.

“Walk it back,” Walt heard himself say, voice strangely calm. “Short bursts. Don’t waste rounds.”

Mercer did.

He fired in quick, controlled shots, the gun bucking under his hands. Each shell ripped into the tightly packed road — bodies, gear, earth. Men cried out and tried to crawl. Others dragged their wounded comrades toward the ditch, not yet sure where the fire was coming from.

A light machine gun team tried to set up their weapon in the open. Mercer’s third shell took them before they could pull the trigger.

Felix flinched with each blast.

“Oh my God,” he whispered. “Oh my God.”

Walt’s stomach felt like it had turned to ice, but his hands were steady as he checked the belt.

“Halfway through the first belt,” he said. “Keep going.”

Down the road, one of the Japanese soldiers finally spotted the muzzle flash at the hedgerow.

He shouted, pointing. A few men turned and fired their rifles blindly into the trees.

Bullets snapped overhead, punching into leaves and branches. Splinters showered down.

“Guess we’re invited to the party now,” Mercer muttered.

He shifted his aim, sending a burst toward the ditch where the pointing soldier had been. The fire from that spot faltered.

The argument Walt and Mercer had had in the tent a week before — about where to put the gun, about whether it would do any good — seemed absurdly distant now.

This was what it was for.

The Japanese column, caught in the open, tried to adapt.

A squad broke off and rushed the bank, hugging the inside of the bend, trying to get into grenade range.

“Here they come,” Walt said.

Mercer’s jaw muscle jumped.

“I see them,” he said.

He depressed the barrel a little and fired a short burst straight into the road in front of the rushing men. The shells chewed up coral and cloth and boots. The charge dissolved in a tangle of bodies and dropped rifles.

“Mercer!” Felix shouted over the noise. “Rourke says keep them off the strip at all costs! You’re buying us time!”

Mercer didn’t answer. He didn’t have breath to spare.

The cannon barked and barked. The carriage shuddered. Smoke curled from the breech. Walt fed a new belt into the feed tray, fingers moving automatically.

He found himself counting without meaning to.

Seven, eight, nine men down. Twelve. Fifteen.

None of it felt real.

The Japanese soldiers were no longer a neat column. They were a scattered, desperate mass, some clinging to the ditch, some trying to fire back through the undergrowth, some dragging the wounded, some crawling.

A few broke and ran back the way they’d come, heads down, rifles forgotten.

“Second belt,” Walt said. “We’re into the second belt.”

Mercer’s shoulder throbbed from the recoil, but he barely registered it.

He fired at the truck again, making sure it stayed a burning obstacle. He put shells into the back ranks, where men had bunched up in confusion. He took out the tripod of another machine gun before its crew could steady it.

The gun jammed once, the bolt sticking half-open.

Walt’s heart lurched.

“Jam!” he barked.

Mercer eased his finger off the trigger.

“Cover me,” he said, even though there was nothing Walt could do against an entire company but throw harsh language.

He yanked the charging handle back, cleared the misfed round with a practiced flick, slammed the bolt forward.

“Up!” he shouted.

Walt felt a bubble of wild laughter rise in his chest.

“This is insane,” he said.

“Keep feeding, Hayes,” Mercer said through gritted teeth. “We can panic when we’re dead.”

Felix ducked as a bullet smacked into the coral bank above his head, showering him with chips.

“They’re trying to flank!” Felix yelled. “Some of them are slipping into the jungle!”

“Of course they are,” Walt said. “They’re not stupid. They’re just surprised.”

He risked a glance over the bank.

Yes. A small group had indeed abandoned the road and melted into the foliage, working their way around. It would take them a few minutes to get behind the gun position — minutes Rourke needed at the strip to set up his own defenses.

Mercer fired again, raking the road one last time.

The volume of return fire had dropped significantly. A few stray shots cracked, but the concentrated hail from earlier was gone.

Walt’s mental count hovered somewhere around twenty.

“Mercer,” he said quietly. “That’s enough. We’ve done what we can.”

Mercer kept his eye to the sight, breathing hard.

“Another burst,” he said. “Make sure they don’t regroup.”

He fired.

The last few shells in the belt clanged through the gun, punching holes in abandoned packs and already-shattered coral. A man in the ditch who’d started to rise dropped back down, movement stilled.

Then the breech slammed open on an empty feed.

“Dry,” Walt said. “Two belts left in reserve — but if they’re in the trees already…”

Mercer sat back slowly, shoulders trembling.

