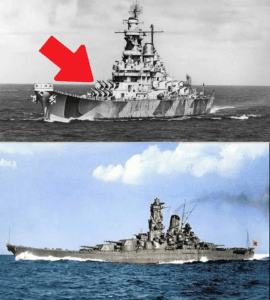

The Morning Three “Tin Can” Destroyers Turned into Lions, Charged a Wall of Japanese Battleships off Samar, and Somehow Saved an Entire Invasion Fleet With Torpedoes, Smoke, and Sheer Stubborn Courage

The morning the world turned upside down smelled like coffee, diesel, and hot metal.

Lieutenant Jack Taylor was standing on the starboard bridge wing of the destroyer USS Hollister when the sky over the Philippine Sea began to blush gray. The escort carriers of Taffy 3 plodded ahead, their flat decks dark shapes against the dim horizon, throwing white wake behind them. The sea was almost annoyingly calm.

It was October 25, 1944. Off Samar Island. The invasion of Leyte was well underway. The big battles, everyone said, were elsewhere— to the north with the decoy carriers, to the south with old battleships trading blows in classic style.

Back here? Just “the baby flattops” and their screens. This was supposed to be the easy side of the war.

Jack took a sip from his mug and leaned on the rail. Down below, on the destroyer’s bow, men were rinsing salt crust from the five-inch mounts. Someone laughed at a joke he couldn’t hear. On the carrier Gambier Bay ahead, a single fighter squatted on the deck like a sleepy cat waiting for dawn.

“Almost peaceful, isn’t it?” said a voice beside him.

Jack glanced over. It was Lieutenant Commander Stan Briggs, the captain— stocky, square-jawed, always with that permanent squint of a man who’d spent too many watches peering into spray.

“Almost,” Jack agreed. “Sir, if the war keeps giving us mornings like this, I might actually start to believe in luck.”

Briggs snorted. “Don’t you dare say that out loud, Mister Taylor. You’ll jinx the whole damned Pacific.”

They stood in companionable silence for a few seconds, listening to the low hum of the ship’s engines.

Then the calm shattered, not with a boom, but with a thin, sharp voice from the mainmast.

“Bridge, lookouts!” The shout knifed down from above. “Many ships on the northern horizon, sir! Big ones!”

Jack felt his stomach drop, as if the deck had tilted.

“Big ones?” Briggs snapped. “Clarify, sailor! How many and what kind?”

“I—I can’t count ‘em all yet, sir,” the lookout stammered. “But I see pagoda masts. Lots of them. Battleship silhouettes. They’re… they’re coming this way.”

Briggs’ eyes went flat. That look Jack had learned to recognize: not panic, but cold, focused anger.

“Sound general quarters,” the captain said. “Now.”

The klaxon howled through the ship.

The transformation was instant. Loose laughter vanished; mugs were abandoned half-finished. Men sprinted to battle stations, boots pounding on steel decks. Hatches slammed shut. Ammunition hoists whined alive. The five-inch mounts snapped around, great gray snouts seeking targets they couldn’t yet see.

In the Combat Information Center, the world became rings of green light.

Jack slipped through the hatch into CIC, the air hot, crowded, and already smelling of sweat and tension. Radarscopes glowed. Voices overlapped: bearings, ranges, confirmations. Someone swore under their breath.

“Talk to me,” Briggs demanded from the doorway.

The radar officer pointed at the scope. “Contact bearing zero-one-five true, range about twenty miles and closing. Multiple large surface contacts. A lot of them.”

“Thought the Japanese battleships were getting pounded down south,” Jack muttered.

“Apparently somebody forgot to tell these guys,” the radar man replied.

Jack felt the argument forming in the room before anyone spoke. It wasn’t about data; it was about what the hell to do next.

Rear Admiral Clifton “Ziggy” Sprague, commander of Taffy 3, came over the TBS radio, voice tight but clear.

“All units, all units, this is Taffy 3. Enemy surface force bearing north, range decreasing fast. Carriers, come to course one-six-zero, make best speed away from enemy. Destroyers and escorts… stand by for further instructions.”

Jack shot Briggs a look. “Sir, if those are battleships—”

“We run,” someone said flatly. It was Lieutenant Greeley, the operations officer. His face was pale in the glow. “We have to. We’re screening escort carriers with tin cans and destroyer escorts. We’re not built to slug it out with battlewagons.”

