The Night Roosevelt Read One Quiet Sentence About Normandy—and Answered With Words That Made Everyone in the Room Understand Europe’s Future Was Now

The White House never truly slept in 1944.

It dimmed. It hushed. It changed shifts the way a ship does at sea—lanterns lowered, footsteps softened, voices reduced to murmurs that still carried urgency. The corridors stayed warm, but the air had that late-hour quality of being held in someone else’s breath, as if the building itself was listening for news that could tilt the world.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt sat alone in his study with a lamp lit low and a folder open in front of him. The paper inside had been read by a dozen careful hands before it reached his desk, but it still felt strangely intimate—like a letter addressed to one man and one man only.

Outside, Washington was quiet enough that he could hear the faint rhythm of a distant fan, the soft clink of porcelain somewhere down the hall, and the occasional patter of rain against glass. He was used to those sounds. They were the soundtrack of a presidency lived at the edge of history.

Tonight, though, something else threaded through the quiet.

Waiting.

A knock came—gentle, deliberate.

“Come,” Roosevelt called.

Harry Hopkins stepped in without ceremony. He looked like he always did when the world was heavy: suit a little rumpled, eyes sharp from too many hours awake, the posture of a man who had trained himself to deliver truths without flinching. In his hand was a single envelope, thick and sealed, the edges damp from the rain.

Hopkins crossed the room and set it on the desk as if it might explode if dropped.

Roosevelt glanced at the seal, then at Hopkins. “Is it as serious as your face suggests?”

Hopkins gave him a look that said you already know. “It’s the kind of paper that changes how tomorrow feels,” he said.

Roosevelt’s mouth formed the beginning of a smile and decided against it. He slid the envelope closer and ran a finger along the edge.

“Who’s waiting on the other end of this?” Roosevelt asked.

Hopkins didn’t hesitate. “Everyone,” he said. “In London. In the Channel. In the camps. In the factories. In the towns that don’t know they’re about to become names.”

Roosevelt’s gaze lingered on the lamp’s light pooling over the desk blotter. He had learned, over long months, that war often arrived in the smallest forms—an envelope, a telegram, a sentence that took five seconds to read and years to survive.

He broke the seal.

The folder inside was marked with a bland label that never matched the gravity of its contents. He opened it slowly, as if pacing himself. Hopkins hovered nearby, silent now, hands clasped behind his back.

Roosevelt scanned the first page, then the second. His eyes moved the way a practiced mind reads danger: not in words, but in implications.

He stopped at a single line—typed cleanly, as if typed by someone who didn’t want their hands to shake.

It is the judgment of the planners that the fate of Europe will be decided on the beaches of Normandy.

Roosevelt read it again, because some sentences demanded a second pass simply to confirm they existed.

Then he leaned back slightly. The chair creaked.

For a moment, the room contained only the rain’s whisper and the soft hum of the lamp.

Hopkins cleared his throat once. “They believe the window is narrow,” he said quietly. “Weather, tides, daylight, moon. Everything has to line up. And if it doesn’t—”

Roosevelt lifted a hand, palm outward. Not a stop. More like a gentle request to let the thought finish forming inside him.

He stared at the sentence as if it were a map of the next century.

Normandy.

Not the broad word “France.” Not the comforting abstraction “the continent.” A specific strip of coast, a handful of miles of sand and bluffs and villages that most Americans couldn’t find on a globe without help.

And yet the paper insisted—coldly, confidently—that the future of Europe would pivot there.

Roosevelt looked up at Hopkins. His face was calm, but his eyes had that unmistakable brightness that came when a man felt the weight of being responsible for a world he could not physically hold.

“Do you know what I hear when I read that?” Roosevelt asked.

Hopkins waited. “What do you hear, Mr. President?”

Roosevelt tapped the sentence lightly with one finger. “I hear a door,” he said. “Not a metaphorical one. A real door. Heavy. Stuck. And the only way through is to push it all at once.”

Hopkins exhaled. “That’s about right.”

Roosevelt turned his gaze toward the window, as if he could see across the Atlantic from here. “The planners are right,” he said, voice low. “Not because they want to be dramatic. Because geography doesn’t care about our speeches.”

Hopkins stepped closer. “Eisenhower will want your assurance. He’s ready to carry it, but he needs to know we understand what we’re asking.”

