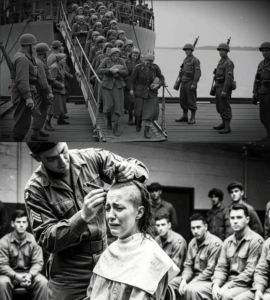

They Endured Lice in Captivity for Eighteen Months, Cherishing Their Hair as the Last Shred of Pride They Owned—Until American Guards Ordered “Delousing,” Switched on the Clippers, and Sparked a Furious Fight over Humiliation, Health, and Who Got to Decide

When they told them to sit down, nobody understood.

It was a warm morning in late August, the kind that made the camp’s dust rise in lazy spirals and cling to sweat-damp skin. The sky over the wire was a sharp, clear blue that made the barracks roofs look even more tired.

“Blocks Three and Four, out!” the interpreter shouted in German. “Line up by the wash house! Bring your combs!”

At first, Lotte laughed.

“Combs?” she said, tying her hair tighter under her scarf as she stepped out into the yard. “What will they do, inspect our braids for treason?”

“It’s about the lice,” Klara muttered beside her. “Has to be.”

They had all heard the rumors. Another women’s camp, deeper in Germany, ravaged by lice and typhus. A transport arriving in France with half its prisoners scratching themselves bloody. Medical officers complaining to the Americans that “the German women are crawling.”

“We’ve had lice for eighteen months,” Greta said grimly as they took their place at the end of the line outside the wash house. “Suddenly it’s urgent?”

“It’s urgent when disease threatens them,” Klara replied. “Up till then, we are just itchy inventory.”

The line moved slowly. A few women came out of the wash house and hurried back toward the barracks, heads wrapped in towels. None of them met anyone’s eyes.

“That’s not a good sign,” Klara murmured.

Lotte’s stomach tightened.

She reached under her scarf and scratched behind her ear, feeling the familiar small bites, the raised lines. They had delousing powder, sometimes. They boiled clothes when they could. But there was never enough hot water, enough soap, enough anything.

Her scalp had been alive for months. They all had stories: lice on the trains, lice in the barns, lice on the hospital ward when she’d nursed wounded boys under broken windows.

“Maybe they finally got enough powder,” she said. “The American doctor was furious last week. She said if we didn’t treat it, we’d have a typhus epidemic and the camp would be quarantined.”

Greta folded her arms, fingers gripping her elbows.

“We looked after our hair,” she said. “Even with everything. We braided it. We washed it when we could. We used breadcrumbs for dry shampoo. We do not need them to tell us we are dirty.”

“It isn’t about pride,” Lotte said. “It’s about disease.”

“It’s always about disease with you,” Greta snapped. “You see everything through a nurse’s eyes. You forget that hair is more than… a nest.”

Klara put a hand on her arm.

“You mean it’s your last jewelry,” she said. “We know.”

Greta’s jaw tightened.

“My husband used to say my hair was ‘the last luxury in this miserable world,’” she said. “When the bombs started, when the ration cards shrank, when the sirens blurred into one long sound, he would still run his hand through it and say, ‘At least this is untouched.’”

She glanced at the wash house door.

“If they take that,” she said quietly, “what is left?”

Lotte didn’t have an answer.

The line crept forward.

Inside the wash house, the air hummed with a different energy.

Dr. Emily Carter wiped her forehead with the back of her wrist, the rubber of her glove squeaking against damp skin. The clippers in her hand buzzed, a low threatening sound that vibrated up her arm.

She hated that sound.

“Next,” she said in German.

The woman in the chair flinched.

Her hair, once carefully pinned under a scarf, lay loose around her shoulders, dull and dusty but still visibly cared for. There were braids, a twist at the back, a ribbon someone had managed to salvage from before the war.

Emily parted a section with a comb. Tiny white specks clung to the strands. She could feel them, almost, under her fingers, even through the glove.

“Nissen,” she said, more to herself than the patient. “Lice eggs. Everywhere.”

The woman didn’t respond.

“You’ve had them a long time,” Emily tried again, softer. “How long?”

The woman’s jaw worked.

“Since they moved us from the camp near Kassel,” she said. “Eighteen months.”

Emily’s throat tightened.

“Eighteen…” she repeated. “My God.”