“We can’t outrun their big shells,” Jack countered before he could stop himself. “Not if they’re already at twenty miles and closing. Their main guns reach out to what, thirty… thirty-five thousand yards? They’ll be shooting while we’re still figuring out which way is safer to die.”

Greeley turned on him. “What do you want us to do, Taylor, charge them? We’ve got five-inch guns and ten torpedoes. They’ve got eighteen-inch rifles and armor thick as my ego.”

The room crackled. It wasn’t just a difference of opinion; it was the kind of argument that sharpened on fear, becoming serious and tense in the space of a breath.

“At least if we run, we buy time,” Greeley insisted. “The carriers can launch planes, we can lay smoke—”

“And if we don’t slow those ships down somehow,” Jack said, voice low, “they’ll run right over the baby flattops and everyone on them. We’ll just be watching when it happens.”

Briggs held up a hand.

“Enough,” he said. “Save the shouting for the enemy.”

He stepped fully into CIC, shoulders filling the cramped space. The noise dimmed. Men looked at him.

“Here’s what we know,” Briggs said. “Center Force— if that’s what this is— got past our boys last night. We’ve got three destroyers and four DEs screening six slow escort carriers. Out there—” he jerked a thumb toward the hull “—is at least one Japanese battleship and a bunch of cruisers. Maybe more. They’re between us and the open ocean.”

He looked at Jack, then Greeley. His jaw tightened.

“We could run,” he said. “Lay smoke. Hope their aim is bad, and our friends in the air get here fast.”

He shook his head.

“But the carriers can’t outrun shells, and we can’t outgun them from back here. The only chance— and I mean the only damn chance— is to make those big boys nervous. Make them think we’re more than what we are.”

He reached for the voice tube.

“Bridge, Captain. Bring us around to a northerly heading. Increase speed to flank. Pass the word to all hands: we’re going in.”

Greeley stared. “We’re charging them?”

Briggs met his eyes. “We’re destroyers, Mister Greeley. This is what we were built to do.”

He glanced at Jack.

“Get topside, Taylor,” he said. “You’re my eyes. And tell the torpedo officer I want a spread worth remembering.”

Jack’s mouth was dry. “Aye, aye, sir.”

As he pushed back out onto the open bridge, the distant horizon flickered.

Someone had fired the first salvo.

They saw the enemy ships before they heard the shells.

At first, they were just shapes on the horizon— low gray smears under the morning sky. Then the details sharpened. Pagoda masts. Tall stacks. Long, graceful bows cutting the water. Two hulking silhouettes, larger than anything else, towered over the column: battleships.

“Jesus,” someone whispered.

The destroyer helmsman stole a look. “Those things are huge.”

“Eyes on your compass,” Jack snapped, more sharply than he meant to. “And keep us steady. We’re already getting more attention than we deserve.”

The radio crackled with Sprague’s voice again, tense but edged with steel.

“To all destroyers: small boys, attack. Repeat, small boys, attack. Lay smoke. Launch torpedoes. Give the carriers a chance.”

On the flag hoist on the nearest escort carrier, signalmen scrambled, hoisting flags that translated to one brutal, simple order:

ATTACK.

Jack felt the deck vibrate harder as Hollister came around to face the enemy. Her bow knifed through their own carrier wakes, turning toward the distant thunder.

To port, he saw their sister ships Jameson and Klein also turn, three destroyers breaking away from the carriers like wolves leaving the herd.

“Signal to the others,” Briggs said. “We’ll form a line abreast. We go in together.”

“Aye, sir,” Jack said. His throat felt tight. “Sir… permission to speak freely?”

Briggs glanced over. “Make it quick.”

“If we do this right,” Jack said, “they’re going to be shooting everything they’ve got at us.”

Briggs’ eyes crinkled in something like a smile.

“If they’re shooting at us, Mister Taylor,” he replied, “they’re not shooting at the carriers. That’s the whole point.”

He stepped to the edge of the bridge, grabbed a voice tube.

“All hands, this is the Captain,” he said. Every corner of Hollister heard him. “We’ve got a big Japanese surface force ahead: battleships, heavy cruisers, the works. Our carriers are already running. Our job is to go make life hell for those big boys. We will lay smoke. We will close to torpedo range. We will take whatever comes and keep going as long as this ship can move.”

He paused.

“I won’t pretend this is a fair fight,” he said. “It’s not. But a fair fight is a luxury for people who aren’t in a war. We are. So we’re going to do the one thing destroyers do better than anything else in the world: we’re going to attack hard and fast and make the enemy worry about us instead of our boys behind us. That’s how we win today.”