Roosevelt’s mouth tightened. The name “Eisenhower” brought with it a picture of a steady man with steady hands—exactly the kind of man you wanted holding something fragile. And yet even steadiness had its limits.

Roosevelt folded the page carefully, the way a man folds a flag.

Hopkins watched him. “Sir?”

Roosevelt’s eyes returned to the line one more time. Then, as if answering the sentence directly, he said something that did not sound rehearsed. It sounded like a truth he’d been saving.

“Then we will not treat Normandy like a gamble,” Roosevelt said. “We will treat it like a promise.”

Hopkins blinked. “A promise?”

Roosevelt nodded. “A promise to the boys who will go. A promise to the families waiting. A promise to every town in Europe that doesn’t yet know whether it will wake up free or frightened.”

He paused, and when he spoke again, the words came in a tone that carried beyond the room—beyond Hopkins, beyond the rain.

“And here’s what I want delivered to London,” Roosevelt said. “Tell them this: the fate of Europe is not decided by sand. It is decided by will. Normandy is simply where will must show its face.”

Hopkins absorbed that, his expression tightening with relief and dread at the same time. “I can tell them,” he said. “But they’ll ask what you want said publicly.”

Roosevelt’s gaze sharpened, not with anger, but with focus. “Publicly,” he said, “we will say less than we feel and more than we fear.”

Hopkins almost smiled. Almost.

Roosevelt leaned forward again, hands on the desk. “And privately,” he continued, “I want this understood: when the tide turns, we do not hesitate. Not for pride. Not for politics. Not for a headline. If Europe’s future is balanced on Normandy, then Normandy gets our best judgment and our whole heart.”

Hopkins nodded slowly. “That’s what they need to hear.”

Roosevelt lowered his voice. “And Harry—make sure they hear something else.”

Hopkins waited.

Roosevelt tapped the paper once more. “Tell them I’m not asking them to win a day,” he said. “I’m asking them to open a road.”

The next morning, the White House looked normal from the outside.

The flag moved lazily in the damp air. Cars came and went. Secretaries arrived with folders pressed against their coats. Reporters waited with the patience of people who believed the world would eventually confess itself.

Inside, the day carried a different temperature. Orders were spoken with fewer extra words. Telephones rang with a sharper edge. Men who normally joked in hallways nodded instead, as if laughter might waste time.

Roosevelt met with Admiral Leahy before noon. Leahy stood at attention out of habit, even in the presence of a president who didn’t require it.

Roosevelt gestured him closer. “Bill,” he said, “I want to speak plainly.”

Leahy’s jaw tightened. “That would be welcome, sir.”

Roosevelt slid the folder across the desk. Leahy read quickly. His face didn’t change much—he’d been trained to keep his expression from becoming a message.

When he reached the Normandy sentence, he paused.

“That’s a bold assessment,” Leahy said at last.

Roosevelt nodded. “Bold assessments are what we have when the calendar runs out.”

Leahy set the folder down. “If the operation succeeds,” he said carefully, “it changes the entire arc.”

“And if it falters,” Roosevelt replied, “it changes the arc as well—just in a direction none of us can afford.”

Leahy’s eyes narrowed. “The planners believe it is now?”

Roosevelt didn’t answer immediately. He looked down at his hands—hands that had signed laws, soothed crowds, and held the invisible weight of decisions most people never imagined.

“The planners believe,” Roosevelt said, “that history is standing on a narrow porch, and the storm is behind it.”

Leahy gave a short, grim nod. “What do you want from me, sir?”

Roosevelt leaned in. “I want every ship and every supply line treated like it’s part of a single thought,” he said. “No gaps. No careless assumptions. No ‘good enough.’”

Leahy straightened. “Understood.”

Roosevelt’s voice softened, but didn’t weaken. “And I want you to remind the Navy of something,” he said. “When it comes, it will not feel like a grand moment. It will feel like chaos. Don’t let chaos become confusion.”

Leahy looked at him for a beat. “Yes, sir.”

As Leahy turned to go, Roosevelt added, almost casually, “Bill.”

Leahy stopped.

Roosevelt’s eyes were steady. “Tell the men who will be out there,” he said, “that the country sees them. Even if no one can see them through the fog.”

Leahy’s throat moved as he swallowed. “I will, sir.”

That afternoon, Roosevelt met with a small circle—Hopkins again, a handful of advisers, a few men who carried the map of Europe in their heads as if it were a personal memory.