“We tried,” the woman blurted, as if suddenly needing to confess. “We boiled our combs when they let us. We took turns with the powder. But new ones came. On the trains. In the straw. Under the blankets. They never stopped.”

“I know,” Emily said. “It’s not your fault.”

She looked at the clippers in her hand.

She thought of the telegram that had arrived two days ago.

LICE INFESTATION PERSISTENT STOP OUTBREAK TYPHUS IN SECTOR D STOP ALL LONG HAIR MUST BE CUT OR SHAVED WHERE LICE UNCONTROLLABLE STOP NO EXCEPTIONS STOP HEALTH COMMAND

She’d argued. She’d begged for more powder, for more soap, for time.

“You can’t just order us to shave thousands of women,” she’d said to Captain Hayes, voice too loud in his cramped office. “Hair is not just hair to them.”

“It is to typhus,” Hayes had replied. “We lose a few inches of vanity, that’s one thing. We lose a hundred prisoners and half my guard strength to fever because we couldn’t control lice, that’s another.”

Now, as the woman in the chair watched her with eyes like stones, Emily added up the math as she had been forced to do a hundred times in the field hospitals before the invasion.

Disease versus dignity.

She flicked the switch on the clippers.

They buzzed to life.

“Short,” she said in German. “I can cut it short. Not all off. But very short. The lice will have nowhere to hide.”

The woman stared at her.

“They told us,” she said, voice shaking, “that only traitors and whores had their heads shaved.”

Emily’s chest tightened.

This part hadn’t been in the telegram.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly. “Here, it means you will not get sick. That is all.”

The woman’s hands clenched on the arms of the chair.

“Do it,” she whispered, looking away.

Emily raised the clippers.

They could have used scissors, in theory. But scissors wouldn’t get close enough to the scalps crawling with tiny white ovals. Scissors left places for eggs to hide.

The first pass of the clippers through the hair left a track of pale scalp, a little crooked line.

The woman stiffened.

“Tilt your head,” Emily said gently. “Please.”

Locks slid down onto the sheet.

In the doorway, two American guards shifted, uncomfortable.

“This feels wrong,” one muttered in English. “Like somethin’ out of the wrong newsreel.”

“You want typhus?” the other replied under his breath. “You want to spend your leave in a fever tent?”

“No,” the first answered quickly. “I just… thought we were the good guys.”

Emily pretended not to hear.

“Next,” she called, as the woman’s hair fell in uneven clumps.

Outside, the tension in the line had risen like heat off a stove.

The first woman from their block came out of the wash house without her scarf.

At first Lotte wasn’t sure what was wrong.

Then the woman looked up.

Her head was bare.

Not bald—not quite. A soft fuzz of dark hair remained, clinging close to her scalp like moss on stone. But the braids, the length, the shape that had defined her face—gone.

Gasps rippled through the waiting women.

“They shaved you,” breathed Anna, stepping forward. “Mein Gott…”

The woman’s cheeks burned.

“They cut it,” she said. “The doctor—she said it was… necessary.”

Her voice broke on the last word.

She clutched a small cloth bundle to her chest as if it were a baby. Strands of hair stuck out from the edges.

“What is that?” Klara asked gently.

“My hair,” the woman whispered. “They let me keep it. As if that is a kindness.”

She pressed her lips together and hurried toward the barracks, shoulders hunched.

Greta watched her go, jaw tightening.

“This,” she said, “I will not do.”

“Greta,” Lotte said. “You heard about the lice. About the typhus in the other camp. If we don’t—”

“I have had lice for eighteen months,” Greta snapped. “They did not care then. Now suddenly they remember what soap is, and they reach for the clippers.”

“They’re trying to stop an outbreak,” Lotte said. “It is not… personal.”

“It is always personal when someone cuts your hair,” Greta replied. “Ask anyone who left a village as a girl and had it cropped before basic training.”

Klara squeezed Lotte’s arm.

“She has a point,” she murmured. “We were told that shaving was a punishment. Public. For collaborators. For women who slept with the enemy.”

She lowered her voice.

“Here? It’s private. For lice. But inside…” She tapped her temple. “Inside, it’s the same for them.”

A guard near the door shifted, bored, tapping his boot with the end of his rifle.

