The Secret Forests of the Royal Air Force: How Britain Hid Its Planes Beneath Trees, Painted Fake Shadows on Runways, and Fooled the Entire Luftwaffe for Years — The Ingenious Illusion That Turned the Battle of Britain into a War of Deception

In the summer of 1940, the skies over Britain screamed with the sound of engines.

Every dawn, the horizon burned — and every night, the world held its breath.

But beneath the chaos, far from the headlines and the radio speeches, something far stranger was happening.

Deep in the English countryside, hundreds of aircraft seemed to vanish into the trees.

Not destroyed. Not evacuated.

Hidden — in plain sight.

And the Germans never found them.

This is the forgotten story of how Britain won the air war not only with courage, but with illusion — by literally painting shadows on the ground.

Part I — The Vanishing Airfields

By July 1940, the Royal Air Force was outnumbered, outgunned, and nearly out of time.

The Luftwaffe had thousands of planes. Britain had hundreds.

Every time the Germans found an RAF base, they bombed it to rubble.

The problem wasn’t bravery — it was visibility.

A Spitfire sitting on a sunlit runway was an easy target for a German bomber at 20,000 feet.

The Luftwaffe’s reconnaissance aircraft flew over southern England daily, snapping thousands of photos for their analysts in France.

Every hangar, every shadow, every runway line — all catalogued and mapped.

By early August, the RAF knew it couldn’t win in the open.

So, it decided to disappear.

Part II — The Camouflage Command

The man behind it wasn’t a pilot or a soldier — it was Sir Hugh Dowding, head of Fighter Command.

He was methodical, mathematical, and quietly desperate.

When asked how he intended to keep the RAF alive, he simply said:

“Make them see what isn’t there. Make them miss what is.”

That task fell to a curious group few had heard of — the Royal Engineers Camouflage Section, nicknamed “the Camouflage Command.”

Its members were artists, painters, stage designers, illusionists, and landscape architects.

Men and women who once decorated theaters and painted scenery now had to save Britain using paint and canvas.

Their mission: hide the Royal Air Force.

Part III — Forests of Steel

The Camouflage Command’s first breakthrough came when they realized that aircraft, viewed from above, cast distinct shadows — long, dark triangles that betrayed even the best concealment.

A hidden plane under a net was still visible because of its shadow.

So they did something extraordinary:

they painted fake shadows.

They took ordinary airfields, covered the real runways with grass-colored canvas, and painted artificial shadows of hangars and planes in carefully chosen angles, as if the sun were shining from a different direction.

To the Luftwaffe’s aerial cameras, it looked like an airfield full of planes — or an empty field, depending on the day’s illusion.

Sometimes the RAF moved entire airbases into the woods.

They cut narrow strips of grass between trees for takeoff and landing, then covered the aircraft with nets woven from real branches.

Engines were smeared with mud and grease to dull reflections.

Even the tracks left by mechanics were swept clean.

One German pilot later wrote in his diary:

“England is a land of ghosts. Their airfields are never where they were yesterday.”

Part IV — The Fake Airfields

But the deception didn’t stop at hiding — the RAF began creating decoys.

Across southern England, engineers built fake airbases out of wood, canvas, and scrap metal.

They were known as “Q-sites.”

Each fake base had imitation aircraft made of wooden frames and painted canvas, hangars built from tarpaulin, and runways outlined with crushed chalk.

From 10,000 feet, they looked completely real.

At night, these fake airfields came alive.

Electric lamps mimicked landing lights.

Oil drums burned to resemble the glow of engines warming up.

Sometimes, they even had fake mechanics moving cut-out silhouettes on rails.

The Luftwaffe, seeing the lights, swooped in and dropped bombs — wasting precious explosives on nothing but plywood and paint.

A single Q-site could absorb dozens of raids that might have destroyed a real RAF station.

To keep up the illusion, real bases nearby went completely dark.

Pilots took off silently at dawn, while their wooden “ghost twins” burned under German fire a few miles away.

The deception worked so perfectly that German reconnaissance maps began marking these fake bases as “destroyed.”

The real ones, nestled in forests or hidden under painted shadows, carried on undisturbed.

Part V — The Artists of War

Behind every illusion was an artist with a brush, a compass, and nerves of steel.

One of them was Basil Spence, a young Scottish architect who would later design Coventry Cathedral.

During the war, he painted fake hangar roofs and shadow lines so precisely that they fooled the Luftwaffe’s best photo analysts.

Another, Christopher Ironside, designed camouflage patterns for entire airfields — years before he became famous as the man who designed Britain’s first decimal coin.

And then there was Mary Violet Wills, a painter from Chelsea who specialized in nature scenes. She spent months studying how trees cast shadows in different seasons — so she could recreate them perfectly on canvas covers.

She joked that she was “painting forests that didn’t exist, to hide planes that did.”

Their secret studios became laboratories of illusion.

Every brushstroke could save a squadron.

Part VI — The Moment of Truth

In early September 1940, the Luftwaffe launched Operation Adlerangriff — the “Eagle Attack.”

It was meant to crush the RAF once and for all.

Wave after wave of bombers crossed the Channel, targeting airbases and radar stations.

But their reconnaissance photos — the ones used to plan these raids — were riddled with errors.

