How a Compact, Almost Forgotten Deck Gun Transformed America’s Modest PT Boats Into Nighttime Hunter-Killers—and Forced a Strategic Shift That Japan Could Never Counter Throughout the Turmoil of the Pacific War

Long before the world knew the full cost of the Pacific conflict, there existed a corner of naval warfare where improvisation, daring, and pure creativity reshaped the balance between giants and minnows. This story begins not with an admiral or a famous battleship, but with a collection of small, fast wooden boats—barely over 70 feet long—whose crews were asked to face ships ten times their size and a hundred times their firepower.

They were the U.S. Navy’s Patrol Torpedo boats—PT boats—nimble, loud, lightly armored, and typically under-gunned. And for a time, they struggled. Their torpedoes malfunctioned, their engines burned through fuel like bonfires dipped in gasoline, and their defensive weapons were designed more for chasing submarines or repelling aircraft than for taking on major surface vessels.

Yet, in the most unexpected way, a peculiar weapon—one dismissed as outdated, too bulky, or unsuitable—became the secret ingredient that made these fragile boats suddenly capable of damaging ships far larger than themselves. This “hidden gun,” as many later called it, didn’t look like much to outsiders. But for those who served on PT boats, it changed everything.

What follows is a journey from the inlets of the Solomons to the nighttime waves of New Britain, from the frustrations of failed torpedo runs to a moment when a well-placed burst of fire from an unlikely cannon helped turn the tide. It is a story of innovation born from necessity, of small crews who refused to accept the limits placed upon them, and of a weapon most people never realized played a pivotal role.

I. PT Boats: Fast, Brave, and Not Quite Ready

In 1942, when the first waves of PT boats reached the Pacific, Navy strategists envisioned them as swift assassins. They would race into enemy waters at high speed, launch torpedoes at large ships, and disappear before anyone could respond. Reality proved far messier.

The Mark 8 torpedoes they carried were temperamental. Many ran too deep. Others failed to detonate. Worse, their short range meant crews had to close in dangerously to launch them—a risky proposition when the target ship was armed with guns that could tear a PT boat apart in a single hit.

Crews began to improvise. They welded makeshift mounts for salvaged automatic guns. They rigged extra belts of ammunition along the deck. They experimented with ways to add punching power without sacrificing speed. But none of it provided the reliability or impact needed to stand toe-to-toe with larger warships.

That’s when the idea emerged—quietly at first—to repurpose an old piece of equipment. A weapon that had served faithfully in previous decades but had never been considered for small wooden torpedo boats. A weapon powerful enough to damage steel hulls and versatile enough to fire in rapid bursts.

It was the 37mm automatic cannon, originally fitted on early aircraft. And though it wasn’t new, it was about to reshape the future of PT warfare.

II. The Arrival of the Hidden Gun

Official Navy channels didn’t push the idea. In fact, much of the early movement came from the crews themselves. PT boat sailors were resourceful by necessity. When they saw a weapon that might help them stay alive and finish their missions, they pursued it relentlessly.

A few officers arranged for spare 37mm cannons to be delivered to their bases. Others bartered, negotiated, or simply took advantage of whatever equipment happened to fall off a supply ship. The installations were improvised at first—bolted onto the forward deck, often without specialized mounts. It wasn’t elegant, but it worked.

The 37mm cannon gave PT boats something they had desperately lacked:

Accurate medium-range fire

Penetrating power effective against thin hull plating

Rapid shots capable of disrupting enemy gunners

Crews quickly discovered that the new gun stabilized torpedo runs. By firing bursts before launching torpedoes, they could suppress return fire long enough to get into position safely.

More importantly, it offered a capability few expected: the chance to seriously damage larger vessels even without using torpedoes.

It wasn’t that PT boats suddenly became unstoppable. They were still vulnerable, still small, still operating against odds that seemed absurd. But their offensive potential soared.

Word spread. The 37mm gun became standard, then improved, then eventually replaced with an even more advanced version—often the 37mm M4 aircraft cannon originally carried by modified Airacobra fighters. What began as a field modification evolved into doctrine.