“Yeah,” he said. “You’re right. Time to go.”

Felix grabbed the field phone.

“Rourke says fall back now,” he said. “He’s got his line set up. Says you bought him more time than he dared hope for.”

Mercer wiped sweat from his face with the back of his hand.

“Let’s not waste it,” he said.

They broke down the position as quickly as they dared, hauling the remaining ammunition away, camouflaging the gun as best they could. The carriage was too heavy to move in a hurry; they dragged it a few feet back from the embankment, covered it with branches and a canvas tarp.

“Think they’ll find it?” Felix asked as they scrambled down the back slope toward the strip.

“Maybe,” Mercer said. “But by then we’ll either be holding the line or swimming.”

They ran.

Behind them, the road was a chaos of smoke and dust and bodies.

The fight at the strip was shorter and messier.

Rourke had his men dug in behind hastily erected barricades — oil drums, sandbags, anything they could throw between themselves and incoming fire. The Japanese survivors from the ambush, reinforced by whatever units had landed elsewhere, hit the defenses with grim determination.

Walt’s memories of that second fight were scattered flashes: the hot sting of a graze along his arm, the stink of cordite, the taste of fear sour in his mouth. The sight of Rourke standing upright for a second too long to throw a grenade, then ducking down as if some invisible hand had yanked his head by the collar.

At some point, they heard the distant drone of aircraft engines overhead — friendly this time. P-38s, sleek and deadly, swooping down to rake the beach and the jungle where the landing force had staged. The fight at the strip sputtered, then broke.

By mid-morning, the surviving Japanese troops were either dead, captured, or retreating back toward their boats.

By noon, the island looked like a storm had rolled over it and changed its mind.

By evening, Walt sat on an ammo crate near the gun emplacement, watching the sky turn red, the cannon beside him now quiet and ugly again.

Mercer lowered himself onto the crate next to him with a groan.

“Shoulder?” Walt asked.

“Shoulder,” Mercer said, rotating the joint carefully. “Feels like I’ve been punching a wall for an hour.”

Walt let out a breath.

“How many do you think?” he asked.

Mercer’s eyes were tired.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Too many. More than I thought I’d ever… more than I wanted.”

Walt nodded.

“They were soldiers,” he said. “Same as us. They’d have done the same to Rourke and the others if they’d reached the strip.”

“I know,” Mercer said. “Doesn’t make counting them any easier.”

He looked at the gun carriage, at the scorch marks on the coral road beyond.

“When I started building this thing, I thought about numbers,” he said. “How much armor a twenty-millimeter can punch. How many rounds per minute. How far the recoil would push it. It was all math and metal.”

He scratched at a streak of dried sweat on his arm.

“Turns out the hardest number is the one they’ll put on the report,” he said. “Twenty, maybe. Maybe more. Maybe less. ‘Enemy casualties.’ As if that makes it simple.”

Walt nudged his shoulder gently.

“If it helps,” he said, “Rourke says you’re a lunatic. But a useful one. He’s talking about recommending you for a medal.”

Mercer snorted.

“Let him give it to the gun,” he said. “She’s the one who did the work.”

The official report said:

On 18 May 1944, Sgt. Daniel Mercer, using an improvised 20mm cannon carriage constructed from aircraft parts, engaged an enemy column advancing along the central road of Taki Atoll.

His actions resulted in an estimated 20 enemy casualties and delayed the enemy’s advance, allowing defensive positions at the airstrip to be fully manned.

For his ingenuity and bravery under fire, Sgt. Mercer is hereby awarded the Silver Star.

The Japanese report, captured later, was shorter and more bitter:

Our men encountered unexpected heavy automatic fire from concealed position along the road.

Weapon believed to be aircraft cannon adapted for ground use.

Many brave soldiers fell.

They did not understand, in that report, how a single mechanic on a forgotten island had taken their assumptions about what could and could not be done and turned them inside out.

They did not know about the argument in the mess tent, the late-night welding, the math scribbled in the sand.

They just knew, painfully, that whatever had been waiting behind that bend had teeth.

In the museum, decades later, Walt’s voice grew quiet.

“We didn’t like to talk about the number,” he said. “Not back then. Not later. Twenty sounds like a score in a game. It wasn’t a game.”

Claire nodded, throat tight.

“Do you… regret it?” she asked carefully.

Walt considered.