They spoke about tides and timing, about the necessity of deception, about the hard arithmetic of moving entire armies across water.

Roosevelt listened more than he spoke. When he did speak, it was with precision.

At one point, an adviser said, “Mr. President, it may be the decisive point of the war.”

Roosevelt lifted his eyebrows. “It will be,” he said, “if we behave as if it is.”

The man frowned slightly. “Sir?”

Roosevelt’s voice became firm. “There is a habit,” he said, “of treating great operations like they are separate from the people who must endure them. Normandy is not a concept. It is a night for a man who will not sleep, a letter for a mother who will not know what to do with her hands, a sunrise for a soldier who will remember it for the rest of his life.”

The room grew quiet.

Roosevelt looked from face to face. “So I am asking you all,” he continued, “to plan as if you were sending your own sons.”

No one challenged him. No one needed to.

Hopkins scribbled notes. A staffer adjusted his glasses with fingers that trembled just slightly.

Roosevelt leaned back, eyes narrowed with thought. “And I want something else prepared,” he said.

“One of the advisers asked, “Another message to Churchill?”

Roosevelt shook his head. “Not to Churchill,” he said. “To the public.”

Hopkins looked up. “A speech?”

“Not a speech,” Roosevelt replied. “Something simpler. Something that can live in a living room, not just a newspaper.”

The adviser frowned. “What do you mean?”

Roosevelt’s gaze turned inward, as if he were listening to the country itself.

“I mean,” he said slowly, “that when Normandy begins, people will want to hold onto something that isn’t rumor. Something steady. I want to give them words they can say without feeling foolish.”

Hopkins understood first. His eyes softened. “A prayer,” he said.

Roosevelt nodded once. “Yes,” he said. “A prayer—not to sound holy, but to sound human. Because that’s what the moment will demand.”

One of the men shifted uncomfortably. “Sir, some will criticize it.”

Roosevelt looked at him with a calm that had ended many debates. “They are welcome to criticize,” he said. “But they will do it in peace because others did not have the luxury of waiting.”

Night fell again, and the White House returned to its quiet waiting.

Roosevelt sat with Hopkins once more, the lamp lit, the rain replaced by a wind that worried at the window frames.

Hopkins laid out an updated briefing. “Eisenhower is still weighing the weather,” he said. “The whole thing rides on a narrow band of conditions.”

Roosevelt nodded, reading. “It always comes down to weather and men,” he said. “The two things you can’t command.”

Hopkins hesitated, then said, “Sir, there’s something else.”

Roosevelt looked up.

Hopkins’s voice lowered. “There are… doubts in some corners. Not about the necessity. About the cost.”

Roosevelt’s eyes didn’t move. “There should be doubts,” he said. “Only a fool has none.”

Hopkins leaned forward. “What if the doubts become fear?”

Roosevelt set the paper down. For a moment, he didn’t look like a president. He looked like a man whose body carried private pain and whose mind refused to be bent by it.

Then he spoke, and the words were not loud, but they filled the room with unmistakable authority.

“When I learned that Europe’s fate would be decided in Normandy,” Roosevelt said, “I did not feel certainty. I felt responsibility.”

Hopkins watched him closely.

Roosevelt continued. “And responsibility,” he said, “is not a trumpet. It is a hand on a shoulder. It is a promise you keep even when you’d rather not make it.”

Hopkins nodded faintly, as if something inside him had eased.

Roosevelt’s voice sharpened into something like a vow. “So if anyone in London asks what I said when I understood what Normandy meant,” he went on, “tell them this.”

He paused, making sure the sentence landed exactly where he wanted it.

“Tell them I said: We will not ask history for permission. We will do what must be done, and we will do it together—without flinching, without vanity, and without leaving anyone behind.”

Hopkins inhaled, slow. “That’s… strong.”

Roosevelt’s expression softened. “It has to be,” he said. “Because weakness is contagious. So is courage.”

Hopkins glanced down at his notes. “Eisenhower will want to know you stand behind him.”

Roosevelt nodded. “He does not need a cheer,” he said. “He needs a steady light.”

Hopkins looked up. “And the country?”

Roosevelt looked toward the window again, as if imagining the dark ocean between here and there. “The country,” he said quietly, “needs to feel that Normandy is not just a faraway place. It is the hinge on which their children’s world will swing.”

He paused.