And before long, this modest cannon found its way into one of the most dramatic nighttime encounters of the Pacific campaign.

III. Night Hunters of the Solomons

By 1943, the Solomons were engulfed in a grinding struggle for control. The waters at night became a maze of patrols, supply runs, and ambushes. Japan relied heavily on swift destroyers to move troops and supplies under cover of darkness—a tactic the Allies called the “Tokyo Express.” These ships were tough, well-armed, and extremely difficult to stop.

PT boats, however, were perfectly suited to work in these cramped, dark waters. Their small size made them nearly invisible at night. Their engines, if throttled correctly, could blend into background noise. With the new deck gun, they could also harass and damage enemy ships in ways previously impossible.

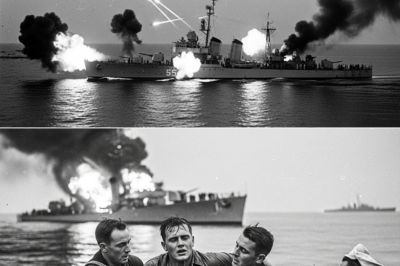

One such night in late 1943, a group of PT boats formed a barrier across a narrow channel used by Japanese forces. The moon hid behind clouds. Spray danced across the bow. Every sailor knew the stakes—a destroyer could obliterate a PT boat with a single accurate broadside.

Shortly after midnight, lookouts spotted the faint silhouette of a large vessel approaching at high speed.

The PT boats powered up.

Engines roared.

Orders snapped across the deck.

The first PT boat surged forward, closing to attack range. But instead of immediately launching torpedoes, the crew used their new secret weapon. The boat’s bow gunner squeezed the trigger, sending a disciplined burst of 37mm fire across the destroyer’s superstructure.

The effect was immediate.

Sparks flew. Enemy gunners ducked for cover. The destroyer hesitated just long enough for the PT boats to maneuver into a better firing position.

Moments later, torpedoes thundered into the water.

One struck home.

The destroyer shuddered, smoke billowed upward, and the ship staggered into an urgent retreat. The PTs peeled away into the darkness, surf spray hitting their faces, adrenaline pumping so hard that men later said they felt more awake than they had in days.

That night became one of several where PT boats, armed with the unexpected power of the hidden gun, disrupted or halted enemy operations. Word traveled rapidly through Japanese command channels: these American boats were no longer just nuisances. They could inflict real damage. Their attacks had to be taken seriously.

Japan’s destroyer groups altered routes. Escorts were assigned. Schedules changed. A sense of uncertainty began to creep into operations once considered routine.

All because tiny wooden boats had gained a sting far more potent than anyone predicted.

IV. Transforming the PT Boat Doctrine

As months progressed, the Navy officially embraced the modifications crews had pioneered. Specialized mounts were added. Improved cannons replaced the early ones. What began as a field improvisation became a recognized tactical innovation.

PT boats now used their deck guns to:

Target smaller supply craft with pinpoint accuracy

Disable steering and communications equipment on larger ships

Support ground forces near shorelines

Break up nighttime convoys before torpedoes were in range

In many engagements, the cannon became the primary weapon, with torpedoes reserved for when an enemy ship was fully exposed.

One veteran later remarked:

“We stopped feeling like mosquitoes and started feeling like wolves. Still small, still fast—but now we had teeth.”

The ripple effect was enormous. Japanese commanders began diverting more aircraft to patrol areas with PT activity. Smaller boats were reassigned to defensive duties. Destroyers expended more ammunition at night, firing into shadows for fear a PT boat lurked there.

Logistical pressure on Japan’s front lines intensified, and the long campaign across the Pacific gradually tilted further in the Allies’ favor.

V. Stories from the Deck

Behind every engagement was a human story.

There was the young gunner from Minnesota who’d never fired anything larger than a hunting rifle before joining a PT squadron. On his first night battle, he kept firing the 37mm so steadily and precisely that the crew credited him with preventing two direct hits from an enemy escort.

