They Called His Hunting Rifle “Useless in Modern War” and Laughed Him Off the Firing Line — But Over One Frozen Winter, This Quiet Farmer Used It to Stop an Entire Soviet Regiment and Become a Reluctant Legend

By the time they tried to take his rifle away, the snow was already stained with footprints and fear.

It had started snowing the night before the first artillery rounds landed. The flakes came big and lazy, drifting down over the dark fir trees, the frozen fields, the scattered farmhouses along the border. By morning, the forest was wrapped in white so deep it swallowed sound.

Mika Lehtinen stood in that quiet and watched his world change.

He had spent twenty-eight years in these woods. He knew where the rabbits burrowed and the elk crossed; he knew the hollows where snow piled deeper, the little rises that caught the first light of dawn. He knew his rifle, too—an old bolt-action with smooth wood worn by his father’s hands before his own. It had a simple iron sight and a trigger he could feel in his sleep.

The officers at the mobilization point knew none of that.

“Hunter’s toy,” one lieutenant had said, hefting the rifle with a smirk when Mika reported for duty. “We’re fighting an army, not deer.”

“We’ll issue you a proper weapon,” another added, pushing a regulation rifle toward him across the crate that passed for a table. “New stock. Bayonet lug. Good for close work.”

Mika had looked down at the unfamiliar gun, with its stiffer bolt and sights that didn’t quite sit where his eye expected.

“I appreciate it, sir,” he’d said carefully. “But I can make this one sing.”

The lieutenant, a man from the city with clean boots and a brand-new coat, had raised an eyebrow.

“You think that antique of yours is going to impress what’s coming over that border?” he’d asked. “We’ve seen the reports, Lehtinen. Tanks. Automatic weapons. Artillery. Modern war. You want to bring a rabbit rifle to that party?”

Mika had hesitated only a second.

“With respect, sir,” he’d said, “this rabbit rifle doesn’t miss much.”

The lieutenant had snorted but, glancing at the captain filling out forms nearby, seemed to think better of pushing it.

“Fine,” he’d said. “Keep your toy. But when you run out of tricks, don’t say we didn’t try to help.”

Now, as the first distant booms rolled over the trees, Mika rested that same “toy” across the top of the trench and waited.

He could hear the others shifting behind him in the shallow line they’d scraped into the frozen earth. Young conscripts from towns to the south. Men from the mills. A couple of older reservists with eyes that had already seen more than they cared to remember.

“Hey, Mika,” called Antti, the radio operator, huddled behind a stump a few meters away. “You think they’ll see you out there in that coat?”

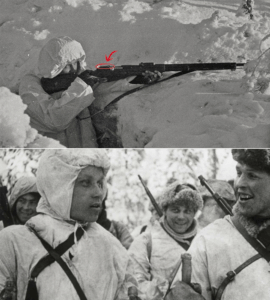

Mika glanced down at himself. His jacket was the same mottled gray-green as everyone else’s, but over it he’d pulled a white hunting smock, the same one he wore every winter, patched at the elbows, hood pulled up. His face, too, was smudged with burnt cork, leaving only the pale stripe of his nose and the steady gray of his eyes.

“I think,” he said quietly, “I’d like them not to.”

Antti chuckled nervously and ducked back to fuss with the radio again, as if pure effort could make the signal stronger.

The blasts grew closer, flinging up fountains of snow and earth somewhere beyond the first line of trees. The air shook, the ground trembled, and then, as suddenly as they had started, the big guns fell silent.

In the quiet that followed, Mika heard it: the faint clank of metal, the low rumble of engines, the distant cadence of boots crunching on packed snow.

The Soviets were coming.

“Positions!” the platoon sergeant hissed down the line. “Eyes open! Nobody fires until they’re in your sights!”

Mika rested his cheek against the cold stock of the rifle, the familiar grain pressing against his skin like an old friend’s hand. He peered through the iron sight at the pale emptiness between the trees and waited.

At first, he saw nothing. Then shapes emerged—dark figures moving against the white, in lines that tried to be straight but broke and wavered around stumps and rocks. Men in heavy coats, rifles slung or held at the ready. Behind them, darker shadows hinted at armored vehicles, their turrets turning slowly.