“And that,” Roosevelt said, “is why I’ll speak to them when it begins. Not as a commander. As a fellow citizen who is also afraid—and chooses not to let fear steer.”

Days later—when the operation was no longer a folder on a desk but a vast motion in the world—Roosevelt sat at a microphone with papers in front of him and the weight of millions of listening ears pressed invisibly against the walls.

Hopkins stood off to the side, watching the president’s face.

Roosevelt’s voice, when it came through the radio, did not carry the swagger some wanted. It carried something better: steadiness. The kind that tells frightened people they are not alone.

He spoke in a way that did not linger on details that would later be debated in books. He spoke in a way that met the moment where it lived—in kitchens, in factories, in quiet bedrooms where someone stared at the ceiling and tried to imagine a coastline they had never seen.

And those who listened felt, even if they couldn’t name it, that Roosevelt had made an invisible bridge: from the beaches of Normandy to the heart of America.

Later, after the microphone cooled and the room returned to its hushed state, Hopkins approached him.

“You did what you said you would,” Hopkins murmured. “You gave them something steady.”

Roosevelt’s eyes were tired. But behind the tiredness was resolve.

He looked at Hopkins and spoke softly, almost as if finishing the thought that had begun the night he read that sentence.

“Normandy decides,” Roosevelt said, “not because we want it to be dramatic. Because sometimes the world chooses one narrow place to test whether people mean what they’ve been saying.”

Hopkins nodded, voice barely audible. “And do we?”

Roosevelt didn’t hesitate.

“We do,” he said. “We must.”

He rested a hand on the edge of the desk. “And when the history books are written,” he added, “I hope they won’t say we were fearless.”

Hopkins frowned slightly. “What should they say?”

Roosevelt’s mouth formed a small, tired smile.

“I hope they say,” Roosevelt replied, “that we were afraid—and we went anyway.”

He looked down at the papers, then up again, as if seeing through walls and oceans.

“That,” he said, “is how Europe’s fate is decided. Not by perfect plans. By human beings choosing to move forward when the moment demands it.”

The White House remained quiet around him.

But somewhere beyond the windows, beyond the city, beyond the Atlantic and its restless darkness, the hinge of history was turning—slowly at first, then with gathering force.

And Roosevelt, having read one sentence that named Normandy as the place where Europe would be decided, had answered it with words meant to outlast the weather:

A promise.

A steadiness.

A refusal to flinch.

THE END

News

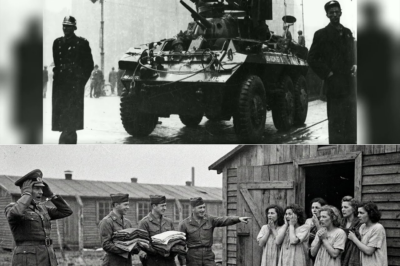

Shock in a Quiet Barracks: A Wehrmacht General Demanded Answers, and What He Saw in the American Women’s POW Ward Rewrote His Beliefs Overnight

Shock in a Quiet Barracks: A Wehrmacht General Demanded Answers, and What He Saw in the American Women’s POW Ward…

The Moment a Captured German General Misread the Scene—and Then Realized the Americans Were Doing Something His Own Army Never Learned: Mercy With Rules

The Moment a Captured German General Misread the Scene—and Then Realized the Americans Were Doing Something His Own Army Never…

A Captive General Asked for ‘His Women’—But the Americans Led Him Through a Quiet Barracks Where Compassion, Not Revenge, Delivered the Sharpest Defeat

A Captive General Asked for ‘His Women’—But the Americans Led Him Through a Quiet Barracks Where Compassion, Not Revenge, Delivered…

When a German General Visited an American POW Camp and Froze—Because the Prisoners Looked Healthier Than They Did at Home

When a German General Visited an American POW Camp and Froze—Because the Prisoners Looked Healthier Than They Did at Home…

When the West Stopped at the Elbe: The Meeting Where Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton Realized the Red Army Would Reach Berlin First

When the West Stopped at the Elbe: The Meeting Where Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton Realized the Red Army Would Reach…

In the Cellars of Berlin, They Whispered “It’s Not Rumor Anymore” as Strange Voices Rose Up the Stairwell and the City Finally Felt Its End

In the Cellars of Berlin, They Whispered “It’s Not Rumor Anymore” as Strange Voices Rose Up the Stairwell and the…

End of content

No more pages to load