“Raus, raus,” he said mechanically. “Move up.”

The line moved.

Another woman emerged from the wash house, head newly bare, eyes shining with angry tears.

“Don’t look at me,” she barked in German when someone stared. “Don’t you dare.”

But they did.

They couldn’t help it.

The sight burrowed under their skin like the lice had burrowed under their scalps.

“It’s like they are stripping away our… identity,” Anna whispered. “Fine, we are POWs. Fine, we wear their numbers. But our hair…”

Klara nodded.

“It’s the last thing we owned,” she said.

“It is not theirs to cut,” Greta said.

“Is it the lice’s?” Lotte asked quietly. “Because they seem to think it is.”

Greta glared.

“You would let them do anything as long as they say ‘medical,’” she said.

“I would let them stop us from scratching ourselves to death,” Lotte replied, heat rising in her cheeks. “We are already weak. Disease will finish what hunger started.”

“You think I don’t know that?” Greta shot back. “I saw my neighbor’s boy die of typhus. Skin like wax. Eyes sunk. I scrubbed the sheets with my own hands. I don’t need you to preach hygiene to me. But this…”

She gestured sharply toward the wash house.

“This is punishment wrapped in paper,” she said. “They are saying, ‘You are dirty. We will make you clean by taking what you have left.’”

Lotte swallowed.

“What would you suggest?” she asked. “We’ve had lice for eighteen months. Powder didn’t work. Combs didn’t work. What else is there?”

Greta’s mouth opened, then closed.

“I would suggest,” she said finally, “that if they cared so much, they would have done something before they saw a risk to themselves. That they would have offered us shears and time. A choice. Cuts in our bunks, among ourselves. Not this…” Her voice cracked. “This parade.”

From somewhere ahead, a woman’s voice rose, high and strained.

“You can’t!” she cried. “Please, don’t! I’ll wear a cap—I’ll sleep outside—I’ll—”

The clippers buzzed louder for a moment, then fell silent.

“You hear that?” Anna whispered. “She begged.”

“And they did it anyway,” Greta said.

“Or she’d be next in the fever tent,” Klara said. “Begging for air instead of for hair.”

The line shuffled forward.

“Next,” called the interpreter. “Barrack Four, five at a time!”

Lotte felt her stomach flip.

“That’s us,” Klara said.

Greta planted her feet.

“I will not go,” she said.

The interpreter’s eyes narrowed.

“You’ll go,” he said flatly. “Or they’ll send you to isolation. You want to spend two weeks in a cold hut with no stove and nothing but a bucket?”

Greta lifted her chin.

“If it means keeping my hair,” she said, “yes.”

Lotte stared at her.

“You would risk your health—our health—over this?” she asked.

“Over this?” Greta echoed. “This is not a ribbon. This is not a dress. This is my head.”

Klara sighed.

“Greta,” she said. “You know what will happen if you refuse. They will make an example. They will say, ‘See, even German women must obey.’”

“They say that every day,” Greta replied. “With or without clippers.”

The guard at the door glanced at the interpreter.

“What’s the holdup?” he asked in English.

“She doesn’t want haircut,” the interpreter said. “She thinks it is… humiliation.”

The guard shrugged.

“Ain’t no one loves gettin’ their head shaved,” he said. “But rules are rules. You want lice or you want clippers?”

The interpreter translated, adding his own sharper edge.

“You want to live, or you want to scratch?” he asked Greta.

Greta’s eyes flashed.

“I want to decide,” she said.

The word hung there.

Lotte felt something twist in her chest.

“That ship sailed when we walked through the gate,” Klara muttered.

Greta looked from the wash house door to the fence to the barracks.

All of them lines she had been forced to cross.

She turned to Lotte suddenly.

“You were a nurse,” she said. “Tell me—how many times did you do something to a patient’s body without their consent because you thought it was best?”

Lotte flinched.

“Sometimes,” she admitted. “When they were unconscious. Or delirious. Or in shock. When there was no time.”

“And here?” Greta demanded. “Is there no time? Did typhus arrive on that last truck? Or did a paper arrive on their desk, and they look at us and see… a problem to be solved with clippers?”

Emily would have winced if she’d heard it.

Lotte took a breath.