“I regret the war,” he said. “I regret that any of us had to be in a position where building a gun out of junk was the best idea on the table. I regret that those men on the road didn’t get to grow old and grumble about their joints and tell stories to their grandkids.”

He put his hand on the cool metal of the carriage.

“But I don’t regret this,” he said. “Not this. We were defending an island we’d been told mattered. We were keeping our own people alive. If Mercer hadn’t built this thing, if we hadn’t manned it that morning… I don’t know how that day would have ended. I just know more names would be on more stones.”

Claire looked at the plaques again, at the dates, at the tidy summary of something that had been anything but tidy.

“What happened to Mercer?” she asked.

Walt smiled faintly.

“He went home,” he said. “Eventually. Got his medal in a ceremony so short he almost missed it because he was tinkering with a generator in the back. Married a girl from Kansas. Opened a garage. Spent the rest of his life fixing things instead of breaking them.”

He chuckled.

“I visited him once,” Walt said. “Years after the war. He had an old car up on blocks, engine half out, parts all over the floor. I told him it looked familiar.”

“What did he say?” Claire asked.

“He said, ‘This time, if it blows up, the worst that happens is I owe someone a new fender,’” Walt replied.

They stood in silence for a moment.

Visitors wandered past, glancing at the gun, some barely slowing. A few read the placard, frowned, and moved on. To them, it was just another curiosity in a room full of history.

To Walt, it was twelve minutes in which math and metal and fear and fury had collided on a coral road and changed the shape of a day.

“To the Japanese, it must have looked impossible,” Claire said softly. “A gun where no gun should be.”

Walt nodded.

“They’d been told we were predictable,” he said. “That we’d fight a certain way, with certain tools. Mercer proved them wrong. That’s the thing about war — the side that surprises the story the other side is telling wins more often than not.”

He straightened slowly, leaning on his cane.

“Anyway,” he said, the moment of reminiscence folding gently closed, “enough of an old man’s rambling. You probably came here to see the pretty planes, not the ugly gun.”

Claire shook her head.

“I came here to understand,” she said. “This helps.”

She looked at the carriage one more time, at the mismatched strata of metal.

“You know,” she added, “they really should add your name to the card. ‘Sgt. Mercer and Sgt. Hayes.’ It sounds right.”

Walt laughed.

“Nah,” he said. “I was just the guy feeding the belts and yelling at him not to get himself killed. Mercer was the crazy one. Give him the headline.”

He tapped the plaque lightly.

“The museum people like big numbers,” he said. “Me? I like the small ones.”

“What do you mean?” Claire asked.

“Daily tally,” Walt said. “How many mornings I managed to wake up on that island and still find all my friends breathing. Those were the numbers that mattered.”

He started walking slowly toward the exit.

“Come on,” he said. “I’ll show you the P-38s. Now there’s a plane that was beautiful and deadly on purpose, not by accident.”

Claire took one last look at the improvised gun.

Somewhere, she imagined, a younger version of Walt crouched behind it, heart hammering, feeding belts to a man who refused to accept what the world said couldn’t be done — who took broken pieces of one kind of war and turned them into a shield for another.

The gun sat in its corner, quiet now, its jagged metal edges dulled by time and fingerprints and careful cleaning.

It didn’t look like much.

But once, on a hot morning on a forgotten island, it had changed a story.

That was worth remembering.

News

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of Us Were Ready To Face

The Week My Wife Ran Away With Her Secret Lover And Returned To A Life In Ruins That Neither Of…

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That Turned Our Perfect Life into a Carefully Staged Lie

I Thought My Marriage Was Unbreakable Until a Chance Encounter with My Wife’s Best Friend Exposed the One Secret That…

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point Exposed the Secret Life I Refused to See

My Wife Said She Was Done Being a Wife and Told Me to Deal With It, but Her Breaking Point…

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked Her Best Friend on a Date, and the Truth Behind Her Declaration Finally Came Out

At the Neighborhood BBQ My Wife Announced We Were in an “Open Marriage,” Leaving Everyone Stunned — So I Asked…

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic in Both Their Voices Sent Me Into a Night That Uncovered a Truth I Never Expected

When My Wife Called Me at 2 A.M., I Heard a Man Whisper in the Background — and the Panic…

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages, Everyone in the Elite Restaurant Learned a Lesson They Would Never Forget

The Arrogant Billionaire Mocked the Waitress for Having “No Education,” But When She Calmly Answered Him in Four Different Languages,…

End of content

No more pages to load