He knew enough not to stare at the tanks. Someone else would worry about those, with heavier weapons. His world was smaller and more precise.

He scanned for the men who moved differently.

There: one figure at the side, head bare despite the cold, waving a gloved hand, pointing, shouting. Another with binoculars to his face, pausing to look toward the tree line then back toward the rear. A third, a bit farther back, leaned over a map with someone else, gesturing.

Leaders. Eyes. Voices.

Mika let his breath ease out in a slow, controlled stream. The chill bit at his lungs. He barely felt it.

The officer with the map stepped forward to gesture again.

Mika’s finger took up the slack on the trigger.

The rifle’s report was a flat crack that seemed almost swallowed by the snowy air.

Down in the open, the officer jerked, staggered, and folded into the drift.

For a heartbeat, no one moved.

Then the line rippled.

Men crouched, shouted, pointed. Some fired wildly at the trees, muzzle flashes bright against the white. Others dropped behind what little cover they could find.

Mika had already shifted. Three paces to the left, a step back, settling behind a different clump of brush, rifle up again.

He didn’t count his shots in those first minutes. He counted opportunities.

The binocular man dipped and reappeared; when he rose again, looking for a target, Mika was waiting. Another crack, another figure tumbling into the snow, binoculars spinning away on their strap.

A runner dashed forward, message in hand, head low. Mika watched him pass two of his own, then picked a moment when his path straightened and squeezed.

The big machine guns of the defenders opened up then, the forest edge erupting with fire. Others fired in bursts, following shouted orders.

The Soviets kept coming.

They were many. More than Mika liked to think about. They advanced in fits and starts, some hugging the ground, others rising to dash forward. A few fell without Mika’s help, cut down by the machine guns or slowed by mines hidden under the snow.

He did what he had always done: he found the ones who lifted others, and he brought them down.

Once, he felt something slap the snow near his face—a ricochet from a bullet that had landed too close. He rolled, pressed himself flatter, shifted again. The smock blended with the snow; his breath steamed faintly in the frigid air.

When the order to fall back finally came, shouted hoarse along the line, Mika’s fingers were numb, his shoulder bruised, and his count—if he’d been honest with himself—already higher than he’d ever expected it to be in real life.

He did not feel victorious, or heroic, or any of the words thrown around in speeches. He felt tired.

And the day was not done.

They would talk about that first day later, in tents and foxholes and cracked barracks, when someone pulled out a bottle and someone else pulled out their memories.

“You remember Hill Eleven?” Antti would say. “When they decided to test whether snow stopped bullets?”

“Remember when Mika there turned his rabbit gun into a thunderstorm?” another would add. “How many did you get that day, Hunter?”

Mika would shrug, stare into his cup, and say something evasive.

“Enough,” he’d say. “Too many.”

But word traveled.

By the end of the week, the company commander called him in.

“You’re wasted in the line,” Captain Saarinen had said, leaning over a map that never seemed to leave the rough plank table. “I’ve got reports from three platoons and a battalion spotter that you’re hitting targets at… ridiculous distances. With that thing.”

He nodded toward the hunting rifle by Mika’s knee.

“It’s what I know,” Mika said.

The captain studied him.

“You don’t talk much,” he observed.

“I’d rather listen,” Mika replied.

“Good,” Saarinen said. “Then listen now. We’re forming a small unit—independent marksmen. Not just good shots, but men who can move alone, live out in those trees for days, pick off key targets, slow their advance. You’ll be attached to battalion, not to any one platoon. You’ll go where they’re thickest.”

He tapped the map again, finger tracing a line north and east of their current position.

“The Soviets think we’re just going to sit here and wait for them,” he said. “I want them to learn to be afraid of the spaces between. You and a handful of others—if you can handle it—will help teach that lesson.”

Mika had hesitated only a moment.

“What about the others?” he had asked. “My squad?”

“They’ll miss you,” Saarinen had said bluntly. “But they’ll also be able to move because of what you’ll be doing. You’ll save more of them from out there than you will standing next to them.”

He’d met Mika’s eyes.

“It’s not a glamorous job,” he added. “It’s cold, it’s lonely, and you won’t always know what your shots changed. You think you can carry that?”