“There is time,” she said. “To argue. To shout. To delay. Yes. But lice do not wait for paperwork. They lay eggs every day. And we lay our heads on the same pillows.”

“And if they had come to us in the barracks,” Greta said bitterly. “If they had said, ‘We must cut your hair for your health,’ I would have… screamed less. Here, in a line, under their eyes, with guards at the door…”

She looked away, jaw rigid.

“It feels like being stripped,” she said. “Not of hair. Of… who I am.”

The interpreter rolled his eyes.

“You talk too much,” he said. “Move. You’re holding up everyone.”

Greta stood her ground.

Behind her, the other women shifted, irritated, anxious.

“Greta,” Klara said quietly. “If you don’t go, they’ll stop all of us. Or they’ll cut you last, when tempers are worse. Choose your battlefield.”

Greta let out a slow breath.

She looked at the wash house door.

“Fine,” she said at last. “But I will not thank them.”

“No one asked you to,” Lotte said.

They stepped forward.

Inside, the heat hit them like a wall.

Steam curled from the pipes. The air buzzed with the sound of clippers and the low murmur of exhausted voices.

“Clothes off,” instructed a German nurse—Ilse, who had been press ganged into medical duty. “Shirts at least. They’ll check your scalp and your skin. Sit on the bench. Wait your turn.”

Greta stripped off her scarf with jerky movements, fingers snagging on the knot.

Her hair fell down around her shoulders in a dull brown curtain, streaked with gray, tied in a careful knot at the nape of her neck.

Lotte and Klara did the same.

Lotte shook her head, feeling the weight of it for the first time in what felt like years. It brushed her shoulder blades.

“I used to complain it was too thick,” she said.

“Fate was listening,” Klara replied.

Emily glanced up from her current patient as the new group came in.

She saw the tension in their shoulders, the stiffness in their jaws. The hair—braids, buns, loose lengths—was the first thing she noticed, as always.

She set the clippers down for a moment and stepped back.

“I know,” she said in German, raising her voice enough for the room to hear. “You hate this.”

Several women let out sharp laughs.

“You have no idea,” Greta muttered.

Emily met her eyes.

“Actually,” she said quietly, “I do. The army shaved my brother’s head when he joined up. He wrote me that he felt like he lost three years of his life in an hour.”

“That’s not the same,” Greta said sharply.

“No,” Emily agreed. “It isn’t. But I am not doing this because I enjoy it. I’m doing it because I’ve seen men and women die covered in lice. Because I’ve had to cut hair off corpses when it was too late for it to matter.”

She spread her hands.

“If I could save you and your hair,” she said, “I would. I can’t. So I’ll save you.”

Greta’s mouth tightened.

“Easy to say when it’s not your head,” she said.

Emily nodded.

“True,” she said. “Which is why I won’t tell you not to be angry. Be angry at the war. At the lice. At me. Go ahead. But sit down anyway.”

She picked up the clippers again.

“Who’s first?” she asked.

Silence.

Then, unexpectedly, Anna stepped forward.

“I’ll go,” she said, voice thin but steady.

Greta stared at her.

“You?” she said. “Why?”

Anna shrugged.

“It itches,” she said simply. “I’m tired of scratching.”

She sat in the chair.

Ilse draped a sheet around her shoulders.

Anna’s hair was long, a thick dark rope down her back.

Emily swallowed, then set the clippers at the nape of her neck.

She ran them upward.

The buzzing filled the room.

Hair peeled away, revealing a pale strip of scalp.

Anna flinched, then squeezed her eyes shut.

“Keep going,” she whispered.

Emily did.

Locks slid down onto the sheet, onto the floor.

By the time she was done, Anna looked… younger somehow. Softer and more broken at the same time. Her skull seemed too fragile without the frame of hair.

She reached a hand up tentatively, fingers brushing the rough stubble.

“It feels… strange,” she said.

Ilse handed her a small mirror.

Anna stared at her reflection.

“Who are you?” she asked the glass.

Lotte’s own throat burned.

She watched Anna stand, shoulders squared, and walk back to the group.

Someone reached out to touch her head.

“Don’t,” Anna said, swatting the hand away. Then, after a second, she added, “Not yet.”

Greta took a breath.

Her hands shook as she sat in the chair.

“You will be quick,” she said to Emily. “And you will not speak.”