There was the engineer from Ohio who figured out how to stabilize the cannon’s improvised mount using nothing more than scrap metal, spare wire, and a section of broken railing. His fix became the blueprint for months.

There were the officers who risked reprimands by installing the guns before receiving formal authorization. They claimed later, half-jokingly, that paperwork was a luxury for ships made of steel, not wood.

And there were the crews who lived every day with the knowledge that their tiny vessels had no armor to speak of—that their survival depended on speed, teamwork, and a bit of daring.

The hidden gun gave them confidence. It gave them a chance.

And it earned them a place in naval history.

VI. A Legacy Carved Into the Waves

By the end of the Pacific conflict, PT boats had engaged in hundreds of missions. They delivered supplies, evacuated wounded personnel, escorted friendly vessels, and fought nighttime running battles with ships far larger than themselves. Many never returned. Others limped back with scars etched into their wooden hulls.

But their contribution was undeniable.

The addition of the 37mm cannon—humble, old, overlooked by many—played a crucial role in this transformation. It allowed PT boats to challenge destroyers and supply ships in ways no naval designer had expected. It forced a major power to alter its strategy. And it stands as a testament to the power of improvisation in the face of adversity.

Even today, preserved PT boats displayed in museums often feature this distinctive forward-deck cannon, a symbol of ingenuity and courage. Visitors who see it might assume it was standard, planned, or routine. In truth, it was innovation at its purest—born from necessity, refined through struggle, and perfected in the heat of battle.

A small weapon.

A small boat.

A massive impact.

For the men who served on PT boats, the hidden gun was more than metal and machinery. It was hope—hope that they could fight effectively, survive long enough to complete their mission, and return home.

And thanks to them, the story of how small vessels stood tall against overwhelming odds remains one of the most remarkable chapters in American naval history.

THE END

News

“How a Mysterious Invention Devoured 14,700 Tons of Silver Yet Sparked an Unforeseen Chain of Events That Forever Altered the Destiny of Empires, Explorers, and Ordinary Lives Across the World”

“How a Mysterious Invention Devoured 14,700 Tons of Silver Yet Sparked an Unforeseen Chain of Events That Forever Altered the…

She Sat in Silence for Years — and Then Dropped a Truth Bomb Live on Air. When This Sports Host Finally Spoke Up, the Studio Froze, the Network Panicked, and the League’s Carefully Guarded Secrets Started to Crack Open.

She Sat in Silence for Years — and Then Dropped a Truth Bomb Live on Air. When This Sports Host…

George Strait Walked Away From New York — and the City’s Concert Economy Instantly Hit Turbulence. Promoters Are Panicking, Economists Are Warning, and Fans Are Wondering How One Decision Shook an Entire Live-Music Capital.

George Strait Walked Away From New York — and the City’s Concert Economy Instantly Hit Turbulence. Promoters Are Panicking, Economists…

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Launch Bombshell Independent Newsroom: MSNBC and CBS Stars Ditch Corporate Chains for Raw Truth – Fans Erupt in Cheers as Media Moguls Panic Over ‘Collapse’ Threat

Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid Launch Bombshell Independent Newsroom: MSNBC and CBS Stars Ditch Corporate Chains for Raw…

How a Single Downed Airman in a Wide Blue Ocean Led an American Captain to Turn His Ship Toward Enemy Guns, Leaving the Watching Japanese Completely Astonished That Anyone Would Risk So Much for Just One Man

How a Single Downed Airman in a Wide Blue Ocean Led an American Captain to Turn His Ship Toward Enemy…

“The Top-Secret Sea-Hunting Rocket That ‘Saw’ in the Dark: How a Small Team of U.S. Engineers Built a Guided Weapon That Could Find Enemy Ships Without Radar—and Fought to Prove It Wasn’t Science Fiction.”

“The Top-Secret Sea-Hunting Rocket That ‘Saw’ in the Dark: How a Small Team of U.S. Engineers Built a Guided Weapon…

End of content

No more pages to load