Mika had thought of his father, teaching him to track elk in the pre-dawn woods. Of the way he’d waited, sometimes for hours, for the right shot. Of the way his father had made him look at the animal afterward, to thank it, to understand.

“War is not hunting,” his father had said once. “Hunting is for food, for respect. War is for when people forget how to talk.”

“Why do people forget?” Mika had asked.

“Because they start counting things instead of listening,” his father had replied.

Now, years later, Mika straightened his shoulders.

“I can carry the rifle,” he told Saarinen. “The rest… I’ll learn.”

Winter bit down harder as the weeks went on.

The sun became a shy thing, skimming the horizon for a few hours each day before diving back behind the trees. The snow deepened, layers upon layers, turning the world into something like a blank page waiting for stories and tracks.

Mika wrote his in faint, careful lines that the wind would erase.

He moved alone or with a partner—another quiet man named Veikko who had the patience to match him. They wore white smocks that made them look like ghosts at a distance. They carried as little as they could: rifle, ammunition, a knife, a small shovel, a pair of binoculars, dried bread and meat, a small stove, a rolled blanket, and, always, a bit of cord because cord was useful for everything.

They slept in snow caves they dug into drifts, or under spruce boughs bent low. They learned how to keep their breath from fogging their scopes, how to insulate their rifles from the cold so the metal wouldn’t crack or seize. They learned which branches made good camouflage and which betrayed them with a shower of snow when touched.

The Soviets learned, too.

At first, they marched in broad columns along the roads, confident in their numbers. A single shot from the tree line would drop a man at the head of the column; a second or third, well-spaced, would take down whoever jumped forward to take his place.

Then the column would bunch, commanders shouting, guns spraying blindly at the forest while the marksmen had already ghosted away.

They started moving in smaller groups after that, hugging cover, sending scouts ahead. That helped, but scouts had to expose themselves to see. A scout with binoculars made a tempting, dangerous ripple against the white.

Mika did not take every shot he saw. Sometimes he merely watched, counted, learned. Sometimes he let men pass unchallenged because they were too many, or too spread out, or because something in his gut told him the risk outweighed the gain.

Other times, he made one shot and changed the shape of a day.

Once, he watched through drifting snow as a Soviet officer gathered his men in a shallow depression for a briefing. They clustered close, heads bent, maps spread over a crate. The officer pointed, gestured back toward the forest.

Mika could not hear what he was saying. He did not need to.

He aimed not at the men in the cluster, but at the radio man standing slightly apart, pack on his back, antenna barely visible above his head. The shot was long, windy, and he almost didn’t take it.

He did.

The radio operator dropped. The antenna fell crooked.

It took the officer a full minute to realize what had happened. By then, the moment of concentration was gone. Men were shouting, pointing; some ran for cover, others fired at shadows.

That day, the attack on the adjacent hill came late and disorganized—late enough for another company to finish laying mines, disorganized enough to be stopped with fewer losses.

Mika never met those men. He heard about it days later, over a shared pot of thin stew.

Somebody said his name with awe. Somebody else called him a ghost.

He did not feel like a ghost when he lay in the cold, stomach cramping from too much dried meat and not enough sleep. He felt as solid and as mortal as any of them.

He started keeping a tally at first, scratched in the back of a small, worn notebook.

Part of it was habit. Hunters counted. Not out of pride, but out of respect for the numbers they took from the woods each season.

Part of it was because the officers asked.

After each mission, he’d report in.

“How many?” someone would ask, pencil poised over a report form.

“Three,” he’d say. “Maybe four. One officer, two runners. One machine gun team, I think.”

They’d nod, scribble, log it in whatever ledger they kept.

The company rumor mill translated those numbers into something larger. Men at the fires would nudge each other.

“They say he’s up to fifty,” someone would whisper.

“Fifty? No. More. Sixty-five at least.”

“No way. That’s a full company!”

Mika heard the whispers and chose not to correct them. Numbers were slippery things.

The official tally grew faster than his notebook. Every time another officer asked—at battalion, at regiment, once even at a rear-area headquarters where a man with polished boots and a sharp pencil questioned him—somewhere, someone added another mark to the legend of the quiet hunter with the “useless” rifle.

By the time they told him he’d passed two hundred, he had stopped counting on paper.