Emily inclined her head.

“Jawohl,” she said. “As you wish.”

She set the clippers to Greta’s hair.

The first pass was the worst.

Greta’s lips trembled, but she did not make a sound.

Locks fell onto the sheet, then the floor, dull brown against the concrete.

Lotte realized she was holding her own braid so tightly her fingers ached.

“Next?” Ilse asked quietly when Greta stood, swaying.

Klara nudged Lotte.

“Go,” she said. “Before you talk yourself out of it.”

Lotte sat.

Emily’s fingers were surprisingly gentle as she parted her hair.

“Deep breath,” Emily said quietly. “It’ll be over faster than you think.”

Lotte inhaled.

As the clippers moved, she watched strands tumble down, the weight lifting from her scalp and piling on her lap.

She felt naked.

Not like those first clumsy fumblings with a boy behind the church years ago, when clothing had been the thing removed.

This was something else.

Something more exposed.

When it was done, she reached up, touching her scalp.

It felt rough and unfamiliar, like someone else’s head.

She swallowed.

“Thank you,” she said to Emily, surprising herself.

“For… not making a speech.”

Emily smiled faintly.

“Too late for that,” she said. “I gave the speech last night. To myself.”

Back in the barracks, the reaction was immediate.

Some women burst into tears the moment they saw their newly shorn friends.

“It’s like the stories,” one sobbed. “The women in Holland. The ones they said… collaborated.”

“Do we look like collaborators?” Greta snapped. “Starving, in these rags? If they wanted to mark us as traitors, they would do it in the square, not behind walls.”

“Everyone knows we are prisoners,” Klara said. “We do not need shaved heads to prove it.”

Anna sat on her bunk, fingers tracing the curve of her skull.

“It itches less,” she said. “That’s something.”

“That is not nothing,” Lotte replied.

She lay back, the rough blanket scratching her newly exposed scalp. Weirdly, it felt… clean.

As clean as anything in the camp could feel, anyway.

“I hate it,” Greta said, sitting heavily on the bunk across from her. “But I admit… it is… lighter.”

“You’ll get used to it,” Klara said. “Hair grows back. So I’ve been told.”

Greta let out a breath that was almost a laugh.

“Maybe,” she said. “If we live that long.”

That night, as the barracks quieted under the thin veil of sleep, small conversations drifted through the dark.

“You look like a boy,” someone teased gently.

“I feel like a newborn chick,” came the reply.

A few bunks over, Lotte heard Anna’s voice whisper.

“Do you think they did it to punish us?” she asked.

“No,” Lotte replied. “I think they did it because it was the fastest way they knew to stop us from scratching open our skulls.”

“Is that better?” Anna asked.

Lotte considered.

“Maybe intent matters less than effect,” she said. “We are humiliated either way. We are also less likely to die of typhus.”

Anna was quiet for a moment.

“I don’t want to forgive them,” she said.

“You don’t have to,” Lotte said. “You just have to wash.”

Anna huffed.

“You and your practicality,” she said. “One day you’ll look back and say, ‘This was the haircut that saved my life.’”

“If I live long enough to worry about haircuts,” Lotte said, “I’ll call that a victory.”

Months later, in autumn, lice became something they spoke of in the past tense.

“We had lice for eighteen months,” Greta would say, running a hand through hair that was finally long enough to curl behind her ear. “Then the Americans shaved our heads, and we didn’t.”

It never became a pleasant memory. But it became… a marker.

Like everything else in that strange, suspended time, it turned from a crisis into a story, then into one of a thousand anecdotes about war that never dislodged the bigger ones but still insisted on their own importance.

Years after the camp was dismantled and the fences came down, Lotte would sit in a small kitchen with her niece and tell the story.

“We were shocked,” she’d say. “We cried. Some of us screamed. We felt stripped.”

Her niece would reach up, touching her own long hair.

“Did it grow back?” the girl would ask, wide-eyed.

“Yes,” Lotte would say. “Hair grows back. Pride takes longer.”

“And the lice?” the girl would ask.

Lotte would smile wryly.

“They did not come back,” she’d say. “At least not on my head.”

Her niece would frown.

“So you’re… grateful?” she’d ask. “To the Americans for shaving you?”

Lotte would shake her head.