One intelligence officer in Berlin grew suspicious.

“How can the RAF still fight,” he asked, “when we have destroyed their bases three times?”

What he didn’t know was that the real airbases — Northolt, Tangmere, Biggin Hill — were still operating, their runways camouflaged with paint and leaves, their hangars disguised as barns or shadows.

Even when bombs hit nearby, the pilots simply rolled their Spitfires out of the trees, took off, and met the enemy in the sky.

By October, the Luftwaffe had lost over 1,700 aircraft.

The RAF — battered but alive — still flew.

Hitler postponed the invasion of Britain indefinitely.

The illusion had held.

Part VII — The Forests After the Fire

After the war, the fake airfields were dismantled.

The plywood planes were burned or left to rot in the rain.

Many were forgotten — just empty fields again.

But in aerial photographs taken decades later, faint outlines of those painted shadows could still be seen, ghostly stains on the earth where deception had once been a weapon.

Farmers plowing their land sometimes unearthed strange relics — fragments of canvas, old metal drums, charred wooden propellers.

Few realized they were standing on what had once been Britain’s invisible front line.

Historians later estimated that the camouflage and decoy programs diverted or wasted nearly 10,000 tons of German bombs.

Tens of thousands of lives — civilian and military — were spared because the enemy had been looking in the wrong place.

Part VIII — The Psychology of Shadows

What made the deception so powerful wasn’t just its craftsmanship — it was the understanding of how the human eye lies.

The Luftwaffe’s analysts were experts, but their minds were human.

They expected to see certain patterns: rectangular hangars, neat rows of planes, straight runways.

So that’s exactly what the RAF gave them.

The artists studied aerial photography and learned how perspective distorted color, how the angle of the sun changed every shadow.

They even learned to age fake installations — painting in “wear and tear” to make them look used.

When the Germans compared old photos to new ones, the illusion deepened:

the “destroyed” airfield seemed to have been rebuilt, the “abandoned” base appeared active again.

It was camouflage turned into psychological warfare.

Part IX — The Last Secret

It wasn’t until the 1970s that many of the camouflage records were declassified.

By then, most of the artists had died or moved on to peaceful careers.

When asked about it years later, one surviving member of the Camouflage Command said simply:

“We weren’t soldiers. We just made the enemy believe a story — and they believed it.”

He paused, then smiled.

“Funny thing is, we sometimes fooled ourselves too. There were nights when even I couldn’t tell where the planes really were.”

Part X — The Hidden Lesson

In an age defined by machines and weapons, Britain’s most effective weapon turned out to be imagination.

The wooden planes, the painted shadows, the fake runways — they were all lies, yes.

But they were lies that protected truth: the lives of pilots, the survival of cities, the endurance of a nation.

There’s a peculiar beauty in that.

That art — usually meant to create wonder — could also create safety.

The Camouflage Command didn’t just paint illusions.

They rewrote the rules of war — proving that sometimes, the smartest way to fight is not to fight at all, but to disappear.

Epilogue — The Forests Whisper Still

Today, if you walk through certain woods in southern England, you might find a patch of perfectly level ground, surrounded by trees that seem oddly spaced — too regular, too deliberate.

Look closely, and you might see traces of tarmac under the moss, or metal embedded in old roots.

That’s where the Spitfires once slept, hidden from the sky.

The Germans never found them.

And because they didn’t, Britain endured.

The painted shadows are gone now, but the idea behind them — that creativity can outwit destruction — still lingers, quiet and eternal, like the whisper of engines beneath the trees.

News

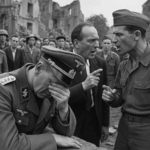

How a Former Colonel Confronted the Collapse of Everything He Once Believed, Faced the Weight of His Past on the Ashes of a Broken Nation, and Spent Three Decades Rebuilding Trust, Bridges, and the Dream of a United Europe

How a Former Colonel Confronted the Collapse of Everything He Once Believed, Faced the Weight of His Past on the…

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose From the Dust to Prove Skill, Honor, and Command Presence Matter More Than Intimidation or Muscle

How a Brilliant Female Operator Turned a Humiliating Challenge Into a Legendary Showdown, Silencing 282 Elite SEALs as She Rose…

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders, and Quietly Shifted the Balance of a War Few Understood Was Already Changing

How a Hidden High-G Breakthrough Transformed Ordinary American Artillery Into a Precision Force, Sparked Fierce Debate Among Scientists and Commanders,…

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a Force Far Stronger and Sparked One of the Most Astonishing Moments of Bravery in Naval History

How a Handful of Outgunned Sailors Turned Ordinary Escort Ships Into Legends, Defying Every Expectation as Taffy 3 Faced a…

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable Trial That Exposed the Fragility of Power and the Hidden Strength of Ordinary People During the Hamburg Crisis

How Overconfidence Blinded Powerful Leaders Who Dismissed Early Air Raids, Only to Watch Their Most Guarded City Face an Unimaginable…

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into the Pivotal Moment Changing an Entire War at the Battle of Midway

How Confident Leaders Underestimated a Quiet Fleet: The Misjudgments, Hidden Struggles, and Unseen Courage That Turned a Calm Ocean into…

End of content

No more pages to load