“What difference does it make?” he asked Veikko one night, as they huddled over their small stove in a snow cave.

Veikko blew on his steaming cup.

“It makes the men feel like something big is hitting back,” he said. “They see the tanks, the guns, all that metal. Then they hear that one of theirs, with one old rifle, is out there thinning the edges. Gives them a story when they’re cold.”

“Is that enough?” Mika asked.

Veikko shrugged.

“Nothing’s enough,” he said. “But stories help people do hard things. You’re a story now, whether you like it or not.”

Mika stared at the faint glow from the stove.

“What about us?” he asked. “Do stories help us?”

Veikko smiled without much humor.

“They might, someday,” he said. “When this is over.”

It wasn’t one battle that pushed his unofficial tally to the number that would later stick—478, whispered like a strange combination of praise and disbelief.

It was days and weeks and months of small decisions and cold fingers, of waiting and seeing and deciding not to shoot sometimes as often as deciding to.

There were moments, though, that stood out.

The day they tried to root him out with artillery, for example.

He and Veikko had set up on a low ridge overlooking a frozen river where the Soviets had begun to push supply sleds across. The ice groaned under the weight, cracks spidering out, but it held. Men in greatcoats trudged along, hauling crates of ammunition, fuel, food.

“Too tempting,” Veikko had murmured. “We could cost them a week of supplies here.”

Mika had agreed—until he noticed something else.

On the far bank, an officer and two engineers were inspecting the supports of a hastily built wooden bridge. They measured, marked, waved to a group of men behind a mound of snow. A truck waited, engine idling.

Mika shifted his rifle slightly.

One shot. The engineer with the clipboard dropped, the papers scattering. The officer spun, shouted. Mika cycled the bolt, exhaled, and took the second shot.

The officer fell against the support, leaving a smear on the wood.

Men scrambled, some toward the bridge, some away. The truck lurched, tried to turn, its wheels slipping.

“That was one of your better ones,” Veikko said, watching through his binoculars as the sudden confusion turned the riverbank into a mess.

Mika didn’t answer. He was already sliding back, wary.

Minutes later, the first artillery shell landed where he’d been.

They moved three times that day, each new position lasting only long enough for two or three shots before the counter-barrage zeroed in. Snow and earth exploded around them. Shrapnel whined through the trees.

Once, a shard of metal clipped Mika’s smock, tearing a neat slit. It didn’t touch skin, but it caught his breath. He pressed his gloved hand to the rip, feeling the heat of his own ribs beneath.

“You all right?” Veikko shouted over the din.

“Still here,” Mika called back.

He would sometimes wonder, years later, how many of the men he’d aimed at had similar near misses. How many went home with new rents in their coats and a story about a shot that had almost found them.

On another day, he watched a Soviet sniper hunt one of their own squads.

The enemy marksman had picked a tree on a low rise, high enough to see over the brush, branches thick enough to hide his outline. His first shot had taken the squad leader. The second hit the machine gunner as he tried to set up his weapon behind a rock.

Mika saw the flash, looked for the second, caught the faint movement in the branches.

“He’s good,” Veikko said, spotting the same thing. “Quick. Smart.”

Mika nodded. For a moment, he felt a strange kinship with the unseen man across the field. They were, in different uniforms, doing the same job.

“I’ll take him,” Mika said quietly.

He adjusted his position, inch by inch, until the trunk of a fallen tree framed his view. The enemy sniper had settled into a rhythm: shoot, shift slightly, wait. He was expecting return fire from the squad, not from somewhere farther out and to the side.

When he moved again, turning his head for a better angle, the edge of his cap caught the light.

Mika squeezed.

The shot cracked. The branch shook. A body tumbled from the tree, breaking other branches on the way down.

The squad in the hollow below never knew who had saved them. They only knew that the sudden, deadly accuracy that had pinned them vanished, and they were able to pull back with only two on their improvised sled.

Later, back at a supply point, a shaken corporal told the story.

“Some phantom out there must’ve got him,” he said, hands wrapped around a mug. “One minute we’re stuck, next minute he falls out of the tree. I didn’t see the shot. Just heard it.”

Mika, sitting in the corner with his smock still damp from melted snow, stared into his own cup.