“Grateful is not the word,” she’d say. “I am… honest about it. They did something that hurt and helped at the same time. I can’t put it in a box labeled ‘good’ or ‘bad.’”

She’d run a hand through her gray hair.

“I learned,” she’d say, “that sometimes the things done to our bodies are about the people doing them, not about us. Their fears. Their orders. Their memories of other wars. That doesn’t make them right. But it makes them… human.”

Her niece would nod, not fully understanding but sensing that this was important.

“And you?” the girl would ask. “What did you do with that?”

Lotte would think of Greta and Anna and Klara. Of Emily’s tired face. Of the buzzing clippers.

“I decided,” she’d say slowly, “that I would not let anyone, ever again, tell me that my value lay only in what I looked like. Not enemy. Not friend. Not poster. Not mirror.”

She’d smile.

“And I decided,” she’d add, “that if I got lice in peacetime, I would shave my head myself. Before anyone ordered me to.”

Her niece would laugh.

“You’d look funny,” she’d say.

“I looked funny then too,” Lotte would reply. “Funny and alive.”

She would go to bed that night, older, calmer, still scratching sometimes at memories that had long outlived their physical triggers.

In her dreams, the buzz of clippers would merge with the roar of planes, the crackle of fires, the murmur of women in rows. It would never be just a haircut.

But when she woke up and saw her hair on the pillow, she would smile and think, briefly and fiercely, of hygiene and humiliation and the strange, stubborn ability humans had to survive both.

In another town, in another country, Dr. Emily Carter—now Emily Shaw after a marriage that had lasted longer than she ever expected—would listen to a young nurse complain about a patient.

“He yelled at me,” the nurse would say. “Because I shaved his beard before surgery. Said I was stripping him of his dignity.”

Emily would sip her tea.

“Did you explain why?” she’d ask. “About infection? The mask seal?”

“I tried,” the nurse would say. “He didn’t want to hear it.”

Emily would think of a hot room in France, of hair sliding down onto concrete, of angry eyes and silent tears.

She’d think of the order in her hand and the lice on a scalp and the line she’d walked between doing harm and preventing worse.

“You did the right thing,” she’d say to the nurse. “And you still have to live with his anger. That’s part of the job. It doesn’t make you a villain. It doesn’t make him ungrateful. It just means you both had something to lose.”

The nurse would nod, not fully convinced.

“Someday,” Emily would add, “you’ll have your own story about a clippers decision. And you’ll tell someone, ‘We had lice for months. Then we shaved. And I still think about it.’ That’s okay.”

And somewhere, inside, she would thank the younger version of herself who’d picked up the clippers, given the speech, and then shut up and cut.

Not because it had been perfect.

But because it had kept more people in the barracks and fewer in the fever ward.

War left scars that no amount of shaving or washing could remove.

But in that camp, on that August day, under that too-blue sky, a line had been crossed that had nothing to do with fronts.

German women who had once been told their hair was their glory, their duty, their danger, had watched it fall at the hands of an enemy doctor following an order.

They had cried. They had argued. They had scratched less.

Years later, they would look back and say, with the bluntness that came only with time:

“We had lice for eighteen months. Then they shaved our heads. It was awful. It was necessary. It was not simple.”

And if anyone tried to make it simple, they would shake their heads.

Because they knew now that very little in that war ever was.

THE END

News

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany

When Patton shattered the Siegfried Line and became the first to storm into Germany, the stunned reaction inside German High…

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat

After Patton transformed the disastrous Kasserine Pass defeat into his first major triumph, the shockwaves reached Rommel himself—forcing a private…

The Day the Numbers Broke the Silence

When Patton’s forces stunned the world by capturing 50,000 enemy troops in a single day, the furious reaction from the…

The Sniper Who Questioned Everything

A skilled German sniper expects only hostility when cornered by Allied soldiers—but instead receives unexpected mercy, sparking a profound journey…

The Night Watchman’s Most Puzzling Case

A determined military policeman spends weeks hunting the elusive bread thief plaguing the camp—only to discover a shocking, hilarious, and…

The Five Who Chose Humanity

Five British soldiers on a routine patrol stumble upon 177 stranded female German prisoners, triggering a daring rescue mission that…

End of content

No more pages to load