He hung up the tube.

“Lay smoke,” he ordered. “All ahead flank.”

“Hollister to Taffy 3,” Jack transmitted on the TBS. “We are commencing torpedo attack.”

The sea behind them blossomed white and gray as smoke generators roared to life. A wall began to grow between the carriers and the enemy, thickening, curling. The sun, just clearing the horizon, turned it into a ghostly curtain.

Out beyond it, the Japanese battleships fired again.

Jack saw the flashes first: bright, almost pretty bursts along their sides. A few seconds later came the distant, rolling thunder of their main guns. Then, a heartbeat after that, the sky overhead ripped open.

Great columns of water leapt up around the destroyer, towering, white. One crashed barely fifty yards off the beam, drenching the bridge with spray and tossing the ship like a toy.

“Shell splash, port side!” someone yelled unnecessarily.

“They’re straddling us,” Jack muttered. “Adjusting fire. Next one might be on the money.”

“Good,” Briggs said. “That means they’re looking at us. Torpedo officer! How long until we’re in range?”

“Torpedo tubes report we can fire in five minutes, Captain,” came the reply. “Closer is better.”

“Closer it is,” Briggs said. “Helm, give me a little more to starboard. Let’s cross their T.”

Jack clung to the rail as Hollister charged ahead, her bow pointing at a line of enemy guns that could rip her open like a sardine can.

He’d been in scary situations before— night actions, air attacks, near misses. But this? Charging battleships with a thin-skinned destroyer?

This was insanity. This was bravery. Maybe both were the same thing.

The next salvo hit closer.

A flash, a roar, and suddenly the world went white. Jack felt the concussion like a giant invisible fist. His ears rang. The bridge deck shuddered under his boots. When the water cleared from his eyes, there was a jagged tear in the air where a shell had burst uncomfortably close overhead.

“Damage report!” Briggs barked.

“Minor shrapnel damage topside,” came the reply. “No major hits yet. Some antennas down. Steering and engines answering.”

“Yet,” Jack repeated under his breath.

He glanced aft. The other two destroyers were with them, foaming wakes cutting arcs toward the enemy. To their rear, the destroyer escorts— smaller, slower, barely more than tin cans with guns— were also following, their captains apparently deciding that if the big boys were crazy enough to charge, they’d be damned if they hid behind them.

The Japanese formation grew. Jack could now pick out individual turrets, superstructures, even tiny dots that had to be men on their decks. He saw the muzzle flashes of secondary batteries starting to fire, sheets of orange licking along cruiser hulls.

“They’re bringing their five-inchers and six-inchers into play,” he said. “We’re about to be in the middle of a very angry punch bowl.”

“Hate to break up your poetry, Taylor,” Briggs replied, “but we’ve got just about one minute to torpedo range. Torpedo officer, stand by.”

Down on the torpedo deck, sailors with towels around their necks and cigarettes clenched in their teeth sprinted between tubes, yanking out locking pins, adjusting gyro angles. Jack knew most of their names. He tried not to think of that.

“Range twelve thousand yards and closing,” came the calm voice from CIC. “Recommend firing at ten.”

“Make it nine,” Briggs said. “If we’re going to do this, we might as well make ‘em jump.”

Another salvo came in. This time, they weren’t so lucky.

A shell slammed into the water so close off the port bow that it felt like the ocean itself had exploded. Shrapnel whined. Jack flinched as a chunk of metal the size of his fist tore through the bridge wing awning, missing his head by inches. Someone behind him screamed.

He spun. Seaman Brandt, the young signalman, was down, clutching his arm, blood seeping between his fingers.

“I’m okay, sir!” Brandt gasped, eyes wide but clear. “Just a scratch— I think.”

“Corpsman!” Jack shouted. A medic scrambled up, grabbed the kid, and hauled him down.

The ship kept going.

“Range nine thousand!” CIC called.

Briggs nodded once. “Torpedoes… fire!”

The firing order rippled down the ship. On each side, Hollister’s quintuple torpedo mounts belched one fish after another, long gray cylinders streaking into the sea with a hiss and a splash. Plumes of spray marked their entry. Then they vanished, invisible death running low and fast.

“Spread one away,” the torpedo officer reported. “Spread two away. Godspeed, boys.”

Jack watched the enemy line.

For a few agonizing seconds, nothing changed. The Japanese ships sailed on, beautiful and deadly, marching inexorably forward. Their guns kept flashing, their shells kept falling.