Veikko nudged him.

“He was good,” Veikko said softly.

“Yes,” Mika replied. “Too good.”

“Better he’s not hunting our boys anymore,” Veikko said.

Mika nodded. It was true. It didn’t make the knot in his chest any easier.

The winter did not last forever, though at times it felt like it might.

Eventually, the days grew longer again. The snow crust thinned, turned icy, then dirty. Tracks in it stayed as faint scars instead of fresh lines.

The Soviets, too, adjusted.

They brought more armor, more artillery, more planes. The little forest roads and hidden snow paths that had once been safe arteries became contested ground. Somewhere, far above Mika’s level, men in headquarters tents drew new lines on new maps.

News filtered down in fragments.

They had held here.

They had lost there.

Somewhere else, a city had changed hands twice.

A truce was talked about, then not, then whispered again.

Mika kept moving until an enemy shell finally found him.

It wasn’t dramatic.

He and Veikko had set up near a rock outcrop overlooking a narrow valley where they’d been told a new Soviet supply column might pass. They had been there two hours when the first shells landed, too close for comfort.

“Someone talked,” Veikko muttered as they slid back. “Or they saw something we missed.”

The third shell hit the outcrop.

Mika felt the world punch him in the side. The air disappeared. He found himself on his back in the snow, ears ringing, unable to breathe for a moment.

He tried to move and felt something hot and sharp in his left leg.

Veikko’s face appeared above him, pale and tight.

“Stay still,” Veikko said. “You’ve got a piece in you.”

Mika looked down. His smock was ripped, his trousers beneath darkening. He could feel wet warmth seeping into the cold.

“Oh,” he said, oddly calm. “So that’s how it feels.”

They dragged him out under the cover of smoke and more shells. Half of that day was a blur of pain and jolting sled movement, then a makeshift infirmary in a wooden building that had once been a school.

He drifted in and out of consciousness as a doctor dug the metal out of his leg and stitched it. He heard snatches of conversation.

“Lucky it missed the bone…”

“…no, we can’t send him back to the front like that…”

“…have you seen his record? They want him somewhere safe enough to keep breathing…”

He woke one morning to find Captain Saarinen sitting on the stool beside his bed.

“You look terrible,” Saarinen said with no real malice.

Mika managed a faint smile.

“Feels worse,” he replied.

Saarinen rested his elbows on his knees.

“Officially,” he said, “you’re being rotated to the rear for recovery. Unofficially… you’ve done enough. More than enough. There’s talk of medals. Maybe speeches. Some officer wants to write a paper about your ‘methods.’”

He made a face at the word.

“Methods,” he said. “As if you’re a lab experiment.”

Mika stared at the ceiling beams.

“I don’t want speeches,” he said.

“I know,” Saarinen said.

“I don’t want medals,” Mika added.

“I know that, too,” Saarinen sighed. “But some people feel like they have to hang something on you, to make sense of the stories they’ve heard.”

He hesitated.

“You know what number they’re saying now?” he asked quietly.

Mika closed his eyes.

“I stopped counting,” he said.

“Officially,” Saarinen went on, “between direct reports, corroborated observations, and what our spotters and neighboring units say… they’re putting it at four hundred and seventy-eight.”

The number hung in the air like frost.

Mika’s jaw tightened.

“That’s not a score,” he said.

“No,” Saarinen agreed. “It’s a cost. One part of a very large cost on all sides.”

He reached out and put a hand lightly on the blanket over Mika’s good leg.

“Listen,” he said. “You need to understand something. The men in your company, in your battalion… they’re alive, a lot of them, in part because of what you did. You made dangerous days survivable. You made roads a little less deadly for them.”

He met Mika’s gaze.

“I’m not going to tell you to feel proud,” he said. “That’s your business. I am going to tell you that, in a terrible winter, you did a terrible job as well as anyone could have asked.”

Mika swallowed.

“I remember faces,” he said quietly. “Not all of them. But some. I remember the way the snow moved when they fell. The way the sound took a moment to catch up.”

Saarinen nodded.

“You’ll carry that,” he said. “Probably for the rest of your life. That’s the other side of the story the papers won’t print.”

He stood.