Then, slowly, Jack saw it: one of the leading heavy cruisers began to turn, not gracefully, but with an urgency that bent its wake into a harsh white curve.

“They’re zigging!” he shouted. “They see ‘em!”

The cruiser’s bow swung hard to port. A battleship behind it began a slower, ponderous turn. Another ship in the column— a second heavy cruiser— hesitated for a crucial moment, caught between obeying its own captain and not colliding with the ship ahead.

In that hesitation, fate grabbed it by the throat.

A white plume shot up halfway along the cruiser’s hull, taller than the mast, thicker than any shell splash. The column of water was shot through with black fragments— metal, paint, maybe more. A split second later, a muffled boom rolled across the water, heavy and low.

“Hit!” someone screamed on Hollister’s bridge. “We got one!”

The cruiser staggered, its bow lifting slightly as its midsection seemed to sag. Smoke poured from the impact point. Flames licked along the deck.

Jack didn’t cheer. He didn’t have time. A salvo from the damaged cruiser’s friends was already on the way.

Three shells crashed around Hollister, one close enough that Jack felt heat and pressure on his face. Another glanced off the destroyer’s aft superstructure with a shriek, punching through metal, starting a fire.

“Fire aft!” came the panicked call over the general announcing system. “Fire in the aft deckhouse!”

“Get damage control on it,” Briggs snapped. “We’re not done here yet.”

He turned to Jack.

“Pass the word to the other destroyers,” he said. “If they’ve got torpedoes left, this is the time.”

Across the smoke, Jack saw Jameson making her own attack run, bow pointed like a spear toward a different battleship. Amid the chaos, he watched tiny flashes leap from her torpedo tubes. A few moments later, another Japanese cruiser began a frenzied turn, white water foaming under her hull.

Above them, aircraft from the escort carriers, armed with whatever they could scramble on short notice— some with bombs, some with rockets, some with nothing but machine guns and courage— dove and swooped. They strafed, dropped, buzzed, harassed. A Wildcat fighter made a fake torpedo run with nothing but its shadow, and still the Japanese gunners flinched, wheeling big guns to chase it.

Everything added up: smoke, torpedoes, harassing air attacks, the unexpected charge of three destroyers and their escorts. The carefully ordered Japanese battle line began to look less like a parade and more like a bar fight.

The argument in CIC earlier— run or charge— suddenly felt like a lifetime ago. The decision had been made. They were in it now.

The enemy adapted.

They shifted fire more fully to the destroyers, clearly deciding that these annoying little ships throwing out torpedoes and smoke were a bigger problem than the slow, fleeing carriers further back.

It was exactly what Hollister and her sisters wanted. It was also lethal.

Shells walked closer. One finally found home.

There was no warning, just a blinding flash and a blow that felt like God had kicked the ship.

Jack hit the deck. When his vision cleared, the bridge was a mess of smoke and ringing ears. A chunk of bulkhead hung at a bad angle. Sparks spattered from a shattered instrument panel.

“Report!” Briggs shouted hoarsely, wiping blood from a cut on his forehead.

“Hit on the forward stack, Captain,” came the reply from CIC. “We’ve lost one boiler, speed dropping. Minor flooding in compartment B-3. We’re still afloat.”

Jack crawled to the edge of the bridge wing and looked down. The aft deckhouse was scarred and blackened, but the fire teams were on it. Men with hoses and extinguishers moved like ants. One of the five-inch turrets was silent, its barrel drooping, smoke seeping from a ragged hole in its base.

On the port side, a sailor lay facedown, motionless.

Jack shut his eyes for half a second, then opened them.

“Engine room says we can give you twenty knots, maybe twenty-five,” the phone talker said, relaying from below. “Any faster and something’s going to blow, Captain.”

“Twenty-five will have to do,” Briggs replied. “We’ve done our damage. Time to spread out and keep their heads down.”

He looked at Jack, eyes bright with adrenaline. “Mister Taylor, let’s lay heavier smoke and start weaving. We’re not much use as a torpedo boat anymore, but we can sure as hell be a moving smoke generator.”

“Aye, sir.”

As Hollister swung away from the Japanese line, her decks scarred, her crew battered but unbroken, Jack caught glimpses of the larger battle beyond their immediate horizon.

He saw Klein take a hit that blew her bow into a geyser of spray, then stubbornly keep firing. He saw a destroyer escort, the small Harmon, charging in closer than anyone had business being, her single five-inch gun blazing at a cruiser like a terrier barking at a bear.