“When you can walk again without that leg folding,” he said, “they’ll give you the option. Go home. Or stay in the rear as an instructor. Teach others what you’ve learned. Maybe teach them the part where you decide when not to shoot as much as when to.”

He half-smiled.

“For what it’s worth,” he added, “I told the quartermaster staff to stop calling that rifle of yours ‘useless.’”

Mika managed a real, if small, smile at that.

“Good,” he said. “It would be rude to insult an old friend.”

War ended the way it often does for the ones not in the rooms with the maps: in rumors and confusion.

A ceasefire was mentioned, then doubted, then confirmed. Shots still rang out in places because nothing stopped on a dime. Men who had been braced for another offensive one week found themselves stacking rifles and staring at the ground the next, unsure what to do with their hands.

Mika went home on a train that smelled of coal and damp wool, his leg stiff, his rifle in a canvas case at his feet.

The farm was smaller when he returned. Or perhaps he had grown.

His father had died the previous year, a quiet passing in a quiet village. His mother hugged him hard and long enough to make his ribs protest. His younger sister laughed and cried in the same breath, calling him by childhood nicknames he hadn’t heard under the snow.

He went back into the woods that first autumn with the same rifle, this time for its old purpose.

The elk were still there. The rabbits still ran.

He found he could not lift the rifle as easily when the sights settled on the broad, calm side of a grazing animal. He forced himself to wait until he knew he’d make a clean shot. He took fewer than before. It felt right.

In the village, stories about the war years lingered. Old men leaned against walls and summarized complex operations into lines like, “We held them at the river,” or, “They came over the ridge like ants.”

Every so often, someone would nudge a friend and point at Mika.

“That’s him,” they’d whisper. “The hunter. The one with the old rifle. You know? Four hundred something.”

Mika would nod politely if he caught the glance, then change the subject.

He built fences. He fixed roofs. He taught children how to walk quietly in the woods so they didn’t scare the birds.

Once, a newspaperman from the city arrived in a car that looked too clean for the road, smelling of ink and cigarette smoke. He asked Mika for a statement. He asked him about the number. He wanted details.

“How did it feel?” the man pressed. “To be so… effective?”

Mika looked at his calloused hands.

“Cold,” he said. “It felt cold.”

The man waited for more. When none came, he left, disappointed.

Years later, on a picnic with his sister’s children, he found himself sitting on a rock overlooking a familiar dip between trees. The kids ran around him, playing some game that involved sticks and shouting. The air was warm. The grass under his hand tickled.

One of the boys, twelve and curious, plopped down beside him.

“Uncle Mika,” he said. “Did you really… you know…?”

He hesitated, struggling with the weight of the question and the bluntness of youth.

“Did I really shoot at a lot of enemy soldiers?” Mika finished for him, keeping his tone gentle.

The boy nodded, eyes wide.

“That’s what they say,” the child went on. “They say you were the best. That your rifle was special. That you were like a ghost.”

Mika looked out at the trees.

“The rifle is a tool,” he said. “I was a man in a terrible time. People like to make stories out of that.”

“But is it true?” the boy pressed. “The four hundred something?”

Mika took a long breath.

“Numbers are strange,” he said. “They make big things sound small. They make people forget that each part of the number was a whole person. With a face. And a family. And someone who waited for them.”

He glanced at his nephew.

“When you hear that number,” he said, “I want you to think less about how big it is and more about how heavy it is. For everyone.”

The boy frowned thoughtfully.

“Do you regret it?” he asked.

Mika considered.

“I regret that there was a war,” he said. “I regret that people decided killing each other was the way to solve what they argued about.”

He tapped the rifle leaning against the rock beside him—old, oiled, cared for.

“I don’t regret trying to keep my own people alive,” he added quietly. “But I will never be happy that it meant taking others away from theirs.”

The boy leaned against him without fully understanding, small shoulder warm against his side.

“Will there be another war?” the child asked.

“I hope not,” Mika said.

He knew hope was a fragile thing. But hope, like a careful shot, was sometimes all a person could take.

As the years went on, fewer people in the village remembered the details of that winter. There were new worries: crops, prices, weather. The younger ones learned about the war from books, from old newsreel footage, from simplified stories.

Occasionally, someone would bring up the old rumor.