He saw one of their escort carriers, Gambier Bay, stoically staying in formation despite being nakedly vulnerable. He watched as she took straddling salvos from a heavy cruiser, her thin skin no match for big shells. Smoke poured from her side. She slowed, fell behind.

“Come on, girl,” Jack muttered. “Keep going. Just a little longer.”

Planes kept launching from any deck that could fly them. Pilots took off into a sky full of flak and bigger guns not knowing if they’d have a ship to land on when they came back.

Above it all, the Japanese admiral in command of the battleships— Kurita, intelligence said— had to be staring at this chaotic, smoking mess and trying to make sense of it.

He had come here expecting to pounce on helpless escort carriers, maybe some cruisers. Instead he was looking at walls of smoke, wild torpedo attacks, dozens of aircraft, and destroyers that refused to die politely. The radio logs intercepted later would show his staff arguing about what they were really facing.

Cruisers? Fleet carriers? A trick? A trap?

In Hollister’s wardroom, temporarily pressed into service as a secondary CIC after the hit on the superstructure, Greeley slammed a fist down on the chart table.

“They’re turning away,” he said, disbelief and elation fighting for space in his voice. “Look at this— the lead battleship is swinging north. Cruisers are falling back. Their formation is a mess.”

Jack, leaning on the doorframe with soot on his face, stared at the plot.

“They’re… retreating?” he said, the word feeling strange on his tongue. “Those big sons of guns had us cold, and they’re actually turning around?”

“Maybe they’re low on ammo,” someone suggested.

“Maybe they finally realized how many planes we can throw at them,” another said.

“Maybe,” Greeley added quietly, “they decided chasing what they thought were fleet carriers through torpedo water, with destroyers charging them like madmen, wasn’t worth losing half their force.”

The argument from earlier— whether to charge at all— echoed in Jack’s head.

If we run, we buy time.

If we don’t slow them down, they’ll run right over the baby flattops.

“We did this,” Jack said slowly. “Not Hollister alone, but… all of us. The smoke, the torpedoes, the planes making fake attacks even when they were out of ammo. We made them think twice.”

Briggs appeared in the doorway, looking ten years older and strangely lighter at the same time.

“Gentlemen,” he said. “Word from Taffy 3 command: the enemy force is withdrawing to the north. We’re to maintain a screening position between them and the carriers in case they change their minds. But it looks like… they’re done here.”

The tiny wardroom, crowded with smudged faces and sweaty uniforms, erupted. Some men cheered. Some laughed a little too high. One sat down hard on a bench and put his head in his hands, shoulders shaking.

Jack just leaned against the bulkhead and let his knees go weak for a moment.

“We charged Japanese battleships,” he said softly. “And we’re still here.”

Greeley looked at him, eyes red.

“Guess your crazy idea wasn’t so crazy,” he said.

“It wasn’t my idea,” Jack replied. “It was the old man’s. And Sprague’s. And whoever first decided to build destroyers with more guts than sense.”

Briggs gave them both a look.

“Make no mistake,” he said. “We didn’t ‘win’ this in the way the history books like to show, with some clean surrender on a pretty battleship deck. We lost ships. We lost men. Gambier Bay is gone. So is Klein.” His voice caught for a heartbeat when he named the destroyer that hadn’t answered the last roll call.

“But,” he went on, “the troop transports off Leyte— the soldiers going ashore— they don’t know any of that yet. All they’ll know is the battleships never showed up to blow them out of the water. And that is what matters.”

Jack nodded. He saw, in his mind’s eye, the silhouettes of those towering Japanese ships fading into morning mist, their big guns silent, their bows turning away. He pictured the confusion on Kurita’s bridge. The frustration. The second-guessing.

A handful of thin-skinned destroyers and destroyer escorts, backed by outgunned escort carriers and whatever aircraft could scramble, had made a concentrated strike force turn tail.

Nobody would have bet on that at sunrise.

In the days that followed, the story spread like contraband.

Pilots landed on battered decks and talked about destroyers charging through their bombing runs, five-inch guns blazing, even as water fountained all around them. Survivors from sunk ships were pulled from the sea, teeth chattering, eyes wild, telling anyone who would listen how their captains had taken them “in to knife-fighting range with battleships bigger than office buildings.”

At an improvised memorial service on Hollister’s forecastle, with a makeshift flag hanging at half-mast, Jack listened as Briggs read the names of men who would not be coming back. The list included friends, rivals, that young signalman Brandt who’d insisted he was “just scratched” and had later died quietly in the tiny sickbay.

When Briggs finished, he closed his worn Bible and looked out at the sea.

“Some day,” he said, “people back home are going to look at this battle and treat it like a story, with neat lines and neat lessons. They’ll call it the Battle off Samar. They’ll say it was the day destroyers charged Japanese battleships and somehow won.”

He met Jack’s eyes briefly.

“But we know better,” Briggs went on. “We know it was messy. We know it was close. We know a lot of brave men paid the price. Remember that. Remember them.”

He swallowed.

“And remember this, too: when the big ships weren’t there, when the odds were bad and the sky was full of smoke, nobody here waited for someone else to be the hero. The ‘tin cans’ didn’t stay back. They went forward. They did their damned jobs.”

Jack looked up at the sky. It was a clear, brilliant blue now, the kind you saw on peacetime postcards.

He wondered what the Japanese sailors on those battleships were thinking, steaming north again. Had any of them stood on their own decks, staring back at the faint smudge of smoke on the southern horizon, and thought: We were supposed to crush them. And they made us run.

Years later, in interviews and memoirs and history books, survivors would say that the Battle off Samar was one of those rare days when sheer guts made a tangible, strategic difference. When destroyers and destroyer escorts— “tin cans”— fought so fiercely that a powerful enemy force turned away from an easy slaughter.

They would talk about the charge of the small boys. About torpedo wakes glistening like silver snakes. About shells the size of small cars whistling overhead. About smoke so thick it felt like sailing through night at noon.

Some would focus on names that would become famous: captains who earned Medals of Honor, ships that died with their guns still firing. Others would remember quieter details: a scared kid in a gun mount reloading until his hands bled, a cook who became a stretcher bearer without being asked, a communications officer who kept talking calmly into a shattered headset while chaos howled around him.

Jack, in the years after the war, would be asked about it more than once.

“What was it like,” people would say, eyes wide, “to charge battleships in a destroyer?”

He always struggled to answer.

“It was loud,” he’d usually start. “It was confusing. It was terrifying. It was… everything you think it was, and also nothing like it.”

He’d pause, remembering the feel of the deck bucking under his boots, the sight of giant shell splashes towering over them, the sickening lurch when Hollister took that hit.

“But mostly,” he’d say, “it was a day when a bunch of ordinary sailors decided that running wasn’t enough. We weren’t supposed to win that one. By the math, by the book, we had no right to. And yet…”

He’d trail off, smile faintly.

“And yet those big battleships turned away,” he’d finish. “And our boys on the transports never saw them. That’s what I think about. Not the guns, not the explosions. Just the fact that somewhere, some kid from Kansas or New Jersey walked down a ramp onto a beach that should’ve been under battleship fire— and it wasn’t.”

Sometimes he’d be asked, “Would you do it again? Knowing what you know now?”

Jack would look down at his hands— older now, lined and scarred— and think of the names on that forecastle.

Then he’d lift his head, answer steady.

“I’d do my job again,” he’d say. “And on that day, my job was to point a little ship at something too big to make sense and keep going.”

Because that was what had happened off Samar. The destroyers and their crews had charged, not because they were fearless, but because fear had to get in line behind duty.

And in that narrow strip of ocean, for a few very long hours, that was enough.

News

THE NEWS THAT DETONATED ACROSS THE MEDIA WORLD

Two Rival Late-Night Legends Stun America by Secretly Launching an Unfiltered Independent News Channel — But Insider Leaks About the…

A PODCAST EPISODE NO ONE WAS READY FOR

A Celebrity Host Stuns a Political Power Couple Live On-Air — Refusing to Let Their “Mysterious, Too-Quiet Husband” Near His…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Announced a Secretive Independent Newsroom — But Their Tease of a Hidden…

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,” and Accidentally Exposed the Truth About Our Family in Front of Everyone

On My Wedding Day, My Stepmom Spilled Red Wine on My Dress, Laughed “Oops, Now You’re Not the Star Anymore,”…

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He Never Expected the Entire Reception to Hear My Response and Watch Our Family Finally Break Open”

“At My Sister’s Wedding, My Dad Sat Me With the Staff and Laughed ‘At Least You’re Good at Serving People’—He…

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting Match Broke Out, and the Truth About Their Relationship Forced Our Family to Choose Sides

At My Mom’s Funeral My Dad Introduced His “Assistant” as His New Fiancée — The Room Went Silent, a Shouting…

End of content

No more pages to load