“Four hundred seventy-eight,” they’d say over a game of cards. “Can you imagine? With an old hunting rifle.”

“It had to be more,” someone else would argue. “Or less. You know how stories grow.”

Mika would sit in the corner, listening or not, his hands busy mending a net or whittling a piece of wood.

He never corrected them.

The rifle hung above his fireplace, same as it had hung above his father’s. Sometimes he took it down to clean it. Sometimes he took it into the woods. More often, he let it hang as a reminder.

Not of a number.

Of a winter when people with big guns and bigger ideas met a quiet man from the forest and learned that nothing in war was truly “useless” if someone knew how to use it.

And of how he, in turn, had learned that the sharpest edge of that usefulness cut inward as much as outward.

When his time came, much later, after many more quiet years, it was not in a trench or under artillery fire. It was in his own bed, with snow falling outside the window, his sister holding his hand and his nephews and nieces grown.

They found the small notebook in a drawer, the one with the early tallies, stopped partway through. The last number written there was 187. The rest was blank.

“Why did he stop counting?” one of them asked.

Another, older now, remembered that day on the rock.

“Because some things,” she said softly, “are too heavy to fit into a little book.”

They closed it and put it back.

The rifle stayed on the wall.

Sometimes, on long winter evenings, someone would look up at it and tell the old story again.

They would argue about whether it was really that many. They would marvel that a “useless” hunting rifle had made such a difference in such a large war.

But in the quiet moments between those retellings, when the fire burned low and the wind outside sounded like distant echoes, they would also remember the man who had carried it and the way, when asked about what he had done, he had always gone back to one simple truth:

That every shot, in the end, was not about numbers or legends.

It was about trying, in a small, precise way, to hold a fragile line between the people behind him and the people coming over the snow.

THE END

News

Creyeron que ningún destructor aliado sería tan loco como para embestirles de frente en mar abierto, discutieron entre ellos si el capitán estaba desequilibrado… hasta que 36 marinos subieron a cubierta enemiga y, sin munición, pelearon cuerpo a cuerpo armados con tazas de café

Creyeron que ningún destructor aliado sería tan loco como para embestirles de frente en mar abierto, discutieron entre ellos si…

Germans Sent 23 Bombers to Sink One “Helpless” Liberty Ship—They Laughed at Its Tiny Guns, Until a Desperate Captain, 19 Silent Refugees, and One Impossible Decision Changed the Battle Forever

Germans Sent 23 Bombers to Sink One “Helpless” Liberty Ship—They Laughed at Its Tiny Guns, Until a Desperate Captain, 19…

They Dropped More Than a Hundred Bombs on a Half-Finished Bailey Bridge, Laughing That It Would Collapse in Minutes—But the Reckless Engineer, a Furious Staff Argument and the Longest Span of WW2 Turned a River Into the Allies’ Unbreakable Backbone

They Dropped More Than a Hundred Bombs on a Half-Finished Bailey Bridge, Laughing That It Would Collapse in Minutes—But the…

German Aces Mocked the Clumsy ‘Flying Bathtub’ P-47 as Useless — Until One Stubborn Pilot Turned His Jug into a 39-Kill Nightmare That Changed Everything in a Single Brutal Month Over Europe

German Aces Mocked the Clumsy ‘Flying Bathtub’ P-47 as Useless — Until One Stubborn Pilot Turned His Jug into a…

They Laughed at the “Useless Dentist” in Uniform and Called Him Dead Weight, But When a Night Attack Hit Their Isolated Ridge, His Fight With the Sergeant, One Jammed Machine Gun and 98 Fallen Enemies Silenced Every Doubter

They Laughed at the “Useless Dentist” in Uniform and Called Him Dead Weight, But When a Night Attack Hit Their…

They Mocked the ‘Legless Pilot’ as a Walking Joke and a Propaganda Stunt, Swearing He’d Never Survive Real Combat—Until His Metal Legs Locked Onto the Rudder Pedals, He Beat Every Test, and Sent Twenty-One Enemy Fighters Spiraling Down in Flames

They Mocked the ‘Legless Pilot’ as a Walking Joke and a Propaganda Stunt, Swearing He’d Never Survive Real Combat—Until His…

End of content

No more pages to load